2021 in reptile paleontology

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

This list of fossil reptiles described in 2021 is a list of new taxa of fossil reptiles that were described during the year 2021, as well as other significant discoveries and events related to reptile paleontology that occurred in 2021.

Squamates

[edit]New taxa

[edit]| Name | Novelty | Status | Authors | Age | Type locality | Location | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Rage et al. |

Eocene |

|||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Scarpetta |

A member of Iguania. Genus includes new species C. lovei. |

|||||

|

Sp. nov |

Valid |

Willman, Konishi & Caldwell |

A plioplatecarpine mosasaur. |

|||||

|

Sp. nov |

Valid |

Scarpetta, Ledesma & Bell |

Olla Formation |

A species of Elgaria. |

||||

|

Sp. nov |

Valid |

Jurestovsky |

A species of Heterodon. |

|||||

|

Sp. nov |

Valid |

Bochaton, Charles & Lenoble |

Quaternary |

|

||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

In press |

Ikeda et al. |

A member or a relative of the group Monstersauria. Genus includes new species M. kamitakiens. |

|||||

|

Sp. nov |

Valid |

Bolet et al. |

A lizard of uncertain phylogenetic placement. |

| ||||

|

Sp. nov |

In press |

Smith & Scanferla |

Eocene |

|||||

|

Sp. nov |

Valid |

Georgalis, Čerňanský & Klembara |

Probably late Eocene |

A member of Anguimorpha belonging to the family Palaeovaranidae. |

||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Martinelli, Agnolín & Ezcurra |

Possibly a member of Polyglyphanodontia. The type species is P. occultato. |

|||||

|

Gen. et comb. nov |

Valid |

Smith & Habersetzer |

Eocene |

Messel Formation |

A palaeovaranid anguimorph. |

| ||

|

Gen. et comb. nov |

Valid |

Georgalis, Rabi & Smith |

Probably middle or late Eocene |

A snake belonging to the group Booidea. The type species is "Palaeopython" filholii Rochebrune (1880). |

||||

|

Sp. nov |

Valid |

Longrich et al. |

A mosasaur. |

|||||

|

Sp. nov |

Valid |

Thorn et al. |

Late Oligocene |

An egerniine skink. |

||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Wagner et al. |

A member of the family Agamidae. Genus includes new species P. monocoli. |

|||||

|

Sp. nov |

Valid |

Georgalis, Čerňanský & Klembara |

Probably Oligocene |

Quercy Phosphorites Formation |

A member of the family Lacertidae belonging to the subfamily Gallotiinae. |

|||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Smith & Scanferla |

||||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Suarez et al. |

A member of the family Paramacellodidae. The type species is S. pawhuskai. |

| ||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Disputed |

Longrich et al. |

Ouled Abdoun Basin |

A mosasaurine mosasaur. Genus includes new species X. calminechari. Sharpe, Powers & Caldwell (2024) considered X. calminechari to be nomen dubium, and interpreted its type material as subjected to a forgery.[20] |

|

Research

[edit]- A study on the evolution of tooth complexity in squamates, based on data from extant and fossil taxa, is published by Lafuma et al. (2021).[21]

- A study on the diversity of jaw sizes, lower jaw shape and morphology of teeth in Cretaceous squamates is published by Herrera-Flores, Stubbs & Benton (2021), who interpret their findings as indicating that a substantial expansion of ecomorphological diversity of squamates occurred in the mid-Cretaceous, 110–90 Ma, before the first rise in taxonomic diversity of this group in the Campanian.[22]

- A study on the dietary preferences of lizards from the Upper Cretaceous Iharkút vertebrate locality (Hungary) is published by Gere et al. (2021).[23]

- A study on the locomotion of five Cretaceous lizards, and on its implications for the knowledge of the ancestral locomotion type in lizards, is published by Villaseñor-Amador, Suárez & Cruz (2021), who interpret their findings as indicating that Huehuecuetzpalli mixtecus was bipedal while Tijubina pontei was facultatively bipedal.[24]

- Augé, Dion & Phélizon (2021) describe the lizard fauna from the Paleocene locality of Montchenot (Paris Basin, France), and evaluate the implications of this fauna for the knowledge of diversity changes of European squamate faunas across the Paleocene/Eocene boundary.[25]

- Čerňanský et al. (2021) describe new fossil material of lizards from two Miocene sites in Kutch (Gujarat, India), providing new information on the composition and biogeography of South Asian lizard faunas during the Miocene.[26]

- Revision of the fossil material of lizards and snakes from the Miocene of the Saint-Gérand-le-Puy area (France), including the first records of Ophisaurus holeci and the gallotiine lacertid Janosikia from France, is published by Georgalis & Scheyer (2021).[27]

- A study on the fossil record of lizards and snakes from the Guadeloupe Islands, assessing their evolutionary history and diversity over the past 40,000 years, is published by Bochaton et al. (2021), who interpret their findings as indicative of a massive extinction of Guadeloupe's snakes and lizards following European colonization, preceded by thousands of years of coexistence with earlier Indigenous populations.[28]

- A study on the shape and size variation in the maxillae of extant New Zealand diplodactylids, and on its implications for the knowledge of the affinities of subfossil diplodactylid remains, is published by Scarsbrook et al. (2021).[29]

- A study aiming to assess the phylogenetic value of lacertid jaw elements from four Oligocene localities in France, and evaluating their implications for the knowledge of the lacertid species richness in the Oligocene, is published by Wencker et al. (2021).[30]

- A study on the osteological variability in extant species of lacertid lizards, and on its implications for species delimitation in fossil lacertids, is published by Tschopp et al. (2021).[31]

- Fossils of Gallotia goliath are described for the first time from the El Hierro island (Canary Islands) by Palacios-García et al. (2021), providing the first evidence of the possible coexistence of two giant fossil species of Gallotia on the same island.[32]

- Fossil material of a large anguimorph lizard, possibly a member of Varaniformes and potentially one of the largest Mesozoic terrestrial lizards, is described from the Upper Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) Basturs-1 site (Spain) by Cabezuelo Hernández et al. (2021).[33]

- A study on the anatomy and phylogenetic relationships of Tetrapodophis amplectus is published by Caldwell et al. (2021), who reinterpret this squamate as a dolichosaur.[34]

- A yaguarasaurine mosasauroid is reported from the Cenomanian-Turonian beds of Coahuila (Mexico) by Jiménez-Huidobro et al. (2021), representing the earliest occurrence of a non-aigialosaur mosasauroid from North America reported to date.[35]

- Redescription and a study on the geographic provenance of the fossil material of "Liodon" asiaticum is published by Bardet et al. (2021).[36]

- One to seven month-long life histories of specimens of Platecarpus tympaniticus and Clidastes propython collected from chalk deposits of the Western Interior Seaway and Mississippi Embayment in Kansas and Alabama are reconstructed by Travis Taylor et al. (2021), who interpret their findings as indicative of semi-regular travels of these mosasaurs from marine to freshwater coastal environments and consumption of freshwater.[37]

- Fossil material providing the first evidence of the presence of Plotosaurus-type mosasaurs in the Northwestern Pacific Ocean reported to date is described from the Campanian Hiraiso Formation and Maastrichtian Isoai Formation (Japan) by Kato et al. (2021).[38]

- First confirmed non-dental mosasaur remains from the Maastrichtian Breien Member of the Hell Creek Formation (North Dakota, United States) are described by Van Vranken & Boyd (2021).[39]

- A study on the evolutionary history of snakes, aiming to determine possible impact of the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event on the evolution and dispersal of snakes, is published by Klein et al. (2021).[40]

- An assemblage of vertebrae of Palaeophis africanus, representing the most abundant material of this snake reported to date and providing new information on its anatomy, is described from the Eocene (Lutetian) of Togo by Georgalis et al. (2021).[41]

- A vertebra of Naja romani is described from the Miocene (Turolian) Solnechnodolsk locality (Northern Caucasus, Russia) by Syromyatnikova, Tesakov & Titov (2021), representimg the latest known record of this species and expanding its geographic and geological range.[42]

- Biton & Bailon (2021) report the discovery of fossil material of adders belonging to the Bitis arietans complex from the early Late Pleistocene of the Qafzeh cave (Israel), representing the northernmost record of the expansion of these adders outside Africa reported to date, and evaluate the implications of this finding for the knowledge of the climatic and environmental conditions in the surroundings of the Qafzeh Cave during the Mousterian Homo sapiens occupations.[43]

Ichthyosauromorphs

[edit]New taxa

[edit]| Name | Novelty | Status | Authors | Age | Type locality | Location | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

In press |

Zverkov et al. |

An early ichthyosaur of uncertain phylogenetic placement, possibly with toretocnemid or parvipelvian affinities. Genus includes new species A. incognita. |

|||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Fernández et al. |

An ichthyosaur belonging to the family Ophthalmosauridae. Genus includes new species C. gaspariniae. |

|||||

|

Sp. nov |

Sander et al. |

| ||||||

| Kazakhstanosaurus[47] | Gen. et sp. nov | Bolatovna and Maksutovich | Late Jurassic | An ichthyosaur belonging to the family Ophthalmosauridae. Genus includes new species K. shchuchkinensis and K. efimovi. | ||||

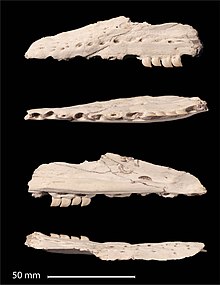

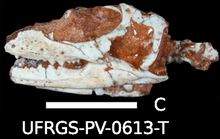

| Kyhytysuka[48] | Gen. et comb. nov | Cortés, Maxwell, and Larsson | Early Cretaceous (Barremian-Aptian) | Paja Formation | An ichthyosaur belonging to the family Ophthalmosauridae. The type species is "Platypterygius" sachicarum Páramo (1997). |  | ||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Barrientos-Lara and Alvarado-Ortega |

An ichthyosaur belonging to the family Ophthalmosauridae. The type species is J. meztli |

|||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Barrientos-Lara & Alvarado-Ortega |

An ichthyosaur belonging to the family Ophthalmosauridae. The type species is P. yacahuitztli |

|||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Campos et al. |

Late Jurassic |

An ichthyosaur belonging to the family Ophthalmosauridae. Genus includes new species S. argentina |

