User:Mdnavman/sandbox

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Vencedora |

| Namesake | Victoriou |

| Builder | Arsenal de Cartagana, Cartagena, Spain |

| Cost | 1,212,764.44 pesetas |

| Laid down | 1859 |

| Launched | 1861 |

| Commissioned | 1862 |

| Decommissioned | 1888 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Screw corvette |

| Displacement | 778 tonnes (766 long tons) |

| Length | 58 m (190 ft 3 in) |

| Installed power | 160 hp (119 kW) (nominal) |

| Propulsion |

|

| Sail plan | Schooner rig |

| Speed | 8 knots (15 km/h; 9.2 mph) |

| Complement | 98 to 130 |

| Armament |

|

Vencedora (English: Victorious) was a screw corvette of the Spanish Navy in commissioned from 1862 to 1888. She participated in the Chincha Islands War of 1865–1866, and in the Spanish-Moro conflict in the Philippines in the 1870s and 1880s.

Charcateristics

[edit]Vencedora was a Narváez-class screw corvette with a wooden hull and a schooner rig, and because of the latter she is listed in some sources as a schooner.[1] She had three masts and a bowsprit. She displaced 778 tons.[1] She was 58 metres (190 ft 3 in) long.[1] She had a La Maquinista Terrestre y Marítima steam engine manufactured in Barcelona, Spain, that was rated at a nominal 160 horsepower (119 kW) and could reach a maximum speed of 8 knots (15 km/h; 9.2 mph).[1] Her armament consisted of two 68-pounder (31 kg) 200-millimetre (7.9 in) smoothbore guns amidships and a 32-pounder (14.5 kg) 160-millimetre (6.3 in) smoothbore swivel gun on her bow.[1] She had a crew of 98 to 130 men.[1]

Construction and commissioning

[edit]Vencedora was laid down at the Arsenal de Cartagena in Cartagena, Spain, in 1859 as a wooden-hulled screw frigate with mixed sail and steam propulsion.[1] She was launched in 1861,[1] and after fitting out was commissioned in 1862.[1] Her total construction cost was 1,212,764.44 pesetas.[1]

Service history

[edit]Early service

[edit]Casto Méndez Núñez | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | July 1, 1824 Vigo, Spain |

| Died | August 21, 1869 (aged 45) Pontevedra, Spain |

| Buried | Panteón de Marinos Ilustres, Cádiz, Spain 36°28′47″N 006°11′37″W / 36.47972°N 6.19361°W |

| Allegiance | Kingdom of Spain |

| Service | Spanish Navy |

| Years of service | 1840–1869 |

| Rank | Cantralmirante (Counter admiral) |

| Commands |

|

| Battles / wars | |

| Alma mater | Nautical School, Vigo, Spain |

Casto Secundino María Méndez Núñez (1 July 1824 – 21 August 1869) was a Spanish Navy officer. He served in the First Italian War of Independence in Italy in 1849, the Spanish-Moro Conflict in the Philippines in 1861, and the Dominican Restoration War in the Caribbean in 1863–1864. He achieved international renown for his command of the Spanish Navy's Pacific Squadron during the Chincha Islands War in 1865–1866, becoming one of the major Spanish naval figures of the nineteenth century.

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Méndez Núñez was from Vigo, Spain, where he was born on 1 July 1824.[2] His father was a postal worker.[2] He completed his training at the Nautical School in Vigo. then went to Cádiz to take the naval entrance exams, which he passed.[3] He was granted the right to wear the uniform of a guardiamarina (midshipman) on 1 February 1839.[3]

Naval career

[edit]1840–1857

[edit]Méndez Núñez and he took up his post as a Spanish Navy midshipman on 24 March 1840 and remained at Cádiz until 4 September 1840, then reported aboard the 14-gun brig Nervión at Pasajes on 5 November 1840.[3] In 1842 he made a voyage to Fernando Po off the coast ofAfrica and distinguished himself so much by his superior performance that his eligibiity for promotion was accelerated by a year.[3] Operating along the coast of North Africa, he was promoted to guardiamarina de 1º (first midshipman) and reported aboard the paddle gunboat Isabel II.[3] In April 1846 he was commissioned as an officer after passing another exam, and on 11 July 1846 following he was promoted to the rank of alférez de navío (ship-of-the-line ensign), the lower of the Spanish Navy's two ensign ranks.[3]

Méndez Núñez reported to the new 12-gun brig Volador on 31 July 1846 and was named officer in command of the four midshipmen aboard.[3] Volador departed Cádiz on 10 October 1846 to deliver documents to Montevideo, Uruguay.[3] In March 1848 Volador headed for Rio de Janeiro and in June 1848 departed Rio de Janiero bound for Cádiz, which she reached on 1 August 1848.[3] On 7 January 1849 she put to sea from Barcelona to transport Spanish Army troops to Italy as part of an expedition to protect the Papal States[3] during the First Italian War of Independence.[3] Once the threat to the Papal States had abated, the expedition got back underway on 4 May 1849, participated in the capture of Terracina, then carried out maneuvers as a show of force at Naples, Gaeta, and Porto D'Auro which helped bring the war to an end.[3] On 18 May Méndez Núñez disembarked at Gaeta and on 29 May members of the Spanish expedition were reviewed by Pope Pius IX, showing him enemy flags they had captured, and he blessed the Spaniards and gave them thanks by Royal Order. Pius IX]] made Méndez Núñez and the other officers of the expedition the Commanders of the Cross of the Order of St. Gregory the Great.[3] Volador subsequently returned to Spain at Cádiz.[3]

Voladar arrived at Málaga in early 1850 and became part of the Training Squadron, subsequently cruising between Cape Rosas and Málaga.[3] By a Royal Order of 19 November 1950, Méndez Núñez received a promotion to teniente de navío (ship-of-the-line lieutenant.[3] He became commanding officer of the seven-gun schooner Cruz on 14 April 1851.[3] Under his command, Cruz patrolled the southern coast of Spain to prevent the smuggling of arms into the country.[3] Although Cruz was in need of repairs and scheduled for drydocking, Méndez Núñez received orders to carry documents to Havana in the Captaincy General of Cuba, and got underway from Cádiz on 8 February 1852.[3] Méndez Núñez displayed great seamanship in command during what turned out to be a risky and exhausting voyage, and Cruz avoided serious damage.[3]

In 1853, Méndez Núñez took command of the two-gun paddle gunboat Narváez, which still was under construction at the Reales Astilleros de Esteiro at Ferrol.[3] He received orders in January for Narvaez to proceed to Cádiz in January, but after she put to sea he found that she was unseaworthy due to her poor overall condition, including much rotten wood in her hull, forcing him to return to Ferrol, where Narvaez was scrapped.[3] He subsequently saw service with the Spanish coast guard.[3] Shore duty at the Ministry of the Navy followed, during which he translated into Spanish the 1820 book A Treatise on Naval Gunnery by the British Army officer Howard Douglas.[3][4][5] His translation was published in 1857.[3]

Philippines, 1858–1862

[edit]In 1858 Méndez Núñez became the commanding officer of another warship named Narváez, this one a screw corvette which, like the previous Narvaez, was under construction when he took command, also at the Reales Astilleros de Esteiro at Ferrol, and used the same steam engine that had been installed on the previous Narvaez.[3] Narvaez was commissioned on 20 November 1858.[6] She departed Cádiz on 10 February 1859, rounded the Cape of Good Hope, and headed for the Philippines in the Spanish East Indies, stopping along the coast of Luzon on 21 June before arriving at Manila on 26 June 1859, completing the passage in four months and eleven days.[3] On the Philippines station, Méndez Núñez took command of the paddle gunboat Jorge Juan, which off Basilan on 21 August 1860 sank five armed boats manned by Moro pirates from Jolo that were headed to the Visayas, took the survivors prisoner, and handed them over to Spanish authorities at Cavite.[3]

Méndez Núñez was promoted to capitán de fragata (frigate captain) on 3 May 1861 and given command of both the schooner Constancia and the Spanish naval division in the southern Philippine Islands. He raised his flag aboard Constancia.[3] His first operation after his promotion was against the Sultanate of Buayan, which was in rebellion against Spain.[3] The Sultan was based alongside the Rio Grande de Mindanao at Pagalungan on the southwestern coast of Mindanao in a well-garrisoned and well-equipped fort surrounded by a wall 7 metres (23 ft) high and 6 metres (20 ft) thick, surrounded by a 15-metre (49 ft) wide moat, and armed with short-range guns.[3] Arriving on the scene with his entire division — Constancia, the schooner Valiente, and the gunboats Arayat, Luzón, and Toal — Méndez Núñez disembarked a Spanish Army force to attack the fort on 16 November 1861, but the men sank up to their knees in the marshy ground around the fort, making an assault likely to result in high casualties, and he withdrew them.[3] At dawn on 17 November he launched a second attack, with the landing force supported by gunfire from Arayat and Pampanga, and the Spanish troops reached firmer ground, albeit at a greater distance from the fort, and managed emplace several artillery pieces ashore.[3] When that attack stalled, Méndez Núñez ordered small boats to reconnoitre the fort under enemy fire, then, having chosen a point of attack, maneuvered Constancia alongside the fort and sent an assault force into the fort as if boarding a ship.[3] The disembarked landing force renewed its attack at the same time, and two hours later the fort fell to the Spaniards withheavy casualties among its Moro defenders.[3] For this feat of arms, Méndez Núñez was promoted to capitán de navío (ship-of-the-line captain) in January 1862 and recalled to Spain. He arrived at Cádiz on 2 July 1862.[3]

