Buddha contemplation

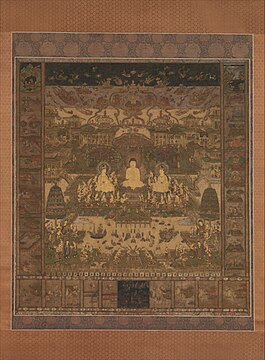

Buddha contemplation (Chinese: guānfo 觀佛), is a central Buddhist meditation practice in East Asian Buddhism, especially popular in Pure Land Buddhism, but also found in other traditions such as Tiantai and Huayan. This practice involves the visualization and contemplation of a mental image of a Buddha and the attributes of their Pure Land, aiming to develop faith, devotion, and a deep connection to the Buddha's spiritual qualities.[1] As such, Buddha contemplation is a Mahayana type of "buddha mindfulness" (buddhānusmṛti) meditation which focuses on imagination or visualization. The most popular Buddha used in this practice is Amitābha, but other figures are also used, like Guanyin, Cundi, and Samantabhadra.

The practice of Buddha contemplation is taught in various Mahayana sutras called Contemplation Sutras (Chinese: 觀經, Guān jīng, sometimes also translated as Visualization Sutras), which teaches contemplative practices based on fantastic visual images of Buddhas, bodhisattvas and their buddhafields.[2][1] These works mostly survive in Chinese translations dating from about the sixth century CE.[2][1]

Overview

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Pure Land Buddhism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Mahāyāna Buddhism |

|---|

|

In Pure Land Buddhism, guānfo is primarily associated with the meditation on Amitābha Buddha and his Western Pure Land, Sukhāvatī, a realm of bliss and enlightenment. Practitioners visualize Amitābha surrounded by serene landscapes and the Pure Land's inhabitants, such as bodhisattvas and celestial beings. They may also practice any of the thirteen visualizations taught in the Contemplation Sūtra (觀經, Guān jīng), which includes visualization of the sun, of the ponds and trees of the Pure land and of the bodhisattvas Guanyin and Dàshìzhì.[1] The visualization meditation of guanfo is often accompanied by recitation of the Buddha’s name (nianfo in Chinese). It is believed that through such practices, practitioners can purify their minds, and attain birth in the pure land.

The practice of Buddha Contemplation is taught in several texts which teach this method known as Contemplation Sutras. A main feature of these Contemplation Sutras is the visual imagery used, though only some include actual meditation practices which use visualization. There is no consensus on a Sanskrit basis for the term "guan" (觀, which can mean contemplation or visualization). While the sutras present themselves as translations no Indic originals have been found. Scholars disagree on their origin, possibly Central Asia or China.[3]

Buddha contemplation is similar to and historically precedes the Vajrayana practice of Deity yoga. Some scholars see Buddha contemplation sources as being precursors to deity yoga.[4] However, unlike the tantric deity yoga, Buddha contemplation does not require esoteric initiation (abhiseka), make use of mudras, mandalas or special mantras.

Sources

[edit]The Contemplation Sutras

[edit]There are various Mahayana sutras associated with the term guan, though generally six major texts as seen as the central "Contemplation sutras" (Chinese: 觀經, Guān jīng) as listed by Alexander Coburn Soper (1959).[5][1]

- Sutra on the Sea of Samādhi Attained through Contemplation of the Buddha (Guan Fo Sanmei Hai Jing, 觀佛三昧海經, T.643), commonly known as Samādhi Sea Sutra. According to Yamabe, this is the oldest of the bunch.[6] This was translated by Buddhabhadra (359-429 CE) .

- Sutra on the Contemplation of the Buddha of Immeasurable Life (Guan Wuliangshoufo Jing, 佛说观无量寿佛经 T.365). Commonly known as the Contemplation Sutra, it was translated by Kālayaśas (fl. 424-442).

- Sutra on the Contemplation CE. the Two Bodhisattvas Bhaiṣajyarāja and Bhaiṣajyasamudgata (Guan Yaowang Yaoshang Erpusa Jing), commonly known as Bhaiṣajyarāja Contemplation Sutra

- Sutra on the Contemplation of Maitreya Bodhisattva's Ascent to Rebirth in Tusita Heaven (Guan Mile Pusa Shangsheng Doushuaitian Jing), commonly known as Maitreya Contemplation Sutra

- Sutra on the Contemplation of the Cultivation Methods of the Bodhisattva Samantabhadra (Guan Puxian Pusa Xingfa Jing), commonly known as Samantabhadra Contemplation Sutra

- Sutra on the Contemplation of the Bodhisattva Ākāśagarbha (Guan Xukongzang Pusa Jing), commonly known as Ākāśagarbha Contemplation Sutra.