Research

[edit]- Description of anatomy of the palate of Chaohusaurus brevifemoralis is published by Yin, Ji & Zhou (2021).[52]

- A study on the anatomy of the skull of the holotype specimen of Besanosaurus leptorhynchus, description of additional specimens from the Middle Triassic Besano Formation (Italy/Switzerland) and a study on the phylogenetic relationships of this species is published by Bindellini et al. (2021), who interpret Mikadocephalus gracilirostris as a junior synonym of B. leptorhynchus.[53]

- New stenopterygiid ichthyosaur fossils, representing some of the best preserved Toarcian specimens from Europe (including a specimen with possible soft tissue preservation), are described from south-east France by Martin et al. (2021), who also attempt to determine the causes of the state of preservation of the studied specimens, and evaluate the implications of the study site for the knowledge of the environmental perturbations associated with the Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event.[54]

- A specimen of Ichthyosaurus belonging or related to the species I. communis is identified from the Sinemurian Coimbra Formation (Portugal) by Sousa & Mateus (2021), representing the southernmost occurrence of Ichthyosaurus reported to date.[55]

- A study on the anatomy of narial structures in Early Jurassic ichthyosaurs, and on their implications for the knowledge of the evolution of the bony subdivision of the external naris in more derived ichthyosaurs, is published by Massare, Wahl & Lomax (2021).[56]

- The first unambiguous ichthyosaur remains from Antarctica reported to date are described from the Upper Jurassic Ameghino (=Nordenskjöld) Formation by Campos et al. (2021), who also revise remains of two ichthyosaur specimens from the Upper Jurassic of Madagascar, and describe a third specimen which is the most complete ichthyosaur from this region of Gondwanaland.[57]

- A study aiming to determine whether Cretaceous ichthyosaur remains from Australia can be attributed to the species Platypterygius australis on the basis of vertebral data alone is published by Vakil, Webb & Cook (2021).[58]

Sauropterygians

[edit]New taxa

[edit]| Name | Novelty | Status | Authors | Age | Type locality | Location | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Disputed |

Noè & Gómez-Pérez |

Early Cretaceous (Aptian and Albian) |

A pliosaurid, described after specimens described as Kronosaurus queenlandicus other than fragmentary holotype. Genus includes new species E. longmani. Some later researches criticized the reassignments.[60][61] |

| |||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Campbell et al. |

An elasmosaurid plesiosaur. The type species is F. sloanae. |

| ||||

|

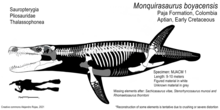

Gen. et comb. nov |

Valid |

Noè & Gómez-Pérez |

Early Cretaceous |

A pliosaurid; a new genus for "Kronosaurus" boyacensis Hampe (1992). |

| |||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Puértolas-Pascual et al. |

An early member of Plesiosauroidea. The type species is P. moelensis. |

| ||||

| Wumengosaurus rotundicarpus[64] | Sp. nov | Valid | Qin et al. | Middle Triassic (Anisian) | A possible pachypleurosaur; a species of Wumengosaurus. |

Research

[edit]- A study on the anatomy and replacement pattern of teeth in Henodus chelyops is published by Pommery et al. (2021).[65]

- A large teeth-bearing dentary of an eosauropterygian of uncertain phylogenetic placement, probably related to the enigmatic Lamprosauroides goepperti, is described from the Lower Muschelkalk (Anisian, Middle Triassic) of Winterswijk (Netherlands) by Spiekman & Klein (2021).[66]

- A study on the bone histology and possible affinities of Proneusticosaurus silesiacus is published by Klein & Surmik (2021).[67]

- Description of a new specimen of Panzhousaurus rotundirostris from the Guanling Formation (Guizhou, China), providing new information on the anatomy of this reptile, and a study on the phylogenetic relationships of this species is published by Lin et al. (2021).[68]

- New specimen of Diandongosaurus, belonging or related to the species D. acutidentatus (though approximately three times larger than the holotype of that species) and lacking most of the right hindlimb, is described from the Anisian Guanling Formation (China) by Liu et al. (2021), who interpret the right hindlimb of this specimen as likely amputated in an attack by an unknown hunter.[69]

- The remains of an indeterminate plesiosaur are reported from the Hauterivian Katterfeld Formation (Chile) by Poblete-Huanca et al. (2021), representing the first record of a Lower Cretaceous plesiosaur from Chile.[70]

- A tooth crown of a pliosaurid belonging to the subfamily Brachaucheninae is described from the Cenomanian La Luna Formation (Venezuela) by Bastiaans et al. (2021), representing the most recent record of a pliosaurid from South America reported to date.[71]

- A study aiming to reconstruct the musculature of limbs of Cryptoclidus eurymerus is published by Krahl & Witzel (2021).[72]

- A study on the postcranial materials of xenopsarian plesiosaurs from the Eromanga Basin (Australia), aiming to determine the utility of vertebral analysis for differentiating and/or grouping Australian plesiosaur specimens, is published by Vakil, Webb & Cook (2021).[73]

- Marx et al. (2021) describe a new specimen of Cardiocorax mukulu from the Maastrichtian Mocuio Formation (Angola), including the most complete plesiosaur skull from sub-Saharan Africa reported to date, and evaluate the implications of this specimen for the knowledge of the anatomy and phylogenetic relationships of this plesiosaur.[74]

- Redescription of the anatomy of the skull of Thalassomedon haningtoni, and a study on the phylogenetic relationships of this species, is published by Sachs et al. (2021).[75]

- Description of one of the earliest quarried elasmosaurid specimens from the Campanian–Maastrichtian strata of Antarctica, identified as a non-aristonectine elasmosaurid belonging to the group Weddellonectia, and a study on the evolution of dorsal vertebral count in members of Weddellonectia, is published by O’Gorman, Aspromonte & Reguero (2021).[76]

- New information of the skeletal anatomy of Alexandronectes zealandiensis is provided by O'Gorman et al. (2021).[77]

- The most complete specimen of Kawanectes lafquenianum reported to date, providing new information on the anatomy of this plesiosaur, is described by O’Gorman (2021).[78]

- Talevi et al. (2021) describe a pathological cervical vertebra of a plesiosaur from the Maastrichtian of Argentina, and interpret this finding as the first record of tuberculosis-like infection in a plesiosaur reported to date.[79]

Turtles

[edit]New taxa

[edit]| Name | Novelty | Status | Authors | Age | Type locality | Location | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sp. nov |

Valid |

Hirayama et al. |

| |||||

| Akoranemys[81] | Gen. et sp. nov | In press | Pérez-García | Late Cretaceous (Cenomanian) | A member of the family Bothremydidae belonging to the tribe Bothremydini and subtribe Bothremydina. Genus includes new species A. madagasika. | |||

|

Gen. et comb. nov |

Valid |

Pérez-García |

A member of the family Podocnemididae belonging to the subfamily Erymnochelyinae. The type species is "Podocnemis" aegyptiaca Andrews (1900). |

|||||

|

Sp. nov |

Valid |

Agnolin |

Middle Pleistocene |

A tortoise, a species of Chelonoidis. |

||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

In press |

Maniel, de la Fuente & Canale |

Late Cretaceous (Cenomanian) |

A member of the family Bothremydidae belonging to the tribe Cearachelyini. Genus includes new species E. pritchardi. |

||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

De Lapparent de Broin, Breton & Rioult |

A member of the family Plesiochelyidae. Genus includes new species G. lennieri. |

|||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Bourque |

A member of the family Geoemydidae. The type species is N. oglala. |

|||||

|

Sp. nov |

Valid |

Lyson et al. |

A member of the family Baenidae. |

|||||

|

Sp. nov |

Valid |

Lyson, Petermann & Miller |

A soft-shelled turtle. |

|||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Adrian et al. |

Late Cretaceous (Cenomanian) |

A member of the family Bothremydidae. The type species is P. appalachius. |

||||

|

Sp. nov |

In press |

Pérez-García et al. |

Jurassic-Cretaceous transition |

|||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Joyce et al. |

Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) |

A member of Pleurodira belonging to the group Pelomedusoides. The type species is S. mailakavava. |

| |||

|

Gen. et comb. nov |

Valid |

Pérez-García |

A member of the family Podocnemididae belonging to the subfamily Erymnochelyinae. The type species is "Podocnemis" fajumensis Andrews (1903). |

| ||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Lapparent de Broin et al. |

A member of the family Bothremydidae. The type species is S. ragei. |

|||||

| Yakemys[93] | Gen. et sp. nov | Tong et al. | Early Cretaceous | Phu Kradung Formation | A member of Macrobaenidae. The type species is Y. multiporcata. |  |

Research

[edit]- A study on the evolution of the organization and composition of the turtle shell is published by Cordero & Vlachos (2021).[94]

- A study on turtle forelimb morphometrics, their relationship to habitat type, and their implications for the knowledge of habitat preferences of fossil turtles, is published by Dudgeon et al. (2021).[95]

- A study on the morphology of the skeleton of Chinlechelys tenertesta, and on its implications for the knowledge of the origin of turtles, is published by Lichtig & Lucas (2021), who reject the interpretation of Eunotosaurus africanus and Pappochelys rosinae as stem-turtles.[96]

- A study on the histology of the carapace and limb bones of Araripemys barretoi, and on the relation between shell microstructure and lifestyle of this turtle, is published by Sena et al. (2021).[97]

- Revision of the Cretaceous bothremydid "Polysternon" atlanticum is published by Pérez-García, Ortega & Murelaga (2021), who consider this taxon to be the senior synonym of Iberoccitanemys convenarum, resulting in a new combination Iberoccitanemys atlanticum.[98]

- Reconstruction of the skull and neuroanatomical structures of Tartaruscola teodorii is presented by Martín-Jiménez & Pérez-García (2021).[99]

- New fossil material of Stupendemys geographica and Caninemys tridentata is described from the Miocene La Victoria Formation (Colombia) by Cadena et al. (2021), who reestablish the validity of C. tridentata as a taxon distinct from S. geographica, and evaluate the implications of the studied fossils for the knowledge of the changes in the shell and scutes during the ontogeny in S. geographica.[100]

- Redescription and a study on the phylogenetic relationships of Uluops uluops is published by Rollot, Evers & Joyce (2021).[101]

