User:Ewr27/Shipibo language

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (September 2017) |

| Shipibo-Conibo | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Peru |

| Region | Ucayali Region |

| Ethnicity | Shipibo-Conibo people |

Native speakers | 26,000 (2003)[1] |

Panoan

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | Either:shp – Shipibo-Conibokaq – Tapiche Capanahua |

| Glottolog | ship1253 |

| |

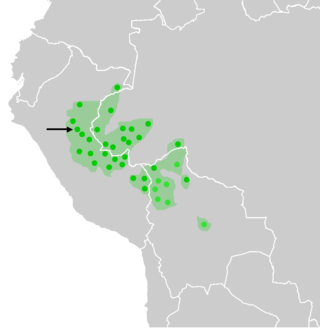

Shipibo (also Shipibo-Conibo, Shipibo-Konibo) is a Panoan language spoken in the Ucayali River Valley, in the Upper Amazon watershed in the central eastern part of Peru. It is also spoken in Boliva and Brazil. A total of roughly 30,000 speakers use Shipibo and it is an officially recognized language of Peru. The language is sometimes also called Shipibo-Conibo or Shipibo-Konibo after the two main previously distinct ethnic groups which form its speakers. [2]

Shipibo is perhaps the best-known Amazonian lowland language to outsiders, because Pucallpa, which is at their centre, is the most accessible point on the Amazon side of Peru. While still endangered, Shipibo-Conibo communities have maintained the culture and language despite several hundred years of contact with Europeans, resisting assimilation efforts, spanish bilingually programs, and highway development which threatened their well-being. [3]

The Shipibo are the descendants of Panoan-speaking people who lived in the northeastern part of Bolivia and southeastern Peru before 300 CE. Since 1791, the area has been under continual contact with missionaries and Spanish-speaking people. Most contemporary Shipibo men and women are bilingual in Spanish and their native language. Still, they maintain a strong ethnic identity and remain culturally distinct from the purely Spanish-speaking population that is now the majority of the area. [4]

Panoan Language Family

[edit]Belonging to the broader family of Panoan languages, Shipibo is the largest and most broadly spoken among the 32 languages to which it is related. A few large, viable Panoan speech communities still exist. Notably, Shipibo-Konibo, and Matses, Kashinawa of the Ibuaçu River, Yaminawa, Kashibo, Marubo, and Chakobo all have 1000 or more speakers. But most other extant Panoan languages are obsolescent or in danger of extinction due to low populations and language replacement by Spanish, Portuguese, or Shipibo-Konibo, and most of these are incompletely described. [4]

Panoan languages have been known by name since the 1600s, their word lists first became publically available in the 1830s, and by the 1940s they began to be topics of academic linguistic studies.[4]

Shipibo Language Endangerment Status

[edit]These early contacts in the late 16th century introduced epidemics and caused significant population shifts. Disease and slave raids continued to stress the indigenous population through the 17th and 18th century. (continuity)

In 2004, processes of change were further accelerated when construction began on the Interoceanic Highway to link Brazil’s Atlantic coast with Peru’s Pacific ports/ Eve before its completion, the highway had major impacts no conservation efforts and indigenous rights. Finished in the fall of 2014, the 2,603-km road is expected to cause unknown and substantial demographic changes, environmental shifts, and further pressures of globalization. It remains to be seen how they will balance their desire to maintain their distinct identity with the changes wrought by the expanding national economic frontier. [5]

Folklore / Mythology in Shipibo Language

[edit]Today as in times past, the river is compared to the great serpent, called Roin in the Shipibo language. It is represented as an icongraphic motif, geometric and schematic, in all the painted artifacts such as ceramic ware; textiles; macanas, or clubs; and other ceremonial ornaments, such as the traditional corona, or crown.

Dialects

[edit]

Shipibo has three attested dialects:

- Shipibo and Konibo (Conibo), which have merged

- Kapanawa of the Tapiche River, which is obsolescent[4]: 18

Extinct Xipináwa (Shipinawa) is thought to have been a dialect as well,[4]: 14 but there is no linguistic data. It is a member of the Panoan family and thus is related to such languages as Capanahua, Amahuaca and Chacobo

Phonology

[edit]Vowels

[edit]

Many Panoan languages have minor instances of vowel harmony, perhaps remnants of historically more general vowel harmony. Shipibo uses a system of four oral vowels, each with a nasalized counterpart. A vowel following a nasal consonant is also nasalized but such vowels have different phonological behavior from underlying nasalized vowels. When two unstressed vowels are adjacent, the second is often deleted. Unstressed vowels may also be devoiced or completely elided between two voiceless obstruents.

