Sonargaon

সোনারগাঁও | |

|

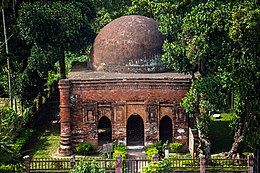

From top:Goaldi Mosque, Shilpacharya Zainul Folk Arts & Crafts Museum, Panam Nagar, Panam Nagar Architecture, Neel Kuthi | |

| Location | Narayanganj District, Dhaka Division, Bangladesh |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 23°38′51″N 90°35′52″E / 23.64750°N 90.59778°E |

| History | |

| Founded | Antiquity |

| Abandoned | 19th century |

Sonargaon (Bengali: সোনারগাঁও; Bengali pronunciation: [ˈʃonaɾɡãʋ];[1] lit. Golden Hamlet) is a historic city in central Bangladesh. It corresponds to the Sonargaon Upazila of Narayanganj District in Dhaka Division.

Sonargaon is one of the old capitals of the historic region of Bengal and was an administrative center of eastern Bengal. It was also a river port. Its hinterland was the center of the muslin trade in Bengal, with a large population of weavers and artisans. According to ancient Greek and Roman accounts, an emporium was located in this hinterland, which archaeologists have now identified with the Wari-Bateshwar ruins of the Gangaridai Empire. The area was a base for the Vanga, Gangaridai, Samatata, Sena, and Deva dynasties.

Sonargaon gained importance during the Delhi Sultanate. It was the capital of the sultanate ruled by Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah and his son Ikhtiyaruddin Ghazi Shah. It hosted a royal court and mint of the Bengal Sultanate and was also the capital of the Bengal Sultanate under the reign of Ghiyasuddin Azam Shah. Sonargaon became one of the most important townships in Bengal and many immigrants settled in the area. The Sultans built mosques and tombs. It was later the seat of the Baro-Bhuyan confederacy that resisted Mughal expansion under the leadership of Isa Khan and his son Musa Khan. Sonargaon then became a district of Mughal Bengal. During British colonial rule, merchants built many Indo-Saracenic townhouses in the Panam neighborhood. Its importance was eventually eclipsed by the nearby Port of Narayanganj which was set up in 1862.

Sonargaon draws many tourists each year in Bangladesh. It hosts the Bangladesh Folk Arts and Crafts Foundation, as well as various archaeological sites, Sufi shrines, Hindu temples, historic mosques and tombs.

History

[edit]Antiquity

[edit]

Sonargaon is located near the old course of the Brahmaputra River. To the north of Sonargaon are the Wari-Bateshwar ruins, which archaeologists have considered to be the emporium (trading colony) of Sounagoura mentioned by Greco-Roman writers.[2] The name Sonargaon originated with the ancient term of Suvarnagrama.[3] Sonargaon was ruled by Vanga and Samatata Kingdoms during antiquity. The Sena dynasty used the area as a base after they lost control of the western parts of Bengal to Bakhtiar Khalji. The Deva dynasty King Dasharathadeva shifted his capital from Bikrampur to Suvarnagrama in the middle of the 13th century.[3] Sonargaon is also one of the possible locations for the fabled land of Suvarnabhumi that is referred in cultures across the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia.

Delhi Sultanate (13th and 14th centuries)

[edit]Muslim settlers first arrived in Sonargaon circa 1281.[4] In the early 14th century, Sonargaon became part of the Delhi Sultanate when Shamsuddin Firoz Shah, Delhi's governor in Gauda, conquered central Bengal.[5] Firoz Shah built a mint in Sonargaon from where a large number of coins were issued.[5] Delhi's governors in Bengal often tried to assert their independence. Rebel governors often chose Sonargaon as the capital of Bengal. When Firoz Shah died in 1322, his son, Ghiyasuddin Bahadur Shah, replaced him as the ruler. In 1324, the Delhi Sultan Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq declared war against him and succeeded in capturing Bahadur Shah in battle. During the same year, Sultan Muhammad bin Tughlaq released him and appointed him as the governor of Sonargaon.[6]

