Palm Springs, California

Palm Springs | |

|---|---|

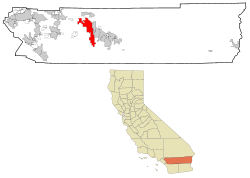

Location within Riverside County | |

| Coordinates: 33°49′49″N 116°32′43″W / 33.83028°N 116.54528°W[1] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Riverside |

| Native American Reservation (partial) | Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians |

| Incorporated | April 20, 1938[2] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager |

| • Mayor | Ron De Harte |

| • Mayor Pro Tem | Naomi Soto |

| • City Council | David Ready Grace Elena Garner Jeffrey Bernstein |

| • City Manager | Scott C. Stiles |

| • Assistant City Manager | Teresa Gallavan |

| Area | |

• Total | 94.68 sq mi (245.21 km2) |

| • Land | 94.54 sq mi (244.85 km2) |

| • Water | 0.14 sq mi (0.36 km2) 0.90% |

| Elevation | 479 ft (146 m) |

| Population | |

• Total | 44,575 |

| • Density | 513.21/sq mi (198.15/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 92262–92264 |

| Area codes | 442/760 |

| FIPS code | 06-55254 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 1652768, 2411357 |

| Website | palmspringsca |

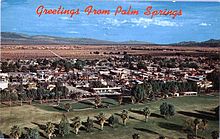

Palm Springs (Cahuilla: Séc-he)[5][6] is a desert resort city in Riverside County, California, United States, within the Colorado Desert's Coachella Valley. The city covers approximately 94 square miles (240 km2), making it the largest city in Riverside County by land area. With multiple plots in checkerboard pattern, more than 10% of the city is part of the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians reservation land and is the administrative capital of the most populated reservation in California.

The population of Palm Springs was 44,575 as of the 2020 census, but because Palm Springs is a retirement location and a winter snowbird destination, the city's population triples between November and March.[7]

The city is noted for its mid-century modern architecture, design elements, arts and cultural scene, and recreational activities.[8]

History

[edit]Founding

[edit]Pre-colonial history

[edit]The first humans to settle in the area were the Cahuilla people, who arrived 2,000 years ago.[9][10][11] Cahuilla Indians lived here in isolation from other cultures for hundreds of years prior to European contact.[12] They spoke Ivilyuat, which is a Uto-Aztecan language.[13]

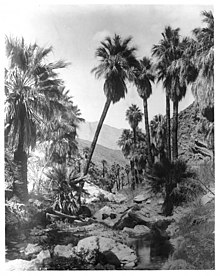

Numerous prominent and powerful Cahuilla leaders were from the area, including Cahuilla Lion (Chief Juan Antonio).[14] Palm Canyon was occupied during the winter months, but they often moved to cooler Chino Canyon during the summer months.[15]

The Cahuilla Indians had several permanent settlements in the canyons of Palm Springs due to the abundance of water and shade. Various hot springs were used during wintertime. The Cahuilla hunted rabbit, mountain goat, and quail while trapping fish in nearby lakes and rivers. While men were responsible for hunting, women were responsible for collecting berries, acorns, and seeds. They also made tortillas from mesquite seeds.[9] While the Cahuillas often spent the summers in Indian Canyons, the current site of the former Spa Resort Casino, in downtown, was often used during winter due to its natural hot springs.[10]

Native American petroglyphs can be seen in Tahquitz, Chino, and Indian Canyons. The Cahuilla's irrigation ditches, dams, and house pits can also be seen here.[16] Ancient petroglyphs, pictographs and mortar holes can be seen in Andreas Canyon. The mortar holes were used to grind acorns into meal.[17][18]

The Agua Caliente ("Hot Water") Reservation was established in 1876 and consists of 31,128 acres (12,597 ha). Six thousand seven hundred acres (2,700 ha) are located by Downtown Palm Springs.[19] The Native American land is on long lease land and next to one of California's high-end communities, making the tribe one of the wealthiest in California.[20]

The first name for Palm Springs was given by the native Cahuilla: "Se-Khi" (boiling water).[21][22] When the Agua Caliente Reservation was established by the United States government in 1876, the reservation land was composed of alternating sections (640 acres or 260 ha) of land laid out across the desert in a checkerboard pattern. The alternating non-reservation sections were granted to the Southern Pacific Railroad as an incentive to bring rail lines through the Sonoran Desert.

A number of streets and areas in Palm Springs are named for Native American notables, including Andreas, Arenas, Amado, Belardo, Lugo, Patencio, Saturnino, and Chino. All of these are common Cahuilla surnames.[10]

Presently the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians is composed of several smaller bands who live in the modern-day Coachella Valley and San Gorgonio Pass. The Agua Caliente Reservation occupies 32,000 acres (13,000 ha), of which 6,700 acres (2,700 ha) lie within the city limits, making the Agua Caliente natives the city's largest landowners. (Tribal enrollment as of 2010 was 410 people.[23])

Mexican explorers

[edit]

As of 1821 Mexico was independent of Spain, and in March 1823, the Mexican Monarchy ended. That same year (in December) Mexican diarist José María Estudillo and Brevet Captain José Romero were sent to find a route from Sonora to Alta California; on their expedition, they first recorded the existence of "Agua Caliente" at Palm Springs, California.[24][25]: 30 With the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo after the Mexican-American War, the region became part of the United States in 1848.

Later 19th century

[edit]Early names and European settlers

[edit]One possible origin of palm in the place name comes from early Spanish explorers who referred to the area as La Palma de la Mano de Dios or "The Palm of God's hand".[26] The earliest use of the name "Palm Springs" is from United States Topographical Engineers who used the term in 1853 maps.[27] According to William Bright, when the word "palm" appears in Californian place names, it usually refers to the native California fan palm, Washingtonia filifera, which is abundant in the Palm Springs area.[28] Other early names were "Palmetto Spring" and "Big Palm Springs".[29]

The first European resident in Palm Springs itself was Jack Summers, who ran the stagecoach station on the Bradshaw Trail in 1862.[30]: 44, 149 Fourteen years later (1876), the Southern Pacific railroad was laid 6 miles (9.5 km) to the north, isolating the station.[30]: 17 In 1880, local Indian Pedro Chino was selling parcels near the springs to William Van Slyke and Mathew Bryne in a series of questionable transactions; they in turn brought in W. R. Porter to help market their property through the "Palm City Land and Water Company".[25]: 275 By 1885, when San Francisco attorney (later known as "Judge") John Guthrie McCallum began buying property in Palm Springs, the name was already in wide acceptance. The area was named "Palm Valley" when McCallum incorporated the "Palm Valley Land and Water Company" with partners O.C. Miller, H.C. Campbell, and James Adams, M.D.[25]: 280 [31][32]

Land development and drought

[edit]

McCallum, who had brought his ill son to the dry climate for health, brought in irrigation advocate Dr. Oliver Wozencroft and engineer J. P. Lippincott to help construct a canal from the Whitewater River to fruit orchards on his property.[25]: 276–279 He also asked Dr. Welwood Murray to establish a hotel across the street from his residence. Murray did so in 1886 (he later became a famous horticulturalist).[25]: 280 The crops and irrigation systems suffered flooding in 1893 from record rainfall, and then an 11-year drought (1894–1905) caused further damage.[24]: 40

20th century

[edit]Resort development

[edit]

The city became a fashionable resort in the 1900s[33] when health tourists arrived with conditions that required dry heat. Because of the heat, however, the population dropped markedly in the summer months.[34] In 1906 naturalist and travel writer George Wharton James's two volume The Wonders of the Colorado Desert described Palm Springs as having "great charms and attractiveness"[35]: 278–281 and included an account of his stay at Murray's hotel.[36] As James also described, Palm Springs was more comfortable in its microclimate because the area was covered in the shadow of Mount San Jacinto to the west[31] and in the winter the mountains block cold winds from the San Gorgonio Pass.[37] Early illustrious visitors included John Muir and his daughters, U.S. Vice President Charles Fairbanks, and Fanny Stevenson, widow of Robert Louis Stevenson. Murray's hotel was closed in 1909 and torn down in 1954.[24]: 45

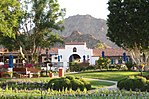

Nellie N. Coffman and her physician husband Harry established The Desert Inn as a hotel and sanitarium in 1909.[38][39] It was expanded as a modern hotel in 1927 and continued on until 1967.[24]: Ch. 13 [40][41] Coffman herself was a "driving force" in the city's tourism industry until her death in 1950.[42]

James's Wonders of the Colorado Desert (above) was followed in 1920 by J. Smeaton Chase's Our Araby: Palm Springs and the Garden of the Sun, which also promoted the area.[43] In 1924 Pearl McCallum (daughter of Judge McCallum) returned to Palm Springs and built the Oasis Hotel with her husband Austin G. McManus; the Modern/Art Deco resort was designed by Lloyd Wright and featured a 40-foot (12 m) tower.[24]: 68–69 [44]