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | i ĩ | ɯ ɯ̃ |

| Mid | o õ | |

| Open | a ã |

- /i/ and /o/ are lower than their cardinal counterparts (in addition to being more front in the latter case): [i̞], [o̽], /ɯ/ is more front than cardinal [ɯ]: [ɯ̟], whereas /a/ is more close and more central ([ɐ]) than cardinal [a]. The first three vowels tend to be somewhat more central in closed syllables, whereas /ɯ/ before coronal consonants (especially /n, t, s/) can be as central as [ɨ].[2]: 282–283

- In connected speech, two adjacent vowels may be realized as a rising diphthong.[2]: 283

Nasal

[edit]- The oral vowels /i, ɯ, o, a/ are phonetically nasalized [ĩ, ɯ̃, õ, ã] after a nasal consonant, but the phonological behaviour of these allophones is different from the nasal vowel phonemes /ĩ, ɯ̃, õ, ã/.[2]: 282

- Oral vowels in syllables preceding syllables with nasal vowels are realized as nasal, but not when a consonant other than /w, j/ intervenes.[2]: 283

Unstressed

[edit]- The second one of the two adjacent unstressed vowels is often deleted.[2]: 283

- Unstressed vowels may be devoiced or even elided between two voiceless obstruents.[2]: 283

- Stress must be considered distinctive in Shipibo, although there are strong regularities. For example, in bisyllabic nouns stress regularly falls on the second syllable if that is closed or has an underlying nasalized vowel, otherwise it falls on the first.

Consonants

[edit]| Labial | Dental/ | Retroflex | Palato-alveolar | Dorsal | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | |||||

| Plosive | p | t | k c/qu | ʔ h | |||

| Affricate | ts ts | tʃ ch | |||||

| Fricative | voiceless | s s | ʂ s̈h | ʃ sh | h j | ||

| voiced | β b | ||||||

| Approximant | w hu | ɻ r | j y | ||||

- /m, p, β/ are bilabial, whereas /w/ is labialized velar.

- /β/ is most typically a fricative [β], but other realizations (such as an approximant [β̞], a stop [b] and an affricate [bβ]) also appear. The stop realization is most likely to appear in word-initial stressed syllables, whereas the approximant realization appears most often as onsets to non-initial unstressed syllables.[2]: 282

- /n, ts, s/ are alveolar [n, ts, s], whereas /t/ is dental [t̪].[2]: 281

- The /ʂ–ʃ/ distinction can be described as an apical–laminal one.[2]: 282

- /k/ is velar, whereas /j/ is palatal.[2]: 281

- Before nasal vowels, /w, j/ are nasalized [w̃, j̃] and may be even realized close to nasal stops [ŋʷ, ɲ].[2]: 283

- /w/ is realized as [w] before /a, ã/, as [ɥ] before /i, ĩ/ and as [ɰ] before /ɯ, ɯ̃/. It does not occur before /o, õ/.[2]: 283

- /ɻ/ is a very variable sound:

- Intervocalically, it is realized either as continuant, with or without weak frication ([ɻ] or [ʐ]).[2]: 282

- Sometimes (especially in the beginning of a stressed syllable) it can be realized as a postalveolar affricate [d̠͡z̠], or a stop-appproximant sequence [d̠ɹ̠].[2]: 283

- It can also be realized as a postalveolar flap [ɾ̠].[2]: 282

Morphology

[edit]Panoan languages are primarily suffixing and could be called highly synthetic due to the potentially very long words (up to about 10 morphemes), but the typical number of morphemes per word in natural speech is not large. It is the large number of morphological possibilities that is striking about Panoan languages, not the typical length of words. For example, up to about 130 different verbal suffixes express such diverse notions as causation, associated motion, direction, evidentiality, emphasis, uncertainty, aspect, tense, plurality, repetition, incompletion, etc., which in languages like English would be coded by syntax or adverb words.