Sonargaon began to develop as a seat of Muslim learning and Persian literature. Many Persian and Persianate Turkic immigrants settled in Sonargaon. Maulana Sharfuddin Abu Tawwama of Bukhara came to Sonargaon circa 1270 and established a Sufi khanqah and madrasa, which imparted both religious and secular education. The institutions became reputed throughout the Indian subcontinent. Sharfuddin Yahya Maneri, a celebrated Sufi scholar of Bihar, was an alumnus of Sonargaon. Tawwama's book on mysticism, Maqamat, enjoyed a strong reputation. During the administration of Roknuddin Kaikaus (1291-1301 AD), son of Nasiruddin Bughra Khan, Nam-i-Haq, a book on fiqh (jurisprudence), was written in elegant Persian poetry, in Sonargaon.[7] It is in 10 volumes and contains 180 poems. Though the authorship of this book has been ascribed to Shaikh Sharafu’d-Din Abu Tawwama, the author’s introduction testifies that the book was actually written by one of the disciples of Shaikh Sharafu’d-Din on the basis of his teachings.[7][8] The Fatwa-i-Tatarkhani was compiled at the initiative Tatar Khan, the Tughluq governor of Sonargaon.[7]

Sonargaon Sultanate (14th century)

[edit]

The Sultanate of Sonargaon became a short-lived independent state with control over central, northeastern and southeastern Bengal. When Bahram Khan died in 1338, his armour-bearer, Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah, declared himself the independent Sultan of Sonargaon.[4] Fakhruddin sponsored several construction projects, including a trunk road and raised embankments, along with mosques and tombs.[10] Sonargaon began to conquer areas held by the eastern kingdoms of Arakan and Tripura. The army of Sonargaon conquered Chittagong in southeastern Bengal in 1340. In the west, Sonargaon competed with the neighboring city-states of Lakhnauti and Satgaon for military supremacy in Bengal. Sonargaon prevailed in naval campaigns during the monsoon. Lakhnauti prevailed in land campaigns during the dry season.[11] The fourteenth-century Moorish traveler Ibn Battuta visited the Sonargaon Sultanate. He arrived through the port of Chittagong, from where he proceeded to the Sylhet region to meet with Shah Jalal. He then proceeded to Sonargaon, the capital of the sultanate. He described Fakhruddin as "a distinguished sovereign who loved strangers, particularly the fakirs and sufis". In Sonargaon's river port, Ibn Battuta boarded a Chinese junk which took him to Java.[12][10] After the death of Fakhruddin in 1349, his son Ikhtiyaruddin Ghazi Shah became the next independent ruler of Sonargaon.[13] The ruler of Satgaon Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah eventually defeated Sonargaon in 1352 and established the Bengal Sultanate.[14]

Bengal Sultanate (14th, 15th and 16th centuries)

[edit]

The three city-states of Bengal were unified into an independent sultanate. There was a decisive break from the authority of Delhi. Sonargaon became one of the major townships in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent. It was a strategically important river port with proximity to the Brahmaputra Valley and the Bay of Bengal. The third Bengali Sultan Ghiyasuddin Azam Shah established a royal court in Sonargaon. The township flourished as a center for writers, jurists and lawyers. The vast amount of Persian prose and poetry produced in Sonargaon during this period has been described as the "golden age of Persian literature" in Bengal.[8] The Sultan invited the Persian poet Hafez to the Bengali court in Sonargaon. The institutions founded by Abu Tawwama were maintained by his successors, including the Sufi preachers Saiyid Ibrahim Danishmand, Saiyid Arif Billah Muhammad Kamel, Saiyid Muhammad Yusuf and others.[7]

During the 15th century, the Chinese Treasure voyages included an expedition to Sonargaon. The Chinese embassies to Bengal were part of the mission of Admiral Zheng He. The information about this expedition comes from the book of one of its participants, Ma Huan.[1] In 1451, Ma Huan described Sonargaon as a fortified walled city,[7] with a royal court, bazaars, bustling streets, water reservoirs, and a port.

During the Hussain Shahi dynasty, Sonargaon was used as a base by the Sultans during campaigns against Assam, Tripura and Arakan. The Sultans launched raids into Assam and Tripura from Sonargaon.[15] The river port was vital during naval campaigns, such as during the Bengal Sultanate-Kamata Kingdom War and the Bengal Sultanate–Kingdom of Mrauk U War of 1512–1516.

