Annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation

| Annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Russo-Ukrainian War | |||||||

Russian President Vladimir Putin signs the treaty of accession (annexation) with Crimean leaders in Moscow, 18 March 2014. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

Based in Crimea, Navy

Deployed to Crimea, elements of Ground Forces

(GRU command)

Airborne

Navy

Special Operations Forces

|

Armed forces[11]: 11–12 Navy

Paramilitary Interior troops

Border guards

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Protesters

Russian military forces

|

Protesters Ukrainian military forces | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1 Crimean SDF trooper killed[23] | |||||||

| 2 civilian deaths (during the protests),[28][29] 1 civilian killed[30][31] (by Crimean SDF under command of a former Russian serviceman)[32][33] | |||||||

In February and March 2014, Russia invaded the Crimean Peninsula, part of Ukraine, and then annexed it. This took place in the relative power vacuum[34] immediately following the Revolution of Dignity. It marked the beginning of the Russo-Ukrainian War.

The events in Kyiv that ousted Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych on 22 February 2014 sparked pro-Russian and anti-separatism[35] demonstrations in Crimea. At the same time, Russian president Vladimir Putin discussed Ukrainian events with security chiefs, remarking that "we must start working on returning Crimea to Russia". On 27 February, Russian special forces without insignia[36] seized strategic sites across Crimea.[37][38] Although Russia at first denied its military involvement,[39] Putin later admitted that troops were deployed to "stand behind Crimea's self-defence forces".[40] As Russian troops occupied Crimea's parliament, it dismissed the Crimean government, installed the pro-Russian Aksyonov government, and announced a referendum on Crimea's status. The referendum was held under Russian occupation and, according to the Russian-installed authorities, the result was overwhelmingly in favor of joining Russia. The next day, 17 March 2014, Crimea's authorities declared independence and requested to join Russia.[41][42] Russia formally incorporated Crimea on 18 March 2014 as the Republic of Crimea and federal city of Sevastopol.[43][40] Following the annexation,[44] Russia built up its military presence on the peninsula and warned against any outside intervention.[45]

Ukraine and many other countries condemned the annexation and consider it to be a violation of international law and Russian agreements safeguarding the territorial integrity of Ukraine. The annexation led to the other members of the G8 suspending Russia from the group[46] and introducing sanctions. The United Nations General Assembly also rejected the referendum and annexation, adopting a resolution affirming the "territorial integrity of Ukraine within its internationally recognised borders",[47][48] and referring to the Russian action as a "temporary occupation".[49]

The Russian government opposes the "annexation" label, with Putin defending the referendum as complying with the principle of the self-determination of peoples.[50][51]

Other names

In Ukraine

The names of the Crimean annexation vary. In Ukraine, the annexation is known as the temporary occupation of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol by Russia (Ukrainian: тимчасова окупація Автономної Республіки Крим і Севастополя Росією, romanized: tymchasova okupatsiia Avtonomnoi Respubliky Krym i Sevastopolia Rosiieiu), the illegal occupation of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, the fall of Crimea, and the invasion of Crimea.[52][53][54][55]

In Russia

In the Russian Federation, it is also known as the accession of Crimea to the Russian Federation (Russian: присоединение Крыма к Российской Федерации, romanized: prisoyedineniye Kryma k Rossiyskoy Federatsii), the return of Crimea (Russian: возвращение Крыма, romanized: vozvrashcheniye Kryma), and the reunification of Crimea.[56][57]

Background

Crimea was part of the Crimean Khanate from 1441 until it was annexed by the Russian Empire in 1783 by a decree of Catherine the Great.[58][59][60]

After the downfall of Russian empire in 1917 during the first stages of the Russian Civil War there were a series of short-lived independent governments (Crimean People's Republic, Crimean Regional Government, Crimean SSR). They were followed by White Russian governments (General Command of the Armed Forces of South Russia and later South Russian Government).

In October 1921, the Bolshevik Russian SFSR gained control of the peninsula and instituted the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic as a member of Russian Federation. In the following year Crimea joined the Soviet Union as a part of Russia (the RSFSR).

After the Second World War and the 1944 deportation of all of the indigenous Crimean Tatars by the Soviet government, the Crimean ASSR was stripped of its autonomy in 1946 and downgraded to the status of an oblast of the Russian SFSR. In 1954, the Crimean Oblast was transferred from the Russian SFSR to the Ukrainian SSR by decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union to commemorate the 300th anniversary of Ukraine's union with Russia.[61][62] In 1989, under Gorbachev's perestroika,[63] the Supreme Soviet declared that the deportation of the Crimean Tatars under Stalin had been illegal[64] and the mostly Muslim ethnic group was allowed to return to Crimea.[65]

In 1990, the Soviet of the Crimean Oblast proposed the restoration of the Crimean ASSR.[66] The oblast conducted a referendum in 1991, which asked whether Crimea should be elevated into a signatory of the New Union Treaty (that is, become a union republic on its own). By that time, though, the dissolution of the Soviet Union was well underway. The Crimean ASSR was restored for less than a year as part of Ukrainian SSR before the restoration of Ukrainian independence.[67] Newly independent Ukraine maintained Crimea's autonomous status,[68] while the Supreme Council of Crimea affirmed the peninsula's "sovereignty" as a part of Ukraine.[69][70]

The confrontation between the government of Ukraine and Crimea deteriorated between 1992 and 1995. In May 1992 the regional parliament declared an independent "Crimean republic."[71] In June 1992, the parties reached a compromise, that Crimea would have considerable autonomy but remain part of Ukraine.[72] Yuri Meshkov, a leader of the Russian movement was elected President of Crimea in 1994 and his party won a majority in the regional parliamentary elections in the same year. The pro-Russian movement was then weakened by internal disagreements and in March 1995 the Ukrainian government gained the upper hand. The office of the elected President of Crimea was abolished and a loyal head of region was installed instead of Meshkov; the 1992 constitution and a number of local laws were repealed.[71] According to Gwendolyn Sasse the conflict was defused due to Crimea's multi-ethnic population, fractures within the pro-Russian movement, Kyiv's policy of avoiding escalation and the lack of active support from Russia.[71]

During the 1990s, the dispute over control of the Black Sea Fleet and Crimean naval facilities were source of tensions between Russia and Ukraine. In 1992, Vladimir Lukin, then chairman of the Russian Duma's Committee on Foreign Affairs, suggested that in order to pressure Ukraine to give up its claim to the Black Sea Fleet, Russia should question Ukrainian control over Crimea.[73] In 1998 the Partition Treaty divided the fleet and gave Russia a naval base in Sevastopol, and the Treaty of Friendship recognized the inviolability of existing borders. However, in 2003 Tuzla Island conflict issues over maritime border resurfaced.

In September 2008, the Ukrainian Foreign Minister Volodymyr Ohryzko accused Russia of giving Russian passports to the population in Crimea, and described it as a "real problem", given Russia's declared policy of military intervention abroad to protect Russian citizens.[74]

On 24 August 2009, anti-Ukrainian demonstrations were held in Crimea by ethnic Russian residents. Sergei Tsekov (of the Russian Bloc[75] and then deputy speaker of the Crimean parliament[76]) said then that he hoped that Russia would treat Crimea the same way as it had treated South Ossetia and Abkhazia.[77] Crimea is populated by an ethnic Russian majority and a minority of both ethnic Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars, and thus demographically possessed one of Ukraine's largest ethnically Russian populations.[78]

As early as in 2010, some analysts already speculated that the Russian government had irredentist plans. Taras Kuzio said that "Russia has an even more impossible time recognizing Ukraine's sovereignty over the Crimea and the port of Sevastopol – as seen by public opinion in Russia, statements by politicians, including members of the ruling United Russia party, experts and journalists".[79] In 2011, William Varettoni wrote that "Russia wants to annex Crimea and is merely waiting for the right opportunity, most likely under the pretense of defending Russian brethren abroad".[80]

