Baháʼí Faith in Asia

| Part of a series on the |

| Baháʼí Faith |

|---|

|

The Baháʼí Faith was founded by Baháʼu'lláh, in Iran who faced a series of exiles and imprisonment that moved him to Baghdad, Istanbul, and Palestine. By the 1950s, about a century after its forming, Iran remained home to the vast majority of adherents to the Baháʼí Faith.[1] Expansive teaching efforts began in the late 19th century and gained converts in other parts of Asia. By 1968, according to official Baháʼí statistics, the majority of Baháʼís (~75%) lived outside of Iran and North America, the two most prominent centers of the religion previously.[1]

In 1956 there were only three Baháʼí National Spiritual Assemblies in Asia: Iran, Iraq, and India.[2] By 1967 the total was 15, and by 2001 there were 39 National Spiritual Assemblies in Asia.[3]

A Baháʼí House of Worship known as the Lotus Temple was completed in Delhi, India in 1986, and another was completed in 2017 in Battambang, Cambodia. The design for a House of Worship in Bihar Sharif, Bihar, India was unveiled in 2020. The Baháʼí World Centre, site of the Universal House of Justice (the governing body of the Baháʼí Faith) and other Baháʼí administrative buildings and holy places, is located in Israel.[4]

Baháʼís have faced severe persecution in Iran,[5] as well as varying degrees of persecution in Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Iraq, Yemen, Qatar, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Afghanistan.

Central Asia

[edit]Kazakhstan

[edit]The Baháʼí Faith in Kazakhstan began during the policy of oppression of religion in the former Soviet Union. Before that time, Kazakhstan, as part of the Russian Empire, would have had indirect contact with the Baháʼí Faith as far back as 1847.[6] By 1994 the National Spiritual Assembly of Kazakhstan was elected[7] Following the entrance of pioneers the community grew by 2001 to be the religion with the third-most registered religious organizations in the country, after Islam and Christianity.[8]

Turkmenistan

[edit]

The Baháʼí Faith in Turkmenistan begins before Russian advances into the region when the area was under the influence of Persia.[9] By 1887 a community of Baháʼí refugees from religious violence in Persia had made a religious center in Ashgabat.[9] Shortly afterwards – by 1894 – Russia made Turkmenistan part of the Russian Empire.[6] While the Baháʼí Faith spread across the Russian Empire[6][10] and attracted the attention of scholars and artists,[11] the Baháʼí community in Ashgabat built the first Baháʼí House of Worship, elected one of the first Baháʼí local administrative institutions and was a center of scholarship. However, during the Soviet period religious persecution made the Baháʼí community almost disappear – however Baháʼís who moved into the regions in the 1950s did identify individuals still adhering to the religion. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in late 1991, Baháʼí communities and their administrative bodies started to develop across the nations of the former Soviet Union;[12] In 1994 Turkmenistan elected its own National Spiritual Assembly[13] however laws passed in 1995 in Turkmenistan required 500 adult religious adherents in each locality for registration and no Baháʼí community in Turkmenistan could meet this requirement.[14] As of 2007 the religion had still failed to reach the minimum number of adherents to register[15] and individuals have had their homes raided for Baháʼí literature.[16]

Uzbekistan

[edit]The Baháʼí Faith in Uzbekistan began in the lifetime of Baháʼu'lláh, the founder of the religion.[17] Circa 1918 there was an estimated 1900 Baháʼís in Tashkent. By the period of the policy of oppression of religion in the former Soviet Union the communities shrank away – by 1963 in the entire USSR there were about 200 Baháʼís.[10] Little is known until the 1980s when the Baháʼí Faith started to grow across the Soviet Union again.[6] In 1991 a Baháʼí National Spiritual Assembly of the Soviet Union was elected but was quickly split among its former members.[6] In 1992, a regional National Spiritual Assembly for the whole of Central Asia was formed with its seat in Ashgabat.[18] In 1994 the National Spiritual Assembly of Uzbekistan was elected.[13][10] In 2008 eight Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assemblies or smaller groups had registered with the government[19] though more recently there were also raids[20] and expulsions.[21]

East Asia

[edit]China

[edit]The Baháʼí Faith was first introduced in China during the lifetime of its founder, Baháʼu'lláh. The first record of a Baháʼí living in China is of a Persian, Hájí Mírzá Muhammad-ʼAlí, who lived in Shanghai from 1862 to 1868. In 1928 the first Local Spiritual Assembly in China was formed in Shanghai.

As China expanded its reform efforts and increased its interactions with the worldwide community, more Baháʼís moved to China.

The Baháʼí Faith in China has still not matured to the same point as in many other countries of the world where there is an established structure to administer its affairs. As a result of the lack of formal registration and structure, it is difficult to ascertain with some degree of certainty, the number of Baháʼís in China. The number of active followers of Baháʼu'lláh's Teachings in China has spread beyond the scope of knowledge of the existing administrative structures. Certainly there are active followers of the teachings of Baháʼu'lláh in all of the major cities of China and in many regional centers and rural areas.

Good working relationships have been developed with China's State Administration for Religious Affairs (SARA).

According to Albert Cheung, many aspects of Baháʼu'lláh's teachings correspond closely to traditional Chinese religious and philosophical beliefs, such as: 1) the Great Unity (world peace); 2) unity of the human family; 3) service to others; 4) moral education; 5) extended family values; 6) the investigation of truth; 7) the Highest Reality (God); 8) the common foundation of religions; 9) harmony in Nature; 10) the purpose of tests and suffering; and 11) moderation in all things.[22]

Hong Kong

[edit]Hong Kong has a long history of Baha'i activity being the second location in China with Baha'is. Two brothers moved there in 1870 and established a long-running export business. Hong Kong did not have its first Local Spiritual Assembly until 1956 and then formed a National Spiritual Assembly in 1974. This was allowed because of Hong Kong's status at that time as similar to a sovereign nation and also due to the growth of the religion there. In 1997 sovereignty of Hong Kong was transferred to the People's Republic of China and it operates as a Special Administrative Area of China. The coordinating Spiritual Assembly there is no longer considered a "National" Spiritual Assembly but it still operates in a similar manner coordinating the activities of a very vibrant Baha'i community. In 2005 the Association of Religion Data Archives (relying mostly on World Christian Encyclopedia) estimated the Baháʼí population of Hong Kong at about 1,100.[23]

Macau

[edit]The Baháʼí Faith was established in Macao (also spelled Macau) much later (in 1953) than in other parts of China, most likely due to the unique conditions of Macao being a Portuguese colony until 1999 and it being somewhat in the shadow of Hong Kong and larger centers in mainland China like Shanghai. Macao formed its first Local Spiritual Assembly in 1958 and then formed a National Spiritual Assembly in 1989. In 1999 sovereignty of Macao was transferred to the People's Republic of China and it operates as a Special Administrative Area of China. The coordinating Spiritual Assembly there is no longer considered a "National" Spiritual Assembly but it still operates in a similar manner coordinating the activities of a Baháʼí community which is estimated at 2,500 and which is considered one of the five major religions of Macao.