Sonargaon hosted a mint. It was one of the most important townships in the Bengal Sultanate. It was the principal administrative center of eastern Bengal, particularly the Bhati region. High officials of the Bengal Sultanate were based in Sonargaon.[15] Turkic, Arab, Habesha, Persian settlers migrated to the region and became Sonargaiyas. Sonargaon also became the eastern terminus of the Grand Trunk Road, which was built by Sher Shah Suri in the 16th-century.[4] The Grand Trunk Road was a major trade route stretching from Bengal to Central Asia. The prosperity of the Bengal Sultanate was attested by European travelers, including Ludovico di Varthema, Duarte Barbosa and Tomé Pires. According to travelers, Sonargaon was an important commercial center. Many of its weavers and artisans were Hindus. When the Bengal Sultanate disintegrated in the late 16th-century, Sonargaon continued to be a bastion of Bengali independence for a few decades.

Baro Bhuiyans (late 16th and early 17th centuries)

[edit]

Under Sultan Taj Khan Karrani, the nobleman Isa Khan, who was prime minister in the Sultan's court, gained an estate covering the area of Sonargaon. The Karrani dynasty was defeated by Mughal forces in western Bengal. Isa Khan and a confederation of zamindars resisted Mughal expansion in eastern Bengal. The confederation is known as the Baro-Bhuyan (Twelve Bhuiyans). The confederation included Bengali Muslim and Bengali Hindu zamindars, many of whom had Turkic and Rajput ancestry who eventually became Sonargaiya through time. Isa Khan gradually increased his strength and he was designated as the ruler of the whole Bhati region, with the title of Mansad-e-Ala.

In the Ain-i-Akbari, Abul Fazl wrote about the "fine Bengali war boats" of Isa Khan's navy.[16] In the Akbarnama, Abul Fazl stated "Isa acquired fame by his ripe judgment and deliberateness, and made the twelve zamindars of Bengal subject to himself".[17] Isa Khan used the Jangalbari Fort. In 1578, the Twelve Bhuiyans defeated the Mughal viceroy Khan Jahan I under the leadership of zamindars Majlis Pratap and Majlis Dilawar, after Isa Khan was forced to retreat during a battle on the Meghna River.[18] In 1584, following an invasion by Shahbaz Khan Kamboh, Isa Khan and Masum Khan Kabuli launched a successful land and naval counterattack in Egarosindur on the banks of the Brahmaputra River, which repulsed the Mughal invasion.[19] In 1597, Isa Khan's navy dealt a massive defeat to the Mughal Navy on the Padma River. The Mughals were led by viceroy Man Singh I, who lost his son in the battle. Isa Khan's navy had surrounded the Mughal fleet on four sides.[20]

In 1580, the English traveler Ralph Fitch described Isa Khan's kingdom, stating "for here are so many Rivers and Lands, that they (Mughals) flee from one to another, whereby his (Akbar) horsemen cannot prevail against them. Great store of cotton cloth is made here. Sinnergan (Sonargaon) is a towne sixe leagues from Serrepore, where there is the best and finest cloth made of cotton that is in all India. The chief king of all these countries is called Isacan (Isa Khan), and he is chief of all the other kings, and is a great friend to all Christians".[21] In 1600, the Jesuit Mission stated that after the defeat of the Bengal Sultanate, "Twelve princes, however, called Boyones [bhūyān] who governed twelve provinces in the late King’s name, escaped from this massacre. These united against the Mongols [sic], and hitherto, thanks to their alliance, each maintains himself in his dominions. Very rich and disposing of strong forces, they bear themselves as Kings, chiefly he of Siripur [Sripur], also called Cadaray [Kedar Rai], and he of Chandecan [Raja Pratapaditya of Jessore], but most of all the Mansondolin [“Masnad-i ‘ālī,” title of Isa Khan]. The Patanes [Afghans], being scattered above, are subject to the Boyones."[22]

Isa Khan died in September 1599. His son, Musa Khan, then took control of the Bhati region. The dictionary Shabda-Ratnakari was compiled by the court poet Nathuresh during the reign of Musa Khan.[7] After the defeat of Musa Khan on 10 July 1610[23] to Mughal general Islam Khan, Sonargaon became one of the districts of Bengal Subah. The capital of Bengal later developed in the new Mughal metropolis in Dhaka.

Mughal rule (17th and 18th centuries)

[edit]Sonargaon was one of the districts (sarkars) of Mughal Bengal. The Mughals built several riverside fortifications near Sonargaon, as part of defences for the provincial capital Dhaka against Arakanese and Portuguese pirates. These include the Hajiganj Fort and Sonakanda Fort. The Mughals also built several bridges, including the Panam Bridge, Dalalpur Bridge and Panamnagar Bridge. The bridges are still in use.