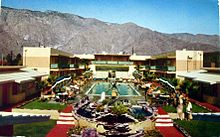

The next major hotel was the El Mirador, a large and luxurious resort that attracted the biggest movie stars; opening in 1927, its prominent feature was a 68-foot-tall (21 m) Renaissance style tower.[24]: Ch. 23 [45] Silent film star Fritzi Ridgeway's 100-room Hotel del Tahquitz was built in 1929, next to the "Fool's Folly" mansion built by Chicago heiress Lois Kellogg.[46] Golfing was available at the O'Donnell 9 hole course (1926) and the El Mirador (1929) course (see Golf below). Hollywood movie stars were attracted by the hot dry, sunny weather and seclusion—they built homes and estates in the Warm Sands, The Mesa, and Historic Tennis Club neighborhoods (see Neighborhoods below). About 20,000 visitors came to the area in 1922.[47]

Palm Springs became popular with movie stars in the 1930s[48] and estate building expanded into the Movie Colony neighborhoods, Tahquitz River Estates, and Las Palmas neighborhoods. Actors Charles Farrell and Ralph Bellamy opened the Racquet Club in 1934[24]: Ch. 25 [49][50] and Pearl McCallum opened the Tennis Club in 1937.[44] Nightclubs were set up as well, with Al Wertheimer opening The Dunes outside of Palm Springs in 1934[24]: 254 and the Chi Chi nightclub opening in 1936.[51][52]: 206–207 Besides the gambling available at the Dunes Club, other casinos included The 139 Club and The Cove Club outside of the city.[53][54]

Shopping district

[edit]

Bullock's, a large upscale department store on Broadway in Los Angeles, opened a Spanish Colonial-style "resort store" within the Desert Inn complex in 1930. When Bullock's opened a full department store at 151 Palm Canyon Drive in 1947, J. W. Robinson's, another large L.A. store, took the former Bullock's location and opened its own resort store there.[55]

Southern California's first self-contained shopping center was in Palm Springs, La Plaza (originally Palm Springs Plaza), and on-street, open air center anchored by a small Desmond's department store, in 1936. The three-level parking garage for 141 cars was an innovation and the largest in Riverside County at that time.[56] In the mid-twentieth century across the street on Palm Canyon Drive were department stores like Bullock's/Bullocks Wilshire (No. 151, 1947–1990), J. W. Robinson's (No. 333, 1958–1987),[57][58][59] and Saks Fifth Avenue (opened October 16, 1959, at No. 490),[60] forming a large shopping district. In 1967 the Desert Fashion Plaza mall was built, I. Magnin opened there (closed 1992)[61] and Saks closed its previous location and moved into a new larger store in the mall. Joseph Magnin Co. opened a 26,000-square-foot (2,400 m2) department store in the mall in 1969,[62] meaning that together with a Sears at 611 Palm Canyon Dr., for two decades, downtown boasted seven department stores, plus the Palm Springs Mall 1.5 miles (2.5 km) to the east operating from 1959 to 2005.

World War II

[edit]When the United States entered World War II, Palm Springs and the Coachella Valley were important in the war effort. The original airfield near Palm Springs became a staging area for the Air Corps Ferrying Command's 21st Ferrying Group in November 1941 and a new airfield was built 1⁄2 mile (0.8 km) from the old site. The new airfield,[63]: 43 designated Palm Springs Army Airfield,[64] was completed in early 1942. Personnel from the Air Transport Command 560th Army Air Forces Base Unit stayed at the La Paz Guest Ranch and training was conducted at the airfield by the 72nd and 73rd Ferrying Squadrons. Later training was provided by the IV Fighter Command 459th Base Headquarters and Air Base Squadron.

Eight months before Pearl Harbor Day, the El Mirador Hotel was fully booked and adding new facilities.[65] After the war started, the U.S. government bought the hotel from owner Warren Phinney for $750,000,[66] just over $13,000,000 if including inflation in 2020, and converted it into the Torney General Hospital,[67] with Italian prisoners of war serving as kitchen help and orderlies in 1944 and 1945.[68] Through the war it was staffed with 1,500 personnel and treated some 19,000 patients.[50]: 55

General Patton's Desert Training Center encompassed the entire region, with its headquarters in Camp Young at the Chiriaco Summit and an equipment depot maintained by the 66th Ordnance in present-day Palm Desert.[63]: 40

Post-World War II

[edit]

Architectural modernists flourished with commissions from the stars, using the city to explore architectural innovations, new artistic venues, and an exotic back-to-the-land experiences. Inventive architects designed unique vacation houses, such as steel houses with prefabricated panels and folding roofs, a glass-and-steel house in a boulder-strewn landscape, and a carousel house that turned to avoid the sun's glare.[69]

In 1946, Richard Neutra designed the Kaufmann Desert House. A modernist classic, this mostly glass residence incorporated the latest technological advances in building materials, using natural lighting and floating planes and flowing space for proportion and detail.[70] In recent years an energetic preservation program has protected and enhanced many classic buildings.

Culver (2010) argues that Palm Springs architecture became the model for mass-produced suburban housing, especially in the Southwest. This "Desert Modern" style was a high-end architectural style featuring open-design plans, wall-to-wall carpeting, air-conditioning, swimming pools, and very large windows. As Culver concludes, "While environmentalists might condemn desert modern, the masses would not. Here, it seemed, were houses that fully merged inside and outside, providing spaces for that essential component of Californian—and indeed middle-class American—life: leisure. While not everyone could have a Neutra masterpiece, many families could adopt aspects of Palm Springs modern."[71]

Hollywood values permeated the resort as it combined celebrity, health, new wealth, and sex. As Culver (2010) explains: "The bohemian sexual and marital mores already apparent in Hollywood intersected with the resort atmosphere of Palm Springs, and this new, more open sexuality would gradually appear elsewhere in national tourist culture."[71] During this period, the city government, stimulated by real estate developers, systematically removed and excluded poor people and Native Americans.[72][73]

Palm Springs was pictured by the French photographer Robert Doisneau in November 1960 as part of an assignment for Fortune[74] on the construction of golf courses in this particularly dry and hot area of the Colorado desert. Doisneau submitted around 300 slides following his ten-day stay depicting the lifestyle of wealthy retirees and Hollywood stars in the 1960s. At the time, Palm Springs counted just 19 courses, which had grown to 125 by 2010.[75]

Section 14 evictions

[edit]Section 14 is a square mile of land owned by the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians within close walking distance of downtown. Former residents in this area, mostly black people and other people of color, lived in land leased in short terms by individual Indigenous owners. Commercial development did not occur due to the 10 year limit on the leases.[76] After changes in the Indian Leasing Act in 1959, long term leases were permitted. Mayor Frank Bogert and other city officials advocated to the conservators that managed the tribe's leases to end the short-term leases and enter into long-term leases to largely white property owners for redevelopment. City funds were used to clear the land for redevelopment, including burning "shacks and makeshift homes... [which had] rented for $20 to $40 a month."[77] In 2021 the California Attorney General's office later called the displacement a "city-engineered holocaust", depriving dozens of Black and Latino people of generational wealth.[78]

After existing non-Indian residents were evicted in the 1960s, the tribe built the Spa Hotel and Casino downtown and the city built the Palm Springs Convention Center; also, the tribe leased land for developers to build hotels and condos.[79] The tribe had collaborated with the city in evicting the residents and destroying the structures, with tribal allottees and conservators signing burn permits and Tribal Chair Edmund Siva sending a letter to the Palm Springs City Council thanking it for its "clean-up campaign."[80]

The Palm Springs Human Relations Commission cited this history, as well as a conflict of interest while Bogert acted as conservator for tribal land which was being demolished by the city, and racist comments regarding the "poor Blacks" who lived in Section 14, as justification for removing a statue of Bogert on horseback placed in 1990 in front of the Palm Springs City Hall.[81] The City Council of Palm Springs ordered its removal in 2021 and formally apologized for the eviction of the Section 14 residents.[82] After legal objections to its removal from Bogert's supporters and family members were rejected by the courts, the statue was relocated on July 13, 2022.[83] Section 14 residents are still seeking financial reparations for the evictions.[84]

Year-round living

[edit]

Similar to the pre-war era, Palm Springs remained popular with the rich and famous of Hollywood, as well as retirees and Canadian tourists.[85] Between 1947 and 1965, the Alexander Construction Company built some 2,200 houses in Palm Springs effectively doubling its housing capacity.

As the 1970s drew to a close, increasing numbers of retirees moved to the Coachella Valley. As a result, Palm Springs began to evolve from a virtual ghost town in the summer to a year-round community. Businesses and hotels that used to close for the months of July and August instead remained open all summer. As commerce grew, so too did the number of families with children.

