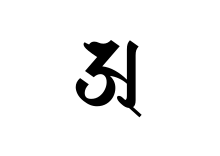

Trikaya

The Trikāya (Sanskrit: त्रिकाय, lit. "three bodies"; Chinese: 三身; pinyin: sānshēn; Japanese pronunciation: sanjin, sanshin; Korean pronunciation: samsin; Vietnamese: tam thân, Tibetan: སྐུ་གསུམ, Wylie: sku gsum) is a fundamental Mahayana Buddhist doctrine that explains the multidimensional nature of Buddhahood. As such, the Trikāya is the basic theory of Mahayana Buddhist Buddhology (i.e. the theology of Buddhahood).[1]

This concept posits that a Buddha has three distinct "bodies", aspects, or ways of being, each representing a different facet of enlightenment.[2] They are the Dharmakāya (Dharma body, the ultimate reality, the true nature of all things), the Sambhogakāya (the body of self-enjoyment, a blissful divine body with infinite forms and powers) and the Nirmāṇakāya (manifestation body, the body which appears in the everyday world and presents the semblance of a human body).

The Trikāya doctrine explains how a Buddha can simultaneously exist in multiple realms and embody a spectrum of qualities and forms, while also seeming to appear in the world with a human body that gets old and dies (though this is merely an appearance). The doctrine's interpretations may vary across different Buddhist traditions, some theories contain extra "bodies", making it a "four body" theory and so on. However, the basic Trikāya theory remains a cornerstone of Mahayana and Vajrayana teachings, providing a comprehensive perspective on the nature of Buddhahood, Buddhist deities and the Buddhist cosmos.

Overview of the concept

[edit]

The Trikāya doctrine sees Buddhahood as composed of three bodies, components or collection of elements (kāya): the Dharma body (the ultimate aspect of Buddhahood), the body of self-enjoyment (a divine and magical aspect) and the manifestation body (a more human and earthly aspect).[6]

Dharmakāya

[edit]The Dharmakāya, "Dharma body," (sometimes also called svabhāvikakāya - the intrinsic body) is often described through Buddhist philosophical concepts that describe the Buddhist view of ultimate reality like emptiness, Buddha nature, Dharmata, Suchness (Tathātā), Dharmadhatu, Prajñaparamita, and Paramartha.[7][8][2]

The Dharma-body is usually associated with Buddha names like Mahavairocana, Vajradhara and Samantabhadra.[7] The Dharma body embodies the true nature of Buddhahood itself. It is generally understood as impersonal, without concept, words or thought. It is the true nature of all things (dharmas) and the true nature of all beings, equivalent to the Mahayana concept of emptiness (śūnyatā), the lack of inherent essence in all things.[9] As such, it may be compared to the Vedantic concept of Nirguna Brahman, another Indic concept of an ultimate reality without any form or qualities.

The Dharmakāya is also associated with the "body of the teachings", that is to say, the Buddhadharma, the teachings of the Buddha, and by association, with the nature of reality itself (i.e. the Dharma and the nature of the dharmas - all phenomena), which the teachings point to and are in accord with.[10]

The Dharma-body is often described in apophatic terms (especially in Madhyamaka sources), as formless, thought-less and beyond all concepts, language and ideas - including any idea of existence (bhava) or non-existence (abhava), or eternalism (śāśvata-dṛṣṭi) and annihilation (ucchedavāda).[11] For example, according to Paul Williams, the Hymn to the Ultimate (Paramārthastava) by Nagarjuna describes the Buddha in negative terms as follows:

The Buddha is neither nonbeing nor being, neither annihilation nor permanence, not noneternal, not eternal. He falls into no category of duality. He has no colour, no size, no spatial location and so on. He cannot therefore be praised. And Nagarjuna ends with another of his gentle jokes: ‘I have praised the Well-gone [Sugata – an epithet of the Buddha] who is neither gone nor come, and who is devoid of any going’.[11]