- Mughal structures in and around Sonargaon

-

A 17th-century Mughal bridge over a decaying canal

British rule (18th, 19th and early 20th centuries)

[edit]During British rule in the 19th century, the neighborhood of Panam Nagar developed with townhouses, offices, temples, and mosques. European architecture influenced the design of the neighborhood. Panam was a wealthy textile business center, particularly for cotton fabrics. The merchants included Bengali Hindus, Marwaris and Bengali Muslims.[3]

Modern era

[edit]The Bangladesh Folk Arts and Crafts Foundation was established in Sonargaon by Bangladeshi painter Zainul Abedin on 12 March 1975.[4] The house, originally called Bara Sardar Bari, was built in 1901. On 15 February 1984, Narayanganj subdivision was upgraded to a district by the Government of Bangladesh.[24]

A sub-district of Narayanganj District, formerly named Baidyabazar was renamed as Sonargaon. Due to the many threats to preservation (including flooding and vandalism), Sonargaon was placed in 2008 Watch List of the 100 Most Endangered Sites by the World Monuments Fund.[25] The present-day Sonargaon is a municipality in Narayanganj District.

Trade

[edit]Sonargaon was an ancient center of muslin production and textile manufacturing. Sonargaon was famous for a cotton based cloth called Khasa for its finest quality.[26] The fertile farmland around the town also generated rice exports. The English traveler Ralph Fitch described the cotton textile weaving culture of the area in the 16th-century. Weavers formed a large part of the population. In 1580, he states "The houses here, as they be in the most part of India, are very little, and covered with straw, hay and a few mats round about the walls, and the door to keep out the Tygers and the Foxes. Many of the people are very rich. Here they will eat no flesh, nor kill no beast; They Hue of Rice, milke, and fruits, they go with a little cloth before them, and all the rest of their bodies is naked. Great store of cotton cloth goeth from hence, and much rice, wherewith they serue all India, Ceylon, Pegu, Malacca".[27] Sonargaon was a river port with access to the Bay of Bengal through the mouth of the Bengali delta.[3] Maritime ships travelled between Sonargaon and southeast/west Asian countries.[3]

- Crafts and art of Sonargaon

Demographics

[edit]At the time of the 2011 census, Sonargaon Municipality had 7,289 households a population of 32,796. 6,952 (21.20%) were under 10 years of age. Sonargaon had a literacy rate of 62.57% and a sex ratio of 951 females per 1000 males.[29]

Nearly 400 years old, it features a blend of ancient Bengali, Mughal, and colonial architecture. The main attraction is Panam Nagar, with about 52 old brick mansions.

Sonargaon Folk Art and Craft Museum: Established in 1975, this museum preserves and displays traditional Bangladeshi folk art and crafts. Visitors can explore a rich collection of textiles, pottery, woodwork, and metal crafts.

Bara Sardar Bari: Built in 1901 by Zamindar Ishan Chandra Saha, Bara Sardar Bari is a palace showcasing Mughal architecture. It now serves as part of the Sonargaon Folk Art and Craft Museum, offering insights into the zamindari history of the region.

Goaldi Mosque: This 15th-century mosque is an exquisite example of Mughal architecture, known for its intricate carvings and historical significance.

Bangladesh’s Taj Mahal: Built in 2003 by Ahsanullah Moni as a tribute to his wife, this monument is a smaller but beautiful replica of the Taj Mahal in Agra.

Joynul Abedin Smriti Jadughar: A memorial dedicated to the artist Joynul Abedin, featuring his paintings, sketches, writings, and personal belongings.

Kadam Rasul Dargah: A significant religious site believed to house the footprint of the Islamic Prophet, Muhammad known for its architectural beauty.

Panch Pirer Mazar: A popular religious site in Bhagalpur village, attracting thousands of visitors annually for prayers and pilgrimage.

Baradi: A village known for its historical significance, including Esha Khan’s palace, Sonali Mosque, and Loknath Brahmachari’s ashram.[30]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Duarte Barbosa; Mansel Longworth Dames (1996) [1918–1921]. The book of Duarte Barbosa : An Account of the Countries Bordering on the Indian Ocean and Their Inhabitants. Asian Educational Services. pp. 138–139. ISBN 81-206-0451-2.