The recession of 1973–1975 affected Palm Springs as many of the wealthy residents had to cut back on their spending.[86] Later in the 1970s numerous Chicago mobsters invested $50 million in the Palm Springs area, buying houses, land, and businesses.[87] While Palm Springs faced competition from the desert cities to the east in the later 1980s,[88] it has continued to prosper into the 21st century.[89]

Palm Springs (as well as surrounding areas) became a desired destination as the COVID-19 pandemic began; the city saw an increase of residents from larger cities like Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Seattle, with new residents seeking less dense areas from which to work remotely.[90]

Spring break

[edit]Since the early 1950s[91] the city had been a popular spring break resort. Glamorized as a destination in the 1963 movie Palm Springs Weekend,[92] the number of visitors grew and at times the gatherings had problems. In 1969 an estimated 15,000 people had gathered for a concert at the Palm Springs Angel Stadium and 300 were arrested for drunkenness or disturbing the peace.[93] In the 1980s, 10,000 or more college students would visit the city and form crowds and parties—and another rampage occurred in 1986[94] when Palm Springs Police in riot gear had to put down the rowdy crowd.[95] In 1990, due to complaints by residents, mayor Sonny Bono and the city council closed the city's Palm Canyon Drive to spring breakers and the downtown businesses, normally filled with tourists, lost money.[96]

Today

[edit]Tourism is a major factor in the city's economy with 1.6 million visitors in 2011.[47] The city has over 130 hotels and resorts, numerous bed and breakfasts, and over 100 restaurants and dining spots.[97] Events such as the Coachella and Stagecoach Festivals in nearby Indio attract younger people, making greater Palm Springs a more attractive area to retire.[98]

Following the 2008 recession, Palm Springs revitalized its Downtown, "the Village". Rebuilding started with the demolition of the Bank of America building in January 2012, with the Desert Fashion Plaza scheduled for demolition in 2013.[99]

In 2020, Christy Holstege became the mayor of Palm Springs, which made her the first openly bisexual mayor in the United States, as well as the first female mayor of Palm Springs.[100][101] The following year, Lisa Middleton became mayor, making her the first openly transgender mayor in California history.[102]

The movement behind mid-century modern architecture (1950s/60s era) in Palm Springs is backed by architecture enthusiasts, designers, and local historians to preserve many of Palm Springs' buildings and homes of famous celebrities, businessmen, and politicians. Stores sell furniture and gifts that feature a mid-century modern theme. The city holds a Modernism Week celebration every February, along with several related smaller events during the year.[103]

Geography

[edit]Palm Springs is located in the Sonoran Desert. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 95.0 square miles (246 km2), of which 94.1 square miles (244 km2) is land and 0.9 square miles (2.3 km2) (1%) is water. Located in the Coachella Valley desert region, Palm Springs is sheltered by the San Bernardino Mountains to the north, the Santa Rosa Mountains to the south, by the San Jacinto Mountains to the west and by the Little San Bernardino Mountains to the east.

Climate

[edit]Palm Springs has a hot desert climate (BWh in Köppen-Geiger classification), with over 300 days of sunshine and 4.93 inches (125.2 mm) of rainfall annually.[104] The wettest “rain year” on record was from July 1926 to June 1927 with 17.68 inches or 449.1 millimetres — of which 10.22 inches or 259.6 millimetres fell during three days in mid-February — and the driest from July 2001 to June 2002 with 0.40 inches or 10.2 millimetres.

The winter months are warm, with a majority of days reaching 70 °F or 21.1 °C and in January and February afternoons often see temperatures of 80 °F or 26.7 °C and on occasion reach over 90 °F or 32.2 °C, while, on average, there are 17 mornings annually dipping to or below 40 °F or 4.4 °C;[104] freezing temperatures occur in less than half of years. The lowest temperature recorded is 19 °F or −7.2 °C, on January 22, 1937.[105]

Summers are extremely hot, with daytime temperatures consistently surpassing 110 °F or 43.3 °C while overnight temperatures often remain above 80 °F or 26.7 °C. The mean annual temperature is 75.6 °F (24.2 °C). There are on average 176.6 afternoons with a high reaching 90 °F or 32.2 °C, and 100 °F or 37.8 °C can be seen on 114.8 afternoons.[104] The highest temperature on record in Palm Springs is 124 °F or 51.1 °C on July 5, 2024.[106][107] The climate of Palm Springs is suitable for some palm trees, although tropical types that need more water and humidity do not grow as well. [108]

On October 1, 2024 the temperature in Palm Springs reached 117 °F (47.2 °C), tying the record for the highest temperature in the United States in October, after the same temperature was reached in nearby Mecca on October 5, 1917.

| Climate data for Palm Springs, California (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1922–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 95 (35) |

99 (37) |

104 (40) |

112 (44) |

116 (47) |

123 (51) |

124 (51) |

123 (51) |

122 (50) |

117 (47) |

102 (39) |

93 (34) |

124 (51) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 70.5 (21.4) |

73.7 (23.2) |

80.6 (27.0) |

86.7 (30.4) |

94.7 (34.8) |

103.6 (39.8) |

108.6 (42.6) |

108.1 (42.3) |

101.8 (38.8) |

91.1 (32.8) |

78.7 (25.9) |

69.2 (20.7) |

88.9 (31.6) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 59.0 (15.0) |

61.7 (16.5) |

67.5 (19.7) |

72.9 (22.7) |

80.3 (26.8) |

88.2 (31.2) |

94.0 (34.4) |

94.0 (34.4) |

88.1 (31.2) |

77.8 (25.4) |

66.0 (18.9) |

57.7 (14.3) |

75.6 (24.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 47.6 (8.7) |

49.7 (9.8) |

54.4 (12.4) |

59.1 (15.1) |

65.9 (18.8) |

72.7 (22.6) |

79.4 (26.3) |

79.8 (26.6) |

74.4 (23.6) |

64.5 (18.1) |

53.4 (11.9) |

46.2 (7.9) |

62.3 (16.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 19 (−7) |

24 (−4) |

29 (−2) |

34 (1) |

36 (2) |

44 (7) |

54 (12) |

52 (11) |

46 (8) |

30 (−1) |

23 (−5) |

23 (−5) |

19 (−7) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.14 (29) |

1.11 (28) |

0.51 (13) |

0.09 (2.3) |

0.02 (0.51) |

0.00 (0.00) |

0.25 (6.4) |

0.14 (3.6) |

0.24 (6.1) |

0.20 (5.1) |

0.23 (5.8) |

0.68 (17) |

4.61 (117) |

| Average precipitation days | 2.7 | 3.1 | 1.9 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 2.7 | 16.9 |

| Source: NOAA[109][110] | |||||||||||||

Ecology

[edit]

The locale features a variety of native Low Desert flora and fauna. A notable tree occurring in the wild and under cultivation is the California Fan Palm, Washingtonia filifera.[111]

Wildlife

[edit]The fauna of Palm Springs is mostly species adapted to desert, temperature extremes and to lack of moisture. It is located within the Nearctic faunistic realm in a region containing an assemblage of species similar to Northern Africa.[112] Native fauna includes pronghorns, desert bighorn sheep, desert tortoise, kit fox, desert iguanas, horned lizards, chuckwalla, bobcats, mountain lions and Gila monsters. Other animals include ground squirrels, rock squirrels, porcupines, skunks, cactus mice, kangaroo rats, pocket gophers and raccoons.[113] Desert birds here include the iconic roadrunner, which can run at speeds exceeding 15 mph (24 km/h). Other avifauna includes the ladder-backed woodpecker, flycatchers, elf owls, great horned owls, sparrow hawks and a variety of raptors.[114]

The Sonoran Desert has more species of rattlesnakes (11) than anywhere else in the world.[115] The most common species is the extremely venomous Mojave green, which is considered the world's most dangerous rattlesnake. The largest rattle snake species here is the western diamondback rattlesnake, while other species include the black-tailed rattlesnake, tiger rattler and sidewinder rattler.[116] Palm Springs is home to tarantulas and various scorpion species, including the vinegaroon.[117]

Although black bears are not common in the Coachella Valley, bears have been observed in Palm Springs and other parts of California.[118]

Today, jaguars roam the northern Mexican dry-lands; however, they were previously common throughout the Coachella Valley. The last documented jaguar sighting in Palm Springs was in 1860.[119]

Neighborhoods

[edit]

The City of Palm Springs has developed a program to identify distinctive neighborhoods in the community.[120] Of the 45 neighborhoods,[120] 7 have historical and cultural significance.[121]

Movie Colony neighborhoods

[edit]The Movie Colony is just east of Palm Canyon Drive.[122] The Movie Colony East neighborhood extends further east from the Ruth Hardy Park.[123] These areas started growing in the 1930s as Hollywood movie stars built their smaller getaways from their Los Angeles area estates. Bob Hope, Frank Sinatra, Estée Lauder, Carmen Miranda and Bing Crosby built homes in these neighborhoods.

El Rancho Vista Estates

[edit]In the 1960s, Robert Fey built 70 homes designed by Donald Wexler and Ric Harrison in the El Rancho Vista Estates.[124] Noted residents included Jack LaLanne and comic Andy Dick.