Other sources

[edit]Nobuyoshi Yamabe notes that the following texts also have a similarity to the visualization sutras, some of these are part of the so called "Meditation Sutra" category (Ch: chanjing):[7]

- A Manual on the Secret Essence of Meditation (Chan Miyaofa jing)

- The Secret Essential Methods to Cure the Diseases Caused by Meditation (Zhi chanbing miyao fa)

- The Essence of the Meditation Manual consisting of Five Gates (Wumen chanjing yaoyong fa)

- The Yogalehrbuch (Yoga textbook), an anonymous meditation manual in Sanskrit found at Kizil Caves. Yamabe notes that the visualization practices here are similar to the Sea of Samadhi sutra.

Furthermore, other sutras briefly discuss the visionary contemplation of Buddhas, like the Pratyutpanna Samādhi Sūtra, whose full title is Pratyutpannabuddha Saṃmukhāvasthita Samādhi Sūtra ("Sūtra on the Samādhi for Encountering Face-to-Face the Buddhas of the Present").[8]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Quinter, David (2021-09-29), "Visualization/Contemplation Sutras (Guan Jing)", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion, ISBN 978-0-19-934037-8, retrieved 2024-12-12

- ^ a b Yamabe, Nobuyoshi. The significance of the "Yogalehrbuch" for the Investigation into the Origin of Chinese Meditation Texts, 1999, The institute of Buddhist Culture, Kyushu Ryukoku Junior College

- ^ Quinter, David; Visualization/Contemplation Sutras, Oxford Bibliographies, Last reviewed: 08 MAY 2017. Last modified: 26 FEBRUARY 2013,http://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780195393521/obo-9780195393521-0137.xml#obo-9780195393521-0137-bibItem-0014

- ^ Samuel, Geoffrey (2010). The Origins of Yoga and Tantra. Indic Religions to the Thirteenth Century, pp. 219-222. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Soper, Alexander Coburn. Literary Evidence for Early Buddhist Art in China. Artibus Asiae Supplementum 19. Ascona, Switzerland: Artibus Asiae, 1959.

- ^ Yamabe, Nobuyoshi. The significance of the "Yogalehrbuch" for the Investigation into the Origin of Chinese Meditation Texts, Buddhist Culture, The institute of Buddhist Culture, Kyushu Ryukoku Junior College

- ^ Yamabe, Nobuyoshi. The significance of the "Yogalehrbuch" for the Investigation into the Origin of Chinese Meditation Texts, Buddhist Culture, The institute of Buddhist Culture, Kyushu Ryukoku Junior College

- ^ Buswell, Robert Jr; Lopez, Donald S. Jr., eds. (2013). Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 674. ISBN 9780691157863.

Other sources

[edit]- Ponampon, Phra Kiattisak. "Dunhuang Manuscript S.2585: a Textual and Interdisciplinary Study on Early Medieval Chinese Buddhist Meditative Techniques and Visionary Experiences." MPhil Diss., University of Cambridge, 2019.

- Soper, Alexander Coburn. Literary Evidence for Early Buddhist Art in China. Artibus Asiae Supplementum 19. Ascona, Switzerland: Artibus Asiae, 1959.

- Fujita Kōtatsu (藤田 宏達). “The Textual Origins of the Kuan Wu-Liang-Shou Ching: A Canonical Scripture of Pure Land Buddhism.” Translated by Kenneth K. Tanaka. In Chinese Buddhist Apocrypha. Edited by Robert E. Buswell Jr., 149–173. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1990.

- Yamabe, Nobuyoshi. “The Sūtra on the Ocean-Like Samādhi of the Visualization of the Buddha: The Interfusion of the Chinese and Indian Cultures in Central Asia as Reflected in a Fifth Century Apocryphal Sūtra.” PhD diss., Yale University, 1999.

- Yamabe, Nobuyoshi. The significance of the "Yogalehrbuch" for the Investigation into the Origin of Chinese Meditation Texts, Buddhist Culture, The institute of Buddhist Culture, Kyushu Ryukoku Junior College