- ^ "A Family's Passion". Archaeology Magazine.

- ^ a b c d e Muazzam Hussain Khan, Sonargaon Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Banglapedia: The National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Dhaka, Retrieved: 21 January 2012

- ^ a b c d Gope, Rabindra (2011). A visitor's guide to the Sonargaon Museum. p. 3. ISBN 978-984-33-2004-9.

- ^ a b ABM Shamsuddin Ahmed, Shamsuddin Firuz Shah Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Banglapedia: The National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Dhaka, Retrieved: 21 January 2012

- ^ Khan, Muazzam Hussain. "Ghiyasuddin Bahadur Shah". Banglapedia. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f "Sonargaon". Banglapedia.

- ^ a b "Persian". Banglapedia.

- ^ Dreyer, Edward L. (2006), Zheng He: China and the oceans in the early Ming dynasty, 1405–1433, The library of world biography, Pearson Longman, ISBN 0-321-08443-8

- ^ a b Muazzam Hussain Khan, Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah Archived 2 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Banglapedia: The National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Dhaka, Retrieved: 23 April 2011

- ^ "Alauddin Ali Shah". Banglapedia.

- ^ "Ibn Battuta". Banglapedia.

- ^ Muazzam Hussain Khan, Ikhtiyaruddin Ghazi Shah Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Banglapedia: The National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Dhaka, Retrieved: 21 January 2012

- ^ ABM Shamsuddin Ahmed, Iliyas Shah Archived 4 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Banglapedia: The National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Dhaka, Retrieved: 21 January 2012

- ^ a b "Goaldi Mosque in Sonargaon". Dhaka Tribune. 22 December 2019.

- ^ Nidhi Dugar Kundalia (24 December 2015). The Lost Generation: Chronicling India's Dying Professions. Random House India. p. 93. ISBN 978-81-8400-776-3.

- ^ Chisti, A.A. Sheikh Md. Asrarul Hoque (October 2013). The Bara-Bhuiyans and Their Times: A Study of the local anti-Mughal Resistance in Bengal (1576-1612 A.C.) (PDF) (PhD). University of Dhaka. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 September 2016.

- ^ "Isa Khan". Banglapedia.

- ^ Kunal Chakrabarti; Shubhra Chakrabarti (22 August 2013). Historical Dictionary of the Bengalis. Scarecrow Press. p. 257. ISBN 978-0-8108-8024-5.

- ^ Richard Maxwell Eaton (1996). The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204-1760. University of California Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-520-20507-9.

- ^ Ryley, J. Horton (John Horton) (1899). "Ralph Fitch, England's pioneer to India and Burma; his companions and contemporaries, with his remarkable narrative told in his own words". London, T.F. Unwin.

- ^ Richard Maxwell Eaton (1996). The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204-1760. University of California Press. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-520-20507-9.

- ^ Feroz, M A Hannan (2009). 400 years of Dhaka. Ittyadi. p. 12.

- ^ Md Solaiman, Narayanganj Archived 7 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Banglapedia: The National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Dhaka, Retrieved: 21 February 2012

- ^ "2008 World Monuments Watch List of 100 Most Endangered Sites" (PDF). World Monuments Fund. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2013. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- ^ S. B. Chakrabarti, Ranjit Kumar Bhattacharya (2002). Indian Artisans: Social Institutions and Cultural Values. Anthropological Survey of India, Government of India, Ministry of Culture, Youth Affairs and Sports, Department of Culture. p. 87. ISBN 9788185579566.

- ^ Ryley, J. Horton (1899). "Ralph Fitch".

- ^ "Bangladesh Population and Housing Census 2011 Zila Report – Narayanganj" (PDF). bbs.gov.bd. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics.

- ^ "Community Tables: Narayanganj district" (PDF). bbs.gov.bd. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. 2011.

- ^ "Sonargaon: Ancient Capital of Bangladesh - RBS Property". 20 June 2024. Retrieved 10 July 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Kazi Azizul Islam and Tania Sharmeen (5 July 2005). "Panam Among World's 100 Endangered Historic Sites". News from Bangladesh.

- Roy, Pinaki (9 July 2004). "Panam Nagar's Fate in Limbo". The Daily Star.

- Ali, Tawfique (26 April 2007). "Unscientific Restoration Defacing Heritage". The Daily Star.