Warm Sands

[edit]Historic homes in the Warm Sands area date from the 1920s and many were built from adobe.[125] It also includes small resorts and the Ramon Mobile Home Park. Noted residents have included screenwriter Walter Koch, artist Paul A. Grimm, activist Cleve Jones and actor Wesley Eure.[citation needed]

The Mesa

[edit]The Mesa started off as a gated community developed in the 1920s near the Indian Canyons.[126] Noted residents have included King Gillette, Zane Grey, Clark Gable, Carole Lombard, Suzanne Somers, Herman Wouk, Henry Fernandez, Barry Manilow and Trina Turk. Distinctive homes include Donald Wexler's "butterfly houses" and the "Streamline Moderne Ship of the Desert".[127]

Tahquitz River Estates

[edit]

Some of the homes in this neighborhood date from the 1930s. The area was owned by Pearl McCallum McManus, and she started building homes in the neighborhood after World War II ended. Dr. William Scholl (Dr. Scholl's foot products) owned a 10-acre (4.0 ha) estate here. Today the neighborhood is the largest neighborhood organization with 600 homes and businesses within its boundaries.[128]

Sunmor Estates

[edit]During World War II, the original Sunmor Estates area was the western portion of the Palm Springs Army Airfield.[129] Homes here were developed by Robert Higgins and the Alexander Construction Company. Actor and former mayor Frank Bogert bought his home for $16,000 and lived there for more than 50 years.[citation needed]

Historic Tennis Club

[edit]Impoverished artist Carl Eytel first set up his cabin on what would become the Tennis Club in 1937. Another artist in the neighborhood, who built his Moroccan-style "Dar Marrac" estate in 1924, was Gordon Coutts.[130] Other estates include Samuel Untermyer's Mediterranean style villa (now the Willows Historic Palm Springs Inn),[131] the Casa Cody Inn, built by Harriet and Harold William Cody (cousin of Buffalo Bill Cody)[132][133] and the Ingleside Inn,[134] built in the 1920s by the Humphrey Birge family. The neighborhood now has about 400 homes, condos, apartments, inns and restaurants.[135]

Las Palmas neighborhoods

[edit]To the west of Palm Canyon Drive are the Vista Las Palmas,[136] Old Las Palmas, and Little Tuscany neighborhoods.[137] These areas also feature distinctive homes, celebrity estates, and Albert Frey's private residential complex Villa Hermosa.[citation needed]

Racquet Club Estates

[edit]Historic Racquet Club Estates, located north of Vista Chino, is home to over five hundred mid-century modern homes from the Alexander Construction Company. "Meiselman" homes, and the famed Donald Wexler steel homes (having Class One historic designation) are also prominent in the area.[138] Racquet Club Estates was Palm Springs' first middle income neighborhood and became popular with Hollywood's elite in the 1950s and 60's.[52]: 41

Deepwell Estates

[edit]Deepwell Estates, the eastern portion of the square mile (2.6 km2) defined by South/East Palm Canyon, Mesquite, and Sunrise, contains around 370 homes, including notable homes architecturally and of celebrity figures. Among the celebrities who lived in the neighborhood are Jerry Lewis, Loretta Young, Liberace, and William Holden.[139][140]

Demographics

[edit]2010

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1940 | 3,434 | — | |

| 1950 | 7,660 | 123.1% | |

| 1960 | 13,468 | 75.8% | |

| 1970 | 20,936 | 55.4% | |

| 1980 | 32,359 | 54.6% | |

| 1990 | 40,181 | 24.2% | |

| 2000 | 42,807 | 6.5% | |

| 2010 | 44,552 | 4.1% | |

| 2020 | 44,575 | 0.1% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[141] | |||

The 2010 United States Census[142] reported that Palm Springs had a population of 44,552. The population density was 469.1 inhabitants per square mile (181.1/km2). The racial makeup of Palm Springs was 33,720 (75.7%) White (63.6% Non-Hispanic White),[4] 1,982 (4.4%) African American, 467 (1.0%) Native American, 1,971 (4.4%) Asian, 71 (0.2%) Pacific Islander, 4,949 (11.1%) from other races, and 1,392 (3.1%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 11,286 persons (25.3%).

The Census reported that 44,013 people (98.8% of the population) lived in households, 343 (0.8%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 196 (0.4%) were institutionalized.

There were 22,746 households, out of which 3,337 (14.7%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 5,812 (25.6%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 1,985 (8.7%) had a female householder with no husband present, 868 (3.8%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 1,031 (4.5%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 2,307 (10.1%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 10,006 households (44.0%) were made up of individuals, and 4,295 (18.9%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 1.93. There were 8,665 families (38.1% of all households); the average family size was 2.82.

The population was spread out, with 6,125 people (13.7%) under the age of 18, 2,572 people (5.8%) aged 18 to 24, 8,625 people (19.4%) aged 25 to 44, 15,419 people (34.6%) aged 45 to 64, and 11,811 people (26.5%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 51.6 years. For every 100 females, there were 129.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 133.8 males.

There were 34,794 housing units at an average density of 366.3 per square mile (141.4/km2), of which 13,349 (58.7%) were owner-occupied, and 9,397 (41.3%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 6.7%; the rental vacancy rate was 15.5%. 24,948 people (56.0% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 19,065 people (42.8%) lived in rental housing units.

During 2009–2013, Palm Springs had a median household income of $45,198, with 18.2% of the population living below the federal poverty line.[4]

2000

[edit]

As of the census[143] of 2000, there were 42,807 people, 20,516 households, and 9,457 families residing in the city. The population density was 454.2 inhabitants per square mile (175.4/km2). There were 30,823 housing units at an average density of 327.0 per square mile (126.3/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 78.3% White, 3.9% African American, 0.9% Native American, 3.8% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 9.8% from other races, and 3.1% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 23.7% of the population.

There were 20,516 out of which 16.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 34.0% were married couples living together, 8.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 53.9% were non-families. 41.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 18.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.1 and the average family size was 2.9.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 17.0% under the age of 18, 6.1% from 18 to 24, 24.2% from 25 to 44, 26.4% from 45 to 64, and 26.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 47 years. For every 100 females, there were 107.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 107.4 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $35,973 and the median income for a family was $45,318. Males had a median income of $33,999 versus $27,461 for females. The per capita income for the city was $25,957. About 11.2% of families and 15.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 28.2% of those under age 18 and 6.8% of those age 65 or over.

LGBTQ community

[edit]Palm Springs has one of the highest concentrations of same-sex couples of any community in the United States.[144][145] In 2010, 10.1% (2,307) of the city's households belong to same-sex married couples or partnerships, compared to the national average of 1%. Palm Springs has the fifth-highest percentage of same-sex households in the nation.[144]: 27 Former mayor Ron Oden estimated that about a third of Palm Springs is gay.[146] Over various times, the city has catered to LGBT tourists with an increasing number of events such as the annual Club Skirts Dinah Shore Weekend, as well as hosting various clothing-optional resorts and events.[147][148] Palm Springs is host to the Greater Palm Springs Pride Celebration. This celebration, held every year in November, includes events such as the Palm Springs Pride Golf Classic, the Stonewall Equality Concert, and a Broadway in Drag Pageant. The city also held same-sex wedding ceremonies at the iconic Forever Marilyn statue located downtown, before its relocation in 2014. In January 2018, Palm Springs ushered in America's first fully LGBTQ comprised city government.[149] Among notable establishments is Hunters Palm Springs.

Economy

[edit]Though celebrities still retreat to Palm Springs, many establish residences in other areas of the Coachella Valley. The city's economy now relies on tourism, and local government is largely supported by related retail sales taxes and the TOT (transient occupancy tax). The city hosts numerous festivals, conventions, and international events including the Palm Springs International Film Festival.

The world's largest rotating aerial tramcars[150] (cable cars) can be found at the Palm Springs Aerial Tramway. These cars, built by Von Roll Tramways,[150] ascend from Chino Canyon two and a half miles (4 km) up a steep incline to the station at 8,516 feet (2,596 m). The San Jacinto Wilderness is accessible from the top of the tram and there is a restaurant with notable views.

The Palm Springs Convention Center underwent a multimillion-dollar expansion and renovation under Mayor Will Kleindienst. The City Council Sub-Committee of Mayor Kleindienst and City Council Member Chris Mills selected Fentress Bradburn Architects[151] from Denver, Colorado for the redesign.

Numerous hotels, restaurants and attractions cater to tourists, while shoppers can find a variety of high-end boutiques in downtown and uptown Palm Springs. The city is home to 20 clothing-optional resorts including many catering to gay men.[152] Downtown Palm Springs shopping is anchored by historic La Plaza, built in 1936.

Top employers

[edit]According to the City's 2022 Annual Comprehensive Financial Report,[153] the top employers in the city are:

| No. | Employer | No. of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Palm Springs Unified School District | 2,584 |

| 2 | Desert Regional Medical Center | 2,459 |

| 3 | Agua Caliente Casino Palm Springs | 547 |

| 4 | City of Palm Springs | 470 |

| 5 | Walmart Supercenter | 387 |

| 6 | Margaritaville Resort Palm Springs | 251 |

| 7 | The Home Depot | 220 |

| 8 | Lowe's Home Improvement | 152 |

| 9 | Ace Hotel & Swim Club | 114 |

| 10 | Hilton Palm Springs Resorts | 108 |

Notable businesses

[edit]- Ace Hotel & Swim Club – a renovated mid-20th century motel.[154]

- Bird Medical Technologies[155]

- Colony Palms Hotel – opened in 1936 as The Colonial House by Las Vegas casino owner Al Wertheimer.

- KGAY, LGBT-themed radio station.[156]

- Raven Productions – a television production company based in Palm Springs.

- Earth Trek – a travel and adventure program produced by Raven.

Arts and culture

[edit]Annual cultural events

[edit]

- The Palm Springs International Film Festival and Palm Springs International Festival of Short Films ("ShortFest") present movie star-filled, red-carpet affairs in January and June respectively.