- Redescription of the anatomy of the skull of Arundelemys dardeni is published by Evers, Rollot & Joyce (2021).[102]

- A study on the morphological variability in the shell of Pleurosternon bullockii is published by Guerrero & Pérez-García (2021).[103]

- A study on the ontogenetic development of Pleurosternon bullockii, based on data from small specimens from the Berriasian Purbeck Limestone Group (United Kingdom), is published by Guerrero & Pérez-García (2021).[104]

- New fossil material of Plesiochelys is described from the Upper Jurassic (Tithonian) of the Lusitanian Basin (Portugal) by Pérez-García & Ortega (2021), who also revise the Oxfordian species "Hispaniachelys" prebetica and transfer it to the genus Plesiochelys, making it the oldest representative of this genus reported to date.[105]

- Two specimens of thalassochelydian turtles, including a partial hindlimb with well-preserved remains of skin and a large, articulated skeleton of Thalassemys bruntrutana, documenting the presence of particularly elongate forelimbs in this turtle, are described from the Upper Jurassic of Germany by Joyce, Mäuser & Evers (2021), who interpret these specimens as providing evidence of presence of highly keratinized and partially stiffened flippers in some Late Jurassic turtles, structurally similar to those of extant sea turtles.[106]

- A study on the skeletal anatomy of Manchurochelys manchoukuoensis, based on data from a new specimens from the Lower Cretaceous Yixian Formation (China), is published by Li, Zhou & Rabi (2021).[107]

- A large, thick-shelled turtle egg, preserving an embryo of a nanhsiungchelyid possibly belonging to the species Yuchelys nanyangensis, is described from the Upper Cretaceous Xiaguan Formation (China) by Ke et al. (2021).[108]

- An upper Miocene to lower Pliocene carettochelyid fossil, representing the southernmost record of this group reported to date, is described from Beaumaris (Victoria, Australia) by Rule et al. (2021), who interpret this finding and a discontinuous record of soft-shell turtles in the Cenozoic of Queensland as evidence of at least two colonizations of Australia by Trionychia, pre-dating the extant pig-nosed turtle.[109]

- Georgalis (2021) describes a large costal of a soft-shelled turtle from the Eocene of Mali, representing the first record of pan-trionychid turtles from the Paleogene of Africa reported to date.[110]

- New specimens of the tortoises Hadrianus majusculus and H. corsoni and geoemydids Echmatemys haydeni and E. naomi, including skull and juvenile material, and providing new information on the morphology, intraspecific variation and ontogeny of these turtles, are described from the Eocene Willwood Formation and Green River Formation (Wyoming, United States) by Lichtig, Lucas & Jasinski (2021).[111]

- A study on the phylogenetic relationships of Eocene geoemydids "Ocadia" kehreri and "Ocadia" messeliana from the Messel pit (Germany) is published by Ascarrunz, Claude & Joyce (2021).[112]

- Description of new fossil material of Bridgeremys pusilla from the Uinta Formation (Utah, United States), and a study on the differences in morphology of the shell and likely ecology of B. pusilla and two coeval species of Echmatemys, is published by Adrian et al. (2021).[113]

- A study on the phylogenetic relationships and evolutionary history of the tortoise Chelonoidis alburyorum from The Bahamas, based on data from nearly complete mitochondrial genomes, is published by Kehlmaier et al. (2021).[114]

- A study on the identity of the type material of Centrochelys atlantica, based on data from ancient DNA, is published by Kehlmaier et al. (2021), who identify this material as belonging to a specimen of the red-footed tortoise, leaving the Quaternary tortoise known from fossils excavated on the Sal Island in the 1930s without a scientific name.[115]

- A well-preserved humerus a of giant turtle, representing the first known record of gigantic Mesozoic sea turtles in Africa, is described from the Maastrichtian Dakhla Formation (Egypt) by Abu El-Kheir, AbdelGawad & Kassab (2021).[116]

- New specimen of Euclastes wielandi is described from the Paleocene (Danian) Hornerstown Formation (New Jersey, United States) by Ullmann & Carr (2021), who interpret this specimen as proving that E. wielandi is a senior synonym of Catapleura repanda, and study the phylogenetic relationships of E. wielandi.[117]

- A hard-shelled sea turtle specimen, preserved with vestigial soft tissues and likely with incompletely healed bite marks inflicted by a crocodylian or another large-sized seagoing tetrapod, is described from the Eocene (Ypresian) Fur Formation (Denmark) by De La Garza et al. (2021).[118]

Archosauriformes

[edit]Archosaurs

[edit]Other archosauriforms

[edit]New taxa

[edit]| Name | Novelty | Status | Authors | Age | Type locality | Location | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Ezcurra, Bandyopadhyay & Gower |

A member of the family Erythrosuchidae. The type species is B. tapani. |

|||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Dalla Vecchia |

Middle Triassic (Anisian) |

A member of Archosauriformes of uncertain phylogenetic placement, possibly a basal archosauriform, basal phytosaur or a suchian archosaur. The type species is H. boboi. |

| |||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Yáñez et al. |

Late Triassic |

An archosauriform (possibly an archosaur) of uncertain phylogenetic placement. The type species is I. longicollum. |

| |||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Nesbitt et al. |

A dome-headed archosauriform closely related to Triopticus, with which it forms the new clade Protopyknosia. The type species is K. kuttyi. |

|||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Heckert et al. |

A short-faced archosauriform of uncertain affinity, possibly an early-diverging crocodylomorph. The type species is S. sucherorum. |

Research

[edit]- A study on the femoral shape variation and on the relationship between femoral morphology and locomotor habits in early archosaurs and non-archosaur archosauriforms is published by Pintore et al. (2021).[124]

- Fossil material of a member of the genus Doswellia belonging or related to the species D. kaltenbachi is described from the Upper Triassic Chinle Formation (Arizona, United States) by Parker et al. (2021), who interpret this finding as evidence of biogeographic links between the vertebrate assemblage from the Chinle Formation and other Late Triassic assemblages from Texas and Virginia.[125]

- A study on bone histology of proterochampsid specimens from the Triassic Chañares Formation (Argentina), aiming to infer history traits related to growth dynamics, ontogenetic changes, dermal armor histogenesis and lifestyle, is published by Ponce et al. (2021).[126]

- A large phytosaur specimen likely belonging to the species Smilosuchus gregorii, preserved with evidence of pathologies evoking aspects of both osteomyelitis and hypertrophic osteopathy, is described from Norian strata near St. Johns (Arizona, United States) by Heckert, Viner & Carrano (2021).[127]

- A study on the enamel microstructure of phytosaur teeth from western and eastern North American localities, evaluating their implications for the knowledge of biogeographic distributions and ecology of phytosaurs, is published by Hoffman, Miller-Camp & Heckert (2021).[128]

Other reptiles

[edit]New taxa

[edit]| Name | Novelty | Status | Authors | Age | Type locality | Location | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Matamales-Andreu et al. |

A moradisaurine captorhinid. Genus includes new species B. bombardensis. |

|||||

|

Sp. nov |

Rowe et al. |

Permian (Cisuralian) |

||||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Ezcurra et al. |

A rhynchosaur. Genus includes new species E. carrolli. |

|||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Cisneros et al. |

A member of the family Acleistorhinidae. Genus includes new species K. fortunata. |

|||||

| Mengshanosaurus[133] | Gen. et sp. nov | Valid | Meng et al. | Early Cretaceous (Berriasian-Valanginian) | Mengyin Formation | A choristodere belonging to Neochoristodera, the type species is M. minimus. | ||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Chambi-Trowell et al. |

Late Triassic (Norian) |

An early eusphenodontian rhynchocephalian. Genus includes new species M. bonapartei. |

| |||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Pinheiro, Silva-Neves & Da-Rosa |

A procolophonid parareptile. Genus includes new species O. insolitus. |

|||||

|

Gen. et comb. nov |

Valid |

Albright, Sumida & Jung |

Early Permian |

A captorhinid. Genus includes "Captorhinikos" parvus Olson (1970). |

| |||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Villa et al. |

Late Jurassic (Kimmeridgian) |

A rhynchocephalian belonging to the family Sphenodontidae. The type species is S. velserae. |

| |||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Sobral, Sues & Schoch |

A diapsid reptile of uncertain phylogenetic placement. Genus includes new species S. mohli. |

|||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Martínez et al. |

Late Triassic |

A stem-lepidosaur. Genus includes new species T. alcoberi. |

| |||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Apesteguía, Garberoglio & Gómez |

Late Cretaceous (Cenomanian) |

A sphenodontine sphenodontid. Genus includes new species T. giacchinoi. |

||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Kligman et al. |

Late Triassic (Norian) |

A rhynchocephalian belonging to the group Opisthodontia. Genus includes new species T. purgatorii. |

||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Sues & Kligman |

Late Triassic (Carnian) |

Vinita Formation |

A member of Lepidosauromorpha. Genus includes new species V. lizae. |

Research

[edit]- Revision of putative Carboniferous reptile tracks, evaluating their implications for the knowledge of the evolution of locomotor capabilities of putative trackmakers and of the biogeography of the earliest reptiles, is published by Marchetti et al. (2021), who interpret Hylopus hardingi as tracks probably produced by anamniote reptiliomorphs.[143]

- Footprints of early reptiles, including footprints representing the ichnotaxon Notalacerta missouriensis and footprints possibly belonging to the ichnogenus Notalacerta, are described from the Meisenheim, Tambach, Sulzbach and Standenbühl formations (Pennsylvanian and Cisuralian, Germany) by Marchetti et al. (2021), potentially extending the European record of the ichnogenus Notalacerta back to the Moscovian.[144]

- Revision of diagnostic characters used to identify mesosaur species is published by Piñeiro et al. (2021), who report that they could not find unambiguous autapomorphies that characterized Brazilosaurus or Stereosternum.[145]

- Redescription of the holotype and description of the second known specimen of Eudibamus cursoris, providing new information on the skeletal anatomy and locomotor abilities of this reptile, is published by Berman et al. (2021).[146]

- A study on the anatomy of the skull of Nochelesaurus alexanderi is published by Van den Brandt et al. (2021).[147]

- A study on the anatomy of the postcranial skeletons of Bradysaurus baini, Embrithosaurus schwarzi and Nochelesaurus alexanderi is published by van den Brandt et al. (2021).[148]