Euromaidan and the Revolution of Dignity

The Euromaidan protest movement began in Kyiv in late November 2013 after President Viktor Yanukovych, of the Party of Regions, failed to sign the Ukraine–European Union Association Agreement.[81] Yanukovych won [82] the 2010 presidential election with strong support from voters in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and southern and eastern Ukraine. The Crimean autonomous government strongly supported Yanukovych and condemned the protests, saying they were "threatening political stability in the country". The Crimean autonomous parliament said that it supported the government's decision to suspend negotiations on the pending association agreement and urged Crimeans to "strengthen friendly ties with Russian regions".[83][84][85]

On 4 February 2014, the Presidium of the Supreme Council "promised" to consider holding a referendum on the peninsula's status. Speaker Vladimir Klychnikov asked to appeal to the Russian government to "guarantee the preservation of Crimean autonomy".[86][87][importance?] The Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) responded by opening a criminal case to investigate the possible "subversion" of Ukraine's territorial integrity.[88] On 20 February 2014, during a visit to Moscow, Chairman of the Supreme Council of Crimea Vladimir Konstantinov stated that the 1954 transfer of Crimea from the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic had been a mistake.[86]

The Euromaidan protests came to a head in late February 2014, and Yanukovych and many of his ministers fled the capital on 22 February.[89] After his flight, opposition parties and defectors from the Party of Regions put together a parliamentary quorum in the Verkhovna Rada (the Ukrainian parliament), and voted on 22 February to remove Yanukovych from his post on the grounds that he was unable to fulfill his duties.[90][91][92] Arseniy Yatsenyuk was appointed by the Rada to serve as the head of a caretaker government until new presidential and parliament elections could be held. This new government was recognised internationally. Russian government and propaganda have described these events as a "coup d'état" and have said that the caretaker government was illegitimate,[93][94][95][96] while researchers consider the subsequent annexation of Crimea to be a true military coup, because the Russian military seized Crimea's parliament and government buildings and instigated the replacement of its government with Russian proxies.[97][98][99][100][101]

Annexation

Russian invasion of Crimea

The February 2014 revolution of Dignity that ousted Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych sparked a political crisis in Crimea, which initially manifested as demonstrations against the new interim Ukrainian government,[102] but rapidly escalated. In January 2014, the Sevastopol city council had already called for formation of "people's militia" units to "ensure firm defence" of the city from "extremism".[103]

On February 20 several buses with Crimean license plates were stopped at a pro-Maidan checkpoint in a town in Cherkasy oblast. Their passengers were violently intimidated and some buses were burned. This incident was subsequently used by Russian propaganda which made unsubstantiated claims that the passengers were killed in gruesome ways.[104]

The Verkhovna Rada of Crimea members called for an extraordinary meeting on 21 February. In response to Russian separatist sentiment, the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) said that it would "use severe measures to prevent any action taken against diminishing the territorial integrity and sovereignty of Ukraine".[note 2][clarification needed] The party with the largest number of seats in the Crimean parliament (80 of 100), the Party of Regions of Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych, did not discuss Crimean secession, and were supportive of an agreement between President Yanukovych[82] and Euromaidan activists to end the unrest that was struck on the same day in Kyiv.[106][107]

Russia was concerned that the new government avowedly committed to closer relations with the West put its strategic positions in Crimea at risk. On 22–23 February[note 3], Russian president Vladimir Putin[108] convened an all-night meeting with security services chiefs to discuss extrication of the deposed Ukrainian president, Viktor Yanukovych, and at the end of that meeting Putin had remarked that "we must start working on returning Crimea to Russia".[8][9] After that GRU and FSB began negotiating deals with local sympathizers to ensure that when the operation began there would be well‑armed "local self‑defense groups" on the streets for support.[11]: 11 On 23 February pro-Russian demonstrations were held in the Crimean city of Sevastopol.

Crimean prime minister Anatolii Mohyliov said that his government recognised the new provisional government in Kyiv, and that the Crimean autonomous government would carry out all laws passed by the Ukrainian parliament.[109] In Simferopol, following a pro-Russian demonstration the previous day where protesters had replaced the Ukrainian flag over the parliament with a Russian flag,[110] a pro-Euromaidan rally of between 5,000 and 15,000 was held in support of the new government, and demanding the resignation of the Crimean parliament; attendees waved Ukrainian, Tatar, and European Union flags.[111] Meanwhile, in Sevastopol, thousands protested against the new Ukrainian government, voted to establish a parallel administration, and created civil defence squads with the support of the Russian Night Wolves motorcycle club. Protesters waved Russian flags, chanted "Putin is our president!" and said they would refuse to further pay taxes to the Ukrainian state.[112][113] Russian military convoys were also alleged to be seen in the area.[113]

In Kerch, pro-Russian protesters attempted to remove the Ukrainian flag from atop city hall and replace it with the flag of Russia. Over 200 attended, waving Russian, orange-and-black St. George, and the Russian Unity party flags. Mayor Oleh Osadchy attempted to disperse the crowd and police eventually arrived to defend the flag. The mayor said "This is the territory of Ukraine, Crimea. Here's a flag of Crimea," but was accused of treason and a fight ensued over the flagpole.[114] On 24 February, more rallied outside the Sevastopol city state administration.[115] Pro-Russian demonstrators accompanied by neo-Cossacks demanded the election of a Russian citizen as mayor and hoisted Russian flags around the city administration; they also handed out leaflets to sign up for a self-defence militia, warning that the "Blue-Brown Europlague is knocking".[116]

Volodymyr Yatsuba, head of Sevastopol administration, announced his resignation, citing the "decision of the city's inhabitants" made at a pro-Russian rally, and while caretaker city administration initially leaned towards recognition of new Ukrainian government,[117] continued pressure from pro-Russian activists forced local authorities to concede.[118] Consequently, Sevastopol City Council illegally elected Alexei Chaly, a Russian citizen, as mayor. Under the law of Ukraine, it was not possible for Sevastopol to elect a mayor, as the Chairman of the Sevastopol City State Administration, appointed by the president of Ukraine, functions as its mayor.[119] A thousand protesters present chanted "A Russian mayor for a Russian city".[120]

On 25 February, several hundred pro-Russian protesters blocked the Crimean parliament demanding non-recognition of the central government of Ukraine and a referendum on Crimea's status.[121][122][123] On the same day, crowds gathered again outside Sevastopol's city hall on Tuesday as rumours spread that security forces could arrest Chaly, but police chief Alexander Goncharov said that his officers would refuse to carry out "criminal orders" issued by Kyiv. Viktor Neganov, a Sevastopol-based adviser to the Internal Affairs Minister, condemned the events in the city as a coup. "Chaly represents the interests of the Kremlin which likely gave its tacit approval," he said. Sevastopol City State Administration chairman Vladimir Yatsuba was booed and heckled on 23 February, when he told a pro-Russian rally that Crimea was part of Ukraine. He resigned the next day.[120] In Simferopol, the Regional State Administration building was blockaded with hundreds of protesters, including neo-Cossacks, demanding a referendum of separation; the rally was organized by the Crimean Front.[124]

On 26 February, near the Verkhovna Rada of Crimea building, 4,000–5,000 Crimean Tatars and supporters of the Euromaidan-Crimea movement faced 600–700 supporters of pro-Russian organizations and the Russian Unity Party.[125] Tatars leaders organised the demonstration in order to block the sitting of the Crimean parliament which is "doing everything to execute plans of separation of Crimea from Ukraine". Supreme Council Chairman Vladimir Konstantinov said that the Crimean parliament would not consider separation from Ukraine, and that earlier reports that parliament would hold a debate on the matter were provocations.[126][127] Tatars created self-defence groups, encouraged collaboration with Russians, Ukrainians, and people of other nationalities, and called for the protection of churches, mosques, synagogues, and other important sites.[128] By nightfall the Crimean Tatars had left; several hundred Russian Unity supporters rallied on.[129]

The new Ukrainian government's acting Internal Affairs Minister Arsen Avakov tasked Crimean law enforcement agencies not to provoke conflicts and to do whatever necessary to prevent clashes with pro-Russian forces; and he added "I think, that way – through a dialogue – we shall achieve much more than with standoffs".[130] New Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) chief Valentyn Nalyvaichenko requested that the United Nations provide around-the-clock monitoring of the security situation in Crimea.[131] Russian troops took control of the main route to Sevastopol on orders from Russian president Vladimir Putin. A military checkpoint, with a Russian flag and Russian military vehicles, was set up on the main highway between the city and Simferopol.[132]

Russian takeover

On 27 February, unmarked Russian forces in cooperation with local nationalist paramilitaries took over the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol, with Russian special forces[133] seizing the building of the Supreme Council of Crimea and the building of the Council of Ministers in Simferopol.[134] Russian flags were raised over these buildings[135] and barricades were erected outside them.[136] Pro-Russian forces also occupied several localities in Kherson Oblast on the Arabat Spit, which is geographically a part of Crimea.