- Modernism Week, in February, is an 11-day event featuring mid-century modern architecture through films, lectures, tours and its Modernism Show & Sale. A four-day Modernism Week Preview is held in mid-October.[157]

- The Palm Springs Black History Committee celebrates Black History Month with a parade and town fair every February.[158]

- Agua Caliente Cultural Museum presents its annual Festival of Native Film & Culture[159] at the Camelot Theaters in central Palm Springs.

- The Club Skirts Dinah Shore Weekend, known as "The Dinah",[31] is an LGBT event billed as the "Largest Girl Party in the World" held each March.

- A circuit White Party is held in April, attracting 10,000 visitors.[31][160]

- The Palm Springs Cultural Center[161] hosts a number of annual events, including Cinema Diverse: The Palm Springs LGBTQ Film Festival, The Arthur Lyons Film Noir Festival,[162] the Certified Farmers' Markets and more.

- Palm Springs Desert Resorts Restaurant Week is held every June, featuring 10 days of dining at over 100 restaurants in the Coachella Valley.[163]

- The Caballeros, a gay men's chorus and member of GALA Choruses, has presented concerts since 1999.[164]

The following three parades, held on Palm Canyon Drive, were created by former Mayor Will Kleindienst:

- Palm Springs Annual Homecoming Parade is held on the Wednesday prior to the Friday night Palm Springs High School Homecoming Game.[165]

- The city sponsors a Veterans Day parade, concert and fireworks display since 1996.[166] It is one of 54 US Department of Veterans Affairs designated Regional Sites[167] for the national observance of Veterans Day.[168]

- Since 1992 the Palm Springs Festival of Lights Parade is held on the first Saturday of December.[169]

Ongoing cultural events

[edit]For many years, The Fabulous Palm Springs Follies was a stage-show at the historic Plaza Theatre featuring performers over the age of 55. Still Kicking: The Fabulous Palm Springs Follies is a 1997 Mel Damski short documentary film about the Follies. The Palm Springs Follies closed for good after the 2013–14 season.[170]

Starting in 2004, the city worked with downtown businesses to develop the weekly Palm Springs VillageFest. The downtown street fair has been a regular Thursday evening event, drawing tourists and locals alike to Palm Canyon Drive to stroll amid the food and craft vendors.[171]

Events related to films and film-craft are sponsored by the Desert Film Society.[172]

Public art

[edit]The city and various individuals have sponsored different public art projects in the city, including Robolights.[173][174] Numerous galleries and studios are located in the city and region.[175] The California Art Club has a chapter in Palm Springs.[176] The Desert Art Center of Coachella Valley was established in Palm Springs in 1950.[177]

Modern architecture

[edit]

Besides its tradition of mid-century modern architecture, Palm Springs and the region features numerous noted architects. Other (non-Mid-Century Modern) include[178] Edward H. Fickett, Haralamb H. Georgescu, Howard Lapham, and Karim Rashid.[179]

Museums and other points of interest

[edit]

- Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians

- Agua Caliente Cultural Museum[180] (presently located downtown at the Village Green)

- Indian Canyons (Palm Canyon,[181] Andreas Canyon, Murray Canyon)[182]

- Tahquitz Canyon,[183] wildlife area and one-time staging place for the outdoor "Desert Plays" in the 1920s[184]

- Tahquitz Falls, 60-foot (18 m) waterfall used as a scene in Frank Capra's 1937 film, Lost Horizon.[185]

- Agua Caliente Casino in Rancho Mirage

- Spa Resort Casino, which is based on the original hot springs of the town[186]

- Forever Marilyn sculpture by Seward Johnson in downtown Palm Springs[187]

- Moorten Botanical Garden and Cactarium

- Palm Springs Historical Society Museums[188] (and Village Green[189])

- Miss Cornelia White's "Little House" (railroad ties from the defunct Palmdale Railroad were used to build the house)

- The McCallum Adobe – the oldest remaining building, built in 1884

- Ruddy's General Store Museum – a 1930s general store[190]

- Palm Springs Air Museum – located at the Palm Springs International Airport

- Palm Springs Art Museum – originally developed as the Desert Museum

- Annenberg Theater[191]

- Palm Springs Walk of Stars

- San Jacinto Mountains

- Children's Discovery Museum of the Desert – in Rancho Mirage[192]

- Living Desert Zoo and Gardens – in Palm Desert, California

- Joshua Tree National Park

Notable restaurants include 1501 Uptown Gastropub, Chi Chi, Koffi, Sherman's Deli & Bakery, Tac/Quila, and Townie Bagels.

Sports

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2012) |

Baseball

[edit]Palm Springs is home to the Palm Springs Power, a summer collegiate baseball team currently playing in the California Premier Collegiate League.[193] The Power also operate the California Winter League a professional baseball showcase league. The league has run since 2010 playing games in January and February.[194] The winter league plays their games in Palm Springs Stadium and next to the stadium in Cerritos Park. Both sites also feature teams from the Palm Springs Collegiate League in the summer.[195]

The Palm Springs stadium was once the spring training site of the Major League Baseball California Angels (now the Los Angeles Angels) of the American League from 1961 to 1993.[196] The stadium also hosted spring training of the Chicago White Sox[197] in the late 1940s–1950s, the Oakland A's in the 1970s, and the 1950s minor league Seattle Rainiers of the Pacific Coast League also trained there.

Hockey

[edit]In 2019, Palm Springs was approved to become the home to an American Hockey League (AHL) expansion team to begin play for the 2021–22 season and serve as the development affiliate of the National Hockey League's 2021 expansion team, the Seattle Kraken.[198] However, the original project to build an arena in Palm Springs fell through, leading to the team's launch to be delayed by one year to the 2022–23 season.[199] The team, later named as the Coachella Valley Firebirds, then began building Coachella Valley Arena in nearby Thousand Palms, California.[200][201]

Tennis

[edit]The Palm Springs area features numerous major sports events, including the annual BNP Paribas Open in March, voted by professional players over several years in the early 21st century as the premier mandatory Tournament of the Year.[202] The Easter Bowl, sponsored by the United States Tennis Association is a showcase tournament for junior tennis players (girls and boys aged 12 to 18 years) held annually in March among several tennis centers of the Palm Springs area.[203]

Golf

[edit]

With more golf courses than any other region in California, Coachella Valley is the most popular golf vacation destination in California. Early golf courses in Palm Springs were the O'Donnell Golf Club (built by oil magnate Thomas A. O'Donnell)[204] and the El Mirador Hotel course, both of which opened in the 1920s.[24]: 120 After the Cochran-Odlum (Indio) and Shadow Mountain pitch and putt courses were built after World II, the first 18-hole golf course in the area was the Thunderbird Country Club, established 1951 in Rancho Mirage.[205][206] Thunderbird was designed by golf course architects Lawrence Hughes and Johnny Dawson[207] and in 1955 it hosted the 11th Ryder Cup championship.

In the 1970s the area had over 40 courses and in 2001 the 100th course was opened.[24]: 121 The area is also home to the PGA Tour's Humana Challenge in partnership with the Clinton Foundation (formerly the Bob Hope Chrysler Classic), the LPGA's ANA Inspiration and the Canadian Tour's Desert Dunes Classic.[208]

Soccer

[edit]The Palm Springs AYSO Region 80 plays in Section 1H of the American Youth Soccer Organization.[209][210]

Parks and recreation

[edit]City parks

[edit]- City parks include:[211]

- Baristo Park

- DeMuth Park

- Desert Healthcare (Wellness) Park

- Downtown Park

- James O. Jessie Desert Highland Unity Center[212]

- Dog Park (behind city hall)[213]

- Frances Stevens Park

- Ruth Hardy Park

- Sunrise Park

- Victoria Park

Recreation

[edit]- Boomers! is a family entertainment center in Cathedral City.[214]

- A city skatepark was designed after the noted Nude Bowl.[215]

- CNL Financial Group operates the Wet'n'Wild Palm Springs water park in the summer. (Formerly operated as Knott's Soak City by Cedar Fair Entertainment Company.)

In 1931 the Desert Riders was established.[216] Starting off as a social organization for the cream of Palm Springs society, the group sponsors horseback riding and trail building for equestrians, hikers, and bicyclists.[217] The Desert Riders were also significant in providing combination chuckwagon meals and rides through nearby canyons to hotel guests as Palm Springs developed its tourist industry.[218]

Government

[edit]City

[edit]Business owners in the village first established a Palm Springs Board of Trade in 1918, followed by a chamber of commerce; the city itself was established by election in 1938[219][220] and converted to a charter city, with a charter adopted by the voters in 1994.[221]

Presently the city has a council-manager type government, with a five-person city council that hires a city manager and city attorney. The mayor is directly elected and serves a four-year term. The other four council members also serve four-year terms, with staggered elections. The city is considered a full-service city, in that it staffs and manages its own police and fire departments including parks and recreation programs, public library,[222] sewer system and wastewater treatment plant, international airport, and planning and building services.