In Indian Yogācāra school sources, the Dharmakāya is sometimes described in more positive ways. According to Williams, Yogācāra sees the Dharmakāya as the support or basis of all dharmas, and as being a self-contained nature (svabhāva) which lacks anything contingent or adventitious.[9] It is thus "the intrinsic nature of the Buddhas, the ultimate, the purified Thusness or Suchness " and "true nature of things taken as a body", a non-dual, pure and immaculate wisdom.[9]

The Yogācāra also sees the Dharmabody as equivalent to the dharmadhātu (the totality of the cosmos) in its ultimate sense, in other words "the intrinsic body of the Buddha is the intrinsic or fundamental dimension of the cosmos".[12] According to Yogācāra, on this ultimate level, there is no distinction between different Buddhas, there is only the same non-dual reality beyond all concepts including singularity and multiplicity.[12]

Saṃbhogakāya

[edit]The Saṃbhogakāya (Co-enjoyment, or Bliss body) refers to the divine magical bodies of the Buddhas which manifest in many different skillful ways at many different times and places for the benefit of all living beings.[2][12] The term is usually associated with more supramundane, cosmic or otherworldly Buddhas like Amitabha.[7] While this aspect of Buddhahood does appear to have a kind of form, it is a form that transcends the three worlds and all material existence.[12] This body is the object of popular Buddhist devotion in Mahayana Buddhism, it is the Buddha as an omniscient transcendent being with immense powers, animated only by universal compassion for all living things.[13]

Some Yogācāra sources, like Xuanzang’s Chengweishilun, describe the enjoyment body as having two aspects: a private aspect which is experienced by Buddhas themselves and an aspect manifested for the sake of others' benefit.[13]

The co-enjoyment aspect is associated with the blissful reward of Buddhahood. It is considered a skillful manifestation that arises as a result of fulfilling vows and commitments on the spiritual journey. The bliss body embodies the idea of reaping the benefits or rewards of spiritual practice and dwelling in sublime states of realization. It is also associated with divine pure lands (buddha-fields) which are extensions of the Saṃbhogakāya Buddhas, as well as with all the numerous emanations which are manifested by the Saṃbhogakāya as a skillful means to guide different types of beings.

Nirmāṇakāya

[edit]

The Nirmāṇakāya, the body of transformation, manifestation or appearance [2] (also called rūpa-kaya, form body), refers to a Buddha's human-like manifestations in imperfect worlds like ours, which appear for limited periods of time and seemingly die in paranirvana. It is usually associated with "historical" Buddha figures, like Shakyamuni Buddha.[2] The third body, the Nirmanakaya, is referred to as the "Transformation body." Manifestation bodies allow Buddhas to interact with and teach sentient beings in a more direct and human manner. They typically appear as male monastics in most Mahayana sutras, though later they encompassed all sorts of bodies. This earthly embodiment serves as a bridge between the divine and the human realm. It makes the teachings and compassion of a Buddha accessible to beings of impure realms who seek guidance from an awakened being. However, even this more human-like Buddha is not just a normal human body. A Nirmāṇakāya only appears human, in reality it is just a phantom like magic body, a mere docetic appearance, which can manifest numerous magical powers.[14]

The Buddha's physical body also has a very unique appearance, made up of the 32 major marks of great man. These characteristics include such unusual features as dharma wheels on the soles of his feet, glowing golden skin, unnaturally long tongue and arms which extend to his knees, and unique facial features like the uṣṇīṣa (a fleshly dome on top of his head) and ūrṇākośa (circle of hair between his eyebrows).[15]

Nirmāṇakāyas often appear in a world to turn the wheel of Dharma (i.e. teach Buddhism) and to display the basic acts of a Buddha (such as miraculous birth, renunciation, enlightenment under a bodhi tree, etc) and they also may found a Sangha which maintains the teaching even after the Nirmāṇakāya has manifested nirvana.[13] However, this is not always the case, and a Nirmāṇakāya may perform unsual acts, like teaching non-Buddhist teachings or appearing as an animal (as in the Jatakas) for example, if this is the skillful means that is required to teach certain beings.[13]

Historically, the form body of the Buddha was also associated with specific stupas, where the relics of the historical Buddha's body were believed to have been located.[16]