Japan

[edit]

The Baháʼí Faith was first introduced to Japan after mentions of the country by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá first in 1875.[24] Japanese contact with the religion came from the West when Kanichi Yamamoto (山本寛一) was living in Honolulu, Hawaii in 1902 converted; the second being Saichiro Fujita (藤田左弌郎).

In 1914 two Baháʼís, George Jacob Augur and Agnes Alexander, and their families, pioneered to Japan.[25] Alexander would live some 31 years off and on in Japan until 1967 when she left for the last time[26] The first Baháʼí convert on Japanese soil was Kikutaro Fukuta (福田菊太郎) in 1915.[27] ʻAbdu'l-Bahá undertook several trips in 1911-1912 and met Japanese travelers in Western cities, in Paris,[28] London,[29] and New York.[25] ʻAbdu'l-Bahá met Fujita in Chicago and Yamamoto in San Francisco.[30]

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá wrote a series of letters, or tablets, in 1916-1917 compiled together in the book titled Tablets of the Divine Plan but which was not presented in the United States until 1919.[31] Fujita would serve between the World Wars first in the household of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá and then of Shoghi Effendi.[32] In 1932 the first Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assembly was elected in Tokyo and reelected in 1933.[33] In all of Japan there were 19 Baháʼís.[34]

In 1937 Alexander went on Baháʼí pilgrimage to return years later.[35] In 1938 Fujita was excused from his services in Haifa out of fears for his safety during World War II and returned to Japan until 1956.[36] In 1942, back in the United States, the Yamamoto family lived at a relocation camp during the war.[37] Baháʼí Americans associated with the American Occupation Forces reconnected the Japanese Baháʼí community – Michael Jamir found Fujita by 1946[37] and Robert Imagire helped re-elect the assembly in Tokyo in 1948.[37] In 1963 the statistics of Baháʼí communities showed 13 assemblies and other smaller groups.[38]

In 1968 Japanese Baháʼís began to travel outside Japan.[39] In 1971 the first residents of Okinawa converted to the religion.[40] In 1991 the community organized an affiliate of the Association for Baháʼí Studies in Japan which has since held annual conferences,[41] published newsletters, and published and coordinated academic work across affiliates.[42] The Association of Religion Data Archives (relying on World Christian Encyclopedia) estimated some 15,650 Baháʼís in 2005[23] while the CIA World Factbook estimated about 12,000 Japanese Baháʼís in 2006.[43]

Mongolia

[edit]The Baháʼí Faith in Mongolia dates back only to the 1980s and 1990s, as prior to that point Mongolia's Communist anti-religious stance impeded the spread of the religion to that country. The first Baháʼí arrived in Mongolia in 1988, and the religion established a foothold there, later establish a Local Spiritual Assembly in that nation.[44] In 1994, the Baháʼís elected their first National Spiritual Assembly.[45] Though the Association of Religion Data Archives estimated only some 50 Baháʼís in 2005[23] more than 1700 Mongolian Baháʼís turned out for a regional conference in 2009.[46] In July 1989 Sean Hinton became the first Baháʼí to reside in Mongolia, was named a Knight of Baháʼu'lláh, and the last name to be entered on the Roll of Honor at the Shrine of Baháʼu'lláh.[47]

North Korea

[edit]Baháʼís originally entered the Korean Peninsula in 1921 before the Division of Korea.[48] Both 2005 data from the Association of Religion Data Archives[23] (relying on the World Christian Encyclopedia for adherents estimates[49]) and independent research[50] agree there are no Baháʼís in North Korea.

South Korea

[edit]According to a member of the South Korean Baháʼí community, there are approximately 200 active Baháʼís in South Korea.[51]

Taiwan

[edit]The Baháʼí Faith in Taiwan began after the religion entered areas of China[52] and nearby Japan.[53] The first Baháʼís arrived in Taiwan in 1949[54] and the first of these to have become a Baháʼí was Mr. Jerome Chu (Chu Yao-lung) in 1945 while visiting the United States. By May 1955 there were eighteen Baháʼís in six localities across Taiwan. The first Local Spiritual Assembly in Taiwan was elected in Tainan in 1956. The National Spiritual Assembly was first elected in 1967 when there were local assemblies in Taipei, Tainan, Hualien, and Pingtung. Circa 2006 the Baháʼís showed up in the national census with 16,000 members and 13 assemblies.[55]

Middle East

[edit]Bahrain

[edit]The Baháʼí Faith in Bahrain begins with a precursor movement, the Shaykhís coming out of Bahrain into Iran.[56] Abu'l-Qásim Faizi and wife lived in Bahrain in the 1940s.[57] Around 1963 the first Local Spiritual Assembly of Bahrain was elected in the capital of Manama.[58] In the 1980s, many anti-Baháʼí polemics were published in local newspapers of the Bahrain.[59] Recent estimates count some 1,000 Baháʼís or 0.2% of the national population[60] or a little more by Association of Religion Data Archives estimated there were some 2,832 Baháʼís in 2010.[61] According to the Bahraini government the combined percentage of Christians, Jews, Hindus and Baháʼís is 0.2%.[62]

Iran

[edit]Estimates for number of Baháʼís in Iran in the early 21st century vary between 150,000 and 500,000. During the Iranian Revolution of 1979 and the subsequent few years, a significant number of Baháʼís left the country during intense persecution of Baháʼís. Estimates before and after the revolution vary greatly.

- Eliz Sanasarian writes in Religious Minorities in Iran[63] that "Estimating the number of Baháʼís in Iran has always been difficult due to their persecution and strict adherence to secrecy. The reported number of Baháʼís in Iran has ranged anywhere from the outrageously high figure of 500,000 to the low number of 150,000. The number 300,000 has been mentioned most frequently, especially for the mid- to late- 1970s, but it is not reliable. Roger Cooper gives an estimate of between 150,000 and 300,000."