- A study on the skeletal anatomy and phylogenetic relationships of Provelosaurus americanus, based on data from new fossils and a review of the previously described material, is published by Cisneros, Dentzien-Dias & Francischini (2021).[149]

- Romano et al. (2021) provide a body mass estimate of Scutosaurus karpinskii.[150]

- Tetrapod footprints assigned to the ichnogenus Hyloidichnus, produced by captorhinids or similar reptiles and providing new information on the locomotion of these reptiles, are described from the Permian Pelitic Formation of Gonfaron (Le Luc Basin, Var, France) by Logghe et al. (2021).[151]

- Description of a new specimen of Anthracodromeus longipes from the Carboniferous Allegheny Group (Ohio, United States), preserving an ungual-bearing manus and pedes, and a study on the locomotor ecology of this reptile is published by Mann et al. (2021).[152]

- Partial ilium of a non-archosauromorph neodiapsid reptile is described from the upper Panchet Formation (India) by Ezcurra, Bandyopadhyay & Sen (2021), expanding known diversity of Early Triassic reptiles from this formation.[153]

- A study on the skeletal anatomy, gliding apparatus and phylogenetic relationships of Weigeltisaurus jaekeli, based on data from a nearly complete skeleton from the Upper Permian Kupferschiefer (Germany), is published by Pritchard et al. (2021).[154]

- Redescription of the anatomy of the skull of Coelurosauravus elivensis is published by Buffa et al. (2021).[155]

- A study on the anatomy and phylogenetic relationships of Paliguana whitei is published by Ford et al. (2021).[156]

- A study on the anatomy and phylogenetic relationships of Marmoretta oxoniensis is published by Griffiths et al. (2021).[157]

- Putative choristoderan maxilla from the Bathonian Peski locality (Moskvoretskaya Formation; Moscow Oblast, Russia) is reinterpreted as a fossil a member of Lepidosauromorpha similar to Fraxinisaura and Marmoretta by Skutschas et al. (2021), who interpret this specimens as the first known record of basal lepidosauromorphs in the Middle Jurassic of European Russia.[158]

- Choristoderan vertebrae, representing the first record of choristoderans from the Upper Cretaceous of Asia reported to date, are described from the Turonian Tamagawa Formation (Japan) by Matsumoto et al. (2021).[159]

- New fossil material of neochoristoderes, representing the first known record of this group from the Atlantic coastal plain, is described from the latest Cretaceous of the Navesink Formation and the Ellisdale Fossil Site (New Jersey, United States) by Dudgeon et al. (2021), who also attempt to determine possible causes of the apparent rarity of neochoristoderes in Appalachia.[160]

- A study comparing cervical morphology and neck mobility in Champsosaurus, Simoedosaurus and extant gharial, and evaluating their implications for the knowledge of the feeding behaviour of choristoderans, is published by Matsumoto, Fujiwara & Evans (2021).[161]

- A study on the phylogenetic relationships of archosauromorph reptiles, aiming to determine the relationships of "protorosaurs", is published by Spiekman, Fraser & Scheyer (2021), who name a new clade Dinocephalosauridae.[162]

- A study on the evolution of the morphological diversity of late Permian to Late Jurassic archosauromorph reptiles is published by Foth, Sookias & Ezcurra (2021).[163]

- A study on the evolution of body size of archosauromorph reptiles during the first 90 million years of their evolutionary history is published by Pradelli, Leardi & Ezcurra (2021).[164]

- Revision and a study on the phylogenetic affinities of Malerisaurus is published by Nesbitt et al. (2021), who interpret this reptile as an early diverging, but late-surviving, carnivorous member of Azendohsauridae.[165]

- Revision and a study on the phylogenetic relationships of Eifelosaurus triadicus is published by Sues, Ezcurra & Schoch (2021).[166]

- A study on patterns of neurocentral suture closure in the vertebrae of hyperodapedontine rhynchosaurs during their ontogeny, evaluating their implications for the knowledge of the evolution of patterns of neurocentral suture closure in archosauromorph reptiles and most likely ancestral condition in archosaurs, is published by Heinrich et al. (2021).[167]

- A study on the anatomy of the skull of the holotype specimen of Hyperodapedon sanjuanensis is published by Gentil & Ezcurra (2021).[168]

Reptiles in general

[edit]- A study comparing species richness of synapsids and reptiles during the Pennsylvanian and Cisuralian, evaluating the impact of the preservation biases, of the effect of Lagerstätten, and of contested phylogenetic placement of late Carboniferous and early Permian tetrapods on estimates of relative diversity patterns of synapsids and reptiles, is published by Brocklehurst (2021), who interprets his findings as challenging the assumption that synapsids dominated during the Pennsylvanian and Cisuralian.[169]

- A study on the evolution of the feeding apparatus in early amniotes, aiming to quantify variation in evolutionary rates and constraints during early diversification of amniotes, is published by Brocklehurst & Benson (2021).[170]

- A study comparing the morphology of the maxillary canal of Heleosaurus scholtzi, Varanosaurus acutrostris, Orovenator mayorum and Prolacerta broomi, and evaluating the implications of the morphology of the maxillary canal for the knowledge of the phylogenetic placement of varanopids, is published by Benoit et al. (2021).[171]

- Fischer, Weis & Thuy (2021) describe new ichthyosaur and plesiosaur fossils from successive geological formations in Belgium and Luxembourg spanning the Lower–Middle Jurassic transition, and evaluate the implications of these fossils for the knowledge of the evolution of marine reptile assemblages across the Early–Middle Jurassic transition.[172]

- A study on rates of morphological evolution in the evolutionary history of squamates and rhynchocephalians is published by Herrera-Flores et al. (2021).[173]

References

[edit]- ^ Rage, J.-C.; Adaci, M.; Bensalah, M.; Mahboubi, M.; Marivaux, L.; Mebrouk, F.; Tabuce, R. (2021). "Latest Early-early Middle Eocene deposits of Algeria (Glib Zegdou, HGL50), yield the richest and most diverse fauna of amphibians and squamate reptiles from the Palaeogene of Africa" (PDF). Palæovertebrata. 44 (1): e1. doi:10.18563/pv.44.1.e1. S2CID 233892725.

- ^ Scarpetta, S. G. (2021). "Iguanian lizards from the Split Rock Formation, Wyoming: exploring the modernization of the North American lizard fauna". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 19 (3): 221–251. Bibcode:2021JSPal..19..221S. doi:10.1080/14772019.2021.1894612. S2CID 233402435.

- ^ Willman, A. J.; Konishi, T.; Caldwell, M. W. (2021). "A new species of Ectenosaurus (Mosasauridae: Plioplatecarpinae) from western Kansas, USA, reveals a novel suite of osteological characters for the genus". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 58 (9): 741–755. Bibcode:2021CaJES..58..741W. doi:10.1139/cjes-2020-0175.

- ^ Scarpetta, S. G.; Ledesma, D. T.; Bell, C. J. (2021). "A new extinct species of alligator lizard (Squamata: Elgaria) and an expanded perspective on the osteology and phylogeny of Gerrhonotinae". BMC Ecology and Evolution. 21 (1): Article number 184. doi:10.1186/s12862-021-01912-8. PMC 8482661. PMID 34587907.

- ^ Jurestovsky, D. J. (2021). "Small Colubroids from the Late Hemphillian Gray Fossil Site of Northeastern Tennessee". Journal of Herpetology. 55 (4): 422–431. doi:10.1670/21-008. S2CID 240093403.

- ^ Bochaton, C.; Charles, L.; Lenoble, A. (2021). "Historical and fossil evidence of an extinct endemic species of Leiocephalus (Squamata: Leiocephalidae) from the Guadeloupe Islands" (PDF). Zootaxa. 4927 (3): 383–409. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4927.3.4. PMID 33756701. S2CID 232337806.

- ^ Ikeda, T.; Ota, H.; Tanaka, T.; Ikuno, K.; Kubota, K.; Tanaka, K.; Saegusa, H. (2021). "A fossil Monstersauria (Squamata: Anguimorpha) from the Lower Cretaceous Ohyamashimo Formation of the Sasayama Group in Tamba City, Hyogo Prefecture, Japan". Cretaceous Research. 130: Article 105063. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2021.105063. ISSN 0195-6671. S2CID 239230916.

- ^ Bolet, A.; Stanley, E. L.; Daza, J. D.; Arias, J. S.; Čerňanský, A.; Vidal-García, M.; Bauer, A. M.; Bevitt, J. J.; Peretti, A.; Evans, S. E. (2021). "Unusual morphology in the mid-Cretaceous lizard Oculudentavis". Current Biology. 31 (15): 3303–3314.e3. Bibcode:2021CBio...31E3303B. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.05.040. hdl:11336/148383. PMID 34129826.

- ^ Smith, K. T.; Scanferla, A. (2021). "More than one large constrictor snake lurked around paleolake Messel". Palaeontographica Abteilung A. 323 (1–3): 75–103. doi:10.1127/pala/2021/0119. S2CID 245089117.

- ^ a b Georgalis, G. L.; Čerňanský, A.; Klembara, J. (2021). "Osteological atlas of new lizards from the Phosphorites du Quercy (France), based on historical, forgotten, fossil material". Geodiversitas. 43 (9): 219–293. doi:10.5252/geodiversitas2021v43a9.

- ^ Martinelli, A. G.; Agnolín, F.; Ezcurra, M. D. (2021). "Unexpected new lizard from the Late Cretaceous of southern South America sheds light on Gondwanan squamate diversity". Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales. Nueva Series. 23 (1): 57–80. doi:10.22179/REVMACN.23.716. hdl:11336/167951. S2CID 243557642.

- ^ Smith, K. T.; Habersetzer, J. (2021). "The anatomy, phylogenetic relationships, and autecology of the carnivorous lizard "Saniwa" feisti Stritzke, 1983 from the Eocene of Messel, Germany". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 20 (23): 441–506. doi:10.5852/cr-palevol2021v20a23.

- ^ Georgalis, G. L.; Rabi, M.; Smith, K. T. (2021). "Taxonomic revision of the snakes of the genera Palaeopython and Paleryx (Serpentes, Constrictores) from the Paleogene of Europe". Swiss Journal of Palaeontology. 140 (1): Article 18. Bibcode:2021SwJP..140...18G. doi:10.1186/s13358-021-00224-0.