Whilst the "little green men" were occupying the Crimean parliament building, the parliament held an emergency session.[137][138] It voted to terminate the Crimean government, and replace Prime Minister Anatolii Mohyliov with Sergey Aksyonov.[139] Aksyonov belonged to the Russian Unity party, which received 4% of the vote in the last election.[138] According to the Constitution of Ukraine, the prime minister of Crimea is appointed by the Supreme Council of Crimea in consultation with the president of Ukraine.[140][141] Both Aksyonov and speaker Vladimir Konstantinov stated that they viewed Viktor Yanukovych as the de jure president of Ukraine, through whom they were able to ask Russia for assistance.[142]

The parliament also voted to hold a referendum on greater autonomy set for 25 May. The troops had cut all of the building's communications, and took MPs' phones as they entered.[137][138] No independent journalists were allowed inside the building while the votes were taking place.[138] Some MPs said they were being threatened and that votes were cast for them and other MPs, even though they were not in the chamber.[138] Interfax-Ukraine reported "it is impossible to find out whether all the 64 members of the 100-member legislature who were registered as present at when the two decisions were voted on or whether someone else used the plastic voting cards of some of them" because due to the armed occupation of parliament it was unclear how many MPs were present.[143]

The head of parliament's information and analysis department, Olha Sulnikova, had phoned from inside the parliamentary building to journalists and had told them 61 of the registered 64 deputies had voted for the referendum resolution and 55 for the resolution to dismiss the government.[143] Donetsk People's Republic separatist Igor Girkin said in January 2015 that Crimean members of parliament were held at gunpoint, and were forced to support the annexation.[144] These actions were immediately declared illegal by the Ukrainian interim government.[145]

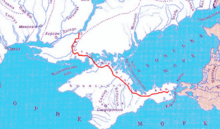

On the same day, more troops in unmarked uniforms, assisted this time by what appeared to be local Berkut riot police (as well as Russian troops from the 31st Separate Airborne Assault Brigade dressed in Berkut uniforms),[146] established security checkpoints on the Isthmus of Perekop and the Chonhar Peninsula, which separate Crimea from the Ukrainian mainland.[136][147][148][149][150] Within hours, Ukraine had been cut off from Crimea. Shortly afterwards, Ukrainian TV channels became unavailable for Crimean viewers, and some of them were replaced with Russian stations.

On 1 March 2014, Aksyonov said that he would exercise control of all Ukrainian military and security installations on the peninsula. He also asked Putin for "assistance in ensuring peace and tranquillity" in Crimea.[151] Putin promptly received authorisation from the Federation Council of Russia for a Russian military intervention in Ukraine until the "political-social situation in the country is normalized".[152][153] Putin's swift manoeuvre prompted protests of some Russian intelligentsia and demonstrations in Moscow against a Russian military campaign in Crimea. By 2 March, Russian troops moving from the country's naval base in Sevastopol and reinforced by troops, armour, and helicopters from mainland Russia exercised complete control over the Crimean Peninsula.[154][155][156] Russian troops operated in Crimea without insignia. On 3 March they blockaded Southern Naval Base.

On 4 March, Ukrainian General Staff said there were units of the 18th Motor Rifle Brigade, 31st Air Assault Brigade and 22nd Spetsnaz Brigade deployed and operating in Crimea, instead of Russian Black Sea Fleet personnel, which violated international agreements signed by Ukraine and Russia.[157][158] At a press conference on the same day, Russian president Vladimir Putin said that Russia had no plans to annex Crimea.[159] He also said that it had no plans to invade Ukraine, but that it might intervene if Russians in Ukraine were threatened.[159] This was part of a pattern of public denials of the ongoing Russian military operation.[159]

Numerous media reports and statements by the Ukrainian and foreign governments noted the identity of the unmarked troops as Russian soldiers, but Russian officials concealed the identity of their forces, claiming they were local "self-defence" units over whom they had no authority.[39] As late as 17 April, Russian foreign minister Sergey Lavrov said that there were no "excessive Russian troops" in Ukraine.[160] At the same press conference, Putin said of the peninsula that "only citizens themselves, in conditions of free expression of will and their security can determine their future".[161] Putin later acknowledged that he had ordered "work to bring Crimea back into Russia" as early as February.[40] He also acknowledged that in early March there were "secret opinion polls" held in Crimea, which, according to him, reported overwhelming popular support for Crimea's incorporation into Russia.[162]

Russia eventually admitted its troops' presence.[163] Defence Minister Sergey Shoygu said the country's military actions in Crimea were undertaken by forces of the Black Sea Fleet and were justified by "threat to lives of Crimean civilians" and danger of "takeover of Russian military infrastructure by extremists".[164][better source needed] Ukraine complained that by increasing its troop presence in Crimea, Russia violated the agreement under which it headquartered its Black Sea Fleet in Sevastopol[165] and violated the country's sovereignty.[166] The United States and United Kingdom accused Russia of breaking the terms of the Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances, by which Russia, the US, and the UK had reaffirmed their obligation to refrain from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of Ukraine.[167] The Russian government said the Budapest Memorandum[168] did not apply due to "circumstances resulting from the action of internal political or socio-economic factors".[169] In March 2015, retired Russian Admiral Igor Kasatonov stated that according to his information the Russian troop deployment in Crimea included six helicopter landings and three landings of an IL-76 with 500 people.[170][171]

Legal issues

| Part of a series on the |

| 2014 annexation of Crimea |

|---|

|

|

|

The obligations between Russia and Ukraine with regard to territorial integrity and the prohibition of the use of force are laid down in a number of multilateral or bilateral agreements to which Russia and Ukraine are signatories.[172][173][167][174]

Vladimir Putin said that Russian troops in the Crimean Peninsula were aimed "to ensure proper conditions for the people of Crimea to be able to freely express their will,"[175] whilst Ukraine and other nations argue that such intervention is a violation of Ukraine's sovereignty.[166]

In the 1994 Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances[168] Russia was among those who affirmed to respect the territorial integrity of Ukraine (including Crimea) and to refrain from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of Ukraine.[167][174] The 1997 Russian–Ukrainian Treaty on Friendship,[176] Cooperation, and Partnership again reaffirmed the inviolability of the borders between both states,[174] and required Russian forces in Crimea to respect the sovereignty of Ukraine, honor its legislation and not interfere in the internal affairs of the country.[177]

The Russian–Ukrainian Partition Treaty on the Status and Conditions of the Black Sea Fleet signed in 1997 and prolonged in 2010, determined the status of Russian military presence in Crimea and restricted their operations,[174] including requirement to show their "military identification cards" when crossing the international border and that operations beyond designated deployment sites was permitted only after coordination with Ukraine.[177] According to Ukraine usage of navigation stations and troop movements were improperly covered by the treaty and were violated many times as well as related court decisions. February's troop movements were in "complete disregard" of the treaty.[178][note 4]

According to the Constitution of Russia, the admission of new federal subjects is governed by federal constitutional law (art. 65.2).[180] Such a law was adopted in 2001, and it postulates that admission of a foreign state or its part into Russia shall be based on a mutual accord between the Russian Federation and the relevant state and shall take place pursuant to an international treaty between the two countries; moreover, it must be initiated by the state in question, not by its subdivision or by Russia.[181]

On 28 February 2014, Russian MP Sergey Mironov, along with other members of the Duma, introduced a bill to alter Russia's procedure for adding federal subjects. According to the bill, accession could be initiated by a subdivision of a country, provided that there is "absence of efficient sovereign state government in foreign state"; the request could be made either by subdivision bodies on their own or on the basis of a referendum held in the subdivision in accordance with corresponding national legislation.[182]