Indian Buddhist history

[edit]The concept of two Buddha bodies - physical and Dharma body, appears in non-Mahayana Buddhist sources, like the works of the Sarvastivada school. In this non-Mahayana context, Dharmakāya referred to the "body of the teachings", the teachings of the Buddha in the Tripitaka and their final intent, the ultimate nature of the dharmas.[10] It could also refer to the set of all dharmas (phenomena, attributes, characteristics) that was possessed by a Buddha, i.e. "those factors (dharmas) the possession of which serves to distinguish a Buddha from one who is not a Buddha.".[17] For the Sarvastivada school, this "body of dharmas" (Buddha's teachings and buddha-qualities) was the highest and true refuge, which does not pass away like the Buddha's physical body.[10]

Early Mahayana sutras like the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā (c. 1st century BCE) also mostly follow this basic model of two bodies: the body of Dharma and the form body (rūpa-kaya).[17] According to the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā, only fools think of the Buddha as being his physical body, since: "a Tathāgata is not to be seen through his physical body; Tathāgata have the Dharma as their body."[17] Some scholars like Yuichi Kajiyama have argued that this sutra's critique of people who think the Buddha is to be found in his physical body is a criticism of stupa worship, and that the Perfection of Wisdom sutra was attempting to replace stupa worship with worship of the Perfection of Wisdom itself.[18] Some scholars think that the Mahayana idea of the Dharma body evolved over time to signify the ultimate reality itself, the Dharmata (Dharma-ness), the emptiness of all dharmas, and the Buddha's wisdom (prajñaparamita) which knows that reality.[18]

Later Mahayana sources introduced the Sambhogakāya, which conceptually fits between the Nirmāṇakāya (the physical manifestation of enlightenment) and the Dharmakaya. The mature three bodies theory developed in the Yogācāra school (in around the 4th century) and can be seen in sources like the Mahāyāna-sūtrālamkāra (and its commentary) as well as Asanga's Mahāyānasaṃgraha.[19][9]

Interpretation in Buddhist traditions

[edit]Various Buddhist traditions have different ideas about what the three bodies are.[web 1][web 2]

Chinese Buddhism

[edit]The Three Bodies of the Buddha consists of:[20][21]

- The Nirmaṇakāya, which is a physical/manifest body of a Buddha. An example would be Gautama Buddha's body.

- The Sambhogakāya, which is the reward/enjoyment body, whereby a bodhisattva completes his vows and becomes a Buddha. Amitābha, Vajrasattva and Manjushri are examples of Buddhas with the Sambhogakaya body.

- The Dharmakāya, which is the embodiment of the truth itself, and it is commonly seen as transcending the forms of physical and spiritual bodies. Vairocana Buddha is often depicted as the Dharmakāya in the Chinese Esoteric Buddhist and Huayan traditions.

As with earlier Buddhist thought, all three forms of the Buddha teach the same Dharma, but take on different forms to expound the truth.

According to Schloegl, in the Zhenzhou Linji Huizhao Chansi Yulu (which is a Chan Buddhist compilation), the Three Bodies of the Buddha are not taken as absolute. They would be "mental configurations" that "are merely names or props" and would only perform a role of light and shadow of the mind.[22][note 1]

The Zhenzhou Linji Huizhao Chansi Yulu advises:

Do you wish to be not different from the Buddhas and patriarchs? Then just do not look for anything outside. The pure light of your own heart [i.e., 心, mind] at this instant is the Dharmakaya Buddha in your own house. The non-differentiating light of your heart at this instant is the Sambhogakaya Buddha in your own house. The non-discriminating light of your own heart at this instant is the Nirmanakaya Buddha in your own house. This trinity of the Buddha's body is none other than here before your eyes, listening to my expounding the Dharma.[24]

Japanese Buddhism

[edit]In Tendai and Shingon of Japan, they are known as the Three Mysteries (三密, sanmitsu).