Caribbean, 1862–1864

[edit]In October 1862, Méndez Núñez was ordered to command of the paddle gunboat Isabel II, on which he had once served, and he took command of her on 1 November 1862.[3] She dgot underway on 14 November and arrived at Havana on 8 December 1862.[3] From January to March 1863 Isabel II carried out patrols along the coast of Cuba to interdict the flow of arms and other contraband onto the island.[3] During political unrest in Venezuela, he left Havana on 23 May 1863 bound for Puerto Cabello and La Guaira. Upon arriving at Puerto Cabello, local authorities informed him that the port was blockaded, but Méndez Núñez took the position that no recognized government existed in Venezuela, and on that basis ignored the local authorities and entered the harbor, where Isabel II landed a [[Spanish Marine Infantry] force which protected all foreign diplomatic representatives, citizens, and property.[3] He personally negotiated an agreement under which no one opened fire. On 29 June 1863, he departed La Guaira to transport the chargé d'affaires of the United Kingdom and Spain and Venezuelan General José Antonio Páez to Puerto Cabello to sign the agreement, which took effect a few days later.[3] For engaging in diplomacy that prevented bloodshed and defused the crisis in Venezuela, he received the thanks of the Commander General of of Havana and the Government of Spain.[3]

After departing Venezuela, Méndez Núñez stopped at San Juan, Puerto Rico, and Santo Domingo, before arriving at Santiago de Cuba on the southeastern coast of Cuba, where Isabel II took on coal and dropped off a schooner captured in Santo Domingo.[3] Receiving word that the Dominican Restoration War had broken out on Santo Domingo, he brought 650 Spanish Army troops, a battery of horse artillery, mules, and 19 horses, and put to sea.[3] Isabel II arrived at Puerto Plata on the moonless evening of 27 August 1863, where a maritime pilot informed him that 200 Spaniards were holding out in a fort under siege by 2,000 rebels who planned to attack at dawn.[3] Isabel II picked her way through uncharted shallows, anchored at 22:00, and completed disembarkation of the troops at 01:30 on 28 August.[3] The Spaniards attacked the rebels at 02:00, taking them completely by surprise and quickly scattering them, relieving the fort.[3]

On 1 January 1864, Méndez Núñez returned to Havana, where Isabel II was scheduled to undergo an overhaul.[3] Leaving Isabel II, he took command of the screw frigate Princesa de Asturias on 22 January 1864[7]and returned to action off Santo Domingo aboard her, establishing a blockade of Manzanillo and Monte Chisti. He returned to Havana on 9 August 1864.[3]

Mendez Nuñez at anchor

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Méndez Núñez |

| Namesake | Admiral Casto Méndez Núñez |

| Builder | Reales Astilleros de Esteiro, Ferrol, Spain |

| Laid down | 22 September 1859 as frigate Resolución |

| Launched | 19 September 1861 |

| Completed | 28 August 1862 |

| Recommissioned | February 1870 |

| Renamed | Méndez Núñez, 21 August 1870 |

| Refit | 1867–1870 |

| Stricken | 1886 |

| Fate | Scrapped, 1896 |

| General characteristics (as reconstructed) | |

| Type | Central-battery ironclad |

| Displacement | 3,382 long tons (3,436 t) |

| Length | 236 ft 2 in (71.98 m) |

| Beam | 49 ft 3 in (15.01 m) |

| Draft | 21 ft 11 in (6.7 m) |

| Installed power | |

| Propulsion | 1 shaft, compound-expansion steam engine |

| Sail plan | Ship rig |

| Speed | about 8 knots (15 km/h; 9.2 mph) |

| Complement | 417 |

| Armament |

|

| Armor | |

The Spanish ironclad Méndez Núñez was a wooden-hulled armored corvette converted from the 38-gun, steam-powered frigate Resolución during the 1860s after the ship was badly damaged during the Chincha Islands War of 1864–1866. She was captured by rebels during the Cantonal Revolution in 1873 and participated in the Battle of Portmán that year before she was returned to government control after Cartagena surrendered in early 1874. The ship was stricken from the Navy List in 1886 and broken up ten years later.

Resolución

[edit]Characteristics

[edit]Resolución was a Lealtad-class screw frigate with a wooden hull. She had three masts and a bowsprit. She displaced 3,200 tons.[8] She was 70 metres (229 ft 8 in) long, 14 metres (45 ft 11 in) in beam, 7.33 metres (24 ft 1 in) in depth, and 6.16 metres (20 ft 3 in) in draft.[8] She had a John Penn and Sons steam engine rated at a nominal 500 horsepower (373 kW)[8] that generated 1,900 indicated horsepower (1,417 kW), giving her a speed of 11 knots (20 km/h; 13 mph).[8] She could carry up to 350 tons of coal.[8] Her armament consisted of fifteen 68-pounder (31 kg) 200-millimetre (7.9 in) smoothbore guns and twenty-six 32-pounder (14.5 kg) 160-millimetre (6.3 in) guns as well as two 150-millimetre (5.9 in) howitzers for disembarkation and use in her boats.[8] She had a crew of 500 men.[8]

Construction and commissioning

[edit]Resolución′s construction was authorized on 14 September 1859.[8] Her keel was laid at the Reales Astilleros de Esteiro in Ferrol, Spain, on 22 September 1859.[8] She was launched on 19 September 1861[8] and commissioned on 28 April 1862.[8] Her construction cost was 3,661,741 pesetas.[8]

Service history

[edit]Resolución′s first assignment was to the Training Squadron, which was under the overall command of Contralmirante (Counter Admiral) Luis Hernández-Pinzón Álvarez.[8] The squadron was dissolved in June 1862, and Resolución and her sister ship Nuestra Señora del Triunfo were assigned to the Pacific Squadron.[8] The two screw frigates entered the Arsenal de La Carraca at San Fernando to fit out for their deployment to the southeastern Pacific Ocean.[8]

Resolución and Nuestra Señora del Triunfo departed Cádiz on 10 August 1862.[8][9] Under the command of Pinzón, who flew his flag aboard Resolución, the two ships had both the political-military task of demonstrating a Spanish presence in the Americas and a scientific research mission[8] and had three zoologists, a geologist, a botanist, an anthropologist, a taxidermist, and a photographer aboard. The two screw frigates stopped at the Canary Islands and Cape Verde and then crossed the Atlantic Ocean to Brazil before arriving at the Río de la Plata (River Plate), where they rendezvoused with the screw corvette Vencedora.[8]

The screw schooner Virgen de Covadonga soon joined the expedition at the Río de la Plata as well.[8] The four ships got underway from Montevideo on 10 January 1863[10] and proceeded down the coast of Patagonia, passed the Falkland Islands, rounded Cape Horn on 6 February 1863,[11] and entered the Pacific Ocean.[8] They then stopped at the Chiloé Archipelago off the coast of Chile before continuing their voyage up the coasts of South America and North America, stopping at several ports before calling at San Francisco, California,[8][12] in the United States from 9 October[8][13] to 1 November 1863. They then headed southward and arrived at Valparaíso, Chile, on 13 January 1864.[14]

At the time, Spain still had not yet recognized the independence of Chile and Peru from the Spanish Empire, and the presence of the Spanish warships on the Pacific coast of South America — especially in the aftermath of Spain's annexation of the First Dominican Republic in 1861 and Spanish involvement in a mulitnational intervention Mexico in 1861–1862 — raised suspicions n South America as to the intentions of the Spanish government.[12] In retaliation for various hostile actions against Spanish citizens and property in Peru, Pinzón's squadron seized the Chincha Islands from Peru on 14 April 1864[8][12] without authorization from the Spanish government, taking several Peruvians prisoner.[12] With tensions spiking between Spain and Peru, and Resolución and Nuestra Señora del Triunfo covered an operation in which many of the Spaniards in Peru embarked on the steamer Heredia at Callao and Virgen de Covadonga towed Heredia out of the harbor under the guns of Peruvian Navy warships that were ready to open fire.[8][12] Spain and Peru avoided war, but Pinzón resigned his command on 9 November 1864 because he felt that the Spanish government had not supported his actions, and Vicealmirante (Vice Admiral) José Manuel Pareja took charge of the Pacific Squadron.[8][12]

An accidental fire destroyed Nuestra Señora del Triunfo on 25 November 1864, but Pareja's squadron received reinforcements on 30 December 1864 when the screw frigates Berenguela, Reina Blanca, and Villa de Madrid joined it.[15] Tensions with Peru remained high, and a member of Resolución′s crew was killed while on leave at Callao.[8] Pareja attempted to settle affairs with Peru by signing the Vivanco–Pareja Treaty with a Peruvian government representative aboard Villa de Madrid (Pareja's flagship), but the Peruvian Congress viewed it as a humiliation and refused to ratify it, and the failed treaty instead sparked the outbreak of the Peruvian Civil War of 1865 in February 1865.

The ship played a major role in the Chincha Islands War. Resolución participated in various military operations such as the blockade of the Chilean coast (Action of 17 November 1865), the Bombardment of Valparaíso and the Battle of Callao.