- The Encyclopedia of the Modern Middle East and North Africa (2004) states that "In Iran, by 1978, the Baháʼí community numbered around 300,000."[64]

- The Columbia Encyclopedia (5th edition, 1993) reports that "Prior to the Iranian Revolution there were about 1 million Iranian Baháʼís."[citation needed]

- The Encyclopedia of Islam (new edition, 1960) reports that "In Persia, where different estimates of their number vary from more than a million down to about 500,000. [in 1958]"[citation needed]

Iraq

[edit]A 1970 law prohibits the Baháʼí Faith in Iraq.[65] A 1975 regulation forbade the issuance of national identity cards to Baháʼís until it was rescinded in 2007, but after only a few identity cards were issued to Baháʼís, their issuance was again halted.[65] According to Bahá’í leaders in Iraq, their community numbers less than 2,000 in that country.[65] The Bahá’í World News Service reported in May 2020 that Bahá’ís in Iraqi Kurdistan were hosting weekly online meetings on how spiritual teachings could shape public life.[66]

Israel

[edit]

The administrative centre of the Baháʼí Faith and the Shrine of the Báb are located at the Baháʼí World Centre in Haifa, and the leader of the religion is buried in Acre. Apart from maintenance staff, there is no Baháʼí community in Israel, although it is a destination for pilgrimages. Baháʼí staff in Israel do not teach their faith to Israelis following strict Baháʼí policy.[67][68]

Lebanon

[edit]The Baháʼí Faith has a following of at least several hundred people in Lebanon dating back to 1870.[69] The community includes around 400 people,[70] with a centre in Beit Mery, just outside the capital Beirut, and cemeteries in Machgara and Khaldeh. On the other hand, the Association of Religion Data Archives (relying on World Christian Encyclopedia) estimated some 3,900 Baháʼís in 2005.[23]

Qatar

[edit]On 31 March 2021, Qatari authorities blacklisted and deported a prominent Qatar-born Baháʼí, Omid Seioshansian, on "unspecified criminal and national security charges." Over the years many Baháʼís have been blacklisted and deported from Qatar. Once blacklisted, Baháʼís are expelled from the country and are permanently refused reentry. Residency permits of non-Qatari Baháʼís have also been denied, or not renewed.[71][72]

United Arab Emirates

[edit]The Baháʼí Faith in the United Arab Emirates begins before the specific country gained independence in 1971. The first Baháʼís arrived in Dubai by 1950,[73] and by 1957, there were four Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assemblies in the region of the UAE and a regional National Spiritual Assembly of the Arabian Peninsula.[7] Recent estimates count some 38,364 Baháʼís or 0.5% of the national population.[61]

Yemen

[edit]In 2018, the Houthi movement in Yemen filed charges against 20 Baháʼís in the country. Six who were held in detention were released in 2020.[74]

South Asia

[edit]Afghanistan

[edit]The history of the Baháʼí Faith in Afghanistan began in the 1880s with visits by Baháʼís. However, it was not until the 1930s that any Baháʼí settled there.[75] A Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assembly was elected in 1948 in Kabul[76] and after some years was re-elected in 1969.[77] Though the population had perhaps reached thousands, under the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the harsh rule of the Taliban the Baháʼís lost the right to have any institutions and many fled. According to a 2007 estimate, the Baháʼís in Afghanistan number approximately 400,[78] whereas the Association of Religion Data Archives gave a higher estimate of 15,000 Baháʼís in 2005.[23]

Bangladesh

[edit]The history of the Baháʼí Faith in Bangladesh began previous to its independence when it was part of India. The roots of the Baháʼí Faith in the region go back to the first days of the Bábí religion in 1844.[79] During Baháʼu'lláh's lifetime, as founder of the religion, he encouraged some of his followers to move to India.[18] And it may have been Jamál Effendi who was first sent and stopped in Dhaka more than once.[80] The first Baháʼís in the area that would later become Bangladesh was when a Bengali group from Chittagong accepted the religion while in Burma.[81] By 1950 there were enough members of the religion to elect Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assemblies in Chittagong and Dhaka.[38] The community has contributed to the progress of the nation[clarification needed] of Bangladesh individually and collectively[citation needed] and in 2005 the World Christian Encyclopedia estimated the Baháʼí population of Bangladesh about 10,600.[23]

India

[edit]

The roots of the Baháʼí Faith in India go back to the first days of the religion in 1844. A researcher, William Garlington, characterized the 1960s until present as a time of "Mass Teaching".[82] He suggests that the mentality of the believers in India changed during the later years of Shoghi Effendi's ministry, when they were instructed to accept converts who were illiterate and uneducated. The change brought teaching efforts into the rural areas of India, where the teachings of the unity of humanity attracted many people from lower castes.[citation needed] According to the 2005 Association of Religion Data Archives data there are close to some 1,880,000 Baháʼís;[23] however, the 2011 Census of India recorded only 4,572.[83][84] The Baháʼí community of India claims a Baháʼí population of over 2 million, the highest official Baháʼí population of any country.[85]

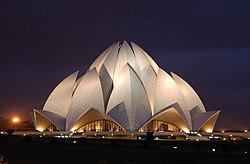

The Bahá'í House of Worship in Bahapur, New Delhi, India[86] was designed by Iranian-American architect Fariborz Sahba and is commonly known as the Lotus Temple.[87] Rúhíyyih Khánum laid the foundation stone on 17 October 1977 and dedicated the temple on 24 December 1986.[88] The total cost was $10 million.[89][90] The temple has won numerous architectural awards[91][92] and has been featured in magazines and newspapers.[93] It has also become a major attraction for people of various religions, with up to 100,000 visitors on some Hindu holy days;[92] estimates for the number of visitors annually range from 2.5 million to 5 million.[92][86][94] A 2001 a CNN reporter referred to it as the most visited building in the world.[95]

Inspired by the sacred lotus flower, the temple's design is composed of 27 free-standing, marble-clad "petals" grouped into clusters of three and thus forming nine sides.[86] The temple's shape has symbolic and inter-religious significance because the lotus is often associated with the Hindu goddess Lakshmi.[92] Nine doors open on to a central hall[91] with permanent seating for 1,200 people, which can be expanded for a total seating capacity of 2,500 people.[96] The temple rises to a height of 40.8 m[96] and is situated on a 26-acre (105,000 m2; 10.5 ha) property featuring nine surrounding ponds.[91] An educational centre beside the temple was established in 2017.[94]

A design for another House of Worship, in Bihar Sharif, Bihar, India, was unveiled in 2020.[97]

Nepal

[edit]The Baháʼí Faith in Nepal begins after a Nepalese leader encountered the religion in his travels before World War II.[98] Following World War II, the first known Baháʼí to enter Nepal was about 1952[38][99] and the first Nepalese Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assembly elected in 1961, and its National Spiritual Assembly in 1972.[100] For a period of time, between 1976 and 1981, all assemblies were dissolved due to legal restrictions.[101] The 2001 census reported 1,211 Baháʼís,[102] and since the 1990s the Baháʼí community of Nepal has been involved in a number of interfaith organizations including the Inter-religious Council of Nepal promoting peace in the country.[103]