Tibetan Buddhism

[edit]According to W.Y. Evans-Wentz, the trikaya represents the esoteric trinity (three bodies) of the Northern School of Buddhism (Mahayana). It consists of:

- Dharmakaya, the essential divine body of truth

- Sambhogakaya, the reflected divine body of glory

- Nirmanakaya, the practical divine body of incarnation

It is through these three divine bodies that One-Wisdom, the One-Mind manifests itself.[25][page needed] [26][page needed]

Three Vajras

[edit]The Three Vajras, namely "body, speech and mind", are a formulation within Vajrayana Buddhism and Bon that hold the full experience of the śūnyatā "emptiness" of Buddha-nature, void of all qualities (Wylie: yon tan) and marks[27] (Wylie: mtshan dpe) and establish a sound experiential key upon the continuum of the path to enlightenment. The Three Vajras correspond to the trikaya and therefore also have correspondences to the Three Roots and other refuge formulas of Tibetan Buddhism. The Three Vajras are viewed in twilight language as a form of the Three Jewels, which imply purity of action, speech and thought.

The Three Vajras are often mentioned in Vajrayana discourse, particularly in relation to samaya, the vows undertaken between a practitioner and their guru during empowerment. The term is also used during Anuttarayoga Tantra practice.

The Three Vajras are often employed in tantric sādhanā at various stages during the visualization of the generation stage, refuge tree, guru yoga and iṣṭadevatā processes. The concept of the Three Vajras serves in the twilight language to convey polysemic meanings,[citation needed] aiding the practitioner to conflate and unify the mindstream of the iṣṭadevatā, the guru and the sādhaka in order for the practitioner to experience their own Buddha-nature.

Speaking for the Nyingma tradition, Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche perceives an identity and relationship between Buddha-nature, dharmadhatu, dharmakāya, rigpa and the Three Vajras:

Dharmadhātu is adorned with Dharmakāya, which is endowed with Dharmadhātu Wisdom. This is a brief but very profound statement, because "Dharmadhātu" also refers to Sugatagarbha or Buddha-Nature. Buddha- Nature is all-encompassing... This Buddha-Nature is present just as the shining sun is present in the sky. It is indivisible from the Three Vajras [i.e. the Buddha's Body, Speech and Mind] of the awakened state, which do not perish or change.[28]

Robert Beer (2003: p. 186) states:

The trinity of body, speech, and mind are known as the three gates, three receptacles or three vajras, and correspond to the western religious concept of righteous thought (mind), word (speech), and deed (body). The three vajras also correspond to the three kayas, with the aspect of body located at the crown (nirmanakaya), the aspect of speech at the throat (sambhogakaya), and the aspect of mind at the heart (dharmakaya)."[29]

The bīja corresponding to the Three Vajras are: a white om (enlightened body), a red ah (enlightened speech) and a blue hum (enlightened mind).[30]

Simmer-Brown (2001: p. 334) asserts that:

When informed by tantric views of embodiment, the physical body is understood as a sacred maṇḍala (Wylie: lus kyi dkyil).[31]

This explicates the semiotic rationale for the nomenclature of the somatic discipline called trul khor.

The triple continua of body-voice-mind are intimately related to the Dzogchen doctrine of "sound, light and rays" (Wylie: sgra 'od zer gsum) as a passage of the rgyud bu chung bcu gnyis kyi don bstan pa ('The Teaching on the Meaning of the Twelve Child Tantras') rendered into English by Rossi (1999: p. 65) states (Tibetan provided for probity):

|

|

Barron et al. (1994, 2002: p. 159), renders from Tibetan into English, a terma "pure vision" (Wylie: dag snang) of Sri Singha by Dudjom Lingpa that describes the Dzogchen state of 'formal meditative equipoise' (Tibetan: nyam-par zhag-pa) which is the indivisible fulfillment of vipaśyanā and śamatha, Sri Singha states:

Just as water, which exists in a naturally free-flowing state, freezes into ice under the influence of a cold wind, so the ground of being exists in a naturally free state, with the entire spectrum of samsara established solely by the influence of perceiving in terms of identity.