Méndez Núñez

[edit]Reconstruction

[edit]Characteristics

[edit]Méndez Núñez was 236 feet 3 inches (72.0 m) long at the waterline, had a beam of 49 feet 4 inches (15.0 m) and a mean draft of 21 feet 11 inches (6.7 m). The ship displaced 3,382 long tons (3,436 t). She had a single compound-expansion steam engine that drove her propeller using steam provided by four boilers. The engine was designed to produce a total of 2,250 indicated horsepower (1,680 kW) which gave the ship a speed of 8 knots (15 km/h; 9.2 mph).[16] For long-distance travel, Méndez Núñez was fitted with three masts and ship rigged. She carried 400 long tons (410 t) of coal.[17]

The ship was armed with four Armstrong 9-inch (229 mm) and two 8-inch (203 mm) rifled muzzle-loading guns. The ship was a central-battery ironclad with the armament concentrated amidships. Her wrought-iron armor covered most of the ship's hull and was five inches (127 mm) thick.[18]

Service history

[edit]

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Lealtad |

| Namesake | Loyalty |

| Ordered | 19 September 1859 {authorized) |

| Builder | Reales Astilleros de Esteiro, Ferrol, Spain |

| Cost | 3,518,068 pesetas |

| Laid down | 1860 |

| Launched | 15 October 1860 |

| Commissioned | 6 September 1861 |

| Decommissioned | 1893 |

| Fate | Sold for scrapping 1897 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Screw frigate |

| Displacement | 3,200 t (3,100 long tons) |

| Length | 70 m (229 ft 8 in) |

| Beam | 14 m (45 ft 11 in) |

| Draft | 6.16 m (20 ft 3 in) |

| Depth | 7.33 m (24 ft 1 in) |

| Installed power | 500 hp (373 kW) (nominal) |

| Propulsion | One John Penn and Sons steam engine, one shaft; 500 tons coal |

| Speed | 9.5 to 11 knots (17.6 to 20.4 km/h; 10.9 to 12.7 mph) |

| Complement | 500 |

| Armament |

|

Lealtad (Loyalty) was the lead ship of the Spanish Navy′s Lealtad-class of screw frigates. Commissioned in 1861, she operated in the Caribbean during the Chincha Islands War of 1865–1866 and in Cuba during the Ten Years' War of 1868–1878. She was disarmed in 1883 and served thereafter as a training ship. She was decommissioned in 1893 and sold for scrapping in 1897.

Characteristics

[edit]Lealtad was a Lealtad-class frigate screw frigate with a wooden hull. She had three masts and a bowsprit. She displaced 3,200 tons.[19] She was 70 metres (229 ft 8 in) long, 14 metres (45 ft 11 in) in beam, 7.33 metres (24 ft 1 in) in depth, and 6.16 metres (20 ft 3 in) in draft.[19] She had a John Penn and Sons steam engine rated at a nominal 500 horsepower (373 kW)[19] that generated 1,900 indicated horsepower (1,417 kW), giving her a speed of 9.5 to 11 knots (17.6 to 20.4 km/h; 10.9 to 12.7 mph).[19] She could carry up to 550 tons of coal.[19] Sources disagree on her armament, one claiming it consisted of fourteen 68-pounder (31 kg) 200-millimetre (7.9 in) smoothbore guns and twenty-six 32-pounder (14.5 kg) 160-millimetre (6.3 in) guns as well as four smaller bronze guns for disembarkation and use in her boats,[19] while another asserts that she was armed with one 220-millimetre (8.7 in) swivel gun on her bow, twenty 68-pounder (31 kg) 200-millimetre (7.9 in) smoothbore guns, fourteen 32-pounder (14.5 kg) 160-millimetre (6.3 in) guns, and six guns — two 150-millimetre (5.9 in) howitzers, two 120-millimetre (4.7 in) rifled guns, and two short 80-millimetre (3.1 in) rifled guns — for use in her boats. She had a crew of 480 or 500 men,[19] according to different sources.

Construction and commissioning

[edit]Lealtad′s construction was authorized on 14 September 1859.[19] Her keel was laid at the Reales Astilleros de Esteiro in Ferrol, Spain, in 1860. She was launched on 15 October 1860[19] and commissioned on 6 September 1861.[19] Her construction cost was 3,518,068 pesetas.[19]

Service history

[edit]After commissioning, Lealtad deployed to the Caribbean with her base at Havana in the Captaincy General of Cuba.[19] A break in relations between Spain and Mexico occurred in 1861[20] when Spain insisted on the settlement of damage claims it had made. A Spanish squadron under the command of Joaquín Gutierrez de Rubalcava[19][20][21] which included Lealtad departed Havana to transport a landing force under the command of General Juan Prim[20] to Veracruz as part of a mulitnational intervention in Mexico. The ships and landing force seized Veracruz on 14 December 1861,[22][23] and French and British forces arrived in January 1862. Spanish and British forces withdrew from Mexico in April 1862 when it became apparent that France intended to seize control of Mexico,[24] and Lealtad returned to Cuba.[20] She returned to Spain in August 1864, but when the Spanish government learned that France intended to make Maximilian I emperor of Mexico, she received orders to return to Cuba.

During the Chincha Islands War of 1865–1866, Lealtad and the screw frigate Nuestra Señora del Carmén operated in the Caribbean.[19] Lealtad returned to Spain in 1868 and was at Cádiz in September 1868 when Queen Isabella II was deposed in the Glorious Revolution.[19] The Ten Years' War broke out in Cuba in 1868, and in 1869 Lealtad once again deployed there[19] to support Spanish Empire forces fighting against insurgents of the Cuban Liberation Army. Her armament underwent alterations in 1870, leaving her with one 200-millimetre (7.9 in) smoothbore gun on her bow and twenty 68-pounder (31 kg) 200-millimetre (7.9 in) smoothbore guns and fourteen 32-pounder (14.5 kg) 160-millimetre (6.3 in) guns in her battery.[19]

Lealtad returned to Spain in 1882 and was assigned to the Training Squadron under the overall command of Contralmirante (Counter Admiral) Luis Bula y Vázquez.[19] She became a training ship for midshipmen in February 1883, with her armament becoming twenty-four 200-millimetre (7.9 in) smoothbore guns, two Hontoria 90-millimetre (3.5 in) guns, two Hontoria 70-millimetre (2.8 in) guns, and two machine guns.[19] She made a training cruise to the United Kingdom in April and May 1883 in which she visited Southampton and Portsmouth.[19]

Tasked with transporting the remains of Admiral Casto Méndez Núñez from Ferrol to Cádiz, Lealtad anchored at Vigo on 4 June 1883.[19] There she embarked Méndez Núñez′s remains, joined by a British Royal Navy squadron under the command of Vice-Admiral William Dowell and Rear-Admiral John Wilson consisting of the ironclad armoured frigates HMS Achilles, HMS Agincourt, HMS Minotaur, and HMS Northumberland, the centre battery ironclad HMS Sultan, and the ironclad turret ship HMS Neptune.[19] She disembarked Méndez Núñez′s remains at San Fernando at 08:30 on 16 June 1883, and Méndez Núñez was reburied at the Panteón de Marinos Ilustres (Pantheon of Illustrious Sailors) at Cádiz.[19]

In 1883, she also joined Carmén (the former Nuestra Señora del Carmén) and the armoured frigates Numancia and Vitoria escorted the Imperial German Navy screw corvette SMS Prinz Adalbert as Prinz Adalbert transported the German Crown Prince Frederick on his trip to Valencia.[19] In the summer of 1884, Lealtad was part of a Training Squadron commanded by Contralmirante (Counter Admiral) Francisco de Paula Llanos y Herrera.[25] King Alfonso XII and Queen Maria Christina embarked on Vitoria on 19 August 1884 for a voyage to La Coruña and Ferrol escorted by Numancia, Carmén, Lealtad, and the gunboat Paz.[25] The unprotected cruiser Navarra joined the squadron at Ferrol, they continued the journey along the coast of Spain until Alfonso XII and Maria Christina disembarked at Vigo on 25 August 1884.[25]

At the beginning of 1885, the screw frigate Gerona replaced Lealtad as the midshipmen training ship. During tensions with the German Empire over the status of the Caroline Islands in the Spanish East Indies, the Training Squadron — made up of Lealtad, Numancia, and Vitoria — anchored at Mahón on Menorca in the Balearic Islands on 18 March 1886 with orders to prepare to deploy to the Pacific Ocean to defend the Carolines.[19] Shortly afterwards, Navarra and the screw frigate Almansa joined them, and on 24 October the Ministry of the Navy ordered additional ships to the reinforce the squadron out of a fear that Germany would attack the Balearic Islands and use them as bargaining chips in peace talks after a possible war.[19] In the end, no conflict broke out between the countries.

In 1890, Lealtad was awaiting careening.[19] She was decommissioned in 1893[19] and thereafter was hulked at Cartagena to serve as a veterans' asylum until she was sold for scrapping in 1897.[19]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Vencedora (1862)". todoavante.es (in Spanish). 11 April 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2025.

- ^ a b González, Agustín Ramón Rodríguez (2024), Harding, Richard; Guimerá, Agustín (eds.), "Casto Méndez Núñez: The Admiral who could have been Regent, 1861–1868", Sailors, Statesmen and the Implementation of Naval Strategy, Boydell and Brewer, pp. 104–119, doi:10.1017/9781805431343.007, ISBN 978-1-80543-134-3

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw "Mendez Nunez, Casto Biografia". todoavante.es (in Spanish). 26 December 2023. Retrieved 9 February 2025.

- ^ Howard, Douglas (1855). A Treatise on Naval Gunnery (fourth ed.). London: John Murray, Ablemarle Street. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- ^ Howard, Douglas (1855). A Treatise on Naval Gunnery (fourth ed.). London: John Murray, Ablemarle Street. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- ^ "Narvaez (1857)". todoavante.es (in Spanish). 7 April 2022. Retrieved 9 February 2025.

- ^ "Princesa de Asturias (1859)". todoavante.es (in Spanish). 11 April 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z "Resolucion (1862)". todoavante.es (in Spanish). 9 April 2023. Retrieved 7 February 2025.

