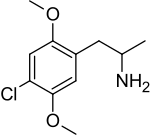

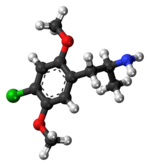

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-chloroamphetamine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | DOC; 2,5-Dimethoxy-4-chloroamphetamine; 4-Chloro-2,5-dimethoxyamphetamine |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.215.939 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C11H16ClNO2 |

| Molar mass | 229.70 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-chloroamphetamine (DOC) is a psychedelic drug of the phenethylamine, amphetamine, and DOx families. It was presumably first synthesized by Alexander Shulgin, and was described in his book PiHKAL (Phenethylamines i Have Known And Loved).[2]

Chemistry

[edit]DOC is a substituted alpha-methylated phenethylamine, a class of compounds commonly known as amphetamines. The phenethylamine equivalent (lacking the alpha-methyl group) is 2C-C. DOC has a stereocenter and (R)-(−)-DOC is the more active stereoisomer.

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]Actions

[edit]| Target | Affinity (Ki, nM) |

|---|---|

| 5-HT1A | >9,200 (Ki) >10,000 (EC50) <10% (Emax) |

| 5-HT1B | ND |

| 5-HT1D | ND |

| 5-HT1E | ND |

| 5-HT1F | ND |

| 5-HT2A | 1.4–4.0 (Ki) 2.9–11 (EC50) 81–102% (Emax) |

| 5-HT2B | 32 |

| 5-HT2C | 2–3.6 (Ki) 15 (EC50) 97% (Emax) |

| 5-HT3 | ND |

| 5-HT4 | ND |

| 5-HT5A | ND |

| 5-HT6 | ND |

| 5-HT7 | ND |

| α1A–α1D | ND |

| α2A–α2C | ND |

| β1–β3 | ND |

| D1–D5 | ND |

| TAAR1 | >1,000 |

| SERT | >10,000 (Ki) >8,600 (IC50) Minimal (EC50) |

| NET | >7,700 (Ki) >8,400 (IC50) Minimal (EC50) |

| DAT | >10,000 (Ki) >10,000 (IC50) Minimal (EC50) |

| Notes: The smaller the value, the more avidly the drug binds to the site. All proteins are human unless otherwise specified. Refs: [3][4][5][6] | |

DOC acts as a serotonin 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptor agonist. Its psychedelic effects are mediated via its actions on the 5-HT2A receptor.[citation needed]

The drug is inactive as a monoamine releasing agent and reuptake inhibitor.[5]

Effects

[edit]DOC has shown reinforcing effects, including conditioned place preference (CPP) and self-administration, in rodents similarly to methamphetamine.[7] This is analogous to other findings in which various 2C and NBOMe drugs have been found to produce dopaminergic elevations and reinforcing effects in rodents.[8][9][10][11][12][13][14] Conversely however, in contrast to amphetamines like (–)-cathinone but similarly to mescaline, DOM has shown no stimulant-like or reinforcing effects in rhesus monkeys.[15][16][17][18]

Dosage

[edit]A normal average dose of DOC ranges from 0.2–7.0 mg[19] the former producing threshold effects, and the latter producing extremely strong effects. Onset of the drug is 1–3 hours, peak and plateau at 4–8 hours, and a gradual come down with residual stimulation at 9-20h. After effects can last well into the next day.[19][20]

Effects

[edit]Unlike simple amphetamines, DOC is considered a chemical that influences cognitive and perception processes of the brain. The strongest supposed effects include open and closed eye visuals, increased awareness of sound and movement, and euphoria. In the autobiography PiHKAL, Alexander Shulgin included a description of DOC as "an archetypal psychedelic" (#64); its presumed full-range visual, audio, physical, and mental effects show exhilarating clarity, and some overwhelming, humbling, and "composting"/interweaving effects.[20]

Dangers

[edit]Very little data exists about the toxicity of DOC. In April 2013, a case of death due to DOC was reported. The source does not specify whether the drug alone caused the death.[21] In 2014, a death was reported in which DOC was directly implicated as the sole causative agent in the death of a user. The autopsy indicated pulmonary edema and a subgaleal hemorrhage.[22]

Detection in biological specimens

[edit]DOC may be quantitated in blood, plasma or urine by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry or liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients or to provide evidence in a medicolegal death investigation. Blood or plasma DOC concentrations are expected to be in a range of 1–10 μg/L in persons using the drug recreationally, >20 μg/L in intoxicated patients and >100 μg/L in victims of acute overdosage.[23]