- ^ Longrich, N. R.; Bardet, N.; Khaldoune, F.; Khadiri Yazami, O.; Jalil, N.-E. (2021). "Pluridens serpentis, a new mosasaurid (Mosasauridae: Halisaurinae) from the Maastrichtian of Morocco and implications for mosasaur diversity" (PDF). Cretaceous Research. 126: Article 104882. Bibcode:2021CrRes.12604882L. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2021.104882.

- ^ Thorn, K. M.; Hutchinson, M. N.; Lee, M. S. Y.; Brown, N. J.; Camens, A. B.; Worthy, T. H. (2021). "A new species of Proegernia from the Namba Formation in South Australia and the early evolution and environment of Australian egerniine skinks". Royal Society Open Science. 8 (2): 201686. Bibcode:2021RSOS....801686T. doi:10.1098/rsos.201686. ISSN 2054-5703. PMC 8074667. PMID 33972861.

- ^ Wagner, P.; Stanley, E. L.; Daza, J. D.; Bauer, A. M. (2021). "A new agamid lizard in mid-Cretaceous amber from northern Myanmar". Cretaceous Research. 124: Article 104813. Bibcode:2021CrRes.12404813W. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2021.104813. S2CID 233704307.

- ^ Smith, K. T.; Scanferla, A. (2021). "A nearly complete skeleton of the oldest definitive erycine boid (Messel, Germany)". Geodiversitas. 43 (1): 1–24. doi:10.5252/geodiversitas2021v43a1.

- ^ Suarez, C. A.; Frederickson, J.; Cifelli, R. L.; Pittman, J. G.; Nydam, R. L.; Hunt-Foster, R. K.; Morgan, K. (2021). "A new vertebrate fauna from the Lower Cretaceous Holly Creek Formation of the Trinity Group, southwest Arkansas, USA". PeerJ. 9: e12242. doi:10.7717/peerj.12242. PMC 8542373. PMID 34721970.

- ^ Longrich, N. R.; Bardet, N.; Schulp, A. S.; Jalil, N.-E. (2021). "Xenodens calminechari gen. et sp. nov., a bizarre mosasaurid (Mosasauridae, Squamata) with shark-like cutting teeth from the upper Maastrichtian of Morocco, North Africa" (PDF). Cretaceous Research. 123: Article 104764. Bibcode:2021CrRes.12304764L. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2021.104764. hdl:1874/418727. S2CID 233567615.

- ^ Sharpe, H. S.; Powers, M. J.; Caldwell, M. W. (2024). "Reassessment of Xenodens calminechari with a discussion of tooth morphology in mosasaurs". The Anatomical Record. doi:10.1002/ar.25612.

- ^ Lafuma, F.; Corfe, I. J.; Clavel, J.; Di-Poï, N. (2021). "Multiple evolutionary origins and losses of tooth complexity in squamates". Nature Communications. 12 (1): Article number 6001. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12.6001L. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-26285-w. PMC 8516937. PMID 34650041.

- ^ Herrera-Flores, J. A.; Stubbs, T. L.; Benton, M. J. (2021). "Ecomorphological diversification of squamates in the Cretaceous". Royal Society Open Science. 8 (3): Article ID 201961. Bibcode:2021RSOS....801961H. doi:10.1098/rsos.201961. PMC 8074880. PMID 33959350.

- ^ Gere, K.; Bodor, E. R.; Makádi, L.; Ősi, A. (2021). "Complex food preference analysis of the Late Cretaceous (Santonian) lizards from Iharkút (Bakony Mountains, Hungary)". Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology. 33 (12): 3686–3702. Bibcode:2021HBio...33.3686G. doi:10.1080/08912963.2021.1887862. S2CID 233961106.

- ^ Villaseñor-Amador, D.; Suárez, N. X.; Cruz, J. A. (2021). "Bipedalism in Mexican Albian lizard (Squamata) and the locomotion type in other Cretaceous lizards". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 109: Article 103299. Bibcode:2021JSAES.10903299V. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2021.103299. S2CID 233526155.

- ^ Augé, M. L.; Dion, M.; Phélizon, A. (2021). "The lizard (Reptilia, Squamata) assemblage from the Paleocene of Montchenot (Paris Basin, MP6)". Geodiversitas. 43 (17): 645–661. doi:10.5252/geodiversitas2021v43a17. S2CID 237537775.

- ^ Čerňanský, A.; Singh, N. P.; Patnaik, R.; Sharma, K. M.; Tiwari, R. P.; Sehgal, R. K.; Singh, N. A.; Choudhary, D. (2021). "The Miocene fossil lizards from Kutch (Gujarat), India: a rare window to the past diversity of this subcontinent". Journal of Paleontology. 96: 213–223. doi:10.1017/jpa.2021.85. S2CID 239688746.

- ^ Georgalis, G. L.; Scheyer, T. M. (2021). "Lizards and snakes from the earliest Miocene of Saint-Gérand-le-Puy, France: an anatomical and histological approach of some of the oldest Neogene squamates from Europe". BMC Ecology and Evolution. 21 (1): Article number 144. doi:10.1186/s12862-021-01874-x. PMC 8278609. PMID 34256702.

- ^ Bochaton, C.; Paradis, E.; Bailon, S.; Grouard, S.; Ineich, I.; Lenoble, A.; Lorvelec, O.; Tresset, A.; Boivin, N. (2021). "Large-scale reptile extinctions following European colonization of the Guadeloupe Islands". Science Advances. 7 (21): eabg2111. Bibcode:2021SciA....7.2111B. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abg2111. PMC 8133755. PMID 34138736.

- ^ Scarsbrook, L.; Sherratt, E.; Hitchmough, R. A.; Rawlence, N. J. (2021). "Skeletal variation in extant species enables systematic identification of New Zealand's large, subfossil diplodactylids". BMC Ecology and Evolution. 21 (1): Article number 67. doi:10.1186/s12862-021-01808-7. PMC 8080345. PMID 33906608.

- ^ Wencker, L. C. M.; Tschopp, E.; Villa, A.; Augé, M. L.; Delfino, M. (2021). "Phylogenetic value of jaw elements of lacertid lizards (Squamata: Lacertoidea): a case study with Oligocene material from France". Cladistics. 37 (6): 765–802. doi:10.1111/cla.12460. hdl:2318/1824383. PMID 34841590.

- ^ Tschopp, E.; Napoli, J. G.; Wencker, L. C. M.; Delfino, M.; Upchurch, P. (2021). "How to Render Species Comparable Taxonomic Units Through Deep Time: a Case Study on Intraspecific Osteological Variability in Extant and Extinct Lacertid Lizards". Systematic Biology. 71 (4): 875–900. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syab078. PMID 34605923.

- ^ Palacios-García, S.; Cruzado-Caballero, P.; Casillas, R.; Castillo Ruiz, C. (2021). "Quaternary biodiversity of the giant fossil endemic lizards from the island of El Hierro (Canary Islands, Spain)". Quaternary Science Reviews. 262: Article 106961. Bibcode:2021QSRv..26206961P. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2021.106961. S2CID 236302752.

- ^ Cabezuelo Hernández, T.; Bolet, A.; Torices, A.; Pérez-García, A. (2021). "Identification of a large anguimorph lizard (Reptilia, Squamata) by an articulated hindlimb from the upper Maastrichtian (Upper Cretaceous) of Basturs-1 (Lleida, Spain)". Cretaceous Research. 131: Article 105094. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2021.105094. ISSN 0195-6671. S2CID 244352137.

- ^ Caldwell, M. W.; Simões, T. R.; Palci, A.; Garberoglio, F. F.; Reisz, R. R.; Lee, M. S. Y.; Nydam, R. L. (2021). "Tetrapodophis amplectus is not a snake: re-assessment of the osteology, phylogeny and functional morphology of an Early Cretaceous dolichosaurid lizard". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 19 (13): 893–952. Bibcode:2021JSPal..19..893C. doi:10.1080/14772019.2021.1983044. S2CID 244414151.

- ^ Jiménez-Huidobro, P.; López-Conde, O. A.; Chavarría-Arellano, M. L.; Porras-Múzquiz, H. (2021). "A yaguarasaurine mosasauroid from the upper Cenomanian−lower Turonian of Coahuila, northern Mexico". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 41 (3): e1986516. Bibcode:2021JVPal..41E6516J. doi:10.1080/02724634.2021.1986516. S2CID 244281080.

- ^ Bardet, N.; Desmares, D.; Sánchez-Pellicer, R.; Gardin, S. (2021). "Rediscovery of "Liodon" asiaticum Répelin, 1915, a Mosasaurini (Squamata, Mosasauridae, Mosasaurinae) from the Upper Cretaceous of the vicinity of Jerusalem – Biostratigraphical insights from microfossils". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 20 (20): 351–372. doi:10.5852/cr-palevol2021v20a20.

- ^ Travis Taylor, L.; Minzoni, R. T.; Suarez, C. A.; Gonzalez, L. A.; Martin, L. D.; Lambert, W. J.; Ehret, D. J.; Harrell, T. L. (2021). "Oxygen isotopes from the teeth of Cretaceous marine lizards reveal their migration and consumption of freshwater in the Western Interior Seaway, North America". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 573: Article 110406. Bibcode:2021PPP...57310406T. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2021.110406. S2CID 234799487.

- ^ Kato, T.; Nakajima, Y.; Shiseki, K.; Ando, H. (2021). "Advanced mosasaurs from the Upper Cretaceous Nakaminato Group in Japan". Island Arc. 30 (1). e12431. Bibcode:2021IsArc..30E2431K. doi:10.1111/iar.12431. S2CID 240303333.

- ^ Van Vranken, N. E.; Boyd, C. A. (2021). "The first in situ collection of a mosasaurine from the marine Breien Member of the Hell Creek Formation in south-central North Dakota, USA". PaleoBios. 38: ucmp_paleobios_54460.

- ^ Klein, C. G.; Pisani, D.; Field, D. J.; Lakin, R.; Wills, M. A.; Longrich, N. R. (2021). "Evolution and dispersal of snakes across the Cretaceous-Paleogene mass extinction". Nature Communications. 12 (1): Article number 5335. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12.5335K. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-25136-y. PMC 8440539. PMID 34521829.