- ^ Almagro, p. 8.

- ^ Almagro, p. 34.

- ^ Almagro, p. 35.

- ^ a b c d e f Cite error: The named reference

todoavantetriunfo1862was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Almagro, p. 70.

- ^ Almagro, p. 72.

- ^ "Blanca (1859)". todoavante.es (in Spanish). 11 April 2022. Retrieved 21 December 2024.

- ^ Silverstone, p. 388

- ^ "Spanish Ironclads Tetuan, Mendes Nunes and Arapiles", p. 408

- ^ Gardiner, p. 381

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac "Lealtad (1861)". todoavante.es (in Spanish). 20 October 2023. Retrieved 6 February 2025.

- ^ a b c d "Princesa de Asturias (1859)". todoavante.es (in Spanish). 11 April 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2025.

- ^ de las Torres, p. 14.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

todoavanteconcepcion1861was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Bancroft (1888), p. 29

- ^ Bancroft (1888), p. 35

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

todoavanteNumancia1864was invoked but never defined (see the help page).

Bibliography

[edit]- Anca Alamillo, Alejandro (2009). Buques de la Armada Española del Siglo XIX (in Spanish). Ministry of Defence. ISBN 9788497815284.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888). History of Mexico VI: 1861–1887. New York: The Bancroft Company.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe. History of Mexico: Being a Popular History of the Mexican People from the Earliest Primitive Civilization to the Present Time The Bancroft Company, New York, 1914, pp. 466–506

- Blanco Núñez, José María (2011). La construcción naval en Ferrol, 1726-2011 (in Spanish). Navantia S.A.

- Bordejé y Morencos, Fernando de (1995). Crónica de la Marina española en el siglo XIX, 1868-1898 (in Spanish). Vol. II. Madrid: Ministry of Defence.

- González, Marcelino (2009). 50 Barcos españoles (in Spanish). Vol. II. Gijón, Spain: Fundación Alvargonzález.

- González-Llanos Galvache, Santiago (November 1996). La construcción naval en Ferrol durante el siglo XIX. Cuaderno monográfico nº 29 (in Spanish). Madrid: Instituto de Historia y Cultura Naval.

- Cortes constituyentes (1869). Diario de sesiones de las Córtes Constituyentes de la República (in Spanish). Vol. 1.

- Lledó Calabuig, José (1998). Buques de vapor de la armada española, del vapor de ruedas a la fragata acorazada, 1834-1885 (PDF) (in Spanish). Agualarga Editores.

- Rodríguez González, Agustín Ramón (1999). La Armada española, la campaña del Pacífico, 1862-1871. España frente a Chile y Perú (in Spanish). Madrid: Aqualarga Editores.

- Rodríguez González, Agustín Ramón; Coello Lillo, José Luis (2003). La fragata en la Armada española. 500 años de historia (in Spanish). IZAR. Construcciones Navales, S.A.

- Rubio, Carlos (1869). Historia filosófica de la revolución española de 1868. Vol. 2. Madrid: Miguel Guijarro.

- Torres, Martín de las (1867). El Archiduque Maximiliano de Austria en Méjico (in Spanish).

- VV.AA (1999). El Buque en la Armada española (in Spanish). Madrid: Editorial Sílex.

Velasco, probably in 1926.

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Velasco |

| Namesake | Luis Vicente de Velasco (1711–1762), Spanish naval commander |

| Operator | Spanish Navy |

| Ordered | 1915 |

| Builder | Sociedad Española de Construcción Naval (SECN), Cartagena Spain |

| Laid down | 6 July 1920 |

| Launched | 16 June 1923 |

| Commissioned | 27 December 1924 |

| Decommissioned | 9 April 1957 |

| Honors and awards | |

| Fate | Scrapped |

| Notes |

|

| General characteristics [1] | |

| Class and type | Alsedo-class destroyer |

| Displacement | |

| Length | |

| Beam | 8.23 m (27 ft) |

| Draught | 4.57 m (15 ft) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | 2 shafts; 2 geared steam turbines |

| Speed | 34 knots (63 km/h; 39 mph) |

| Range | 2,500 nmi (4,630 km; 2,877 mi) at 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph) |

| Complement | 86 |

| Armament |

|

Velasco was a Spanish Navy destroyer in commission from 1924 to 1957. She served in the Rif War in 1925 and fought on the Nationalist side during the Spanish Civil War of 1936–1939. While in commission, she served the Kingdom of Spain from 1924 to 1931, the Second Spanish Republic from 1931 to 1936, and the Nationalist faction and the Spanish State its victory established from 1936 to 1957.

Design and characteristics

[edit]The Alsedo class were designed jointly by the British companies Vickers and John Brown & Co..[2]|group=lower-alpha}} The Alsedo class was of similar layout to the Hawthorn Leslie variant of the British M-class destroyer.[3][4]

The ships were 86.25 metres (283 ft) long overall and 83.82 metres (275 ft), with a beam of 8.23 metres (27 ft) and a draught of 4.57 metres (15 ft). Displacement was 1,060 tonnes (1,043 long tons) standard and 1,336 tonnes (1,315 long tons) full load.[4] They were propelled by two geared steam turbines driving two shafts and fed by four Yarrow boilers and had a distinctive four-funneled silhouette. The ships a design speed of 34 knots (63 km/h; 39 mph). They were the first Spanish Navy ships to use only fuel oiil and could carry 276 tonnes (272 long tons) of oil, giving them a range of 1,500 nautical miles (2,800 km; 1,700 mi) at 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph). The ships had a crew of 86.[4]

The Alesdo-class ships were armed with three Vickers 4-inch (102 mm) guns manufactured under license in Spain and mounted in three single mounts, with one forward, one aft, and one between the second and third funnels, as well as two anti-aircraft guns,[4] identified by different sources as either 47-millimetre[4] or 2-pounder (40 mm) guns.[5][6] The anti-aircraft guns later were replaced by four 20 mm autocannons.[4][5] Four 533-millimetre (21 in) torpedo tubes were mounted in twin banks, and the Alsedo class ships were the first Spanish destroyers to carry torpedoes of that size.[4] The ships were fitted with two depth charge throwers sometime around 1945.[5] A rangefinder was mounted on each ship's bridge.[7]

By the time the Alsedo class entered service in the mid-1920s, destroyer design had advanced and made them obsolete. The Spanish Navy therefore cancelled plans to build three more ships of the class and instead next constructed the more modern and much larger Churruca-class destroyers.[4] Nonetheless, the Alsedo class had active and lengthy careers.[8]

Construction and commissioning

[edit]The Spanish Cortes (Parliament) passed a navy law on 17 February 1915 authorizing a large program of construction for the Spanish Navy, including three Alsedo-class destroyers to be built in Spain at the Sociedad Española de Construcción Naval (SECN) shipyard at Cartagena.[1][2] SECN was part of the same British consortium that included the ship's designers, Vickers and John Brown & Co.[2]

World War I (1914–1918) caused shortages of materials and equipment sourced from the United Kingdom and delayed construction of the Alsedo class, and Velasco′s keel was not laid at the SECN shipyard until 6 July 1920.[8] She was launched on 16 June 1923 and delivered to the Spanish Navy on 27 December 1924.[8]

Service history

[edit]Kingdom of Spain

[edit]1924–1927

[edit]Velasco and the light cruiser Reina Victoria Eugenia visited Lisbon, Portugal, in January 1925 for the celebration of the fourth centenary of Vasco da Gama.[8] After refueling at Almería, Spain, on 19 March 1925, she proceeded to the coast of Africa. In mid-July 1925 she got underway from Ceuta on the coast of North Africa with her sister ship Alsedo and the light cruisers Blas de Lezo and Méndez Núñez bound for Ferrol on the coast of Galicia.[8] They then continued on to Santander, where King Alfonso XIII received them when they arrived on 27 July 1925.[8] With the two light cruisers and the Royal Family present, Velasco and Alsedo each received a battle ensign acquired by popular subscription in Santander on 3 August 1925.[8] On the afternoon of 19 August 1925, Velasco got underway from Santander to conduct engine tests with Alfonso XIII on board.[8] She anchored in the Bay of La Concha two hours later, hen returned to Santander the same day.[8]

Assigned to the Training Squadron along with Alsedo, Blas de Lezo, Méndez Núñez, and the battleships Alfonso XIII and Alfonso XIII,[8] Velasco deployed for service in the Rif War. She took part in the Alhucemas landing at Alhucemas in Spanish Morocco on 9 September 1925.[8] Velasco and Alsedo both suffered damage in a collision with the gunboat Cánovas del Castillo on 12 September.[8] Velasco put into port for repairs which were completed in six days, then returned to the area of operations off Spanish Morocco.[8]

On 25 February 1926, Velasco arrived at Barcelona.[8] All three Alsedo-class destroyers made several cruises during 1926 with students from the Escuela de Guerra Naval (Naval War College) aboard, calling at various ports in Italy in the Mediterranean Sea and Adriatic Sea, as well as Istanbul and other ports.[8] On 20 May 1926, she departed Cartagena with the Training Squadron for exercises in the Mediterranean off Mazarrón with Alfonso XIII, Jaime I, Blas de Lezo, Méndez Núñez, and her sister ship Lazaga.[8] After a new commanding officer reported aboard on 16 July 1926, Velasco, Alsedo, Lazaga, and the torpedo boats T-5, T-6, T-14, and T-19 left Mahón on Menorca in the Balearic Islands on 18 July to conduct maneuvers with naval aviation aircraft off Catalonia.[8]