Ethnolinguistic Features

[edit]Linguistic Taboos:

The Shipibos and Marubos have a type of name taboo that is common in Amazonia, where birth-given names are relatively secret and cannot be used to address people or uttered loudly when talking about a living or dead person, particularly adults; instead, relational kinship terms, teknonyms, and nicknames are commonly used. [4]

Parents-in-law and their sons-in-law cannot speak directly to each other, but communicate through their daughter or wife. [4]

Gender Specific Speech:

Gender-specific language is not prominent in Panoan languages. It has only been found in interjections. Kashinawa of the Ibuaçu River and Shipibo-Konibo have two words for “yes” one used by men and the other by women

Mariage and Language:

The last one hundred years of European colonization has brought about a “leveling of dialect differences within the languages of this area. How-ever, there are still tribes and segments of tribes in relative isolation who are not as much “village” endogamous as they are “dialect” endogamous. While observing their tribal marriage rules, local people tend to marry among those who speak their own dialect. Only when the community comes into permanent contact with, or is integrated into, the national society, do dialect boundaries cease to be barriers to gene flow. [6]

References

[edit]- ^ Shipibo-Conibo at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

Tapiche Capanahua at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Valenzuela, Pinedo, & Maddieson, Pilar, Luis, Ian (15 February 2002). "Shipibo. Journal of the International Phonetic Association". Cambridge University Press: 31(2), 281-285. doi:10.1017/S0025100301002109.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Goulder, Paul (2 April 2003). "The Languages of Peru: their past, present and future survival" (PDF). Brunel.ac.uk. Brunel. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Fleck, David W. (October 10, 2013). "Panoan Languages and Linguistics". American Museum of Natural History (99). doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.5531/sp.anth.0099. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

{{cite journal}}: Check|doi=value (help); External link in|doi= - ^ Chocano, D., Baquerizo, A., Weber, R., & Colaianni, S. (2016). "CHAPTER 2: CONTINUITY AND CHANGE AMONG THE SHIPIBO-CONIBO: PREHISTORY TO MODERNITY". Fieldiana. Anthropology. 45 (New Series): 9–20. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Harriet E. Manelis Klein and Louisa R. Stark, eds (March 1987). "South American Indian Languages: Retrospect and Prospect". American Anthropologist. Volume 89. doi:https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1987.89.1.02a00520 Check |doi= value (help) – via AnthroSource

Bibliography

[edit]- Valenzuela, Pinedo, & Maddieson, Pilar, Luis, Ian (15 February 2002). "Shipibo". Journal of the International Phonetic Association: 31(2), 281-285. doi:10.1017/S0025100301002109. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Lauriault, Boonstra, Eakin, Lucille, Erwin, Harry (1986). People of the Ucayali, the Shipibo and Conibo of Peru (Volume 12-13 ed.). International Museum of Cultures. pp. 1–13. ISBN 9780883121634. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Chocano, D., Baquerizo, A., Weber, R., & Colaianni, S. (2016). "CHAPTER 2: CONTINUITY AND CHANGE AMONG THE SHIPIBO-CONIBO: PREHISTORY TO MODERNITY". Fieldiana. Anthropology. 45 (New Series): 9–20. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)</ref>

- Goulder, Paul (2 April 2003). "The Languages of Peru: their past, present and future survival" (PDF). Brunel.ac.uk. Brunel. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- Liliana Sánchez, Elisabeth Mayer, José Camacho, Carolina Rodriguez Alzza (April 2, 2018). "Linguistic attitudes toward Shipibo in Cantagallo: Reshaping indigenous language and identity in an urban setting". International Journal of Bilingualism. Vol 22 (Issue 4): 466-487. doi:10.1177/1367006918762164. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help);|volume=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Fleck, David W. (October 10, 2013). "Panoan Languages and Linguistics". American Museum of Natural History (99). doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.5531/sp.anth.0099. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

{{cite journal}}: Check|doi=value (help); External link in|doi=

- Harriet E. Manelis Klein and Louisa R. Stark, eds (March 1987). "South American Indian Languages: Retrospect and Prospect". American Anthropologist. Volume 89. doi:https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1987.89.1.02a00520 – via AnthroSource.

{{cite journal}}:|last=has generic name (help);|volume=has extra text (help); Check|doi=value (help); External link in|doi=