Popularity

[edit]Although rare on the black market, it has been available in bulk and shipped worldwide by select elite "Grey Market" Research Chemical suppliers for several years. Sales of DOC on blotting paper and in capsules was reported in late 2005 and again in late 2007. According to the DEA's Microgram from December 2007, the Concord Police Department in Contra Costa County, California, in the US, seized "a small piece of crudely lined white blotter paper without any design, suspected LSD 'blotter acid'". They added "Unusually, the paper appeared to be hand-lined using two pens, in squares measuring approximately 6 x 6 millimeters. The paper displayed fluorescence when irradiated at 365 nanometers; however, color testing for LSD with para-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde (Ehrlich's reagent) was negative. Analysis of a methanol extract by GC/MS indicated not LSD but rather DOC (not quantitated but a high loading based on the TIC)".[24] DOC is sometimes misrepresented as LSD by unscrupulous dealers. This is particularly dangerous, as DOC is not known to have the safety profile of LSD. It can be particularly unsafe, in comparison to LSD, for those suffering from hypertension, as amphetamine compounds are known to cause sharp increases in systolic blood pressure.

Drug prohibition laws

[edit]Canada

[edit]Listed as a Schedule 1[25] as it is an analogue of amphetamine.[26] The CDSA was updated as a result of the Safe Streets Act changing amphetamines from Schedule 3 to Schedule 1.[27]

Australia

[edit]Unscheduled but can be controlled as schedule II as an analogue of DOB.[28]

China

[edit]As of October 2015 DOC is a controlled substance in China.[29]

New Zealand

[edit]Scheduled.[28]

Denmark

[edit]Denmark added DOC to the list of Schedule I controlled substances as of 8.4.2007.[28]

Germany

[edit]Scheduled in Anlage I since 22.1.2010.[28]

Sweden

[edit]Sveriges riksdag added DOC to schedule I ("substances, plant materials and fungi which normally do not have medical use") as narcotics in Sweden as of Aug 30, 2007, published by Medical Products Agency in their regulation LVFS 2007:10 listed as DOC, 4-klor-2,5-dimetoxi-amfetamin.[30] DOC was first classified by Sveriges riksdags health ministry Statens folkhälsoinstitut as "health hazard" under the act Lagen om förbud mot vissa hälsofarliga varor (translated Act on the Prohibition of Certain Goods Dangerous to Health) as of Jul 1, 2004, in their regulation SFS 2004:486 listed as 4-klor-2,5-dimetoxiamfetamin (DOC).[31]

United Kingdom

[edit]Class A.[28]

United States

[edit]DOC is not scheduled or controlled at the federal level in the United States,[32] but the Department of Justice considers it to be an analogue of DOB[33] and, as such, possession or sale could be prosecuted under the Federal Analogue Act.[28] In December 2023, the US Drug Enforcement Administration issued a notice of proposed rulemaking that would classify both 2,5-dimethoxy-4-chloroamphetamine and 2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine as schedule I controlled substances.[34]

In the United States, the analogues DMA, DOB, and DOM are Schedule I controlled substances.

US State of Florida

[edit]DOC is a Schedule I controlled substance in the state of Florida making it illegal to buy, sell, or possess.[35]

United Nations

[edit]In December 2019, the UNODC announced scheduling recommendations placing DOC into Schedule I alongside another several research chemicals.[36]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Anvisa (2023-07-24). "RDC Nº 804 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 804 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 2023-07-25). Archived from the original on 2023-08-27. Retrieved 2023-08-27.

- ^ Shulgin A, Shulgin A (September 1991). PiHKAL: A Chemical Love Story. United States: Transform Press. p. 978. ISBN 0-9630096-0-5. Archived from the original on 3 January 2010. Retrieved 30 November 2009.

- ^ "PDSP Database". UNC (in Zulu). Retrieved 1 February 2025.

- ^ Liu T. "BindingDB BDBM50013000 CHEMBL8100". BindingDB. Retrieved 1 February 2025.

- ^ a b Eshleman AJ, Forster MJ, Wolfrum KM, Johnson RA, Janowsky A, Gatch MB (March 2014). "Behavioral and neurochemical pharmacology of six psychoactive substituted phenethylamines: mouse locomotion, rat drug discrimination and in vitro receptor and transporter binding and function". Psychopharmacology (Berl). 231 (5): 875–888. doi:10.1007/s00213-013-3303-6. PMC 3945162. PMID 24142203.