Understanding this fundamental nature, you give up the three kinds of physical activity--good, bad, and neutral--and sit like a corpse in a charnal ground, with nothing needing to be done. You likewise give up the three kinds of verbal activity, remaining like a mute, as well as the three kinds of mental activity, resting without contrivance like the autumn sky free of the three polluting conditions.[33]

Buddha-bodies

[edit]Vajrayana sometimes refers to a fourth body called the svābhāvikakāya (Tibetan: ངོ་བོ་ཉིད་ཀྱི་སྐུ, Wylie: ngo bo nyid kyi sku) "essential body",[web 3][34][web 4] and to a fifth body, called the mahāsūkhakāya (Wylie: bde ba chen po'i sku, "great bliss body").[35] The svābhāvikakāya is simply the unity or non-separateness of the three kayas.[web 5] The term is also known in Gelug teachings, where it is one of the assumed two aspects of the dharmakāya: svābhāvikakāya "essence body" and jñānakāya "body of wisdom".[36]

Haribhadra claims that the Abhisamayalankara describes Buddhahood through four kāyas in chapter 8: svābhāvikakāya, [jñāna]dharmakāya, sambhogakāya and nirmāṇakāya.[37]

In dzogchen teachings, "dharmakaya" means the buddha-nature's absence of self-nature, that is, its emptiness of a conceptualizable essence, its cognizance or clarity is the sambhogakaya, and the fact that its capacity is 'suffused with self-existing awareness' is the nirmanakaya.[38]

The interpretation in Mahamudra is similar: When the mahamudra practices come to fruition, one sees that the mind and all phenomena are fundamentally empty of any identity; this emptiness is called dharmakāya. One perceives that the essence of mind is empty, but that it also has a potentiality that takes the form of luminosity.[clarification needed] In Mahamudra thought, Sambhogakāya is understood to be this luminosity. Nirmanakāya is understood to be the powerful force with which the potentiality affects living beings.[39]

In the view of Anuyoga, the Mind Stream (Sanskrit: citta santana) is the 'continuity' (Sanskrit: santana; Wylie: rgyud) that links the Trikaya.[web 6] The Trikāya, as a triune, is symbolised by the Gankyil.

Dakinis

[edit]A ḍākinī (Tibetan: མཁའ་འགྲོ་[མ་], Wylie: mkha' 'gro [ma] khandro[ma]) is a tantric deity described as a female embodiment of enlightened energy. The Sanskrit term is likely related to the term for drumming, while the Tibetan term means "sky goer" and may have originated in the Sanskrit khecara, a term from the Cakrasaṃvara Tantra.[40]

Ḍākinīs can also be classified according to the trikāya theory. The dharmakāya ḍākinī, which is Samantabhadrī, represents the dharmadhatu where all phenomena appear. The sambhogakāya ḍākinī are the yidams used as meditational deities for tantric practice. The nirmanakaya ḍākinīs are human women born with special potentialities; these are realized yogini, the consorts of the gurus, or even all women in general as they may be classified into the families of the Five Tathagatas.[web 7]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Lin-ji yu-lu: "The scholars of the Sutras and Treatises take the Three Bodies as absolute. As I see it, this is not so. These Three Bodies are merely names, or props. An old master said: "The (Buddha's) Bodies are set up with reference to meaning; the (Buddha) Fields are distinguished with reference to substance." However, understood clearly, the Dharma Nature Bodies and the Dharma Nature Fields are only mental configurations."[23]

References

[edit]- ^ de la Vallée Poussin, Louis. (1906). "XXXI. Studies in Buddhist Dogma. The Three Bodies of a Buddha (Trikāya)." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland, 38(4), 943–977. doi:10.1017/S0035869X0003522X

- ^ a b c d e Snelling 1987, p. 100.

- ^ Robert E. Buswell and Donald S. Lopez (2014). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, pp. 1, 24. Published by Princeton University Press

- ^ "The Bija/Seed Syllable A in Siddham, Tibetan, Lantsa scripts - meaning and use in Buddhism". www.visiblemantra.org. Archived from the original on 2021-12-23. Retrieved 2022-07-12.

- ^ Strand, Clark (2011-05-12). "Green Koans 45: The Perfection of Wisdom in One Letter". Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. Archived from the original on 2020-11-24. Retrieved 2022-07-12.