- ^ Georgalis, G. L.; Guinot, G.; Kassegne, K. E.; Amoudji, Y. Z.; Johnson, A. K. C.; Cappetta, H.; Hautier, L. (2021). "An assemblage of giant aquatic snakes (Serpentes, Palaeophiidae) from the Eocene of Togo". Swiss Journal of Palaeontology. 140 (1): Article 20. Bibcode:2021SwJP..140...20G. doi:10.1186/s13358-021-00236-w.

- ^ Syromyatnikova, E.; Tesakov, A.; Titov, V. (2021). "Naja romani (Hoffstetter, 1939) (Serpentes: Elapidae) from the late Miocene of the Northern Caucasus: the last East European large cobra". Geodiversitas. 43 (19): 683–689. doi:10.5252/geodiversitas2021v43a19. S2CID 238231298.

- ^ Biton, R.; Bailon, S. (2021). "An African adder (Bitis arietans complex) at Qafzeh Cave, Israel, during the early Late Pleistocene (MIS 5) record". Journal of Quaternary Science. in press. doi:10.1002/jqs.3402. S2CID 245159565.

- ^ Zverkov, N. G.; Grigoriev, D. V.; Wolniewicz, A. S.; Konstantinov, A. G.; Sobolev, E. S. (2021). "Ichthyosaurs from the Upper Triassic (Carnian–Norian) of the New Siberian Islands, Russian Arctic, and their implications for the evolution of the ichthyosaurian basicranium and vertebral column". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 113: 51–74. doi:10.1017/S1755691021000372. S2CID 245153589.

- ^ Fernández, M. S.; Campos, L.; Maxwell, E. E.; Garrido, A. C. (2021). "Catutosaurus gaspariniae, gen. et sp. nov. (Ichthyosauria, Thunnosauria) of the Upper Jurassic of Patagonia and the evolution of the ophthalmosaurids". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 41 (1): e1922427. Bibcode:2021JVPal..41E2427F. doi:10.1080/02724634.2021.1922427. S2CID 236312664.

- ^ Sander, P. M.; Griebeler, E. M.; Klein, N.; Velez Juarbe, J.; Wintrich, T.; Revell, L. J.; Schmitz, L. (2021). "Early giant reveals faster evolution of large body size in ichthyosaurs than in cetaceans". Science. 374 (6575): eabf5787. doi:10.1126/science.abf5787. PMID 34941418. S2CID 245444783.

- ^ Болатовна, Якупова Джамиля; Максутович, Ахмеденов Кажмурат (2021). "НОВЫЙ ВИД KAZAKHSTANOSAURUS EFIMOVI YAKUPOVA ET AKHMEDENOV SP. NOV. (ICHTHYOSAURIA, UNDOROSAURIDAE) ИЗ ВЕРХНЕЮРСКИХ ОТЛОЖЕНИЙ СРЕДНЕГО ПОВОЛЖЬЯ РОССИИ". Ученые записки Казанского университета. Серия Естественные науки. 163 (2): 251–263. ISSN 2542-064X.

- ^ Cortés, Dirley; Maxwell, Erin E.; Larsson, Hans C. E. (2021-11-22). "Re-appearance of hypercarnivore ichthyosaurs in the Cretaceous with differentiated dentition: revision of 'Platypterygius' sachicarum (Reptilia: Ichthyosauria, Ophthalmosauridae) from Colombia". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 19 (14): 969–1002. Bibcode:2021JSPal..19..969C. doi:10.1080/14772019.2021.1989507. ISSN 1477-2019. S2CID 244512087.

- ^ Barrientos-Lara, J. I.; Alvarado-Ortega, J. (2021). "A new ophthalmosaurid (Ichthyosauria) from the Upper Kimmeridgian deposits of the La Casita formation, near Gómez Farías, Coahuila, northern Mexico". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 111: Article 103499. Bibcode:2021JSAES.11103499B. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2021.103499.

- ^ Barrientos-Lara, J. I.; Alvarado-Ortega, J. (2021). "A new Tithonian ophthalmosaurid ichthyosaur from Coahuila in northeastern Mexico". Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology. 45 (2): 203–216. Bibcode:2021Alch...45..203B. doi:10.1080/03115518.2021.1922755. S2CID 236270217.

- ^ Campos, L.; Fernández, M. S.; Herrera, Y.; Garrido, A. (2021). "Morphological disparity in the evolution of the ophthalmosaurid forefin: new clues from the Upper Jurassic of Argentina". Papers in Palaeontology. 7 (4): 1995–2020. Bibcode:2021PPal....7.1995C. doi:10.1002/spp2.1374. S2CID 237770509.

- ^ Yin, Y.; Ji, C.; Zhou, M. (2021). "The anatomy of the palate in Early Triassic Chaohusaurus brevifemoralis (Reptilia: Ichthyosauriformes) based on digital reconstruction". PeerJ. 9: e11727. doi:10.7717/peerj.11727. PMC 8269639. PMID 34268013.

- ^ Bindellini, G.; Wolniewicz, A. S.; Miedema, F.; Scheyer, T. M.; Dal Sasso, C. (2021). "Cranial anatomy of Besanosaurus leptorhynchus Dal Sasso & Pinna, 1996 (Reptilia: Ichthyosauria) from the Middle Triassic Besano Formation of Monte San Giorgio, Italy/Switzerland: taxonomic and palaeobiological implications". PeerJ. 9: e11179. doi:10.7717/peerj.11179. PMC 8106916. PMID 33996277.

- ^ Martin, J. E.; Suan, G.; Suchéras-Marx, B.; Rulleau, L.; Schlögl, J.; Janneau, K.; Williams, M.; Léna, A.; Grosjean, A.-S.; Sarroca, E.; Perrier, V.; Fernandez, V.; Charruault, A.-L.; Maxwell, E. E.; Vincent, P. (2021). "Stenopterygiids from the lower Toarcian of Beaujolais and a chemostratigraphic context for ichthyosaur preservation during the Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event". In M. Reolid; L. V. Duarte; E. Mattioli; W. Ruebsam (eds.). Carbon Cycle and Ecosystem Response to the Jenkyns Event in the Early Toarcian (Jurassic) (PDF). Vol. 514. The Geological Society of London. pp. 153–172. doi:10.1144/SP514-2020-232. S2CID 240424255.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Sousa, J.; Mateus, O. (2021). "The southernmost occurrence of Ichthyosaurus from the Sinemurian of Portugal". Fossil Record. 24 (2): 287–294. Bibcode:2021FossR..24..287S. doi:10.5194/fr-24-287-2021. hdl:10362/131844.

- ^ Massare, J. A.; Wahl, W. R.; Lomax, D. R. (2021). "Narial structures in Ichthyosaurus and other Early Jurassic ichthyosaurs as precursors to a completely subdivided naris". Paludicola. 13 (2): 128–139.

- ^ Campos, L.; Fernández, M. S.; Herrera, Y.; Talevi, M.; Concheyro, A.; Gouiric-Cavalli, S.; O'Gorman, J. P.; Santillana, S. N.; Acosta-Burlaille, L.; Moly, J. J.; Reguero, M. A. (2021). "Bridging the southern gap: First definitive evidence of Late Jurassic ichthyosaurs from Antarctica and their dispersion routes". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 109: Article 103259. Bibcode:2021JSAES.10903259C. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2021.103259. ISSN 0895-9811. S2CID 233714015.

- ^ Vakil, V.; Webb, G. E.; Cook, A. G. (2021). "Can vertebral remains differentiate more than one species of Australian Cretaceous ichthyosaur?". Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology. 44 (4): 537–554. doi:10.1080/03115518.2020.1853809. S2CID 231875679.

- ^ a b Noè, L. F.; Gómez-Pérez, M. (2021). "Giant pliosaurids (Sauropterygia; Plesiosauria) from the Lower Cretaceous peri-Gondwanan seas of Colombia and Australia". Cretaceous Research. 132: Article 105122. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2021.105122.

- ^ Fischer, Valentin; Benson, Roger B J; Zverkov, Nikolay G; Arkhangelsky, Maxim S; Stenshin, Ilya M; Uspensky, Gleb N; Prilepskaya, Natalya E (2023-03-15). "Anatomy and relationships of the bizarre Early Cretaceous pliosaurid Luskhan itilensis". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 198 (1): 220–256. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlac108. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ^ Poropat, Stephen F.; Bell, Phil R.; Hart, Lachlan J.; Salisbury, Steven W.; Kear, Benjamin P. (2023-04-03). "An annotated checklist of Australian Mesozoic tetrapods". Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology. 47 (2): 129–205. doi:10.1080/03115518.2023.2228367. hdl:20.500.11937/96166. ISSN 0311-5518.

- ^ Campbell, J. A.; Mitchell, M. T.; Ryan, M. J.; Anderson, J. S. (2021). "A new elasmosaurid (Sauropterygia: Plesiosauria) from the non-marine to paralic Dinosaur Park Formation of southern Alberta, Canada". PeerJ. 9: e10720. doi:10.7717/peerj.10720. PMC 7882142. PMID 33614274.

- ^ Puértolas-Pascual, E.; Marx, M.; Mateus, O.; Saleiro, A.; Fernandes, A. E.; Marinheiro, J.; Tomás, C.; Mateus, S. (2021). "A new plesiosaur from the Lower Jurassic of Portugal and the early radiation of Plesiosauroidea". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 66 (2): 369–388. doi:10.4202/app.00815.2020. hdl:10362/123694.

- ^ Qin, Yanjiao; He, Xiao; Luo, Yongming; Hu, Xinrui; Jiang, Liangbing; Deng, Xiaojie; Shi, Zhenhua; Ran, Weiyu (2021). "A New Species of Wumengosaurus from Panxian Fauna in Middle Triassic of Guizhou Province". Guizhou Geology (in Literary Chinese). 38 (4): 373–381. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1000-5943.2021.04.004. ISSN 1000-5943.

- ^ Pommery, Y.; Scheyer, T. M.; Neenan, J. M.; Reich, T.; Fernandez, V.; Voeten, D. F. A. E.; Losko, A. S.; Werneburg, I. (2021). "Dentition and feeding in Placodontia: tooth replacement in Henodus chelyops". BMC Ecology and Evolution. 21 (1): Article number 136. doi:10.1186/s12862-021-01835-4. PMC 8256584. PMID 34225664.