- ^ Rudin D, Luethi D, Hoener MC, Liechti ME (2022). "Structure-activity Relation of Halogenated 2,5-Dimethoxyamphetamines Compared to their α‑Desmethyl (2C) Analogues". The FASEB Journal. 36 (S1). doi:10.1096/fasebj.2022.36.S1.R2121. ISSN 0892-6638.

- ^ Cha HJ, Jeon SY, Jang HJ, Shin J, Kim YH, Suh SK (May 2018). "Rewarding and reinforcing effects of 4-chloro-2,5-dimethoxyamphetamine and AH-7921 in rodents". Neurosci Lett. 676: 66–70. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2018.04.009. PMID 29626650.

- ^ Gil-Martins E, Barbosa DJ, Borges F, Remião F, Silva R (June 2025). "Toxicodynamic insights of 2C and NBOMe drugs - Is there abuse potential?". Toxicol Rep. 14: 101890. doi:10.1016/j.toxrep.2025.101890. PMC 11762925. PMID 39867514.

- ^ Kim YJ, Ma SX, Hur KH, Lee Y, Ko YH, Lee BR, et al. (April 2021). "New designer phenethylamines 2C-C and 2C-P have abuse potential and induce neurotoxicity in rodents". Arch Toxicol. 95 (4): 1413–1429. doi:10.1007/s00204-021-02980-x. PMID 33515270.

- ^ Custodio RJ, Sayson LV, Botanas CJ, Abiero A, You KY, Kim M, et al. (November 2020). "25B-NBOMe, a novel N-2-methoxybenzyl-phenethylamine (NBOMe) derivative, may induce rewarding and reinforcing effects via a dopaminergic mechanism: Evidence of abuse potential". Addict Biol. 25 (6): e12850. doi:10.1111/adb.12850. PMID 31749223.

- ^ Seo JY, Hur KH, Ko YH, Kim K, Lee BR, Kim YJ, et al. (October 2019). "A novel designer drug, 25N-NBOMe, exhibits abuse potential via the dopaminergic system in rodents". Brain Res Bull. 152: 19–26. doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2019.07.002. PMID 31279579.

- ^ Jo C, Joo H, Youn DH, Kim JM, Hong YK, Lim NY, et al. (November 2022). "Rewarding and Reinforcing Effects of 25H-NBOMe in Rodents". Brain Sci. 12 (11): 1490. doi:10.3390/brainsci12111490. PMC 9688077. PMID 36358416.

- ^ Lee JG, Hur KH, Hwang SB, Lee S, Lee SY, Jang CG (August 2023). "Designer Drug, 25D-NBOMe, Has Reinforcing and Rewarding Effects through Change of a Dopaminergic Neurochemical System". ACS Chem Neurosci. 14 (15): 2658–2666. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.3c00196. PMID 37463338.

- ^ Kim YJ, Kook WA, Ma SX, Lee BR, Ko YH, Kim SK, et al. (April 2024). "The novel psychoactive substance 25E-NBOMe induces reward-related behaviors via dopamine D1 receptor signaling in male rodents". Arch Pharm Res. 47 (4): 360–376. doi:10.1007/s12272-024-01491-4. PMID 38551761.

- ^ Fantegrossi WE, Murnane KS, Reissig CJ (January 2008). "The behavioral pharmacology of hallucinogens". Biochem Pharmacol. 75 (1): 17–33. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2007.07.018. PMC 2247373. PMID 17977517.

Despite the reasonably constant recreational use of hallucinogens since at least the early 1970s [44], the reinforcing effects of hallucinogens have not been widely investigated in laboratory animals. Indeed, one of the earliest studies on the reinforcing effects of drugs using the intravenous self-administration procedure in rhesus monkeys found that no animal initiated self-injection of mescaline either spontaneously or after one month of programmed administration [45]. Likewise, the phenethylamine hallucinogen 2,5-dimethoxy-4-methylamphetamine (DOM) was not effective in maintaining self-administration in rhesus monkeys [46]. Nevertheless, the hallucinogen-like phenethylamine 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) has been shown to act as a reinforcer in intravenous self-administration paradigms in baboons [47], rhesus monkeys [48 – 50], rats [51] and mice [52].