On 11 March 2014, both the Supreme Council of Crimea and the Sevastopol City Council adopted a declaration of independence, which stated their intent to declare independence and request full accession to Russia should the pro-Russian option receive the most votes during the scheduled status referendum. The declaration directly referred to the Kosovo independence precedent, by which the Albanian-populated Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija declared independence from Russia's ally Serbia as the Republic of Kosovo in 2008—a unilateral action Russia staunchly opposed. The Russian government used Kosovo independence precedent as a legal justification for the annexation of Crimea[183][184][185][186] Many analysts saw the Crimean declaration as an overt effort to pave the way for Crimea's annexation by Russia[187] and reject Russia's Kosovo precedent justification as being different compared to Crimea events,[188][189] comparing the annexation to the Nazi Germany's anschluss of Austria and Czechoslovak Sudetes instead.[190][191]

Crimean authorities' stated plans to declare independence from Ukraine made the Mironov bill unnecessary. On 20 March 2014, two days after the treaty of accession was signed, the bill was withdrawn by its initiators.[192][non-primary source needed]

At its meeting on 21–22 March, the Council of Europe's Venice Commission stated that the Mironov bill violated "in particular, the principles of territorial integrity, national sovereignty, non-intervention in the internal affairs of another state and pacta sunt servanda" and was therefore incompatible with international law.[193][194]

Crimean status referendum

On 27 February 2014, following the takeover of its building and replacement of Ukrainian-elected officials with Russian-controlled actors by Russian special forces,[195] the Supreme Council of Crimea voted to hold a referendum on 25 May, with the initial question as to whether Crimea should upgrade its autonomy within Ukraine.[196][non-primary source needed] The referendum date was later moved from 25 May to 30 March.[197] A Ukrainian court declared the referendum to be illegal.[198]

On 6 March, the Supreme Council moved the referendum date to 16 March and changed its scope to ask a new question: whether Crimea should apply to join Russia as a federal subject or restore the 1992 Crimean constitution within Ukraine, which the Ukrainian government had previously invalidated. This referendum, unlike one announced earlier, contained no option to maintain the status quo of governance under the 1998 constitution.[199] Ukraine's acting president, Oleksandr Turchynov, stated that "The authorities in Crimea are totally illegitimate, both the parliament and the government. They are forced to work under the barrel of a gun and all their decisions are dictated by fear and are illegal".[200]

On 14 March, the Crimean status referendum was deemed unconstitutional by the Constitutional Court of Ukraine,[201] and a day later, the Verkhovna Rada formally dissolved the Crimean parliament.[42] With a referendum looming, Russia massed troops near the Ukrainian eastern border,[202] likely to threaten escalation and stymie Ukraine's response.

The referendum was held despite the opposition from the Ukrainian government. Official results reported about 95.5% of participating voters in Crimea (turnout was 83%) were in favour of seceding from Ukraine and joining Russia.[50][203][204] Crimean Tatars mostly boycotted the referendum.[205] A report by Evgeny Bobrov, a member of the Russian President's Human Rights Council, suggested the official results were inflated and between 50 and 60% of Crimeans voted for the reunification with Russia, with the turnout of 30-50%, meaning that 15% to 30% of Crimeans eligible to vote voted for the Russian annexation (the support was higher in administratively separate Sevastopol).[195][41][206][207] According to a survey carried out by Pew Research Center in 2014, 54% of Crimean residents supported the right of regions to secede, 91% believed the referendum was free and fair and 88% believed that the government in Kyiv ought to recognize the results of the vote.[208]

The means by which the referendum was conducted were widely criticised by foreign governments[209] and in the Ukrainian and international press, with reports that anyone holding a Russian passport regardless of residency in Crimea was allowed to vote.[210] OSCE refused to send observers to the referendum, stating that invitation should have come from an OSCE member state in question (i.e. Ukraine), rather than local authorities.[211] Russia invited a group of observers from various European far-right political parties aligned with Putin, who stated the referendum was conducted in a free and fair manner.[212][213]

Proclamations of independence of the Republic of Crimea

The Republic of Crimea was short lived. On 17 March, following the official announcement of the referendum results, the Supreme Council of Crimea declared the formal independence of the Republic of Crimea, comprising the territories of both the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol, which was granted special status within the breakaway republic.[214] The Crimean parliament declared the "partial repeal" of Ukrainian laws and began nationalising private and Ukrainian state property located on the Crimean Peninsula, including Ukrainian ports[215] and property of Chornomornaftogaz.[216] Parliament also formally requested that the Russian government admit the breakaway republic into Russia,[217] with Sevastopol asking to be admitted as a "city of federal significance".[218] On the same day, the de facto Supreme Council renamed itself the State Council of Crimea,[219] declared the Russian ruble an official currency alongside the hryvnia,[220] and in June the Russian ruble became the only form of legal tender.[221]

Putin officially recognised the Republic of Crimea 'as a sovereign and independent state' by decree on 17 March.[222][223]

On 21 March the Republic of Crimea became a federal Subject of Russia.

Accession treaty and finalization of the annexation

The Treaty on Accession of the Republic of Crimea to Russia was signed between representatives of the Republic of Crimea (including Sevastopol, with which the rest of Crimea briefly unified) and the Russian Federation on 18 March 2014 to lay out terms for the immediate admission of the Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol as federal subjects of Russia and part of the Russian Federation.[224][225][note 5] On 19 March, the Russian Constitutional Court decided that the treaty is in compliance with the Constitution of Russia.[227] The treaty was ratified by the Federal Assembly and Federation Council by 21 March.[228] A Just Russia's Ilya Ponomarev was the only State Duma member to vote against the treaty.[229] The Republic of Crimea and the federal city of Sevastopol became the 84th and 85th federal subjects of Russia.[230]

During a controversial incident in Simferopol on 18 March, some Ukrainian sources said that armed gunmen that were reported to be Russian special forces allegedly stormed the base. This was contested by Russian authorities, who subsequently announced the arrest of an alleged Ukrainian sniper in connection with the killings,[231] but later denied the arrest had occurred.[232]

The two casualties had a joint funeral attended by both the Crimean and Ukrainian authorities, and both the Ukrainian soldier and Russian paramilitary "self-defence volunteer" were mourned together.[233] As of March 2014 the incident was under investigation by both the Crimean authorities and the Ukrainian military.[234][235]

In response to shooting, Ukraine's then acting defense minister Ihor Tenyukh authorised Ukrainian troops stationed in Crimea to use deadly force in life-threatening situations. This increased the risk of bloodshed during any takeover of Ukrainian military installations, yet the ensuing Russian operations to seize the remaining Ukrainian military bases and ships in Crimea did not bring new fatalities, although weapons were used and several people were injured. The Russian units involved in such operations were ordered to avoid usage of deadly force when possible. Morale among the Ukrainian troops, which for three weeks were blockaded inside their compounds without any assistance from the Ukrainian government, was very low, and the vast majority of them did not offer any real resistance.[236]

On 24 March, the Ukrainian government ordered the full withdrawal of all of its armed forces from Crimea.[237] Approximately 50% of the Ukrainian soldiers in Crimea had defected to the Russian military.[238][239] On 26 March the last Ukrainian military bases and Ukrainian Navy ships were captured by Russian troops.[240]

Occupation

On 27 March, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a non-binding resolution, which declared the Crimean referendum and subsequent status change invalid, by a vote of 100 to 11, with 58 abstentions and 24 absent.[241][242]

Crimea and Sevastopol switched to Moscow Time at 10 p.m. on 29 March.[243][244]

On 31 March, Russia unilaterally denounced the Kharkiv Pact[245] and Partition Treaty on the Status and Conditions of the Black Sea Fleet.[246] Putin cited "the accession of the Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol into Russia" and resulting "practical end of renting relationships" as his reason for the denunciation.[247] On the same day, he signed a decree formally rehabilitating the Crimean Tatars, who were ousted from their lands in 1944, and the Armenian, German, Greek, and Bulgarian minority communities in the region that Stalin also ordered removed in the 1940s.