Pakistan

[edit]The Baháʼí Faith in Pakistan begins previous to its independence when it was part of India. The roots of the Baháʼí Faith in the region go back to the first days of the Bábí religion in 1844[79] especially with Shaykh Sa'id Hindi – one of the Letters of the Living who was from Multan.[104] During Baháʼu'lláh's lifetime, as founder of the religion, he encouraged some of his followers to move to the area.[18] Jamal Effendi visited Karachi in 1875 on one of his trips to parts of Southern Asia.[104] Muhammad Raza Shirazi became a Baháʼí in Mumbai in 1908 and may have been the first Baháʼí to settle, pioneer, in Karachi.[104] National coordinated activities across India began and reached a peak by the December 1920, first All-India Baháʼí Convention, held in Mumbai for three days.[105] Representatives from India's major religious communities were present as well as Baháʼí delegates from throughout the country. In 1921, the Baháʼís of Karachi elected their first Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assembly.[104] In 1923, still as part of India, a regional National Spiritual Assembly was formed for all India and Burma which then included the area now part of Pakistan.[75] From 1931 to 1933, Professor Pritam Singh, the first Baháʼí from a Sikh background, settled in Lahore and published an English-language weekly called The Bahaʼi Weekly and other initiatives. A Baháʼí publishing committee was established in Karachi in 1935. This body evolved and is registered as the Bahaʼi Publishing Trust of Pakistan. In 1937, John Esslemont's Baháʼu'lláh and the New Era was translated into Urdu and Gujrati in Karachi.[104][106] The committee also published scores of Baháʼí books and leaflets in many languages.[107] The local assemblies spread across many cities[38] and in 1957, East and West Pakistan elected a separate national assembly from India and in 1971, East Pakistan became Bangladesh with its own national assembly.[13] Waves of refugees came from the Soviet Union invasion of Afghanistan[77] and the Islamic Revolutionin Iran[108] and later from the Taliban.[104] Some of these people were able to return home, some stayed, and others moved on. In Pakistan the Baháʼís have had the right to hold public meetings, establish academic centers, teach their faith, and elect their administrative councils.[109] However, the government prohibits Baháʼís from traveling to Israel to have Baháʼí pilgrimage.[110] Nevertheless, Baháʼís in Pakistan set up a school[104] and most of the students were not Baháʼís.[111] as well as other projects addressing the needs of Pakistan. And the religion continues to grow and in 2004 the Baháʼís of Lahore began seeking for a new Baháʼí cemetery.[112] The World Christian Encyclopedia estimated over 78,000 Baháʼís lived in Pakistan in 2000[113] though Baháʼís claimed less than half that number.[110]

Sri Lanka

[edit]A Baháʼí doctor known as Dr. Luqmani established a medical practice in Sri Lanka in 1949. In 2017, it was reported that there were about 5,000 Baháʼís in Sri Lanka.[114]

Southeast Asia

[edit]Cambodia

[edit]

The introduction of the Baháʼí Faith in Cambodia first occurred in the 1920s, not long after French Indochina was mentioned by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá as a potential destination for Baháʼí teachers.[115] After a sporadic visits from travelling teachers throughout the first half of the 20th century, the first Baháʼí group in Cambodia was established in Phnom Penh in 1956, with the arrival of Baháʼí teachers from India.[116][117] During the rule of the Khmer Rouge in the late 1970s, all effective contact with the Cambodian Baháʼís was lost.[118] The efforts of Baháʼí teachers working in Cambodian refugee camps in Thailand led to the establishment of Local Spiritual Assemblies among the survivors of the Khmer Rouge's campaign of genocide.[119] The Baháʼí community has recently seen a return to growth, especially in the city of Battambang; in 2009, the city was host to one of 41 Baháʼí regional conferences, and in 2012, the Universal House of Justice announced plans to establish a local Baháʼí House of Worship there.[120][121] According to a 2010 estimate, Cambodia is home to approximately 10,000 Baháʼís.[122]

The Battambang temple was the world's first local Baháʼí House of Worship to be completed. The temple was designed by Cambodian architect Sochet Vitou Tang, who is a practicing Buddhist, and integrates distinctive Cambodian architectural principles.[123] A dedication ceremony and official opening conference took place on 1–2 September 2017, attended by Cambodian dignitaries, locals, and representatives of Baháʼí communities throughout southeast Asia.[124][125]

Indonesia

[edit]The Baháʼí Faith's presence in Indonesia can be traced to the late 19th century, when two Baháʼís visited what is now Indonesia, as well as several other Southeast Asian countries.[126] The Mentawai Islands were one of the first areas outside the Middle East and the Western world where significant numbers of conversions to the religion took place, beginning in 1957.[1] In 2014, the Baháʼí International Community (BIC) established a regional office in Jakarta.[126] Baháʼís have been persecuted to a moderate extent in Indonesia.[127][128]

Laos

[edit]

The history of the Baháʼí Faith in Laos began after a brief mention by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in 1916[115] and the first Baháʼí entered Laos in about 1955.[129] The first Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assembly is known to be first elected by 1958 in Vientiane[38][130] and eventually Laos' own National Spiritual Assembly in 1967.[131] The current community is approximately eight thousand adherents and four centers: Vientiane, Vientiane Province, Kaysone Phomvihane, and in Pakxe.[132] and smaller populations in other provinces.[133] While well established and able to function as communities in these cities Baháʼís have a harder time in other provinces and cannot print their own religious materials.[134]

Malaysia

[edit]A large concentration of Baháʼís is also found in Malaysia, made up of Chinese, Indians, Ibans, Kadazans, Aslis and other indigenous groups. The Baháʼí community of Malaysia claims that "about 1%" of the population are Baháʼís.[135] Given the 2017 population of Malaysia, such a claim represents about 310,000 Baháʼís.

The Baháʼí Faith is one of the recognised religions in Sarawak, the largest state in Malaysia. Various races embraced the religion, from Chinese to Iban and Bidayuh, Bisayahs, Penans, Indians but not the Malays or other Muslims. In towns, the majority Baháʼí community is often Chinese, but in rural communities, they are of all races, Ibans, Bidayuhs, etc. In some schools, Baháʼí associations or clubs for students exist. Baháʼí communities are now found in all the various divisions of Sarawak. However, these communities do not accept assistance from government or other organisations for activities which are strictly for Baháʼís. If, however, these services extend to include non-Baháʼís also, e.g. education for children's classes or adult literacy, then sometimes the community does accept assistance. The administration of the religion is through local spiritual assemblies. There is no priesthood among the Baháʼís. Election is held annually without nomination or electioneering. The Baháʼís should study the community and seek those members who display mature experience, loyalty, and are knowledgeable in the religion's beliefs. There are more than 50,000 Baháʼís in more than 250 localities in Sarawak.[citation needed]

Philippines

[edit]The Baháʼí Faith in the Philippines started in 1921 with the first Baháʼí visiting the Philippines that year,[136] and by 1944 a Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assembly was established.[137] In the early 1960s, during a period of accelerated growth, the community grew from 200 in 1960 to 1,000 by 1962 and 2,000 by 1963. In 1964 the National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of the Philippines was elected and by 1980 there were 64,000 Baháʼís and 45 local assemblies.[138] The Baháʼís have been active in multi/inter-faith developments. No recent numbers are available on the size of the community.