The city government is a member of the Southern California Association of Governments.[223]

Christy Holstege, who took office as mayor in December 2020, was the first female and the first openly bisexual mayor in the city's history, and the first openly bisexual mayor in American history.[100][101] Lisa Middleton, the first transgender mayor in California history, took office in 2021.[224]

Palm Springs' longest-tenured mayor was Frank Bogert (1958–66 and 1982–88). He was credited with leading the city as it evolved from a small resort town into a larger community.[225] Bogert's actions as mayor have proved controversial in recent years, as allegations that Bogert removed hundreds of citizens of color from a city neighborhood led to the removal of a statue on city property that honored him.[226]

Former entertainer Sonny Bono had the most recognizable name; Bono served from 1988 to 1992 and was eventually elected to the U.S. Congress.[227]

County

[edit]Palm Springs is in Supervisorial District 4 of Riverside County represented by Democrat V. Manuel Perez[228]

State

[edit]In the California State Legislature, Palm Springs is in the 19th Senate District, represented by Republican Rosilicie Ochoa Bogh, and in the 47th Assembly District, represented by Republican Greg Wallis.[229]

Federal

[edit]In the United States House of Representatives, Palm Springs is in California's 41st congressional district, represented by Republican Ken Calvert.[230]

Tribal Council

[edit]Palm Springs is the seat of government and the administrative capital for the tribal council of the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians.[231] The tribal government governs over parts of the city where reservation jurisdictions overlap.[232]

Education

[edit]Public schools

[edit]Public education in Palm Springs is under the jurisdiction of the Palm Springs Unified School District, an independent district with five board members.[233] The Palm Springs High School[234] is the oldest school in the district, built in 1938. Originally it was a K–12 school in the 1920s and had the College of the Desert campus from 1958 to 1964. And Raymond Cree Middle School in its current site since the mid-1960s.

Elementary schools in Palm Springs include:[235]

- Cahuilla Elementary School

- Cielo Vista Charter School (received a U.S. Department of Education National Blue Ribbon award in 2011, and U.S. Department of Education National Gold Ribbon Award in 2016[236])

- Katherine Finchy Elementary School[237] (received a U.S. Department of Education National Blue Ribbon award in 2011, and U.S. Department of Education National Gold Ribbon Award in 2016[236])

- Vista del Monte Elementary School

Alternative education is provided by the Ramon Alternative Center.[238]

Private schools

[edit]Private schools in Palm Springs and nearby communities include Desert Chapel Christian School (K-12), Desert Adventist Academy (K–8), Sacred Heart School (PS-8), St. Theresa (PreK–8), King's School – formerly known as Palm Valley School (K–8), Desert Christian (K–12), Marywood-Palm Valley School, and The academy.

In 2006 the Roman Catholic Diocese of San Bernardino built the Xavier College Preparatory High School[239] in Palm Desert.

Post-secondary education

[edit]The Desert Community College District, headquartered with its main campus, College of the Desert, is located in Palm Desert. California State University, San Bernardino and University of California, Riverside used to have satellite campuses available within the College of the Desert campus, but now have their own buildings in Palm Desert.

Private post-secondary education institutions include Brandman University (branch in Palm Desert),[240] California Desert Trial Academy College of Law (in Indio),[241] Kaplan College (Palm Springs),[242] University of Phoenix (Palm Desert),[243] Mayfield College (Cathedral City),[244] and California Nurses Educational Institute (Palm Springs).[245]

Media

[edit]Radio and television

[edit]Palm Springs is the 144th largest TV market as defined by AC Nielsen. The Palm Springs DMA is unique among TV markets as it is entirely located within only a small portion of Riverside County. Also, while many cities launched local television stations during the 1950s, Palm Springs did not have a local TV station until October 1968, when stations KPLM-TV (now KESQ) and KMIR-TV debuted. Prior to that time, Palm Springs was served by TV stations from the Los Angeles market, which were carried on the local cable system that began operations in the 1950s and which predated the emergence of local broadcast stations by more than a decade.

TV stations serving the Palm Springs and Coachella Valley area include:

- KDFX-CD Fox Channel 33 (Channel 11 on cable)

- KESQ-TV ABC, Channel 42 (Channel 3 on cable)

- KMIR-TV NBC, Channel 36 (Channel 13 on cable)

- KPSP-CD CBS, Channel 38 (Channel 2 on cable)

The CW, MyNetworkTV, PBS, and other networks are covered by low power TV stations in the market.

Additionally, Palm Springs and the surrounding area are served by AM and FM radio stations including the following:

News outlets and magazines

[edit]- The Desert Sun is the local daily newspaper serving Palm Springs and the Coachella Valley region. It is owned by the Gannett Corporation, parent company of USA Today.

- The Palm Springs Post is a digital-only news site and daily newsletter serving only Palm Springs. It is independently owned and operated.[246]

- Desert Magazine is a monthly lifestyle magazine delivered to 40,000 homes.

- The Desert Star Weekly (formerly the Desert Valley Star) is published in Desert Hot Springs, California.

- The Desert Daily Guide[247] is a weekly LGBT periodical.[248]

- Palm Springs Life is a monthly magazine; it also has publications on El Paseo Drive shopping in Palm Desert, desert area entertainment, homes, health, culture and arts, golf, plus annual issues on weddings and dining out.[249]

- The Palm Springs Villager[250][251] was published in the early 20th century until 1959.

- The Palm Canyon Times was published from 1993 to 1996.

- The Desert Post Weekly – Cathedral City.[252]

- The Public Record – Palm Desert, is a business and public affairs weekly.[253]

Infrastructure

[edit]Libraries

[edit]The city's library was started in 1924 and financed by Martha Hitchcock. It expanded in 1940 on land donated to the newly incorporated city by Dr. Welwood Murray and was financed through the efforts of Thomas O'Donnell.[254] The present site now operates as a branch library, research library for the Palm Springs Historical Society, and tourism office for the Palm Springs Bureau of Tourism.[255]

Transportation

[edit]One of the first transportation routes for Palm Springs was on the Bradshaw Trail, an historic overland stage coach route from San Bernardino to La Paz, Arizona. The Bradshaw Trail operated from 1862 to 1877. In the 1870s the Southern Pacific Railroad expanded its lines into the Coachella Valley.[256]

Modern transportation services include:

- Palm Springs International Airport serves Palm Springs and the Coachella Valley.

- Historical note: during World War II it was operated as the Palm Springs Army Airfield.

- SunLine Transit Agency provides bus service in the Coachella Valley.

- Morongo Basin Transit Authority provides bus service to and from Morongo Basin communities.

- Amtrak's Sunset Limited and Texas Eagle form a single train which stops thrice weekly at the Palm Springs Amtrak station.

- Amtrak's Amtrak Thruway connects Palm Springs to Bakersfield, Claremont, Indio, La Crescenta, Ontario, Pasadena, Riverside and San Bernardino.[257] Curbside Thruway bus stops are located in Downtown Palm Springs and at the airport.

- Historical note: the Southern Pacific Railroad Argonaut served Palm Springs from 1926 to 1961; and its Imperial served the city from 1931 to 1967.[258]

- Greyhound Bus Lines has a stop (no ticketing) at the Palm Springs Amtrak station.[259]

- Flixbus provides service between Palm Springs and several destinations in Southern California and Arizona.[260]

Highways include:

SR 111 – California State Route 111, which intersects the city.

SR 111 – California State Route 111, which intersects the city. I-10 – Interstate 10 generally runs north of the city.

I-10 – Interstate 10 generally runs north of the city. SR 74 – The Pines to Palms Scenic Byway (California State Route 74) runs from the coast, over the San Jacinto Mountains to nearby Palm Desert several miles southeast of Palm Springs.

SR 74 – The Pines to Palms Scenic Byway (California State Route 74) runs from the coast, over the San Jacinto Mountains to nearby Palm Desert several miles southeast of Palm Springs. SR 62 – California State Route 62 (a Blue Star Memorial Highway) intersects I-10 northwest of the city and runs northeast to Joshua Tree and the Colorado River.

SR 62 – California State Route 62 (a Blue Star Memorial Highway) intersects I-10 northwest of the city and runs northeast to Joshua Tree and the Colorado River.

Cemeteries

[edit]In 1890, the Jane Augustine Patencio Cemetery was established on Tahquitz Way with the burial of Jane Augustine Patencio.[68] It is maintained by the Agua Caliente Tribe.

The Welwood Murray Cemetery was started by hotel operator Welwood Murray in 1894 when his son died.[24]: 46 [261] It is maintained by the Palm Springs Cemetery District,[262] which also maintains the Desert Memorial Park in Cathedral City.

Also in Cathedral City is the Forest Lawn Cemetery, maintained by Forest Lawn Memorial-Parks & Mortuaries.

Notable people

[edit]Over 400 Palm Springs and Coachella Valley residents have been recognized on the Palm Springs Walk of Stars.

In popular culture

[edit]The Palm Springs area has been a filming location, topical setting, and storyline subject for many films, television shows, and works of literature. The April 20, 1958 "Gunsmoke" radio episode "The Partners" features a prominent commercial lauding Palm Springs.

See also

[edit]- Leonore Annenberg and Walter Annenberg – Rancho Mirage residents involved in Palm Springs activities. Their Sunnylands estate hosted many dignitaries and celebrities.