Also on 31 March 2014, the Russian prime minister Dmitry Medvedev announced a series of programmes aimed at swiftly incorporating the territory of Crimea into Russia's economy and infrastructure. Medvedev announced the creation of a new ministry for Crimean affairs, and ordered Russia's top ministers who joined him there to make coming up with a development plan their top priority.[248] On 3 April 2014, the Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol became parts of Russia's Southern Military District.[citation needed] On 7 May 2015, Crimea switched its phone code system from the Ukrainian number system to the Russian number system.[249]

On 11 April, the Constitution of the Republic of Crimea and City Charter of Sevastopol were adopted by their respective legislatures,[250][251] coming into effect the following day in addition the new federal subjects were enumerated in a newly published revision of the Russian Constitution.[252][253]

On 14 April, Vladimir Putin announced that he would open a ruble-only account with Bank Rossiya and would make it the primary bank in the newly annexed Crimea as well as giving the right to service payments on Russia's $36 billion wholesale electricity market – which gave the bank $112 million annually from commission charges alone.[254]

Russia withdrew its forces from southern Kherson in December 2014.[255]

In July 2015, Russian prime minister, Dmitry Medvedev, declared that Crimea had been fully integrated into Russia.[256] Until 2016 these new subjects were grouped in the Crimean Federal District.

On 8 August 2016, Ukraine reported that Russia had increased its military presence along the demarcation line.[257] In response to this military buildup Ukraine also deployed more troops and resources closer to the border with Crimea.[258] The Pentagon has downplayed a Russian invasion of Ukraine, calling Russian troops along the border a regular military exercise.[259] On 10 August, Russia claimed two servicemen were killed in clashes with Ukrainian commandos, and that Ukrainian servicemen had been captured with a total of 40 kg of explosives in their possession.[260] Ukraine denied that the incident took place.[261]

Russian accounts claimed that Russian FSB detained "Ukrainian saboteurs" and "terrorists" near Armiansk. The ensuing gunfight left one FSB officer and a suspect dead. A number of individuals were detained, including Yevhen Panov, who is described by Russian sources as a Ukrainian military intelligence officer and leader of the sabotage group. The group was allegedly planning terror attacks on important infrastructure in Armiansk, Crimea.[262][263]

Ukrainian media reported that Panov was a military volunteer fighting in the east of the country, however he has more recently been associated with a charitable organization. Russia also claimed that the alleged border infiltration was accompanied by "heavy fire" from Ukrainian territory, resulting in the death of a Russian soldier.[262][263] The Ukrainian government called the Russian accusations "cynical" and "senseless" and argued that since Crimea was Ukrainian territory, it was Russia which "has been generously financing and actively supporting terrorism on Ukrainian territory".[264]

In 2017, a survey performed by the Centre for East European and International Studies showed that 85% of the non-Crimean Tatar respondents believed that if the referendum would be held again it would lead to the same or "only marginally different" results. Crimea was fully integrated into the Russian media sphere, and links with the rest of Ukraine were hardly existent.[265][266]

On 26 November 2018, lawmakers in the Ukraine Parliament overwhelmingly backed the imposition of martial law along Ukraine's coastal regions and those bordering Russia in response to the firing upon and seizure of Ukrainian naval ships by Russia near the Crimean Peninsula a day earlier. A total of 276 lawmakers in Kyiv backed the measure, which took effect on 28 November 2018 and was ended on 26 December.[267][268]

On 28 December 2018, Russia completed a high-tech security fence marking the de facto border between Crimea and Ukraine.[269]

In 2021, Ukraine launched the Crimea Platform, a diplomatic initiative aimed at protecting the rights of Crimean inhabitants and ultimately reversing the annexation of Crimea.[270]

Transition and aftermath

Economic implications

Initially after the annexation, salaries rose, especially those of government workers[citation needed]. This was soon offset by the increase in prices caused by the depreciation of the ruble. Wages were cut back by 30% to 70% after Russian authority became established[citation needed]. Tourism, previously Crimea's main industry, suffered in particular, down by 50% from 2014 in 2015.[271][272] Crimean agricultural yields were also significantly impacted by the annexation[citation needed]. Ukraine cut off supplies of water through the North Crimean Canal, which supplies 85% of Crimea's fresh water,[failed verification] causing the 2014 rice crop to fail, and greatly damaging the maize and soybean crops.[273] The annexation had a negative influence on Russians working in Ukraine and Ukrainians working in Russia.[274]

The number of tourists visiting Crimea in the 2014 season was lower than in the previous years due to a combination of "Western sanctions", ethical objections by Ukrainians, and the difficulty of getting there for Russians.[275] The Russian government attempted to stimulate the flow of tourists by subsidizing holidays in the peninsula for children and state workers from all Russia[276][277][better source needed] which worked mostly for state-owned hotels. In 2015, overall 3 million tourists visited Crimea according to official data, while before annexation it was around 5.5 million on average. The shortage is attributed mostly to stopped flow of tourists from Ukraine. Hotels and restaurants are also experiencing problems with finding enough seasonal workers, who were most arriving from Ukraine in the preceding years. Tourists visiting state-owned hotels were complaining mostly about low standard of rooms and facilities, some of them still unrepaired from Soviet times.[278]

According to the German newspaper Die Welt, the annexation of Crimea is economically disadvantageous for the Russian Federation. Russia will have to spend billions of euros a year to pay salaries and pensions. Moreover, Russia will have to undertake costly projects to connect Crimea to the Russian water supply and power system because Crimea has no land connection to Russia and at present (2014) gets water, gas and electricity from mainland Ukraine. This required building a bridge and a pipeline across the Kerch Strait. Also, Novinite claims that a Ukrainian expert told Die Welt that Crimea "will not be able to attract tourists".[279]

The then first Deputy to Minister of Finance of Russian Federation Tatyana Nesterenko said that the decision to annex Crimea was made by Vladimir Putin exclusively, without consulting Russia's Finance Ministry.[280]

The Russian business newspaper Kommersant expresses an opinion that Russia will not acquire anything economically from "accessing" Crimea, which is not very developed industrially, having just a few big factories, and whose yearly gross product is only $4 billion. The newspaper also says that everything from Russia will have to be delivered by sea, higher costs of transportation will result in higher prices for everything, and to avoid a decline in living standards Russia will have to subsidise Crimean people for a few months. In total, Kommersant estimates the costs of integrating Crimea into Russia in $30 billion over the next decade, i.e. $3 billion per year.[281]

Western oil experts[who?]estimate that Russia's seizing of Crimea, and the associated control of an area of Black Sea more than three times its land area gives it access to oil and gas reserves potentially worth trillions of dollars.[282] It also deprives Ukraine of its chances of energy independence. Moscow's acquisition may alter the route along which the South Stream pipeline would be built, saving Russia money, time and engineering challenges[citation needed]. It would also allow Russia to avoid building in Turkish territorial waters, which was necessary in the original route to avoid Ukrainian territory.[283] This pipeline was later canceled in favour of TurkStream, however.

The Russian Federal Service for Communications (Roskomnadzor) warned about a transition period as Russian operators have to change the numbering capacity and subscribers. Country code will be replaced from the Ukrainian +380 to Russian +7. Codes in Crimea start with 65, but in the area of "7" the 6 is given to Kazakhstan which shares former Soviet Union +7 with Russia, so city codes have to change. The regulator assigned 869 dialling code to Sevastopol and the rest of the peninsula received a 365 code.[284] At the time of the unification with Russia, telephone operators and Internet service providers in Crimea and Sevastopol are connected to the outside world through the territory of Ukraine.[285] Minister of Communications of Russia, Nikolai Nikiforov announced on his Twitter account that postal codes in Crimea will now have six-figures: to the existing five-digit number the number two will be added at the beginning. For example, the Simferopol postal code 95000 will become 295000.[286]

In the area that now forms the border between Crimea and Ukraine mining the salt lake inlets from the sea that constitute the natural borders, and in the spit of land left over stretches of no-man's-land with wire on either side was created.[287] On early June that year Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev signed a Government resolution No.961[288] dated 5 June 2014 establishing air, sea, road and railway checkpoints. The adopted decisions create a legal basis for the functioning of a checkpoint system at the Russian state border in the Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol.[289][third-party source needed]