Singapore

[edit]The Faith first came to Singapore in the 1880's, when Sulaymán Khan-i-Tunukabaní (popularly known as Jamál Effendí) and Siyyid Mustafá Roumie, stopped over in Singapore for a few weeks on their way to the Javanese and Celebes islands. Jamál Effendí was the first Persian Baháʼí sent to India by Baha'u'llah to teach the Faith in 1878. His travel companion, Mustafá Roumie was a Muslim of Iraqi descent, who became enamoured with the Baháʼí teachings and became a Baháʼí during Jamal Effendi’s teaching trip to India. Both of them decided to team up for the purpose of teaching the Faith to the inhabitants of the countries of Southeast Asia. In Singapore, they stayed in the Arab quarters, as guests of the Turkish Vice Consul, a well-known Arab merchant. They mixed freely with the Arab community. It is believed that they taught the Baháʼí Faith in Singapore to the Arab and Indian traders.

The teachings of the Faith did not take root in Singapore, until the arrival and residency of Dr. Khodadad Muncherji Fozdar and his wife, Mrs. Shirin Fozdar, in 1950. In a public lecture at the Singapore Rotary Club, then the most prestigious and male-dominated club in Singapore, Mrs. Shirin Fozdar mentioned Baháʼí principles such as universal brotherhood, unity of mankind, gender equality, universal language and peace, building a spiritual civilization and the establishment of world government.

Within two years of Dr. Fozdar’s arrival, a total of twelve declared believers in the Baháʼí Faith emerged. Mr. Naraindas Jethanand was the first declared believer of the Faith in Singapore. The first Local Spiritual Assembly was elected in April 1952. The history of Singapore and Malaysian Baháʼí communities are closely linked, as Mrs. Fozdar gave talks in Singapore and Malaya, and other Baháʼí teachers and believers would travel between the two countries to teach the Faith. There are currently five Local Spiritual Assemblies under the jurisdiction of the Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Singapore, the national governing council, which was established in April 1972.

The mid 1990s to the early part of the 21st century saw the Bahá’í community in Singapore spearheading efforts to promote interfaith engagement in multi-religious Singapore. The World Religion Day observances, initiated and organized by the Bahá’í community in Singapore, gained nationwide prominence and support, and became the precursor for many interfaith endeavours that proliferate in Singapore now. The Bahá’í Faith became one of the constituent religions of the Inter-Religious Organisation of Singapore (IRO) in 1996. The Baháʼí community continues to participate and collaborate in interfaith events, actively promoting understanding, dialogue and interaction between different religions.

To initiate a thoughtful and self-reflective exploration into the role of religion to build an ever-advancing civilisation, the Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Singapore submitted a paper titled Rethinking the Role of Religion in the midst of our changing aspirations and increasing diversity[139] in November 2012 as a contribution to Our Singapore Conversation.

Vietnam

[edit]

The introduction of the Baháʼí Faith in Vietnam first occurred in the 1920s, not long after French Indochina was mentioned by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá as a potential destination for Baháʼí teachers.[115] After a number of brief visits from travelling teachers throughout the first half of the 20th century, the first Baháʼí group in Vietnam was established in Saigon in 1954, with the arrival of Shirin Fozdar, a Baháʼí teacher from India. The 1950s and 1960s were marked by periods of rapid growth, mainly in South Vietnam; despite the war then affecting the country, the Baháʼí population surged to around 200,000 adherents by 1975. After the end of the war, Vietnam was reunified under a communist government, who proscribed the practice of the religion from 1975 to 1992, leading to a sharp drop in community numbers. Relations with the government gradually improved, however, and in 2007 the Baháʼí Faith was officially registered, followed by its full legal recognition a year later.[140][141] As of 2011, it was reported that the Baháʼí community comprised about 8,000 followers.[142]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c Momen & Smith 1989.

- ^ Hassall 2000.

- ^ Bolhuis 2001.

- ^ Smith 2000, pp. 71–72.

- ^ International Federation for Human Rights (1 August 2003). "Discrimination against religious minorities in Iran" (PDF). fdih.org. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

- ^ a b c d e Momen, Moojan. "Russia". Draft for "A Short Encyclopedia of the Baháʼí Faith". Baháʼí Academics Resource Library. Retrieved 14 April 2008.

- ^ a b The Baháʼí Faith: 1844–1963: Information Statistical and Comparative, Including the Achievements of the Ten Year International Baháʼí Teaching & Consolidation Plan 1953–1963, Compiled by Hands of the Cause Residing in the Holy Land, pages 22 and 46.

- ^ Government of Kazakhstan (2001). "Religious Groups in Kazakhstan". 2001 Census. Embassy of Kazakhstan to the USA & Canada. Archived from the original on 31 October 2006. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- ^ a b Momen, Moojan. "Turkmenistan". Draft for "A Short Encyclopedia of the Baháʼí Faith". Baháʼí Academics Resource Library. Retrieved 23 May 2008.

- ^ a b c Local Spiritual Assembly of Kyiv (2007). "Statement on the history of the Baháʼí Faith in Soviet Union". Official Website of the Baháʼís of Kyiv. Local Spiritual Assembly of Kyiv. Archived from the original on 15 July 2010. Retrieved 19 April 2008.

- ^ Smith 2000, p. 340.

- ^ Hassall, Graham; Fazel, Seena. "100 Years of the Baháʼí Faith in Europe". Baháʼí Studies Review. Vol. 1998, no. 8. pp. 35–44.

- ^ a b c Notes on Research on National Spiritual Assemblies Asia Pacific Baháʼí Studies.

- ^ compiled by Wagner, Ralph D. "Turkmenistan". Synopsis of References to the Baháʼí Faith, in the US State Department's Reports on Human Rights 1991–2000. Baháʼí Academics Resource Library. Retrieved 25 May 2008.

- ^ U.S. State Department (14 September 2007). "Turkmenistan – International Religious Freedom Report 2007". The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affairs. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- ^ Corley, Felix (1 April 2004). "TURKMENISTAN: Religious communities theoretically permitted, but attacked in practice?". F18News.