On 20 June 1927, the three Alsedo-class destroyers got undderway from Cartagena to begin a training cruise in the Mediterranean Sea for Naval War College students that lasted almost a month.[8] They conducted tactical exercises with the torpedo boats T-4, T-5, T-15, and T-19, the submarine division based at Mahón, and seaplanes based at Barcelona.[8] After parting company with the torpedo boats, the three destroyers made foreign port visits at Palermo in Sicily, and Ajaccio in Sardinia.[8] They arrived at Patras, Greece, on 27 July 1927, where on 28 July they participated in a ceremony at the site of the 1571 Battle of Lepanto.[8] They next stopped at Piraeus, Greece, and transited the Turkish Straits into the Black Sea to call at Varna, Bulgaria,and Constanta, Romania.[8] They returned through the straits to the Aegean Sea to visit Rhodes in the Italian Dodecanese and called at Haifa in Mandatory Palestine, Crete, Malta, Tunis, Bizerte, and Algiers before returning to Cartagena on 18 September 1927.[8]

In May 1928, the three Alsedo-class destroyers departed Cartagena and called at Ceuta and Cádiz before arriving at Marín, where they conducted gunnery exercises.[8] They visited Portsmouth, England, from 1 to 8 August 1928 for Cowes Week.[8] They also visited other ports in France and the United Kingdom during a training cruise with Naval War College students aboard.[8] During October and November 1928, the three Alsedo-class destroyers were part of a squadron that also included Alfonso XIII, Jaime I, Blas de Lezo, Méndez Núñez, the light cruiser Almirante Cervera, the destroyer Sánchez Barcáiztegui, the submarines Isaac Peral, B-1, B-2, B-3, B-4, B-5, B-6, C-1, and C-2, the torpedo boats T-11, T-13, T-14, T-15, T-18, and T-22, the seaplane carrier Dédalo, and the tug Cíclope that conducted exercises in the Balearic Islands and off Spain's Mediterranean coast.[8] After their conclusion, the squadron made port at Barcelona on 10 and 11 November 1928.[8] The squadron began to disband and depart Barcelona on 20 November 1928.[8]

1929–1931

[edit]Blas de Lezo, Méndez Núñez, and the three Alsedo-class destroyers called at Cádiz on 5 March 1929, but soon put back to sea for exercises in the Cíes Islands off Galicia with Alfonso XIII, Jaime I, and Almirante Cervera. The three destroyers anchored at Vigo on the night of 4–5 April 1929 and reached Cádiz on 9 April.[8] As part of a destroyer squadron that also included Sánchez Barcáiztegui, they arrived at Barcelona on 18 May 1929 along with a number of other Spanish Navy ships — including Dédalo, two battleships, five cruisers, nine submarines, two torpedo boats, and other smaller and auxiliary vessels — for the opening of the 1929 Barcelona International Exposition on 19 May.[8] the four destroyers got underway from Barcelona at 16:30 on 25 May 1929 and proceeded to Cartagena.[8]

The four destroyers reached Ferrol to refuel on 19 June 1929, with plans to stay until 22 June before proceeding to Santander.[8] However, the Dornier Do J Wal flying boat of Ramón Franco crashed into the sea during an attempted transatlantic flight, and they were ordered to instead steam to the Azores to join the search for the plane and its crew.[8] They departed at the end of June.[8] The British Royal Navy aircraft carrier HMS Eagle rescued Franco and his crew, and the four destroyers returned to Ferrol during the first week of July 1929.[8] Leaving Ferrol early on the morning of 8 July, they reached Santander on the night of 9 July.[8] After Sánchez Barcáiztegui embarked Naval War College students, the four destroyers put to sea with a squadron of torpedo boats for exercises.[8]

The four destroyers were among Spanish Navy ships that began to arrive at Palma de Mallorca on Mallorca in the Balearic Islands on the afternoon of 26 September 1929 for maneuvers in the waters of the islands.[8] Almirante Cervera, Blas de Lezo, Méndez Núñez, the light cruiser Príncipe Alfonso, and the destroyer Almirante Ferrándiz also took part in the exercises, which concluded in early October 1929. The ships left Palma de Mallorca on 5 October 1929.[8]

While the rest of the ships proceeded to Valencia, Velasco, Alsedo, Lazaga, Sánchez Barcáiztegui, and the destroyer José Luis Díaz anchored at Barcelona on the evening of 6 October 1929.[8] King Alfonso XIII arrived at Barcelona the same evening and boarded the motor ship Infanta Isabel to inspect the squadron.[8] After the king's visit, the ships steamed southward to resume the maneuvers.[8] On 16 October, part of the squadron returned to Barcelona for a stay of about ten days to rest the crews, repair damage, and take on supplies.[8] First the destroyer Bustamante led the torpedo boats into the harbor; Velasco, Almirante Ferrándiz, Alsedo, José Luis Díez, Lazaga. and Sánchez Barcáiztegui, and the destroyer Cardaso followed, and then the two battleships, the four cruisers, the submarines, and other smaller vessels entered port.[8] After the Barcelona visit, the destroyer squadron proceeded to Cartagena along with several of the other ships, arriving in late October 1929.[8] After a new commanding officer reported aboard, Velasco got back underway and steamed to Galicia.[8]

During the second half of March 1930, Velasco, Alsedo, Almirante Ferrándiz José Luis Díez, Lázaga, and Sánchez Barcáiztegui departed Cartagena stopped at Cádiz, where on the morning of 28 March 1930 José Luis Díez was presented with a battle ensign at the Arsenal de La Carraca.[8] They then proceeded to Marín, where two battleships and two cruisers joined them.[8] The ships began gunnery exercises at the Janer training ground in April 1930.[8] Once the gunnery exercises ended, the squadron remained in Galician waters and carried out various maneuvers, most of them in the estuary at Pontevedra.[8] Upon their completion, the squadron returned to Ferrol on 30 June 1930. The destroyer squadron called at El Musel at Gijón for several days in August 1930, them steamed to Santander and Bilbao.[8]

On 27 September 1930, the three Alsedo-class destroyers assembled at Cádiz with Alfonso XIII, Jaime I, Almirante Cervera, Blas de Lezo, Méndez Núñez, Príncipe Alfonso, Reina Victoria Eugenia, Almirante Ferrándiz, José Luis Díez, and Sánchez Barcáiztegui to begin a Mediterranean training cruise.[8] The ships visited Almería and Cartagena before arriving at Alicante in mid-December 1930.[8] Leaving the battleships at Cartagena for boiler repairs, the other ships steamed to Ferrol in January 1931.[8]

Second Spanish Republic

[edit]1931–1932

[edit]After King Alonso XIII was deposed, the Second Spanish Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931. The three Alsedo-class destroyers got underway from Barcelona with José Luis Díez and Sánchez Barcáiztegui and called at Cádiz from 21 to 30 April.[8] On the evening of 27 May 1931, the battleships España (ex-Alfonso XIII, renamed by the new government) and Jaime I, the light cruisers Almirante Cervera, Miguel de Cervantes, Méndez Núñez, República (ex-Reina Victoria Eugenia, renamed by the new government), and a destroyer squadron composed of Velasco, Almirante Ferrándiz, Lazaga, Lepanto, and Sánchez Barcáiztegui arrived at Ferrol, where they took part along with the seaplne carrier Dédalo and a submarine division in a naval review in the presence of the Minister of the Navy, the captain general of the Maritime Department of the North, and the commander of the squadron.[8]

The destroyer squadron carried out several patrols in the Strait of Gibraltar, making a stop in Cádiz on 3 June 1931 at the end of a voyage from Ceuta.[8] On the evening of 8 June 1931, the three Alsedo-class destroyers left Cadiz in company with Almirante Ferrándiz, José Luis Díez, Lepanto, and Sánchez Barcáiztegui bound for the Mediterranean.[8] All seven destroyers arrived at Palma de Mallorca overnight on 14-15 July 1931 after a voyage from Barcelona.[8] A new commanding officer reported aboard Velasco in August 1931 and was replaced at the beginning of October. On 5 November 1931, Velasco departed Cádiz.[8]

In May 1932, the Undersecretary of the Navy ordered Velasco to get underway from Cartagena, proceed to Valencia, and place itself under the orders of the civil governor there.[8] On 21&bsp;May 1932, the Khalifa of Spanish Morocco and his entourage boarded Velasco at Ceuta for transportation to Seville.[8] After visiting several other Spanish cities, the Moroccans departed Cadiz aboard the Civil Guard vessel Xauen on 27 May 1932 and, after a final stop in Málaga, boarded Velasco on 2 June 1932 for transportation to Ceuta.[8]

After rejoining her destroyer squadron, Velasco got underway from Palma de Mallorca in company with José Luis Díez and Lazaga on the morning of 28 July 1932 and set ccourse for Tarragona for maneuvers with a submarine squadron.[8] On 19 August 1932 Velasco arrived at Cádiz for repairs. and after their completion got back underway on 1 September. In October 1932, a new commanding officer took command of Velasco.[8] In November 1932 a squadron of destroyers consisting of Velasco, Alsedo, José Luis Díez, Lazaga, Lepanto, and Sánchez Barcáiztegui, completed a voyage from Mahón, anchoring at Palma de Mallorca on the night of 23 November 1932.[8] On the morning of 24 November, José Luis Díez, and Sánchez Barcáiztegui left for Alicante, and the three Alsedo- class followed them on the 25 November.[8]