In the year following the annexation, armed men seized various Crimean businesses, including banks, hotels, shipyards, farms, gas stations, a bakery, a dairy, and Yalta Film Studio.[290][291][292] Russian media have noted this trend as "returning to the 90's," which is perceived as a period of anarchy and rule of gangs in Russia.[293]

After 2014 the Russian government invested heavily in the peninsula's infrastructure—repairing roads, modernizing hospitals and building the Crimean Bridge that links the peninsula to the Russian mainland. Development of new sources of water was undertaken, with huge difficulties, to replace closed Ukrainian sources.[294] In 2015, the Investigative Committee of Russia announced a number of theft and corruption cases in infrastructure projects in Crimea, for example; spending that exceeded the actual accounted costs by a factor of three. A number of Russian officials were also arrested for corruption, including head of federal tax inspection.[295]

(According to February 2016 official Ukrainian figures) after Russia's annexation 10% of Security Service of Ukraine personnel left Crimea; accompanied by 6,000 of the pre-annexation 20,300 people strong Ukrainian army.[296]

As result of the disputed political status of Crimea, Russian mobile operators never expanded their operations into Crimea and all mobile services are offered on the basis of "internal roaming," which caused significant controversy inside Russia. Telecoms however argued that expanding coverage to Crimea will put them at risk of Western sanctions and, as result, they will lose access to key equipment and software, none of which is produced locally.[297][298]

The first five years of Crimean occupation cost Russia over $20 billion, roughly equal to two years of Russia's entire education budget.[299]

Human rights situation

According to the United Nations and multiple NGOs, Russia is responsible for multiple human rights abuses, including torture, arbitrary detention, forced disappearances and instances of discrimination, including persecution of Crimean Tatars in Crimea since the illegal annexation.[300][301] The UN Human Rights Office has documented multiple human rights violations in Crimea. Noting that minority Crimean Tatars have been disproportionately affected.[302][303] In December 2016, the UN General Assembly voted on a resolution on human rights in occupied Crimea. It called on the Russian Federation "to take all measures necessary to bring an immediate end to all abuses against residents of Crimea, in particular reported discriminatory measures and practices, arbitrary detentions, torture and other cruel, inhumane or degrading treatment, and to revoke all discriminatory legislation". It also urged Russia to "immediately release Ukrainian citizens who were unlawfully detained and judged without regard for elementary standards of justice".[304]

After the annexation, Russian authorities banned Crimean Tatar organizations, filed criminal charges against Tatar leaders and journalists, and targeted the Tatar population. The Atlantic Council have described this as the practice of collective punishment, and therefore as a war crime prohibited under international humanitarian law and Geneva convention.[305][better source needed]

In March 2014, Human Rights Watch reported that pro-Ukrainian activists and journalists had been attacked, abducted, and tortured by "self-defense" groups.[306] Some Crimeans were simply "disappeared" with no explanation.[307]

On 9 May 2014, the new "anti-extremist" amendment to the Criminal Code of Russia, passed in December 2013, came into force. Article 280.1 designated incitement of violation of territorial integrity of the Russian Federation[308] (incl. calls for secession of Crimea from Russia[309]) as a criminal offense in Russia, punishable by a fine of 300 thousand roubles or imprisonment up to 3 years. If such statements are made in public media or the internet, the punishment could be obligatory works up to 480 hours or imprisonment up to five years.[308]

According to a report released on the Russian government-run President of Russia's Council on Civil Society and Human Rights website, Tatars who were opposed to Russian rule have been persecuted, Russian law restricting freedom of speech has been imposed, and the new Russian authorities "liquidated" the Kyiv Patriarchate Orthodox church on the peninsula.[310][41] The Crimean Tatar television station was also shut down by the Russian authorities.[307]

On 16 May the new Russian authorities of Crimea issued a ban on the annual commemorations of the anniversary of the deportation of the Crimean Tatars by Stalin in 1944, citing "possibility of provocation by extremists" as a reason.[311] Previously, when Crimea was controlled by Ukraine, these commemorations had taken place every year. The Russian-installed Crimean authorities also banned Mustafa Dzhemilev, a human rights activist, Soviet dissident, member of the Ukrainian parliament, and former chairman of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatars from entering Crimea.[312] Additionally, Mejlis reported, that officers of Russia's Federal Security Service (FSB) raided Tatar homes in the same week, on the pretense of "suspicion of terrorist activity".[313] The Tatar community eventually did hold commemorative rallies in defiance of the ban.[312][313] In response Russian authorities flew helicopters over the rallies in an attempt to disrupt them.[314]

In May 2015, a local activist, Alexander Kostenko, was sentenced to four years in a penal colony. His lawyer, Dmitry Sotnikov, said that the case was fabricated and that his client had been beaten and starved. Crimean prosecutor Natalia Poklonskaya accused Kostenko of making Nazi gestures during the Maidan protests, and that they were judging "not just [Kostenko], but the very idea of fascism and Nazism, which are trying to raise their head once again". Sotnikov responded that "There are fabricated cases in Russia, but rarely such humiliation and physical harm. A living person is being tortured for a political idea, to be able to boast winning over fascism".[315] In June 2015, Razom released a report compiling human rights abuses in Crimea.[316][317] In its 2016 annual report, the Council of Europe made no mention of human rights abuses in Crimea because Russia had not allowed its monitors to enter.[318]

In February 2016 human rights defender Emir-Usein Kuku from Crimea was arrested and accused of belonging to the Islamist organization Hizb ut-Tahrir although he denies any involvement in this organization. Amnesty International has called for his immediate release.[319][320]

On 24 May 2014, Ervin Ibragimov, a former member of the Bakhchysarai Town Council and a member of the World Congress of Crimean Tatars went missing. CCTV footage from a camera at a nearby shop documents that Ibragimov had been stopped by a group of men and that he is briefly speaking to the men before being forced in their van.[321] According to the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group Russian authorities refuse to investigate the disappearance of Ibragimov.[322]

In May 2018 Server Mustafayev, the founder and coordinator of the human rights movement Crimean Solidarity was imprisoned by Russian authorities and charged with "membership of a terrorist organisation". Amnesty International and Front Line Defenders demand his immediate release.[323][324]

On 12 June 2018, Ukraine lodged a memorandum weighing about 90 kg, consisting of 17,500 pages of text in 29 volumes to the UN's International Court of Justice about racial discrimination by Russian authorities in occupied Crimea and state financing of terrorism by Russian Federation in Donbas.[325][326]

Between 2015 and 2019 over 134,000 people living in Crimea applied for and were issued Ukrainian passports.[327]

Crimean public opinion

Prior to Russian occupation, support for joining Russia was 23% in a 2013 poll, down from 33% in 2011.[328] A joint survey by American government agency Broadcasting Board of Governors and polling firm Gallup was taken during April 2014.[329] It polled 500 residents of Crimea. The survey found that 82.8% of those polled believed that the results of the Crimean status referendum reflected the views of most residents of Crimea, whereas 6.7% said that it did not. 73.9% of those polled said that they thought that the annexation would have a positive impact on their lives, whereas 5.5% said that it would not. 13.6% said that they did not know.[329]

A comprehensive poll released on 8 May 2014 by the Pew Research Centre surveyed local opinions on the annexation.[330] Despite international criticism of 16 March referendum on Crimean status, 91% of those Crimeans polled thought that the vote was free and fair, and 88% said that the Ukrainian government should recognise the results.[330]

In a survey completed in 2019 by a Russian company FOM 72% of surveyed Crimean residents said their lives have improved since annexation. At the same time only 39% Russians living in the mainland said the annexation was beneficial for the country as a whole which marks a significant drop from 67% in 2015.[331]

Whilst the Russian government actively cited local opinion polls to argue that the annexation was legitimate (i.e. supported by the population of the territory in question),[332][333] some authors have cautioned against using surveys concerning identities and support for the annexation conducted in "oppressive political environment" of Russian-held Crimea.[334][335]

Ukrainian response

Immediately after the treaty of accession was signed in March, the Ukrainian Ministry of Foreign Affairs summoned the Provisional Principal of Russia in Ukraine to present note verbale of protest against Russia's recognition of the Republic of Crimea and its subsequent annexation.[336] Two days later, the Verkhovna Rada condemned the treaty[337] and called Russia's actions "a gross violation of international law". The Rada called on the international community to avoid recognition of the "so-called Republic of Crimea" or the annexation of Crimea and Sevastopol by Russia as new federal subjects.