- ^ Hassall, Graham (1993). "Notes on the Babi and Baha'i Religions in Russia and its territories". Journal of Baháʼí Studies. 05 (3): 41–80, 86. doi:10.31581/JBS-5.3.3(1993). Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- ^ a b c Momen, Moojan; Smith, Peter. "Baháʼí History". Draft A Short Encyclopedia of the Baha'i Faith. Baháʼí Library Online. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- ^ "Republic of Uzbekistan". Journal Islam Today. 1429H/2008 (25). Islamic Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. 2008. Archived from the original on 2 September 2009. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- ^ Corley, Felix (24 September 2009). "They can drink tea – that's not forbidden". Forum 18. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- ^ Corley, Felix (16 February 2010). "UZBEKISTAN: Two more foreigners deported for religious activity". Forum 18. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- ^ Cheung, Albert. "Common Teachings from Chinese Culture and the Baha'i Faith: From Material Civilization to Spiritual Civilization" Published in Lights of Irfan, Book 1, pages 37–52 Wilmette, IL: Irfan Colloquia, Web Published (2000); http://bahai-library.com/?file=cheung_chinese_bahai_teachings.htm

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Most Baha'i Nations (2005)". QuickLists > Compare Nations > Religions >. The Association of Religion Data Archives. 2005. Archived from the original on 14 April 2010. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- ^ ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1990) [1875], The Secret of Divine Civilization, Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust, p. 111, ISBN 0-87743-008-X

- ^ a b Alexander 1977, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Sims 1989, pp. 9.

- ^ Alexander 1977, pp. 12–4, 21.

- ^ Lady Blomfield (1967) [1940], The Chosen Highway, Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust, p. 229, ISBN 978-0-85398-509-9

- ^ Sims 1989, pp. 24.

- ^ Sims 1989, pp. 1–2.

- ^ ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1991) [1916-17], Tablets of the Divine Plan (Paperback ed.), Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust, p. 43, ISBN 0-87743-233-3

- ^ Sims 1989.

- ^ Sims 1989, pp. 20.

- ^ Sims 1989, pp. 64.

- ^ Sims 1989, pp. 115–6.

- ^ Ioas, Sylvia (24 November 1965). "Interview of Sachiro Fujita". Pilgrim Notes. Baháʼí Academics Online. Retrieved 24 January 2008.

- ^ a b c Sims 1989, p. 115.

- ^ a b c d e Hands of the Cause. "The Baháʼí Faith: 1844–1963: Information Statistical and Comparative, Including the Achievements of the Ten Year International Baháʼí Teaching & Consolidation Plan 1953–1963". pp. 51, 107.

- ^ Sims 1989, p. 214.

- ^ Sims 1989, pp. 21–26.

- ^ "Annual Conferences". Official Webpage of the Japanese affiliate of the Association of Baháʼí Studies. Japanese affiliate of the Association of Baháʼí Studies. 2008. Archived from the original on 4 March 2009. Retrieved 26 January 2008.

- ^ Yerrinbool Report on Scholarship 1999 Affiliate Associations for Baháʼí Studies-Japan

- ^ "Japan Profile". About Asia. Overseas Missionary Fellowship International. 2006. Archived from the original on 20 November 2008. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ^ Smith 2008, p. 95.

- ^ "Mongolia". National Communities. Baháʼí International Community. 2010. Archived from the original on 9 July 2010. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- ^ "The Ulaanbaatar Regional Conference". Baháʼí International News Service. 25 January 2009.

- ^ "A Brief History of the Baháʼí Faith". Fourth Epoch of the Formative Age: 1986 – 2001. Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Boise, Idaho, U.S.A. 9 May 2009. Archived from the original on 11 September 2010. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- ^ Sims, Barbara R. (1996). "The First Mention of the Baháʼí Faith in Korea". Raising the Banner in Korea; An Early Baháʼí History. National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Korea.

- ^ "Data Sources". National Profiles. The Association of Religion Data Archives.

- ^ Smith 2008, pp. 79, 95.

- ^ Matthew Lamers (30 March 2010). "Small but vibrant: Baha'is in Korea". The Korea Herald. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ^ Hassall, Graham (January 2000). "The Baháʼí Faith in Hong Kong". Official website of the Baháʼís of Hong Kong. National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Hong Kong. Retrieved 12 November 2010.

- ^ Alexander 1977.

- ^ R. Sims, Barbara (1994). The Taiwan Baháʼí Chronicle: A Historical Record of the Early Days of the Baháʼí Faith in Taiwan. Tokyo: Baháʼí Publishing Trust of Japan.

- ^ "Taiwan Yearbook 2006". Government of Information Office. 2006. Archived from the original on 8 July 2007. Retrieved 1 September 2007.

- ^ Nabíl-i-Zarandí (1932). The Dawn-Breakers: Nabíl's Narrative. Translated by Shoghi Effendi (Hardcover ed.). Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-900125-22-5.

- ^ Universal House of Justice (1986). In Memoriam. Vol. XVIII. Baháʼí World Centre. p. 663. ISBN 978-0-85398-234-0.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ The Baháʼí Faith: 1844–1963: Information Statistical and Comparative, Including the Achievements of the Ten Year International Baháʼí Teaching & Consolidation Plan 1953-1963, Compiled by Hands of the Cause Residing in the Holy Land, pages 25, 26, 58.

- ^ MacEoin, Denis; William Collins. "Anti-Baha'i Polemics". The Babi and Baha'i Religions: An Annotated Bibliography. Greenwood Press's ongoing series of Bibliographies and Indexes in Religious Studies. pp. entries #157, 751, 821. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ Kjeilen, Tore, ed. (2008), "Baha'i", Looklex Encyclopedia, an expansion of Encyclopaedia of the Orient, vol. Online, Looklex Encyclopedia

- ^ a b "Most Baha'i Nations (2010)". The Association of Religious Data Archives. Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ^ "Population and Demographics – Ministry of Information Affairs | Kingdom of Bahrain". Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ^ Sanasarian 2000, p. 53.

- ^ Philip Mattar (2004). Encyclopedia of the Modern Middle East & North Africa: A-C. Macmillan Reference USA. p. 365. ISBN 978-0-02-865770-7.

- ^ a b c "Iraq: International Religious Freedom Report". International Religious Freedom Report. U.S. State Department. 26 October 2009. Archived from the original on 31 October 2009. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ^ "Looking beyond the health crisis in the Kurdistan region of Iraq". Bahá’í World News Service. 3 May 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- ^ "The Baháʼí World Centre: Focal Point for a Global Community". The Baháʼí International Community. Archived from the original on 29 June 2007. Retrieved 2 July 2007.