1933–1936

[edit]In a reorganization of its forces at the beginning of 1933, the Spanish Navy assigned the three Alsedo-class destroyers to a separate destroyer squadron of their own.[8] In company with José Luis Díez, Lepanto, Sánchez Barcáiztegui and the destroyers Alcalá Galiano (AG) and Churruca, the three Alsedo-class ships completed a voyage from Cartagena to Almería on 29 April 1933.[8] They departed for the coast of Spanish Morocco on 30 April, then got underway from Ceuta on 3 May 1933 to return to Spain. In July 1933, the three Alsedo-class destroyers were among ships that conducted general maneuvers in the waters of the Balearic Islands.[8]

At the beginning of 1934, Velasco became part off the 1st Destroyer Squadron, while Alsedo and Laaga joined the newly created torpedo training division based at Cartagena.[8] In mid-February 1934, Velasco steamed from Cartagena to Ceuta with the transport Almirante Lobo to join Spanish naval forces in North Africa.[8]

In April 1934, Velasco took part in Spanish Navy maneuvers began in the Balearic Islands. Velasco and Alsedo then began repairs, thus missing a naval review took place on 11 June 1934 at Alcudia in the Balearic Islands in the presence of the President of the Republic Niceto Alcalá Zamora, Minister of the Navy Juan José Rocha García, and other authorities after the maneuvers concluded. Velasco received a new commanding officer while under repair, and yet another on 26 November 1934.[8] After getting underway from Ceuta, she stopped at Vigo from 8 to 9 December 1934 before proceeding to Gijón.[8]

Velasco′s commanding officer died in an automobile accident in May 1935.[8] In mid-May 1935, Velasco, Alsedo, Almirante Cervera, Libertad (the former Principe Alfonso), and Miguel de Cervantes cofmpleted gunnery exercises at the Janer training ground and later steamed to the Mediterranean for maneuvers.[8]

Spanish Civil War

[edit]When the Spanish Civil War began in July 1936, Velasco was serving at the Gunnery School in Marín. She was the only destroyer to side with the Nationalist faction.[8] After undergoing repairs at Ferrol, she was extermely active, especially in the Cantabrian Sea, bombarding fuel depots in Bilbao, laying mines off various ports, and participating in a National blockade of Republican-controlled ports.[8] She was escorting the battleship España when España struck a mine and sank within sight of Santander on 30 April 1937.[8] Velasco entered the minefield and came alongside the sinking battleship, rescuing her entire crew except for three men killed in the mine explosion.[8] For their actions, Velasco′s commanding officer received the individual Cross of Naval Merit and her crew received a collective Military Medal.[8]

On September 3, 1936, it faced the Republican submarine C-2. On 19 September 1936, the ship went to Cabo Peñas to rescue the armed tug Galicia, attacked by the Republican submarine B-6, which sank due to the leak caused by the tug's shots. It fought with numerous armed fishing boats and captured several merchant ships.

Between June and August 1938, it was repaired in Ferrol, and rejoined the squadron on 3 September, under the command of Lieutenant Commander Ricardo Benito Perera. On this occasion, it began to operate in the Mediterranean on escort missions, mining, port bombardment and other services. It returned to Ferrol on 13 October 1938 to undergo further repairs, but did not perform any more services during the war.

The three Alsedo destroyers were modernised between 1940 and 1943. The bridge was raised, a tripod mast with a crow's nest was added on the bridge and a smoke-guiding visor on the forward chimney. The main artillery was updated and three 20 mm anti-aircraft machine guns and two depth charge launching mortars were added. It was redelivered on 11 December 1943 and placed under the command of Lieutenant Commander Federico Fernández de la Puente.

On the morning of 24 August 1948, the destroyers Velasco and Lazaga arrived at Panjón, near Vigo, with a brigade of midshipmen from the Military Naval School, and the destroyer Alsedo arrived at midday, with the Minister of the Navy on board, Admiral Regalado, to celebrate the patron saint of the Navy. It was under the command of Lieutenant Commander Miguel Domínguez Sotelo.

In the following years he continued to serve at the Naval Military School. His last commander was Lieutenant Commander Enrique Golmayo Cifuentes.

Decommissioned on April 9, 1957.

Honors and awards

[edit]Military Medal for actions of 30 April 1937[8]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Whitley 2000, p. 242.

- ^ a b c Gardiner and Gray 1985, p. 376.

- ^ Friedman 2009, pp. 135–136.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Whitley 2000, pp. 242–243.

- ^ a b c Gardiner and Gray, p. 380.

- ^ Parkes 1931, p. 424

- ^ Friedman 2009, p. 135.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce "Velasco (1924)". todoavante.es (in Spanish). 8 April 2022. Retrieved 16 January 2025.

Bibliography

[edit]- Diarios ABC, La Época, Heraldo de Madrid, La Libertad, El Sol, La Vanguardia, La Voz.

- Semanario Vida Marítima..

- Aguilera, Alfredo; Elías, Vicente (1980). Buques de guerra españoles, 1885-1971 (in Spanish). Madrid: Editorial San Martín.

- Beevor, Antony (1999). The Spanish Civil War. London: Cassell. ISBN 0-304-35281-0.

- Blackman, Raymond V. B., ed. (1960). Jane's Fighting Ships 1960–61. London: Sampson Low, Marston & Co Ltd.

- Blanco Núñez, José María (2011). La construcción naval en Ferrol (1726-2011) (in Spanish). Navantia, S.A.

- Cervera Pery, José (1988). La guerra naval española (1936-39) (in Spanish). Madrid: Editorial San Martín.

- Coello Lillo, Juan Luis (2000). Buques de la Armada española. Los años de la posguerra (in Spanish). Madrid: Aqualarga.

- Friedman, Norman (2009). British Destroyers: From Earliest Days to the Second World War. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-049-9.

- Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-245-5.

- Martín Tornero, Antonio (1991). "El desembarco de Alhucemas. Organización, ejecución y consecuencias". Revista de Historia Militar (in Spanish). Vol. XXV, no. 70. Servicio Histórico Militar.

- Parkes, Oscar (1973) [Originally published 1931 by Sampson Low, Marston & Co.: London]. Jane's Fighting Ships. Newton Abbot, UK: David & Charles (Publishers). ISBN 0-7153-5849-9.

- Rohwer, Jürgen; Hümmelchen, Gerhard (1992). Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945. London: Greenhill Books. ISBN 1-85367-117-7.

- Whitley, M. J. (2000). Destroyers of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia. London: Cassell. ISBN 1-85409-521-8.

Aftermath

[edit]

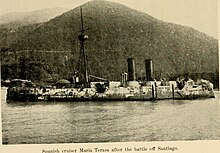

On 6 July 1898, the commander of the U.S. Navy's North Atlantic Squadron, Rear Admiral William T. Sampson, appointed a board chaired by Commodore John C. Watson to survey the damage to the Spanish ships lost in the Battle of Santiago de Cuba.[1] Watson's assistant Naval Constructor Richmond Pearson Hobson became supervisor of wrecks and convinced President William McKinley to support salvage operations in Cuba,[1] after which the U.S. Navy hired the Merritt & Chapman Derrick and Wrecking Company to do most of the salvage work.[1]

Surveys of the Spanish wrecks concluded that Infanta Maria Teresa was the least damaged of the Spanish ships sunk in the Battle of Santiago de Cuba[2] and the only one that could be salvaged.[1] She was pulled gently off the beach and refloated on 24 September 1898[2][1] and the tug {{|USS|Potomac|AT-50|6}} towed her to Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, for preliminary repairs.[2][1] With these completed, the U.S. Navy repair ship USS Vulcan and the civilian wrecking company vessel Merritt took Infanta Maria Teresa under tow and departed Guantánamo Bay on 29 October 1898 headed for Norfolk, Virginia, where permanent repairs could be made.[2][1] The three ships formed a tow stretching for nearly 1,000 yards (910 m), with Merritt leading and attached to Vulcan by a 400-yard (370 m) manila line and Vulcan in turn attached to Infanta Maria Teresa by a 460-yard (420 m) 15-inch (38 cm) manila chain.[1] Good weather allowed the ships to make 6 knots (6.9 mph; 11 km/h) as they headed eastward into the Windward Passage between Cuba and Haiti, with Infanta Maria Teresa assisting the tow by operating one of her steam engines.[1]

Good weather persisted on 30 October, and the ships rounded the northeastern tip of Cuba before 12:00 that day and headed toward the Bahamas. At around 20:00 that evening, however, the weather became unsettled, and it remained cloudy and squally on 31 October. On the morning of 1 November 1898, the three ships were in Crooked Island Passage in the Bahamas when a violent squall struck.[2][1] The weather continued to deteriorate in the hours that followed as a tropical storm passed through the area.[1] The tow's speed dropped to 2 knots (3.7 km/h; 2.3 mph), and Infanta Maria Teresa began to roll heavily and down by the bow, with the pumps unable to keep up with the ingress of water.

During the voyage, however, Vulcan and Infanta Maria Teresa encountered a violent storm on he morning of 1 November 1898; the tow cables broke, the repair ship Merritt took off her crew, and Infanta Maria Teresa was left adrift. , and Infanta María Teresa sank between two reefs off Cat Island in the Bahamas with a broken back, a total loss.[3]

Cervera decided to beach it about six miles west of Santiago de Cuba. Despite this, it was the one that received the least damage from the Spanish squadron, and the Americans decided to refloat it on September 24, being towed to Guantanamo for urgent repairs and to be able to tow it to the Norfolk base. A violent storm that occurred on November 1 broke the towing cables and the cruiser was left adrift. Several days later it was found stranded on Car Island, one of the keys of the Bahamas. This time, the damage was irreparable.