- ^ Spiekman, S. N. F.; Klein, N. (2021). "An enigmatic lower jaw from the Lower Muschelkalk (Anisian, Middle Triassic) of Winterswijk provides insights into dental configuration, tooth replacement and histology". Netherlands Journal of Geosciences. 100: e17. Bibcode:2021NJGeo.100E..17S. doi:10.1017/njg.2021.12.

- ^ Klein, N.; Surmik, D. (2021). "Bone histology of eosauropterygian diapsid Proneusticosaurus silesiacus from the Middle Triassic of Poland reveals new insights into taxonomic affinities". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 66 (3): 585–598. doi:10.4202/app.00850.2020.

- ^ Lin, W.-B.; Jiang, D.-Y.; Rieppel, O.; Motani, R.; Tintori, A.; Sun, Z.-Y.; Zhou, M. (2021). "Panzhousaurus rotundirostris Jiang et al., 2019 (Diapsida: Sauropterygia) and the Recovery of the Monophyly of Pachypleurosauridae". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 41 (1): e1901730. Bibcode:2021JVPal..41E1730L. doi:10.1080/02724634.2021.1901730. S2CID 234853964.

- ^ Liu, Q.; Yang, T.; Cheng, L.; Benton, M. J.; Moon, B. C.; Yan, C.; An, Z.; Tian, L. (2021). "An injured pachypleurosaur (Diapsida: Sauropterygia) from the Middle Triassic Luoping Biota indicating predation pressure in the Mesozoic". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): Article number 21818. Bibcode:2021NatSR..1121818L. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-01309-z. PMC 8575933. PMID 34750442.

- ^ Poblete-Huanca, Andrea; Suárez, Manuel; Rubilar-Rogers, David; Gressier, Jean Baptiste; Arraño, Constanza; Ormazábal, Matías (2021). "First record of a Lower Cretaceous (Hauterivian) plesiosaur from Chile". Cretaceous Research. 128: Article number 104963. Bibcode:2021CrRes.12804963P. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2021.104963. ISSN 0195-6671.

- ^ Bastiaans, D.; Madzia, D.; Carrillo-Briceño, J. D.; Sachs, S. (2021). "Equatorial pliosaurid from Venezuela marks the youngest South American occurrence of the clade". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): Article number 15501. Bibcode:2021NatSR..1115501B. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-94515-8. PMC 8322105. PMID 34326353.

- ^ Krahl, A.; Witzel, U. (2021). "Foreflipper and hindflipper muscle reconstructions of Cryptoclidus eurymerus in comparison to functional analogues: introduction of a myological mechanism for flipper twisting". PeerJ. 9: e12537. doi:10.7717/peerj.12537. PMC 8684327. PMID 35003916.

- ^ Vakil, V.; Webb, G.; Cook, A. (2021). "Taxonomic utility of Early Cretaceous Australian plesiosaurian vertebrae". Palaeontologia Electronica. 24 (3): Article number 24.3.a30. doi:10.26879/1095.

- ^ Marx, M. P.; Mateus, O.; Polcyn, M. J.; Schulp, A. S.; Gonçalves, A. O.; Jacobs, L. L. (2021). "The cranial anatomy and relationships of Cardiocorax mukulu (Plesiosauria: Elasmosauridae) from Bentiaba, Angola". PLOS ONE. 16 (8): e0255773. Bibcode:2021PLoSO..1655773M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0255773. PMC 8370651. PMID 34403433.

- ^ Sachs, S.; Lindgren, J.; Madzia, D.; Kear, B. P. (2021). "Cranial osteology of the mid-Cretaceous elasmosaurid Thalassomedon haningtoni from the Western Interior Seaway of North America". Cretaceous Research. 123: Article 104769. Bibcode:2021CrRes.12304769S. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2021.104769. S2CID 234055157.

- ^ O’Gorman, J. P.; Aspromonte, F.; Reguero, M. (2021). "New data on one of the first plesiosaur (Reptilia, Sauropterygia) skeletons recovered from Antarctica, with comments on the dorsal sacral and regions of elasmosaurids". Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology. 45 (3): 354–368. doi:10.1080/03115518.2021.1958378. S2CID 239679057.

- ^ O'Gorman, J. P.; Otero, R. A.; Hiller, N.; O'Keefe, R. F.; Scofield, R. P.; Fordyce, E. (2021). "CT-scan description of Alexandronectes zealandiensis (Elasmosauridae, Aristonectinae), with comments on the elasmosaurid internal cranial features". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 41 (2): e1923310. Bibcode:2021JVPal..41E3310O. doi:10.1080/02724634.2021.1923310. S2CID 237518012.

- ^ O’Gorman, J. P. (2021). "The most complete specimen of Kawanectes lafquenianum (Sauropterygia, Plesiosauria): new data on basicranial anatomy and possible sexual dimorphism in elasmosaurids". Cretaceous Research. 125: Article 104836. Bibcode:2021CrRes.12504836O. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2021.104836.

- ^ Talevi, M.; Rothschild, B. M.; Mitidieri, M.; Fernández, M. S. (2021). "Infectious spondylitis with pathology mimicking that of tuberculosis in a cervical vertebra of a plesiosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of Patagonia, Argentina". Cretaceous Research. 128: Article 104982. Bibcode:2021CrRes.12804982T. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2021.104982.

- ^ Hirayama*, Ren; Sonoda, Teppei; Uno, Hikaru; Horie, Kenji; Tsutsumi, Yukiyasu; Sasaki, Kazuhisa; Takisawa, Shunsuke Mitsuzuka and Toshio (2021). "Adocus Kohaku, A New Species of Aquatic Turtle (Testudines: Cryptodira: Adocidae) from the Late Cretaceous of Kuji, Iwate Prefecture, Northeast Japan, with Special References to the Geological Age of the Tamagawa Formation (Kuji Group) LSID urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:61376EEE-A386-416E-98AE-FF64FE2597A2". International Journal of Paleobiology & Paleontology. 4 (1).

- ^ Pérez-García, A. (2021-02-01). "A new bothremydid turtle (Pleurodira) from the Upper Cretaceous (Cenomanian) of Madagascar". Cretaceous Research. 118: 104645. Bibcode:2021CrRes.11804645P. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104645. ISSN 0195-6671. S2CID 225033660.

- ^ a b Pérez-García, A. (2021). "New shell information and new generic attributions for the Egyptian podocnemidid turtles "Podocnemis" fajumensis (Oligocene) and "Podocnemis" aegyptiaca (Miocene)". Fossil Record. 24 (2): 247–262. Bibcode:2021FossR..24..247P. doi:10.5194/fr-24-247-2021.

- ^ Agnolin, F. L. (2021). "A New Tortoise from the Pleistocene of Argentina with Comments on the Extinction of Late Pleistocene Tortoises and Plant Communities". Paleontological Journal. 55 (8): 913–922. Bibcode:2021PalJ...55..913A. doi:10.1134/S0031030121080037. S2CID 245330393.

- ^ Maniel, I.J.; de la Fuente, M. S.; Zhuo, J.I. (2021). "The first Cearachelyini (Pelomedusoides, Bothremydidae) turtle from the Upper Cretaceous of Patagonia, and an overview of the occurrence and diversity of Pelomedusoides in Patagonia". Cretaceous Research. 125: Article 104869. Bibcode:2021CrRes.12504869M. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2021.104869.

- ^ de Lapparent de Broin, F.; Breton, G.; Rioult, M. (2021). "Mesozoic turtles from Le Havre (France), review, definition of Globochelus lennieri n. g. n. sp. and new data on Tropidemys langii, Plesiochelyidae". Annales de Paléontologie. 107 (1): Article 102447. doi:10.1016/j.annpal.2020.102447. S2CID 234139698.

- ^ Bourque, J. R. (2021). "A new geoemydid (Testudines, aff. Rhinoclemmydinae) from the upper Eocene Chadron Formation (White River Group) of northwestern Nebraska" (PDF). Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History. 58 (5): 86–101. doi:10.58782/flmnh.nlkv7912.

- ^ Lyson, T. R.; Petermann, H.; Toth, N.; Bastien, S.; Miller, I. M. (2021). "A new baenid turtle, Palatobaena knellerorum sp. nov., from the lower Paleocene (Danian) Denver Formation of south-central Colorado, U.S.A.". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 41 (2): e1925558. Bibcode:2021JVPal..41E5558L. doi:10.1080/02724634.2021.1925558. S2CID 237518055.

- ^ Lyson, T. R.; Petermann, H.; Miller, I. M. (2021). "A new plastomenid trionychid turtle, Plastomenus joycei, sp. nov., from the earliest Paleocene (Danian) Denver Formation of south-central Colorado, U.S.A.". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 41 (1): e1913600. Bibcode:2021JVPal..41E3600L. doi:10.1080/02724634.2021.1913600. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 236335666.

- ^ Adrian, B.; Smith, H. F.; Noto, C. R.; Grossman, A. (2021). "An early bothremydid from the Arlington Archosaur Site of Texas". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): Article number 9555. Bibcode:2021NatSR..11.9555A. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-88905-1. PMC 8137945. PMID 34017016.

- ^ Pérez-García, A.; Martín-Jiménez, M.; Aurell, M.; Canudo, J.I.; Casternera, D. (2021). "A new Iberian pleurosternid (Jurassic-Cretaceous transition, Spain) and first neuroanatomical study of this clade of stem turtles". Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology. 34 (2): 298–311. doi:10.1080/08912963.2021.1910818. S2CID 234822940.

- ^ Joyce, W. G.; Rollot, Y.; Evers, S. W.; Lyson, T. R.; Rahantarisoa, L. J.; Krause, D. W. (2021). "A new pelomedusoid turtle, Sahonachelys mailakavava, from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar provides evidence for convergent evolution of specialized suction feeding among pleurodires". Royal Society Open Science. 8 (5): Article ID 210098. Bibcode:2021RSOS....810098J. doi:10.1098/rsos.210098. PMC 8097199. PMID 34035950.