- ^ "Teaching the Faith in Israel". Baháʼí Library Online. 23 June 1995. Retrieved 6 August 2007.

- ^ The Bahaʼi faith in Lebanon, Al Nahar (newspaper), 2009-09-12

- ^ Sects And The City: The 19th Sect Of Lebanon? Archived 2012-04-08 at the Wayback Machine, Seif and his Beiruti Adventures, 21 January 2011

- ^ "Qatar expelling and blacklisting Baha'is could indicate pattern of religious cleansing". www.bic.org. 31 March 2021. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ Staff, ADHRB (8 September 2019). "UN Special Procedures Publish Allegation Letter to Qatar on Discriminatory Treatment of the Bahá'í Religious Minority". Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ The Baháʼí Faith: 1844–1963: Information Statistical and Comparative, Including the Achievements of the Ten Year International Baháʼí Teaching & Consolidation Plan 1953–1963, Compiled by Hands of the Cause Residing in the Holy Land, pages 4, 25, 28, 118.

- ^ "Yemen's Houthis release six Baha'i prisoners". Reuters. 30 July 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- ^ a b Hassall, Graham. "Notes on Research Countries". Research notes. Asia Pacific Baháʼí Studies. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- ^ Cameron, G.; Momen, W. (1996). A Basic Baháʼí Chronology. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. pp. 277, 391. ISBN 0-85398-404-2.

- ^ a b "Baháʼí Faith in Afghanistan". Archived from the original on 16 July 2007. Retrieved 25 July 2007.

- ^ U.S. State Department (14 September 2007). "Afghanistan – International Religious Freedom Report 2007". The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affairs. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- ^ a b "The Baháʼí Faith -Brief History". Official website of the National Spiritual Assembly of India. National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of India. 2003. Archived from the original on 14 April 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- ^ Momen, Moojan (2000). "Jamál Effendi and the early spread of the Baháʼí Faith in Asia". Baháʼí Studies Review. 09 (1999/2000). Association for Baha'i Studies (English-Speaking Europe). Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- ^ Ali, Meer Mobashsher (2012). "Bahai". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ^ "The Baha'i Faith in India". www.h-net.org. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "C-01 Appendix : Details of Religious Community Shown Under 'Other Religions And Persuasions' In Main Table C-1- 2011 (India & States/UTs)". Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- ^ "Population Enumeration Data (Final Population)". Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- ^ Baha'i Faith in India Archived 14 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine, FAQs, National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of India

- ^ a b c Hassall 2012.

- ^ Mackin-Solomon 2013.

- ^ Momen 2010.

- ^ Warburg 1993.

- ^ Smith 2000, p. 241.

- ^ a b c Rizor 2011.

- ^ a b c d Garlington 2006.

- ^ Baháʼí World News Service 2000.

- ^ a b Pearson 2022.

- ^ "Encore Presentation: A Visit to the Capital of India: New Delhi". Cable News Network. 14 July 2001. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ a b Rafati & Sahba 1988.

- ^ "Local Temple design unveiled in India". Bahá’í World News Service. 29 April 2020. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ Effendi, Shoghi (1938–1940). "Appreciations of the Baháʼís Faith". The Baháʼí World. VIII. Baháʼí World Centre: 63–65.

- ^ Sarwal, Anil. "Baháʼí Faith in Nepal". Baháʼí Articles. Prof. Anil Sarwal. Archived from the original on 20 September 2008. Retrieved 4 September 2008.

- ^ Marks, Geoffry W., ed. (1996). Messages from the Universal House of Justice, 1963–1986: The Third Epoch of the Formative Age. Baháʼí Publishing Trust, Wilmette, Illinois, US. ISBN 0-87743-239-2.

- ^ Universal House of Justice (1996). "To the Followers of Baháʼu'lláh in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Bangladesh, India, Nepal and Sri Lanka, Baháʼí Era 153". Ridván 1996 (Four Year Plan). Baháʼí Library Online. Retrieved 4 May 2008.

- ^ Central Bureau of Statistics (2001). "Table 17: Populations by Religion, five-year age group and sex for regions". 2001 Census. Nepal: National Planning Commission Secretariat.

- ^ U.S. State Department (14 September 2007). "Nepal – International Religious Freedom Report 2007". The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affair. Retrieved 5 September 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g "History of the Baháʼí Faith in Pakistan". Official Webpage of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Pakistan. National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Pakistan. 2008. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- ^ Garlington 1997.

- ^ Baháʼí International Community. ""Baháʼu'lláh and the New Era" editions and printings held in Baháʼí World Centre Library Decade by decade 1920 -2000+". General Collections. International Baháʼí Library. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- ^ MacEoin, Denis; William Collins. "Memorials (Listings)". The Babi and Baha'i Religions: An Annotated Bibliography. Greenwood Press's ongoing series of Bibliographies and Indexes in Religious Studies. Entry No. 45, 56, 95, 96. Retrieved 6 April 2009.

- ^ Chun, Lisa (16 July 2008). "Message of Persecution – Fairfax doctor recalls Iranian persecution of father, members of Baháʼí faith". Arlington Connection. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011.

- ^ Wardany, Youssef (2009). "The Right of Belief in Egypt: Case study of Baha'i minority". Al Waref Institute. Archived from the original on 15 March 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- ^ a b compiled by Wagner, Ralph D. "Pakistan". Synopsis of References to the Baháʼí Faith, in the US State Department's Reports on Human Rights 1991–2000. Baháʼí Academics Resource Library. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- ^ "Building a Just World Order". BIC Statements. Baháʼí International Community. 29 March 1985. Archived from the original on 4 September 2009. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- ^ Akram, Ayesha Javed (7 June 2004). "The Bahai community: Lying low: the need for a new graveyard". Daily Times (Pakistan). Archived from the original on 17 October 2012.

- ^ "Top 20 Largest National Baha'i Populations". Adherents.com. 2008. Archived from the original on 19 October 2008. Retrieved 18 November 2008.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Nazim, Aisha (6 October 2017). "Sri Lanka's Lesser Known Religious Minority: The Bahá'í". Roar Media. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ a b c ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1991) [1916-17]. Tablets of the Divine Plan (Paperback ed.). Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. pp. 40–42. ISBN 0877432333.

- ^ Messages of Shoghi Effendi to the Indian Subcontinent: 1923–1957. Baháʼí Publishing Trust of India. 1995. p. 403. ISBN 85-85091-87-8.

- ^ "Teaching and Assembly Development Conference for Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos and Thailand". Baháʼí News Letter (85). National Spiritual Assembly of the Baha'is of India, Pakistan & Burma. December 1956.