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Petronila |

| Namesake | Petronilla of Aragon (1136–1173) |

| Ordered | 8 August or 8 October 1853 (see text) |

| Builder | Arsenal de Cartagena, Cartagena, Spain |

| Cost | 2,909,640 pesetas |

| Laid down | 22 February 1854 |

| Launched | 27 February 1857 |

| Commissioned | February 1858 |

| Fate | Wrecked 8 August 1863 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Screw frigate |

| Displacement | 2,600 or 3,800 tonnes (2,600 or 3,700 long tons) |

| Length | 64 m (210 ft 0 in) |

| Beam | 13 m (42 ft 8 in) |

| Height | 7.22 m (23 ft 8 in) |

| Draft | 6.35 m (20 ft 10 in) |

| Installed power | 360 hp (268 kW) (nominal) |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 12 to 13 knots (22 to 24 km/h; 14 to 15 mph) |

| Complement | 390–400 |

| Armament |

|

Petronila was a screw frigate of the Spanish Navy commissioned in 1858. She was the first screw frigate ever built at the Arsenal de Cartagena. She took part in the multinational intervention in Mexico in 1861–1862 and was wrecked in 1863.

Petronila was named for Petronilla of Aragon (1136–1173),[4] sometimes spelled "Petronila" or "Petronella," who was Countess consort of Barcelona from 1150 to 1162, Countess of Barcelona from 1162 to 1164, and Queen Regent of Aragon from 1164 to 1173.

Construction and commissioning

[edit]Petronila′s construction was authorized along with that of her two sister ships, the screw frigates Berenguela and Reina Blanca, by a royal order of either 8 August[4] or 8 October[4][5] 1853 (according to different sources). She was laid down at the Arsenal de Cartagena in Cartagena, Spain, on 22 February 1854[5] as a wooden-hulled screw frigate with mixed sail and steam propulsion,[5] and was the first screw frigate built at the Arsenal de Cartagena.[6][7] She carried one of her 200-millimetre (7.9 in) guns on her bow and the rest in her battery;[5] one gun was rifled, the rest smoothbore.[6] She was launched on 27 February 1857,[5] and after fitting out she was commissioned in February 1858.[5] Her total construction cost was 2,909,640 pesetas.[5]

Service history

[edit]1858–1863

[edit]Under the command of Capitán de fragata (Frigate Captain) José María Beránger, Petronila embarked the King Consort, Francisco de Asís, Duke of Cádiz, at Alicante, Spain, at the end of May 1858 and transported him to Valencia, escorted by a squadron of Spanish Navy warships.[5] After the king consort returned to Cartagena aboard Petronila, the squadron was dissolved.[5] On 8 July 1858, Petronila got underway from Cartagena and, after calling at Cádiz, headed into the Cantabrian Sea for operations along the northern coast of Spain.[5] Subsequently, she was part of a squadron that escorted Queen Isabella II as she made a voyage aboard the ship-of-the-line Rey Don Francisco de Asís from Vigo to Ferrol, which the squadron reached on 1 September 1858.[5] On 5 September 1858, Isabella II boarded Petronila at Gijón in northwestern Spain for a voyage to Ferrol and then to La Coruña, where she disembarked.[5]

In 1859, Petronila embarked 346 marines of the Spanish Marine Infantry at Ferrol for transportation to Cadiz, but ran aground and to undergo repairs at a naval dockyard.[5] When she was assigned to the naval base at Havana in the Captaincy General of Cuba for duty with the Spanish Navy squadron in the Caribbean, she had to enter a commercial drydock for further repairs after she began to take on an excessive amount of water.[5]

From Havana, Petronila made several voyages, visiting New York City in the United States, Santo Domingo in the Captaincy General of Santo Domingo, Veracruz in Mexico, and La Guaira in Venezuela.[5] Under the command of Capitán de navío (Ship-of-the-Line Captain) Romualdo Martínez y Viñalet, she participated in a mulitnational intervention in Mexico to settle damage claims in 1861–1862 as part of a squadron under Joaquín Gutierrez de Rubalcava.[5][8] The Spanish ships seized Veracruz on 14 December 1861[9] and French and British forces arrived in January 1862. Spanish and British forces withdrew from Mexico in April 1862 when it became apparent that France intended to seize control of Mexico,[10] and Petronila embarked Spanish troops and returned to Cuba.[5]

Loss

[edit]On 2 August 1863, Petronila, still under Martínez′s command, got underway from Havana to make a month-long cruise along the northwestern coast of Cuba between Matanzas and Cape San Antonio.[5] On 8 August 1863, however, she ran hard aground at the entrance to the port of Mariel.[5][6][7] On the morning of 9 August, the gunboat Isabel la Católica, a sidewheel paddle steamer, departed Havana to assist Petronila, then returned to Havana to report what she had found.[5] On the afternoon of 9 August, Isabel la Católica returned with the gunboat Conde de Venadito to begin an effort to salvage Petronila, bringing divers and equipment such as pumps.[5]

Petronila was refloated on 17 August 1863, but her engines did not function and she remained aground.[5] On 21 August 1863 she was deemed lost, and salvage work shifted to the recovery of her guns, machinery, and other valuable equipment, which the corvette Niña transported to Havana.[5] Petronila′s machinery later was installed in the screw corvette Doña María de Molina, which was built at the Arsenal de La Carraca in San Fernando, Spain, between 1865 and 1869.[5]

In a court martial held on 7 December 1863, Martínez was acquitted of wrongdoing in the loss of Petronila.[7]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Cite error: The named reference

blowfeb2002was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e Cite error: The named reference

todoavanteinfantamariateresawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

spanamwar.comwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c Ministerio de Fomento. "Real Oreden mandando construir tres fragatas de guerra con máquinas de hélice". Boletín oficial del Ministerio de Fomento (in Spanish). p. 140.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x "Petronila (1858)". todoavante.es (in Spanish). 9 April 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2024.

- ^ a b c "La fragata Petronila" (PDF). La Ilustración Española y Americana (in Spanish).

- ^ a b c Fernández Duro, pp. 383-392.

- ^ de las Torres, p. 14.

- ^ Bancroft (1888), p. 29

- ^ Bancroft (1888), p. 35

Bibliography

[edit]| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Petronila |

| Namesake | Petronilla of Aragon (1136–1173) |

| Ordered | 8 August or 8 October 1853 (see text) |

| Builder | Arsenal de Cartagena, Cartagena, Spain |

| Cost | 2,909,640 pesetas |

| Laid down | 22 February 1854 |

| Launched | 27 February 1857 |

| Commissioned | February 1858 |

| Fate | Wrecked 8 August 1863 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Screw frigate |

| Displacement | 2,600 or 3,800 tonnes (2,600 or 3,700 long tons) |

| Length | 64 m (210 ft 0 in) |

| Beam | 13 m (42 ft 8 in) |

| Height | 7.22 m (23 ft 8 in) |

| Draft | 6.35 m (20 ft 10 in) |

| Installed power | 360 hp (268 kW) (nominal) |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 12 to 13 knots (22 to 24 km/h; 14 to 15 mph) |

| Complement | 390–400 |

| Armament |

|

Petronila was a screw frigate of the Spanish Navy commissioned in 1858. She was the first screw frigate ever built at the Arsenal de Cartagena. She took part in the multinational intervention in Mexico in 1861–1862 and was wrecked in 1863.

Petronila was named for Petronilla of Aragon (1136–1173),[1] sometimes spelled "Petronila" or "Petronella," who was Countess consort of Barcelona from 1150 to 1162, Countess of Barcelona from 1162 to 1164, and Queen Regent of Aragon from 1164 to 1173.

Construction and commissioning

[edit]Petronila′s construction was authorized along with that of her two sister ships, the screw frigates Berenguela and Reina Blanca, by a royal order of either 8 August[1] or 8 October[1][2] 1853 (according to different sources). She was laid down at the Arsenal de Cartagena in Cartagena, Spain, on 22 February 1854[2] as a wooden-hulled screw frigate with mixed sail and steam propulsion,[2] and was the first screw frigate built at the Arsenal de Cartagena.[3][4] She carried one of her 200-millimetre (7.9 in) guns on her bow and the rest in her battery;[2] one gun was rifled, the rest smoothbore.[3] She was launched on 27 February 1857,[2] and after fitting out she was commissioned in February 1858.[2] Her total construction cost was 2,909,640 pesetas.[2]

Service history

[edit]1858–1863

[edit]Under the command of Capitán de fragata (Frigate Captain) José María Beránger, Petronila embarked the King Consort, Francisco de Asís, Duke of Cádiz, at Alicante, Spain, at the end of May 1858 and transported him to Valencia, escorted by a squadron of Spanish Navy warships.[2] After the king consort returned to Cartagena aboard Petronila, the squadron was dissolved.[2] On 8 July 1858, Petronila got underway from Cartagena and, after calling at Cádiz, headed into the Cantabrian Sea for operations along the northern coast of Spain.[2] Subsequently, she was part of a squadron that escorted Queen Isabella II as she made a voyage aboard the ship-of-the-line Rey Don Francisco de Asís from Vigo to Ferrol, which the squadron reached on 1 September 1858.[2] On 5 September 1858, Isabella II boarded Petronila at Gijón in northwestern Spain for a voyage to Ferrol and then to La Coruña, where she disembarked.[2]

In 1859, Petronila embarked 346 marines of the Spanish Marine Infantry at Ferrol for transportation to Cadiz, but ran aground and to undergo repairs at a naval dockyard.[2] When she was assigned to the naval base at Havana in the Captaincy General of Cuba for duty with the Spanish Navy squadron in the Caribbean, she had to enter a commercial drydock for further repairs after she began to take on an excessive amount of water.[2]