- ^ Canal CE, Murnane KS (January 2017). "The serotonin 5-HT2C receptor and the non-addictive nature of classic hallucinogens". J Psychopharmacol. 31 (1): 127–143. doi:10.1177/0269881116677104. PMC 5445387. PMID 27903793.

One of the earliest studies on the reinforcing effects of drugs using the intravenous self-administration procedure in rhesus monkeys found that no animal initiated self-injection of mescaline either spontaneously or after one month of programmed administration, [...] (Deneau et al., 1969). The lack of mescaline self-administration stood in contrast to positive findings of self-administration of morphine, codeine, cocaine, amphetamine, pentobarbital, ethanol, and caffeine. A subsequent study with rhesus monkeys using 2,5-dimethoxy-4-methylamphetamine (DOM; Yanagita, 1986) provided similar results as the mescaline study. These findings have withstood the test of time, as the primary literature is virtually devoid of any accounts of self-administration of [classical hallucinogens (CH)], suggesting that there are very limited conditions under which laboratory animals voluntarily consume CH.

- ^ Yanagita T (June 1986). "Intravenous self-administration of (-)-cathinone and 2-amino-1-(2,5-dimethoxy-4-methyl)phenylpropane in rhesus monkeys". Drug Alcohol Depend. 17 (2–3): 135–141. doi:10.1016/0376-8716(86)90004-9. PMID 3743404.

- ^ Maguire DR (October 2024). "Evaluation of potential punishing effects of 2,5-dimethoxy-4-methylamphetamine (DOM) in rhesus monkeys responding under a choice procedure". Behav Pharmacol. 35 (7): 378–385. doi:10.1097/FBP.0000000000000787. PMID 39052019.

- ^ a b "Erowid DOC Vault: Dosage". Archived from the original on 2 May 2008. Retrieved 22 April 2008.

- ^ a b "Erowid Online Books: "PiHKAL" - #64 DOC". Archived from the original on 3 August 2018. Retrieved 17 November 2005.

- ^ Bucks J (25 April 2013). ""Moment of madness": rare drug implicated in student death". The Saint. Archived from the original on 28 April 2013. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ^ Barnett RY, Baker DD, Kelly NE, McGuire CE, Fassette TC, Gorniak JM (October 2014). "A fatal intoxication of 2,5-dimethoxy-4-chloroamphetamine: a case report". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 38 (8): 589–91. doi:10.1093/jat/bku087. PMID 25217551.

- ^ Baselt RC (2014). Disposition of toxic drugs and chemicals in man. Seal Beach, California: Biomedical Publications. p. 2173. ISBN 978-0-9626523-9-4.

- ^ "mg1207" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-17. Retrieved 2013-08-13.

- ^ "Schedule I". Controlled Drugs and Substances Act. Canadian Legal Information Institute. 2022-03-31. Archived from the original on 2022-03-31. Retrieved 2022-03-31.

- ^ "Controlled Drugs and Substances Act". Definitions and interpretations. Canadian Legal Information Institute. Archived from the original on 2013-11-10. Retrieved 2022-03-31.

- ^ "Backgrounder: The Safe Streets and Communities Act Four Components Coming Into Force". Canadian Department of Justice. Archived from the original on 2012-10-18.

- ^ a b c d e f "Erowid DOC Vault: Legal Status". Archived from the original on 1 May 2008. Retrieved 22 April 2008.

- ^ "关于印发《非药用类麻醉药品和精神药品列管办法》的通知" (in Chinese). China Food and Drug Administration. 27 September 2015. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- ^ "Läkemedelsverkets föreskrifter - LVFS och HSLF-FS | Läkemedelsverket" (PDF).

- ^ "Förordning om ändring i förordningen (1999:58) om förbud mot vissa hälsofarliga varor" (PDF) (in Swedish). 27 May 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 September 2018.

- ^ "PART 1308 - Section 1308.11 Schedule I". www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov. Archived from the original on 27 August 2009. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ^ "DEA Resources, Microgram, October 2007" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-17. Retrieved 2012-10-03.

- ^ "Schedules of Controlled Substances: Placement of 2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine (DOI) and 2,5-dimethoxy-4-chloroamphetamine (DOC) in Schedule I". www.regulations.gov.

- ^ "The 2017 Florida Statutes - Title XLVI - CRIMES - Chapter 893 - DRUG ABUSE PREVENTION AND CONTROL". leg.state.fl.us. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ^ "December 2019 – WHO: World Health Organization recommends 12 NPS for scheduling".