- ^ "Religious Freedom in the Asia Pacific". bahai-library.com. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ The Universal House of Justice. Century of Light. p.104. http://reference.bahai.org/en/t/bic/COL/col-11.html

- ^ "The Battambang Regional Conference - Bahá'í World News Service". news.bahai.org. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "Plans to build new Houses of Worship announced | BWNS". Bahá’í World News Service. 22 April 2012. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "Cambodia". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "Spirit and aspirations of a people: Reflections of Temple's architect". Baháʼí World News Service. 31 August 2017. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ "Preparations for Temple inauguration accelerate | Baháʼí World News Service (BWNS)". Baháʼí World News Service. 11 August 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ "Inauguration conference concludes". Bahá’í World News Service. 2 September 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Exploring religion's contribution to peace in Southeast Asia". Baháʼí World News Service. 17 November 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- ^ "Indonesia: International Religious Freedom Report". U.S. State Department. 26 October 2001. Retrieved 3 March 2007.

- ^ "Indonesia: International Religious Freedom Report". U.S. State Department. 26 October 2009. Archived from the original on 19 April 2010. Retrieved 19 April 2010.

- ^ Effendi, Shoghi (April 1956). Messages to the Baháʼí World: 1950–1957 (1971 ed.). Wilmette, USA: US Baháʼí Publishing Trust. p. 92.

- ^ "Vientiane Assembly Legally Recognized". Baháʼí News (353): 8. August 1960.

- ^ Hassall 2000

- ^ U.S. State Department (15 September 2006). "Laos – International Religious Freedom Report 2006". The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affair. Retrieved 30 December 2008.

- ^ U.S. State Department (26 October 2005). "Laos – International Religious Freedom Report 2001". The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affair. Retrieved 30 December 2008.

- ^ U.S. State Department (8 November 2005). "Laos – International Religious Freedom Report 2005". The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affair. Retrieved 30 December 2008.

- ^ "50 years of the Baháʼí Faith in Malaysia". National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Malaysia. Archived from the original on 6 July 2007.

- ^ Hassall, Graham; Austria, Orwin (January 2000). "Mirza Hossein R. Touty: First Baháʼí known to have lived in the Philippines". Essays in Biography. Asia Pacific Baháʼí Studies. Retrieved 1 June 2008.

- ^ Effendi, Shoghi (1944). God Passes By. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. ISBN 0-87743-020-9.

- ^ Universal House of Justice (1986). In Memoriam. Vol. XVIII. Baháʼí World Centre. 513, 652–9 and Table of Contents. ISBN 0-85398-234-1.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ The Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of Singapore (30 November 2012). "Rethinking the role of Religion in the midst of our changing aspirations and increasing diversity" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Small Baha'i And Muslim Communities Grow in Hanoi". Embassy of the United States of America in Vietnam. 12 September 2007. Archived from the original (Diplomatic cable) on 21 February 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ^ "International Religious Freedom Report — Vietnam". United States State Department. 14 September 2007. Retrieved 23 February 2008.

- ^ "International Religious Freedom Report—Vietnam". United States State Department. 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

References

[edit]- Alexander, Agnes Baldwin (1977). Barbara Sims (ed.). History of the Baháʼí Faith in Japan 1914-1938. Osaka, Japan: Japan Baháʼí Publishing Trust.

- "Baha'i Temple in India continues to receive awards and recognitions". Baháʼí World News Service. 5 December 2000. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- Bolhuis, Arjen (2001). "Bahá'í World Statistics 2001".

- Garlington, William (1997). "The Baha'i Faith in India". Occasional Papers in Shaykhi, Babi and Baha'i Studies. 2. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- Garlington, William (2006). "Indian Baha'i tradition". In Mittal, Sushil; Thursby, Gene R. (eds.). Religions of South Asia. London: Routledge. pp. 247–260. ISBN 0415223903.

- Hassall, Graham (2000). "National Spiritual Assemblies: Lists and years of formation". Research notes. Asia Pacific Baháʼí Studies. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- Hassall, Graham (2012). "The Bahá'í House of Worship: Localisation and Universal Form". In Cusack, Carol; Norman, Alex (eds.). Handbook of New Religions and Cultural Production. Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion. Vol. 4. Leiden: Brill. pp. 599–632. doi:10.1163/9789004226487_025. ISBN 978-90-04-22187-1. ISSN 1874-6691.

- Mackin-Solomon, Ashley (23 January 2013). "Iranian architect living in La Jolla devoted to creating 'spiritual space'". La Jolla Light. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- Momen, Moojan (2010). "Mašreq al-Aḏkār". Encyclopædia Iranica (online ed.).

- Momen, Moojan; Smith, Peter (1989). "The Baha'i Faith 1957–1988: A Survey of Contemporary Developments". Religion. 19: 63–91. doi:10.1016/0048-721X(89)90077-8.

- Pearson, Anne M. (2022). "Ch. 49: South Asia". In Stockman, Robert H. (ed.). The World of the Bahá'í Faith. Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge. pp. 603–613. doi:10.4324/9780429027772-56. ISBN 978-1-138-36772-2. S2CID 244701542.

- Rafati, V.; Sahba, F. (1988). "BAHAISM ix. Bahai temples". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. III. pp. 465–467.

- Rizor, John (21 August 2011). "AD Classics: Lotus Temple / Fariborz Sahba". ArchDaily. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- Sanasarian, Eliz (2000). Religious Minorities in Iran. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-42985-6.

- Sims, Barbara (1989). Traces That Remain: A Pictorial History of the Early Days of the Baháʼí Faith among the Japanese. Tokyo, Japan: Baháʼí Publishing Trust of Japan.

- Smith, Peter (2000). A Concise Encyclopedia of the Baháʼí Faith. Oneworld Publications, Oxford, England. ISBN 1-85168-184-1.

- Smith, Peter (2008). An Introduction to the Baha'i Faith. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86251-6.

- Warburg, Margit (1993). "Economic Rituals: The Structure and Meaning of Donations in the Baha'i Religion". Social Compass. 40 (1): 25–31. doi:10.1177/003776893040001004. S2CID 144837705.

Further reading

[edit]- Brookshaw, Dominic P.; Fazel, Seena B., eds. (2008). The Baha'is of Iran: Socio-historical studies. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-00280-3.

- Garlington, William (2006). "Indian Baha'i tradition". In Mittal, Sushil; Thursby, Gene R. (eds.). Religions of South Asia. London: Routledge. pp. 247–260. ISBN 0415223903.

- Geller, Randall S. (2019). "The Baha'i minority in the State of Israel, 1948–1957". Middle Eastern Studies. 55 (3): 403–418. doi:10.1080/00263206.2018.1520100. S2CID 149907274.

External links

[edit]- Baháʼí World Statistics

- adherents.com – Compiled statistics on Baháʼí communities