On 15 April 2014, the Verkhovna Rada declared the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol to be under "provisional occupation" by the Russian military[338] and imposed travel restrictions on Ukrainians visiting Crimea.[339] The territories were also deemed "inalienable parts of Ukraine" subject to Ukrainian law. Among other things, the special law approved by the Rada restricted foreign citizens' movements to and from the Crimean Peninsula and forbade certain types of entrepreneurship.[340] The law also forbade activity of government bodies formed in violation of Ukrainian law and designated their acts as null and void.[341][better source needed]

Ukrainian authorities greatly reduced the volume of water flowing into Crimea via the North Crimean Canal due to huge debt for water supplied in the previous year, threatening the viability of the peninsula's agricultural crops, which are heavily dependent on irrigation.[343][344]

The Ukrainian National Council for TV and Radio Broadcasting instructed all cable operators on 11 March 2014 to stop transmitting a number of Russian channels, including the international versions of the main state-controlled stations, Russia-1, Channel One and NTV, as well as news channel Russia-24.[345]

In March 2014, activists began organising flash mobs in supermarkets to urge customers not to buy Russian goods and to boycott Russian gas stations, banks, and concerts. In April 2014, some cinemas in Kyiv, Lviv, and Odesa began shunning Russian films.[346]

On 2 December 2014, Ukraine created a Ministry of Information Policy, with one of its goals being, according to first Minister of Information, Yuriy Stets, to counteract "Russian information aggression".[347]

In December 2014, Ukraine halted all train and bus services to Crimea.[348]

On 16 September 2015, the Ukrainian parliament voted for the law that sets 20 February 2014 as the official date of the Russian temporary occupation of the Crimean Peninsula.[349][350] On 7 October 2015, the president of Ukraine signed the law into force.[351]

The Ministry of Temporarily Occupied Territories and IDPs was established by the Ukrainian government on 20 April 2016 to manage occupied parts of Donetsk, Luhansk and Crimea regions affected by Russian military intervention of 2014.[352] By 2015, the number of IDPs registered in Ukraine who had fled from Russian-occupied Crimea was 50,000.[353]

Russian response

In a poll published on 24 February 2014 by the state-owned Russian Public Opinion Research Center, only 15% of those Russians polled said 'yes' to the question: "Should Russia react to the overthrow of the legally elected authorities in Ukraine?"[354]

The State Duma Committee on Commonwealth of Independent States Affairs, headed by Leonid Slutsky, visited Simferopol on 25 February 2014 and said: "If the parliament of the Crimean autonomy or its residents express the wish to join the Russian Federation, Russia will be prepared to consider this sort of application. We will be examining the situation and doing so fast".[355] They also stated that in the event of a referendum for the Crimea region joining the Russian Federation, they would consider its results "very fast".[356] Later Slutsky announced that he was misunderstood by the Crimean press, and no decision regarding simplifying the process of acquiring Russian citizenship for people in Crimea had been made yet.[357] He also added that if "fellow Russian citizens are in jeopardy, you understand that we do not stay away".[358] On 25 February, in a meeting with Crimean politicians, he stated that Viktor Yanukovych was still the legitimate president of Ukraine.[359] That same day, the Russian Duma announced it was determining measures so that Russians in Ukraine who "did not want to break from the Russian World" could acquire Russian citizenship.[360]

On 26 February, Russian president Vladimir Putin ordered the Russian Armed Forces to be "put on alert in the Western Military District as well as units stationed with the 2nd Army Central Military District Command involved in aerospace defence, airborne troops and long-range military transport". Despite media speculation that this was in reaction to the events in Ukraine, Russian Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu said it was for reasons separate from the unrest in Ukraine.[361] On 27 February 2014, the Russian government dismissed accusations that it was in violation of the basic agreements regarding the Black Sea Fleet: "All movements of armored vehicles are undertaken in full compliance with the basic agreements and did not require any approvals".[362]

On 27 February, the Russian governing agencies presented the new law project on granting citizenship.[363]

The Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs called on the West and particularly NATO to "abandon the provocative statements and respect the neutral status of Ukraine".[364] In its statement, the ministry claims that the agreement on settlement of the crisis, which was signed on 21 February and was witnessed by foreign ministries from Germany, Poland and France had to this date, not been implemented[364] (Vladimir Lukin from Russia had not signed it[365]).

On 28 February, according to ITAR-TASS, the Russian Ministry of Transport discontinued further talks with Ukraine in regards to the Crimean Bridge project.[366] However, on 3 March Dmitry Medvedev, then Prime Minister of Russia, signed a decree creating a subsidiary of Russian Highways (Avtodor) to build a bridge at an unspecified location along the Kerch Strait.[367][368][369]

On Russian social networks, there was a movement to gather volunteers who served in the Russian army to go to Ukraine.[370] Many political researchers consider that after the annexation a social period in Russia coined as "Crimean consensus" begun, during which the "Rally 'round the flag" effect was observed in the population.[371]

On 28 February, President Putin stated in telephone calls with key EU leaders that it was of "extreme importance of not allowing a further escalation of violence and the necessity of a rapid normalisation of the situation in Ukraine".[372] Already on 19 February the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs had referred to the Euromaidan revolution as the "Brown revolution".[373][374]

In Moscow, on 2 March, an estimated 27,000 rallied in support of the Russian government's decision to intervene in Ukraine.[375] The rallies received considerable attention on Russian state TV and were officially approved by the government.[375]

Meanwhile, on 1 March, five people who were picketing next to the Federation Council building against the invasion of Ukraine were arrested.[376] The next day about 200 people protested at the building of the Russian Ministry of Defence in Moscow against Russian military involvement.[377] About 500 people also gathered to protest on the Manezhnaya Square in Moscow, and the same number of people on the Saint Isaac's Square in Saint Petersburg.[378] On 2 March, about eleven protesters demonstrated in Yekaterinburg against Russian involvement, with some wrapped in the Ukrainian flag.[379] Protests were also held in Chelyabinsk on the same day.[380] Opposition to the military intervention was also expressed by rock musician Andrey Makarevich, who wrote in particular: "You want war with Ukraine? It will not be the way it was with Abkhazia: the folks on the Maidan have been hardened and know what they are fighting for – for their country, their independence. ... We have to live with them. Still neighborly. And preferably in friendship. But it's up to them how they want to live".[381] The Professor of the Department of Philosophy at the Moscow State Institute of International Relations Andrey Zubov was fired for his article in Vedomosti, criticising Russian military intervention.[382]

On 2 March, one Moscow resident protested against Russian intervention by holding a "Stop the war" banner, but he was immediately harassed by passers-by. Police then proceeded to arrest him. A woman came forward with a fabricated charge against him, of beating up a child; however, her claim, due to lack of a victim and obviously false, was ignored by the police.[383] Andrei Zubov, a professor at the Moscow State Institute of International Relations, who compared Russian actions in Crimea to the 1938 Annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany, was threatened. Alexander Chuyev, the leader of the pro-Kremlin Spravedlivaya Rossiya party, also objected to Russian intervention in Ukraine. Boris Akunin, a popular Russian writer, predicted that Russia's moves would lead to political and economic isolation.[383]

President Putin's approval rating among the Russian public increased by nearly 10% since the crisis began, up to 71.6%, the highest in three years, according to a poll conducted by the All-Russian Center for Public Opinion Research, released on 19 March.[385][386] Additionally, the same poll showed that more than 90% of Russians supported unification with the Crimean Republic.[385] According to a 2021 study in the American Political Science Review, "three quarters of those who rallied to Putin after Russia annexed Crimea were engaging in at least some form of dissembling and that this rallying developed as a rapid cascade, with social media joining television in fueling perceptions this was socially desirable".[387]

On 4 March, at a press conference in Novo-Ogaryovo, President Putin expressed his view on the situation that if a revolution took place in Ukraine, it would be a new country with which Russia had not concluded any treaties.[388] He offered an analogy with the events of 1917 in Russia, when as a result of the revolution the Russian Empire fell apart and a new state was created.[388] However, he stated Ukraine would still have to honour its debts.