- ^ de Lapparent de Broin, F.; Métais, G.; Bartolini, A.; Brohi, I. A.; Lashari, R. A.; Marivaux, L.; Merle, D.; Warar, M. A.; Solangi, S. H. (2021). "First report of a bothremydid turtle, Sindhochelys ragei n. gen., n. sp., from the early Paleocene of Pakistan, systematic and palaeobiogeographic implications". Geodiversitas. 43 (25): 1341–1363. doi:10.5252/geodiversitas2021v43a25. S2CID 245220767.

- ^ Tong, Haiyan; Chanthasit, Phornphen; Naksri, Wilailuck; Ditbanjong, Pitaksit; Suteethorn, Suravech; Buffetaut, Eric; Suteethorn, Varavudh; Wongko, Kamonlak; Deesri, Uthumporn; Claude, Julien (December 2021). "Yakemys multiporcata n. g. n. sp., a Large Macrobaenid Turtle from the Basal Cretaceous of Thailand, with a Review of the Turtle Fauna from the Phu Kradung Formation and Its Stratigraphical Implications". Diversity. 13 (12): 630. doi:10.3390/d13120630.

- ^ Cordero, G. A.; Vlachos, E. (2021). "Reduction, reorganization and stasis in the evolution of turtle shell elements". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 134 (4): 892–911. doi:10.1093/biolinnean/blab122.

- ^ Dudgeon, T. W.; Livius, M. C. H.; Alfonso, N.; Tessier, S.; Mallon, J. C. (2021). "A new model of forelimb ecomorphology for predicting the ancient habitats of fossil turtles". Ecology and Evolution. 11 (23): 17071–17079. Bibcode:2021EcoEv..1117071D. doi:10.1002/ece3.8345. PMC 8668755. PMID 34938493.

- ^ Lichtig, A. J.; Lucas, S. G. (2021). "Chinlechelys from the Upper Triassic of New Mexico, USA, and the origin of turtles". Palaeontologia Electronica. 24 (1): Article number 24.1.a13. doi:10.26879/886.

- ^ Sena, M. V. A.; Bantim, R. A. M.; Saraiva, A. A. F.; Sayão, J. M.; Oliveira, G. R. (2021). "Shell and long-bone histology, skeletochronology, and lifestyle of Araripemys barretoi (Testudines: Pleurodira), a side-necked turtle of the Lower Cretaceous from Brazil". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 93 (Suppl. 2): e20201606. doi:10.1590/0001-3765202120201606. PMID 34378648. S2CID 236979010.

- ^ Pérez-García, A.; Ortega, F.; Murelaga, X. (2021). "Iberoccitanemys atlanticum (Lapparent de Broin & Murelaga, 1996) n. comb.: new data on the diversity and paleobiogeographic distributions of the Campanian-Maastrichtian bothremydid turtles of Europe". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 20 (32): 667–676. doi:10.5852/cr-palevol2021v20a32. S2CID 238704135.

- ^ Martín-Jiménez, M.; Pérez-García, A. (2021). "Neuroanatomical Study and Three-Dimensional Reconstruction of the Skull of a Bothremydid Turtle (Pleurodira) Based on the European Eocene Tartaruscola teodorii". Diversity. 13 (7): Article 298. doi:10.3390/d13070298.

- ^ Cadena, E.-A.; Link, A.; Cooke, S. B.; Stroik, L. K.; Vanegas, A. F.; Tallman, M. (2021). "New insights on the anatomy and ontogeny of the largest extinct freshwater turtles". Heliyon. 7 (12): e08591. Bibcode:2021Heliy...708591C. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08591. PMC 8717240. PMID 35005268.

- ^ Rollot, Y.; Evers, S. W.; Joyce, W. G. (2021). "A redescription of the Late Jurassic (Tithonian) turtle Uluops uluops and a new phylogenetic hypothesis of Paracryptodira". Swiss Journal of Palaeontology. 140 (1): Article 23. Bibcode:2021SwJP..140...23R. doi:10.1186/s13358-021-00234-y. PMC 8550081. PMID 34721284.

- ^ Evers, S. W.; Rollot, Y.; Joyce, W. G. (2021). "New interpretation of the cranial osteology of the Early Cretaceous turtle Arundelemys dardeni (Paracryptodira) based on a CT-based re-evaluation of the holotype". PeerJ. 9: e11495. doi:10.7717/peerj.11495. PMC 8174147. PMID 34131522.

- ^ Guerrero, A.; Pérez-García, A. (2021). "Morphological variability and shell characterization of the European uppermost Jurassic to lowermost Cretaceous stem turtle Pleurosternon bullockii (Paracryptodira, Pleurosternidae)". Cretaceous Research. 125: Article 104872. Bibcode:2021CrRes.12504872G. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2021.104872.

- ^ Guerrero, A.; Pérez-García, A. (2021). "Ontogenetic development of the European basal aquatic turtle Pleurosternon bullockii (Paracryptodira, Pleurosternidae)". Fossil Record. 24 (2): 357–377. Bibcode:2021FossR..24..357G. doi:10.5194/fr-24-357-2021.

- ^ Pérez-García, A.; Ortega, F. (2021). "New finds of the turtle Plesiochelys in the Upper Jurassic of Portugal and evaluation of its diversity in the Iberian Peninsula". Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology. 34: 121–129. doi:10.1080/08912963.2021.1903000. S2CID 234877934.

- ^ Joyce, W. G.; Mäuser, M.; Evers, S. W. (2021). "Two turtles with soft tissue preservation from the platy limestones of Germany provide evidence for marine flipper adaptations in Late Jurassic thalassochelydians". PLOS ONE. 16 (6): e0252355. Bibcode:2021PLoSO..1652355J. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0252355. PMC 8174742. PMID 34081728.

- ^ Li, L.; Zhou, C.-F.; Rabi, M. (2021). "The skeletal anatomy of Manchurochelys manchoukuoensis (Pan-Cryptodira: Sinemydidae) from the Lower Cretaceous Yixian Formation". Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology. 34 (3): 538–554. doi:10.1080/08912963.2021.1934834. S2CID 238780262.

- ^ Ke, Y.; Wu, R.; Zelenitsky, D. K.; Brinkman, D.; Hu, J.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, H.; Han, F. (2021). "A large and unusually thick-shelled turtle egg with embryonic remains from the Upper Cretaceous of China". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 288 (1957): Article ID 20211239. doi:10.1098/rspb.2021.1239. PMC 8370798. PMID 34403631.

- ^ Rule, J. P.; Kool, L.; Parker, W. M. G.; Fitzgerald, E. M. G. (2021). "Turtles all the way down: Neogene pig-nosed turtle fossil from southern Australia reveals cryptic freshwater turtle invasions and extinctions". Papers in Palaeontology. 8. doi:10.1002/spp2.1414. S2CID 245107305.

- ^ Georgalis, G. L. (2021). "First pan-trionychid turtle (Testudines, Pan-Trionychidae) from the Palaeogene of Africa". Papers in Palaeontology. 7 (4): 1919–1926. Bibcode:2021PPal....7.1919G. doi:10.1002/spp2.1372. S2CID 237910547.

- ^ Lichtig, A. J.; Lucas, S. G.; Jasinski, S. E. (2021). "Complete specimens of the Eocene testudinoid turtles Echmatemys and Hadrianus and the North American origin of tortoises". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 82: 161–174.

- ^ Ascarrunz, E.; Claude, J.; Joyce, W. G. (2021). "The phylogenetic relationships of geoemydid turtles from the Eocene Messel Pit Quarry: a first assessment using methods for continuous and discrete characters". PeerJ. 9: e11805. doi:10.7717/peerj.11805. PMC 8349520. PMID 34430073.

- ^ Adrian, B.; Smith, H. F.; Hutchison, J. H.; Townsend, K. E. B. (2021). "Geometric morphometrics and anatomical network analyses reveal ecospace partitioning among geoemydid turtles from the Uinta Formation, Utah". The Anatomical Record. 305 (6): 1359–1393. doi:10.1002/ar.24792. PMID 34605614. S2CID 238257931.

- ^ Kehlmaier, C.; Albury, N. A.; Steadman, D. W.; Graciá, E.; Franz, R.; Fritz, U. (2021). "Ancient mitogenomics elucidates diversity of extinct West Indian tortoises". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): Article number 3224. Bibcode:2021NatSR..11.3224K. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-82299-w. PMC 7873039. PMID 33564028.

- ^ Kehlmaier, C.; López-Jurado, L. F.; Hernández-Acosta, N.; Mateo-Miras, A.; Fritz, U. (2021). ""Ancient DNA" reveals that the scientific name for an extinct tortoise from Cape Verde refers to an extant South American species". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): Article number 17537. Bibcode:2021NatSR..1117537K. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-97064-2. PMC 8413269. PMID 34475454.

- ^ Abu El-Kheir, G.A.-M.; AbdelGawad, M. K.; Kassab, O. (2021). "First known gigantic sea turtle from the Maastrichtian deposits in Egypt". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 66 (2): 349–355. doi:10.4202/app.00849.2020.

- ^ Ullmann, S. G.; Carr, E. (2021). "Catapleura Cope, 1870 is Euclastes Cope, 1867 (Testudines: Pan-Cheloniidae): synonymy revealed by a new specimen from New Jersey". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 19 (7): 491–517. Bibcode:2021JSPal..19..491U. doi:10.1080/14772019.2021.1928306. S2CID 236504236.

- ^ De La Garza, R. G.; Madsen, H.; Eriksson, M. E.; Lindgren, J. (2021). "A fossil sea turtle (Reptilia, Pan-Cheloniidae) with preserved soft tissues from the Eocene Fur Formation of Denmark". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 41 (3): e1938590. Bibcode:2021JVPal..41E8590G. doi:10.1080/02724634.2021.1938590.

- ^ Ezcurra, M. D.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Gower, D. J. (2021). "A new erythrosuchid archosauriform from the Middle Triassic Yerrapalli Formation of south-central India". Ameghiniana. 58 (2): 132–168. doi:10.5710/AMGH.18.01.2021.3416. S2CID 234217303.

- ^ Dalla Vecchia, F. M. (2021). "Heteropelta boboi n. gen., n. sp. an armored archosauriform (Reptilia: Archosauromorpha) from the Middle Triassic of Italy". PeerJ. 9: e12468. doi:10.7717/peerj.12468. PMC 8601055. PMID 34820195.