From Havana, Petronila made several voyages, visiting New York City in the United States, Santo Domingo in the Captaincy General of Santo Domingo, Veracruz in Mexico, and La Guaira in Venezuela.[2] Under the command of Capitán de navío (Ship-of-the-Line Captain) Romualdo Martínez y Viñalet, she participated in a mulitnational intervention in Mexico to settle damage claims in 1861–1862 as part of a squadron under Joaquín Gutierrez de Rubalcava.[2][5] The Spanish ships seized Veracruz on 14 December 1861[6] and French and British forces arrived in January 1862. Spanish and British forces withdrew from Mexico in April 1862 when it became apparent that France intended to seize control of Mexico,[7] and Petronila embarked Spanish troops and returned to Cuba.[2]

Loss

[edit]On 2 August 1863, Petronila, still under Martínez′s command, got underway from Havana to make a month-long cruise along the northwestern coast of Cuba between Matanzas and Cape San Antonio.[2] On 8 August 1863, however, she ran hard aground at the entrance to the port of Mariel.[2][3][4] On the morning of 9 August, the gunboat Isabel la Católica, a sidewheel paddle steamer, departed Havana to assist Petronila, then returned to Havana to report what she had found.[2] On the afternoon of 9 August, Isabel la Católica returned with the gunboat Conde de Venadito to begin an effort to salvage Petronila, bringing divers and equipment such as pumps.[2]

Petronila was refloated on 17 August 1863, but her engines did not function and she remained aground.[2] On 21 August 1863 she was deemed lost, and salvage work shifted to the recovery of her guns, machinery, and other valuable equipment, which the corvette Niña transported to Havana.[2] Petronila′s machinery later was installed in the screw corvette Doña María de Molina, which was built at the Arsenal de La Carraca in San Fernando, Spain, between 1865 and 1869.[2]

In a court martial held on 7 December 1863, Martínez was acquitted of wrongdoing in the loss of Petronila.[4]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c Ministerio de Fomento. "Real Oreden mandando construir tres fragatas de guerra con máquinas de hélice". Boletín oficial del Ministerio de Fomento (in Spanish). p. 140.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x "Petronila (1858)". todoavante.es (in Spanish). 9 April 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2024.

- ^ a b c "La fragata Petronila" (PDF). La Ilustración Española y Americana (in Spanish).

- ^ a b c Fernández Duro, pp. 383-392.

- ^ de las Torres, p. 14.

- ^ Bancroft (1888), p. 29

- ^ Bancroft (1888), p. 35

Bibliography

[edit]- Bancroft, Hubert Howe. History of Mexico: Being a Popular History of the Mexican People from the Earliest Primitive Civilization to the Present Time The Bancroft Company, New York, 1914, pp. 466–506

- Fernández Duro, Cesareo (1867). Naufragios de la Armada Española (in Spanish). Madrid: Establecimiento tipográfico de los Señores Estrada Díaz y López.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe. History of Mexico: Being a Popular History of the Mexican People from the Earliest Primitive Civilization to the Present Time The Bancroft Company, New York, 1914, pp. 466–506

External links

[edit]- Todoavante Petronila (1858) (in Spanish)

External links

[edit]- Todoavante Petronila (1858) (in Spanish)

Berenguela transiting the Suez Canal in 1869.

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Berenguela |

| Namesake | Berengaria of Castile |

| Ordered | 8 or 9 October 1853 |

| Builder | Reales Astilleros de Esteiro, Ferrol, Spain |

| Cost | 3,082,909 pesetas |

| Laid down | 16 October 1854 or 4 April 1855 (see text) |

| Launched | 24 February 1857 |

| Commissioned | 1859 |

| Fate | Hulked 1875 |

| Decommissioned | 1877 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Screw frigate |

| Displacement | 2,600 or 3,800 tonnes (2,600 or 3,700 long tons) |

| Length | 64 m (210 ft 0 in) |

| Beam | 13 m (42 ft 8 in) |

| Height | 7.22 m (23 ft 8 in) |

| Draft | 6.35 m (20 ft 10 in) |

| Installed power | 360 hp (268 kW) (nominal) |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 8 knots (15 km/h; 9.2 mph) |

| Complement | 408 |

| Armament |

|

Berenguela (English: Berengaria) was a screw frigate of the Spanish Navy commissioned in 1857. She took part in the the mulitnational intervention in Mexico in 1861–1862, several actions during the Chincha Islands War of 1865–1866, and the Spanish-Moro conflict in the early 1870s and was the first Spanish Navy ship to transit the Suez Canal. She was disarmed in 1875 and decommissioned in 1877.

Berenguela was named for Berengaria of Castile (1179 or 1180–1246), who was Queen consort of León from 1197 to 1204 and Queen of Castile from June to August 1217.

Construction and commissioning

[edit]Berenguela′s construction was authorized along with that of the screw frigates Petronila and Reina Blanca by a royal order of either 8[1] or 9[2] October 1853 (sources disagree). She was laid down at the Reales Astilleros de Esteiro in Ferrol, Spain, on either 16 October 1854[3] or 4 April 1855[4] (sources disagree) as a wooden-hulled screw frigate with mixed sail and steam propulsion.[1] She was launched on 24 February 1857,[1] and after fitting out she was commissioned in September 1857.[1] Her total construction cost was 3,082,909 pesetas.[1]

Service history

[edit]Early service

[edit]After commissioning, Berenguela was assigned to service in the Caribbean, based at Havana in the Captaincy General of Cuba.[1] In mid-November 1860, she arrived at New York City, anchoring in New York Harbor off the The Battery in Manhattan.[5][6] After the United States Navy screw frigate USS Wabash was floated out of drydock at the New York Navy Yard in Brooklyn, New York, Berenguela entered the drydock for an overhaul of her machinery.[5] On the evening of 6 December 1860 two "medium-sized" shells lying on deck were ignited by sparks from a cigar and exploded.[7] Two sailors jumped or were blown overboard and landed in the drydock, suffering fatal injuries, and the explosion also injured four others.[7] A fire started, which the navy yard′s firefighters quickly extinguished.[7] Fortunately for Berenguela and her crew, two 80-pound (36 kg) shells lying near the explosion and fire did not themselves explode.[7]

Under the command of Capitán de navío (Ship-of-the-Line Captain) José Ignacio Rodríguez de Arias y Villavicencio, Berenguela took part in 1861 in a naval demonstration off Port-au-Prince, Haiti, by a squadron commanded by Joaquín Gutierrez de Rubalcava.[1] She then participated in a mulitnational intervention in Mexico to settle damage claims in 1861–1862, again as part of a squadron under Gutierrez de Rubalcava. The Spanish ships seized Veracruz on 14 December 1861[8] and French and British forces arrived in January 1862. Spanish and British forces withdrew from Mexico in 1862 when it became apparent that France intended to seize control of Mexico,[9] and Berenguela returned to Cuba.[1]

Chincha Islands War

[edit]Amid tensions between Spain, Chile, and Peru, Berenguela was reassigned to the Pacific Squadron in 1864. Getting underway from Havana under the command of Capitán de navío (Ship-of-the-Line Captain) Manuel de la Pezuela y Lobo,[1] she moved to Montevideo, Uruguay, where she and the screw frigate Reina Blanca rendezvoused with the screw frigate Villa de Madrid. The three ships passed through the Strait of Magellan into the Pacific Ocean and Berenguela reached Pisco, Peru, on 11 December 1864,[1] then joined the Pacific Squadron in the Chincha Islands on 30 December 1864.[1] Villa de Madrid became the flagship of the squadron's commander, Vicealmirante (Vice Admiral) José Manuel Pareja, whose predecessor Luis Hernández-Pinzón Álvarez had seized the Chincha Islands from Peru in April 1864. On 27 January 1865 Pareja and a Peruvian government representative, Manuel Ignacio de Vivanco, signed the Preliminary Treaty of Peace and Friendship between Spain and Peru, known informally as the Vivanco–Pareja Treaty, aboard Villa de Madrid in an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to settle claims between the two countries that instead sparked the outbreak of the Peruvian Civil War of 1865.

The political situation in the region further deteriorated during 1865 when Pareja steamed to Valparaíso, Chile, to settle Spanish claims.[10] When Chile refused to settle, Pareja announced a blockade of Chilean ports,[10] with Berenguela assigned to the blockade of Valparaíso. As a result of the blockade, the Chincha Islands War broke out between Spain and Chile on 24 September 1865. When the Chilean Navy corvettes Esmeralda and Maipú departed Valparaíso, Pareja reassigned Berenguela to join Reina Blanca in blockading Caldera.[1] While on blockade duty, Berenguela captured the steamer Matías Cousiño, which was making a voyage from Lota to Lota Alto, Chile, with a cargo of coal. On 27 November 1865, a group of Chilean gunboats attacked Berenguela off Caldera, and Berenguela drove off the attackers with gunfire. The blockade spread the Pacific Squadron thinly along the Chilean coast, and early setbacks in the war culminated in a humiliating Spanish naval defeat in the Battle of Papudo on 26 November 1865 in which Esmeralda captured the Spanish Navy schooner Virgen de Covadonga. News of the defeat prompted Pareja to commit suicide aboard Villa de Madrid off Valparaíso, shooting himself in his cabin on 28 November 1865 while lying on his bed wearing his dress uniform. He was buried at sea, and Capitán de navío (Ship-of-the-Line Captain) Casto Méndez Núñez received a promotion to contralmirante (counteradmiral) and took command of the Pacific Squadron.[11]