Russian politicians speculated that there were already 143,000 Ukrainian refugees in Russia.[389] The Ukrainian Ministry of Foreign Affairs refuted those claims of refugee increases in Russia.[390] At a briefing on 4 March 2014, the director of the department of information policy of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine Yevhen Perebiynis said that Russia was misinforming its own citizens as well as the entire international community to justify its own actions in the Crimea.[391]

On 5 March, an anchor of the Russian-controlled TV channel RT America, Abby Martin, criticized her employer's biased coverage of the military invervention.[392][393] Also on 5 March 2014, another RT America anchor, Liz Wahl, of the network's Washington, DC bureau, resigned on air, explaining that she could not be "part of a network that whitewashes the actions of Putin" and citing her Hungarian ancestry and the memory of the Soviet repression of the Hungarian Uprising as a factor in her decision.[394]

In early March, Igor Andreyev, a 75-year-old survivor of the Siege of Leningrad, attended an anti-war rally against the Russian intervention in Crimea and was holding a sign that read "Peace to the World". The riot police arrested him, and a local pro-government lawyer then accused him of being a supporter of "fascism". The retiree, who lived on a 6,500-ruble monthly pension, was fined 10,000 rubles.[395]

Prominent dissident Mikhail Khodorkovsky said that Crimea should stay within Ukraine with broader autonomy.[396]

Tatarstan, a republic within Russia populated by Volga Tatars, has sought to alleviate concerns about the treatment of Tatars by Russia, as Tatarstan is an oil-rich and economically successful republic in Russia.[397] On 5 March, President of Tatarstan Rustam Minnikhanov signed an agreement on co-operation between Tatarstan and the Aksyonov government in Crimea that implied collaboration between ten government institutions as well as significant financial aid to Crimea from Tatarstan businesses.[397] On 11 March, Minnikhanov was in Crimea on his second visit and attended as a guest in the Crimean parliament chamber during the vote on the declaration of sovereignty pending 16 March referendum.[397] The Tatarstan's Mufti Kamil Samigullin invited Crimean Tatars to study in madrasas in Kazan, and declared support for their "brothers in faith and blood".[397] Mustafa Dzhemilev, a former leader of the Crimean Tatar Majlis, believed that forces that were suspected to be Russian forces should leave the Crimean Peninsula,[397] and asked the UN Security Council to send peacekeepers into the region.[398]

On 15 March, thousands of protesters (estimates varying from 3,000 by official sources up to 50,000 claimed by the opposition) in Moscow marched against Russian involvement in Ukraine, many waving Ukrainian flags.[399] At the same time, a pro-government (and pro-referendum) rally occurred across the street, counting in the thousands as well (officials claiming 27,000 with the opposition claiming about 10,000).

In February 2015, the leading independent Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta obtained documents,[400] allegedly written by oligarch Konstantin Malofeev and others, which provided the Russian government with a strategy in the event of Viktor Yanukovych's removal from power and the break-up of Ukraine, which were considered likely. The documents outline plans for annexation of Crimea and the eastern portions of the country, closely describing the events that actually followed after Yanukovych's fall. The documents also describe plans for a public relations campaign that would seek to justify Russian actions.[401][402][403]

In June 2015 Mikhail Kasyanov stated that all Russian Duma decisions on Crimea annexation were illegal from the international point of view and the annexation was provoked by false accusations of discrimination of Russian nationals in Ukraine.[404]

As of January 2019, Arkady Rotenberg through his Stroygazmontazh LLC and his companies building the Crimean Bridge along with Nikolai Shamalov and Yuri Kovalchuk through their Rossiya Bank have become the most important investors in Russia's development of the annexed Crimea.[405]

International response

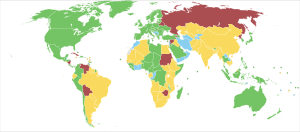

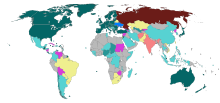

There has been a range of international reactions to the annexation. In March 2014, the UN General Assembly passed a non-binding resolution 100 in favour, 11 against and 58 abstentions in the 193-nation assembly that declared Crimea's Moscow-backed referendum invalid.[406] In a move supported by the Lithuanian president,[407] the United States government imposed sanctions against persons they deem to have violated or assisted in the violation of Ukraine's sovereignty.[408] The European Union suspended talks with Russia on economic and visa-related matters, and is considering more stringent sanctions against Russia in the near future, including asset freezes.[409][410] while Japan announced sanctions which include suspension of talks relating to military, space, investment, and visa requirements.[411] The United Kingdom qualified the referendum vote in Crimea of being "farcical", "illegal" and "illegitimate".[412]

Ukraine and other countries claim that Russia has signed a number of treaties guaranteeing Ukrainian territorial integrity. These include the 1991 Belavezha Accords that established the Commonwealth of Independent States, the 1975 Helsinki Accords, the 1994 Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances[413] and the 1997 Treaty on friendship, cooperation and partnership between the Russian Federation and Ukraine.[172][173][414]

The European Commission decided on 11 March 2014 to enter into a full free-trade agreement with Ukraine within the year.[415] On 12 March, the European Parliament rejected the upcoming referendum on independence in Crimea, which they saw as manipulated and contrary to international and Ukrainian law.[416] The G7 bloc of developed nations (the G8 minus Russia) made a joint statement condemning Russia and announced that they would suspend preparations for the planned G8 summit in Sochi in June.[417][418] NATO condemned Russia's military escalation in Crimea and stated that it was a breach of international law[419] while the Council of Europe expressed its full support for the territorial integrity and national unity of Ukraine.[420] The Visegrád Group has issued a joint statement urging Russia to respect Ukraine's territorial integrity and for Ukraine to take into account its minority groups to not further break fragile relations. It has urged for Russia to respect Ukrainian and international law and in line with the provisions of the 1994 Budapest Memorandum.[421]

China said "We respect the independence, sovereignty and territorial integrity of Ukraine". A spokesman restated China's belief of non-interference in the internal affairs of other nations and urged dialogue.[422][423]

The Indian government called for a peaceful resolution of the situation.[424] Both Syria and Venezuela openly support Russian military action. Syrian president Bashar al-Assad said that he supports Putin's efforts to "restore security and stability in the friendly country of Ukraine", while Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro condemned Ukraine's "ultra-nationalist" coup.[425][426] Sri Lanka described Yanukovych's removal as unconstitutional and considered Russia's concerns in Crimea as justified.[427]

Polish prime minister Donald Tusk called for a change in EU energy policy as Germany's dependence on Russian gas poses risks for Europe.[428]

On 13 March 2014, German Chancellor Angela Merkel warned the Russian government it risks massive damage to Russia, economically and politically, if it refuses to change course on Ukraine,[429] though close economic links between Germany and Russia significantly reduce the scope for any sanctions.[430]

After Russia moved to formally incorporate Crimea, some worried whether it may do the same in other regions.[431] US deputy national security advisor Tony Blinken said that the Russian troops massed on the eastern Ukrainian border may be preparing to enter the country's eastern regions. Russian officials stated that Russian troops would not enter other areas.[431] US Air Force Gen. Philip M. Breedlove, NATO's supreme allied commander in Europe, warned that the same troops were in a position to take over the separatist Russian-speaking Moldovan province of Transnistria.[431] President of Moldova Nicolae Timofti warned Russia with not attempting to do this to avoid damaging its international status further.[432][433]

On 9 April, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe deprived Russia of voting rights.[434]

On 14 August, while visiting Crimea, Vladimir Putin ruled out pushing beyond Crimea. He undertook to do everything he could to end the conflict in Ukraine, saying Russia needed to build calmly and with dignity, not by confrontation and war which isolated it from the rest of the world.[435]

United Nations resolutions

On 15 March 2014, a US-sponsored resolution that went to a vote in the UN Security Council to reaffirm that council's commitment to Ukraine's "sovereignty, independence, unity and territorial integrity" was not approved. Though a total of 13 council members voted in favour of the resolution and China abstained, Russia vetoed the resolution.[436]