- History of the Jews in the U.S. – Palm Springs – for information about the Jewish community in Palm Springs.

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Riverside County – includes listings in Palm Springs and nearby cities

- Pumilia novaceki – an extinct iguanid from the Palm Springs area.

- United States cities by crime rate (40,000–60,000) – for a comparative table on crime rates in Palm Springs

- Desert Regional Medical Center

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Palm Springs". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

- ^ "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on November 3, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Palm Springs (city) QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 6, 2012. Retrieved February 11, 2015.

- ^ Seiler, Hansjakob; Hioki, Kojiro (1979). Cahuilla Dictionary. Malki Museum Press. p. 183.

- ^ Siva Sauvel, Katherine; Munro, Pamela (1982). Chem'ivillu' (Let's Speak Cahuilla). Malki Museum Press.

- ^ Mathews, Joe (February 1, 2018). "Canadians love the California desert. Why not let them have it, eh?". The Sacramento Bee. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- ^ "Parks & Recreation". City of Palm Springs. Archived from the original on August 16, 2014. Retrieved August 28, 2014.

- ^ a b Baker, Christopher P. (2008). Explorer's Guide Palm Springs & Desert Resorts: A Great Destination. The Countryman Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-1581570489.

- ^ a b c Vechten, Ken Van (2010). Insider's Guide to Palm Springs. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 17; ISBN 978-0762761579

- ^ Smolinski, Dick and Craig A. Doherty (1994). The Cahuilla. Rourke Publications. p. 4. ISBN 978-0866255271

- ^ Palmer, Roger C. (2012). Palm Springs. Arcadia Publishing. p. ix. ISBN 978-0738589138.

- ^ Gray-Kanatiiosh, Barbara A. (2010). Cahuilla. ABDO Publishing Company. p. 4. ISBN 978-1617849077

- ^ Niemann, Greg (2006). Palm Springs Legends: Creation of a Desert Oasis. Sunbelt Publications, Inc. p. 15. ISBN 978-0932653741.

- ^ Bean, Lowell L. (1974). Mukat's People: The Cahuilla Indians of Southern California. University of California Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0520026278

- ^ Baker, Christopher P. (2008). Explorer's Guide Palm Springs & Desert Resorts: A Great Destination. The Countryman Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-1581570489

- ^ Whitley, David S. (1996). A Guide to Rock Art Sites: Southern California and Southern Nevada. Mountain Press Publishing. pp. 94–96. ISBN 978-0878423323

- ^ Baker, Christopher P. (2008). Explorer's Guide Palm Springs & Desert Resorts: A Great Destination. The Countryman Press. p. 216. ISBN 978-1581570489

- ^ Niemann, Greg (2006). Palm Springs Legends: Creation of a Desert Oasis. Sunbelt Publications, Inc., p. 259. ISBN 978-0932653741

- ^ Eargle, Dolan H. (2008). Native California: An Introductory Guide to the Original Peoples From Earliest to Modern Times. Trees Company Press. p. 278. ISBN 978-0937401118

- ^ Wilkerson, Lyn (2009). Slow Travels – California. Lulu Press, Inc. p. 96. ISBN 978-0557088072

- ^ Wares, Donna (2008). Great Escapes: Southern California. The Countryman Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0881507799

- ^ "2010 Census CPH-T-6. Table 1. American Indian and Alaska Native Population by Tribe for the United States: 2010" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 9, 2014. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Niemann, Greg (2006). Palm Springs Legends: creation of a desert oasis. San Diego, CA: Sunbelt Publications. p. 286. ISBN 978-0932653741. OCLC 61211290. (here for Table of Contents)

- ^ a b c d e Lech, Steve (2004). Along the Old Roads: A History of the Portion of Southern California that became Riverside County: 1772–1893. Riverside, CA: Steve Lech. p. 902. OCLC 56035822.

- ^ Gittens, Roberta (November 1992). "A Palm-filled Oasis: Palm Springs and the Desert Communities of the Coachella Valley". Art of California. Vol. 5, no. 5. p. 45. ISSN 1045-8913. OCLC 19009782.

- ^ "City of Palm Springs: History". Archived from the original on December 20, 2010. Retrieved August 18, 2010.

- ^ Bright, William (1998). Fifteen Hundred California Place Names. University of California Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-0520212718. Retrieved April 5, 2013.

- ^ Gudde, Erwin Gustav; Bright, William (1998). California Place Names: The Origin and Etymology of Current Geographical Names (4th ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 277. ISBN 978-0520242173. LCCN 97043168.

'The fine large trees which mark the course of the run have furnished the name ...' (Whipple 1849:7–8). The place is shown as Big Palm Springs on the von Leicht-Craven map of 1874.

- ^ a b Wild, Peter (2007). Tipping the Dream: A Brief History of Palm Springs. Johannesburg, CA: The Shady Myrick Research Project. p. 228. OCLC 152590848.

- ^ a b c d Colacello, Bob (June 1999). "Palm Springs Weekends" (PDF). Vanity Fair. Becker, Jonathan (photographs). pp. 192–211. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 11, 2013.

- ^ Palm Valley Land Co. (c. 1888). Views in Palm Valley...: The earliest fruit region in the state...now on sale by Biggs, Fergusson & Co. San Francisco. OCLC 82950785.

- ^ Two early, but fictional, visitors were six-year-old Mary and her cousin Jack. See: Foster, Ethel T. (1913). "A Visit to Palm Springs". Little Tales of the Desert. Villa, Hernando G. (illustrations). Los Angeles: Kingsley, Mason and Collins Co. p. 23. ISBN 978-1176787933. LCCN 13025440. OCLC 3726918.

Just beyond [the Indian village] was Palm Springs settlement itself, with lots of tents, several houses, a store and [Dr. Murray's Hotel]....They visited the funny little cottages with their roofs and sides all covered with big palm leaves instead of boards. Then they went up to the hot springs.

- ^ Brown, Renee (July 24, 2014). "Palm Springs History: Pioneers survived summer". The Desert Sun. Palm Springs: Gannett. Archived from the original on July 29, 2021.

- ^ James, George Wharton; Eytel, Carl (illustrator) (1906). The Wonders of the Colorado Desert (Southern California). Boston: Little, Brown and Company. p. 547. ISBN 978-1103733613. LCCN 06043916. OCLC 2573290. (Available as a pdf file through the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

- Wonders is illustrated with over 300 drawings by desert artist Carl Eytel. Many of those drawings, including the Title Page figure, are used throughout Steve Lech's extensive history of early Riverside County. See: Along the Old Roads (cited above).

- ^ Reviews of Wonders included:

- Adams, Cyrus C. (March 2, 1907). "Wonders of the Far West: George Wharton James's New Book on the Colorado Desert" (PDF). The New York Times Saturday Review of Books. Retrieved August 30, 2012.

- "A Guide to the New Books". The Literary Digest. Vol. XXXIV, no. 7. February 16, 1907. pp. 263–264.

This elaborate treatise is a distinct contribution to the literature of the natural wonders of our country.

- Gilmour, John Hamilton (February 3, 1907). "The Wonders of the Colorado Desert, California". San Francisco Call. Vol. 101, no. 65. p. Magazine, 3.

He has written admirably and knowingly ... and this ... is in line with his previous works.

- ^ Starr, Kevin (1997). "1. Good Times on the Coast: Affluence and the Anti-Depression". The Dream Endures: California Enters the 1940s. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 512. ISBN 978-0195100792.

- ^ Desert Inn (1923). The Desert Inn: Where Desert and Mountains Meet, Palm Springs, California. Los Angeles: Times-Mirror Print & Binding House. p. 24. OCLC 82839637.

- ^ "Historic Sites: Desert Inn". Palm Springs Life. Archived from the original on August 21, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2013.

County of Riverside Historical Marker No. 044; 123 North Palm Canyon (image of marker with 1908 date)

- ^ Bright, Marjorie Belle (1981). Nellie's Boardinghouse: a dual biography of Nellie Coffman and Palm Springs. Palm Springs: ETC Pub. p. 247.

- ^ Janss, Betty; Frashers Inc. (1933). Palm Springs California: presented with the compliments of the Desert Inn. Palm Springs: Desert Inn. p. 34. OCLC 427216166.

- ^ Brown, Renee (March 28, 2015). "Nellie Coffman's hospitality helped Palm Springs grow". The Desert Sun. Gannett.

- ^ Chase, J. Smeaton (1987) [1920]. Our Araby: Palm Springs and the Garden of the Sun. Pasadena, CA: Star-News Publishing Co. p. 83. ISBN 978-0961872403. LCCN 24010428. OCLC 6169840.

- ^ a b Bowhart, W. H.; Hector, Julie; McManus, Sally Mall; Coffman Kieley, Elizabeth (April 1984). "The McCallum Centennial – Palm Springs' founding family". Palm Springs Life. Archived from the original on August 14, 2011. Retrieved February 24, 2012.; and, Ainsworth, Katherine (1996) [1973 Palm Springs Desert Museum]. The McCallum Saga: The Story of the Founding of Palm Springs. Palm Springs: Palm Springs Public Library. p. 245. ISBN 978-0961872410. LCCN 96052785. OCLC 36066124. OCLC 799840

- ^ During World War II, the hotel was taken over and operated as a United States Army General Hospital, named in honor of Surgeon General George H. Torney.

- ^ Wild, Peter (2011). Heiress of Doom: Lois Kellogg of Palm Springs. Tucson, AZ: Estate of Peter Wild. p. 449. OCLC 748583736.

- ^ a b Palmer, Roger C. (2011). Palm Springs (Then & Now). Charleston, SC: Arcadia. p. 95. ISBN 978-0738589138. LCCN 2011932500. OCLC 785786600.

- ^ Brown, Renee (May 21, 2016). "Movie stars began flocking to Palm Springs in the 1930s". The Desert Sun. Palm Springs. Gannett.

- ^ Rippingale, Sally Presley (1985) [1984]. The History of the Racquet Club of Palm Springs. Yucaipa, CA: US Business Specialties. p. 146. LCCN 85226534. OCLC 13526611.. Also see: Turner, Mary L. and Turner, Cal A. (photography) (2006). The Beautiful People of Palm Springs. Sedona, AZ: Gene Weed. 154 pp. ISBN 978-1411634886 OCLC 704086361. The Racquet Club would cater to the Hollywood elite for decades.

- ^ a b Carr, Jim (1989). Palms Springs and the Coachella Valley. Helena, MT: American Geographic Publishing. p. 112. ISBN 978-0938314684. LCCN 91166185. OCLC 25026437.

- ^ Kleinschmidt, Janet (September 2005). "Remembering The Chi Chi: 'A hip little place to come for wealthy people.'". Palm Springs Life.; and, Johns, Howard (September 2007). "In the Swing: Dinner clubs and lounges echo the days (and nights) of Palm Springs' famed Chi Chi club". Palm Springs Life.

- ^ a b Meeks, Eric G. (2014) [2012]. The Best Guide Ever to Palm Springs Celebrity Homes. Horatio Limburger Oglethorpe. ISBN 978-1479328598.

- ^ Fessier, Bruce. "Mob looks to win big with casinos in valley". The Desert Sun. Gannett.

- ^ Brown, Renee (April 9, 2016). "Gambling in desert was 'economic driver' in 1930s". The Desert Sun. Palm Springs: Gannett.

- ^ "21 Nov 1930, 40 – The Los Angeles Times at Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com.

- ^ Howser, Huell; Bogert, Frank; McManus, Sally; Pitts, Larry (September 27, 2010). "Palm Springs Plaza Update – Palm Springs Week (35)". California's Gold. Chapman University Huell Howser Archive. Archived from the original on May 18, 2013. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ Murphy, Gavin (October 28, 1988). "World Market Plan Dies". Desert Sun (Palm Springs, CA).

- ^ "Clipped From The Desert Sun". The Desert Sun. January 9, 1958. p. 22 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Murphy, Gary (March 6, 1992). "Merchants bemoan loss in Palm Springs of I. Magnin Store". Desert Sun (Palm Springs, CA).

- ^ "Saks will open here tomorrow". Desert Sun (Palm Springs, CA). October 15, 1959.

- ^ Staff writer(s) (October 16, 1967). "'New Era' Launched as I. Magnin Opens". The Desert Sun. Vol. 41, no. 62. Retrieved December 27, 2019.

- ^ Staff writer(s) (March 6, 1969). "Ground Broken Today for New Major Store". The Desert Sun. Vol. 42, no. 183. Retrieved December 27, 2019.

- ^ a b Desert Memories: Historic Images of the Coachella Valley. Palm Springs: The Desert Sun. 2002. p. 128. ISBN 978-1932129014. OCLC 50674171.

- ^ "Palm Springs Army Air Field (historical)". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ "Palm Springs Visitors Set Fashion Pace: Desert Resort Hotels And Clubs Are Crowded To Capacity". The Pittsburgh Press. March 26, 1941. p. 28. Retrieved September 30, 2012.

- ^ Johnson, Erskine (December 18, 1949). "Palm Springs An Odd Place". The Pittsburgh Press. Retrieved September 30, 2012.

- ^ "Torney General Hospital". Historic California Posts. The California State Military Museum.

- ^ a b Robinson, Nancy (1992). Palm Springs History Handbook. Palm Springs: Palm Springs Public Library. p. 41. OCLC 31595834.

- ^ Wills, Eric (May/June 2008). "Palm Springs Eternal", Preservation, Vol. 60, Issue 3, pp. 38–45

- ^ Goldberger, Paul (May–June 2008). "The Modernist Manifesto". Preservation. Vol. 60, no. 3. pp. 30–35.

- ^ a b Culver, Lawrence (2010). "Chapter 5: The Oasis of Leisure – Palm Springs before 1941; and Chapter 6: Making of Desert Modern – Palm Springs after World War II". The Frontier of Leisure: Southern California and the Shaping of Modern America. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 317. ISBN 978-0195382631. LCCN 2009053932. OCLC 620294456, 464581464

- ^ Kray, Ryan M. (February 2004). "The Path to Paradise: Expropriation, Exodus and Exclusion in the Making of Palm Springs". Pacific Historical Review. 73 (1): 85–126. doi:10.1525/phr.2004.73.1.85. ISSN 0030-8684. JSTOR 10.1525/phr.2004.73.1.85. OCLC 4635437946, 361566392 (subscription required)

- ^ Kray, Ryan M. (2009). Second-class Citizenship at a First-class Resort: Race and Public Policy in Palm Springs. Irvine: University of California (PhD thesis). p. 407. ISBN 978-1109197983. OCLC 518520550.

- ^ "Palm Springs: Green and Grows the Desert" (PDF). Fortune. February 1961. pp. 122–127. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 29, 2017.

Before President Eisenhower went to Palm Springs...in 1954, [it] was only a regional resort. Overnight it became a winter resort with national drawing power.

- ^ A book of Doisneau's photographs was published in 2010. Doisneau, Robert; Dubois, Jean-Paul (Forward) (2010). Palm Springs 1960. Paris: Flammarion. p. 9. ISBN 978-2080301291. LCCN 2010442384. OCLC 491896174.

- ^ "Section 14: The Agua Caliente Tribe's Struggle for Sovereignty in Palm Springs, California". NMAI Magazine. Retrieved December 2, 2022.

- ^ Goolsby, Denise. "Palm Springs Section 14 exhibit set for Smithsonian". The Desert Sun. Retrieved December 2, 2022.

- ^ Amighpey, Shadi (September 30, 2021). "City Council approves relocating Bogert statue, Section 14 apology, exploring reparations". The Palm Springs Post. Retrieved December 2, 2022.

- ^ Murphy, Denise Goolsby and Rosalie. "'It was beautiful for the white people:' 1960s still cast a shadow of distrust over Palm Springs". The Desert Sun. Retrieved December 2, 2022.

- ^ White, John. "I-Team digs into what really happened in the forced removal of Section 14 families in Palm Springs". Channel 3 News. Retrieved December 13, 2024.

- ^ "Monument Relocation Resolution NOT FINALDraft.pdf" (PDF). Dropbox. Retrieved December 2, 2022.

- ^ Ingrassia, Jake (September 30, 2021). "Palm Springs to apologize for Section 14 destruction; moves forward with process to remove Frank Bogert statue". KESQ. Retrieved December 2, 2022.

- ^ Talkington, Mark (October 11, 2022). "Legal case around removal of Frank Bogert statue from in front of City Hall stopped in its tracks after judge's ruling ⋆ The Palm Springs Post". The Palm Springs Post. Retrieved December 2, 2022.

- ^ "Black, Mexican families seek restitution for Palm Springs evictions". ABC7 Los Angeles. November 30, 2022. Retrieved December 2, 2022.

- ^ See:

- Amory, Cleveland (March 12, 1961). "Palm Springs Is Really An Incredible Place". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved October 2, 2012.

It is Hollywood without the wood. Beverly Hills without the hills and Los Angeles without the—well, freeways.

- "Palm Springs Now Top Desert Resort". The Sun. Vancouver, Canada. January 5, 1968. Retrieved October 2, 2012.

One finds 21 golf courses sprinkled across the golden sands of the desert. More than 3,650 swimming pools dot the landscape.

- "Palm Springs: Outdoors Paradise". St. Petersburg Independent. St. Petersburg, FL. January 11, 1972. p. 4-D. Retrieved October 2, 2012.

Moonlight steak [horseback] rides, breakfast rides and group rides are a way of life in the...desert resort.

- Fix, Jack V. (June 9, 1977). "Palm Springs Place Where Rich Retire". The Pittsburgh Press. UPI. p. B-1. Retrieved October 2, 2012.

This desert town...with 5,000 private swimming pools, 38 golf courses and homes selling for 'only $250,000 down' is probably the most wealthy retirement community in the world. Yet it is an area of 37 mobile home parks and senior citizens, 32 per cent of whom...reported an income of less than $4,000 a year.

- Eichenbaum, Marlene (June 9, 1979). "Palm Springs: It's a plush resort for rich and poor alike". The Gazette. Montreal, Canada. p. T-2. Retrieved October 2, 2012.

...it has long been a haven for the rich and famous....it [also] offers a wide choice of moderately-priced accommodations....