- ^ Williams 2009, p. 174.

- ^ a b c Griffin 2018, p. 278.

- ^ Williams 2009, p. 178-179.

- ^ a b c d Williams 2009, p. 179.

- ^ a b c Williams 2009, p. 175.

- ^ a b Williams 2009, p. 178.

- ^ a b c d Williams 2009, p. 180.

- ^ a b c d Williams 2009, p. 181.

- ^ Williams 2009, p. 173, 181.

- ^ Mattice, S.A. (2021). Exploring the Heart Sutra. Lexington Books. p. 128. ISBN 978-1-4985-9941-2. Retrieved 2023-08-23.

- ^ Williams 2009, p. 177.

- ^ a b c Williams 2009, p. 176.

- ^ a b Williams 2009, p. 177-78.

- ^ Snelling 1987, p. 126.

- ^ Xing, Guang (2004-11-10). The Concept of the Buddha: Its Evolution from Early Buddhism to the Trikaya Theory. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203413104. ISBN 978-0-203-41310-4.

- ^ Habito, Ruben L. F. (1986). "The Trikāya Doctrine in Buddhism". Buddhist-Christian Studies. 6: 53–62. doi:10.2307/1390131. ISSN 0882-0945. JSTOR 1390131.

- ^ Schloegl 1976, p. 19.

- ^ Schloegl 1976, p. 21.

- ^ Schloegl 1976, p. 18.

- ^ W.Y. Evans-Wentz, Tibetan Yoga and Secret Doctrines, Oxford University Press, London: Humphrey Milford, 1935; pp 39-40, 46

- ^ W.Y. Evans-Wentz, The Tibetan Book of the Dead, Oxford University Press, London: Humphrey Milford, 1927; pp 10-15

- ^ '32 major marks' (Sanskrit: dvātriṃśanmahāpuruṣalakṣaṇa), and the '80 minor marks' (Sanskrit: aśītyanuvyañjana) of a superior being, refer: Physical characteristics of the Buddha.

- ^ As It Is, Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche, Rangjung Yeshe Books, Hong Kong, 1999, p. 32

- ^ Beer, Robert (2003). The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols. Serindia Publications. ISBN 1-932476-03-2 Source: [1] (accessed: December 7, 2007)

- ^ Rinpoche, Pabongka (1997). Liberation in the Palm of Your Hand: A Concise Discourse on the Path to Enlightenment. Wisdom Books. p. 196.

- ^ Simmer-Brown, Judith (2001). Dakini's Warm Breath: the Feminine Principle in Tibetan Buddhism. Boston, USA: Shambhala. ISBN 1-57062-720-7 (alk. paper). p.334

- ^ a b Rossi, Donatella (1999). The philosophical view of the great perfection in the Tibetan Bon religion. Ithaca, NY: Snow Lion Publications. p. 65. ISBN 1-55939-129-4.

- ^ Lingpa, Dudjom; Tulku, Chagdud; Norbu, Padma Drimed; Barron, Richard (Lama Chökyi Nyima, translator); Fairclough, Susanne (translator) (1994, 2002 revised). Buddhahood without meditation: a visionary account known as 'Refining one's perception' (Nang-jang) (English; Tibetan: ran bźin rdzogs pa chen po'i ranźal mnon du byed pa'i gdams pa zab gsan sñin po). Revised Edition. Junction City, CA, USA: Padma Publishing. ISBN 1-881847-33-0, p.159

- ^ In the book Embodiment of Buddhahood Chapter 4 the subject is: Embodiment of Buddhahood in its Own Realization: Yogacara Svabhavikakaya as Projection of Praxis and Gnoseology.

- ^ Tsangnyön Heruka (1995). The life of Marpa the translator : seeing accomplishes all. Boston: Shambhala. p. 229. ISBN 978-1570620874.

- ^ Williams 2009.

- ^ Makransky, John J. (1997). Buddhahood embodied : sources of controversy in India and Tibet. Albany, NY: State Univ. of New York Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-0791434314.

- ^ Reginald Ray, Secret of the Vajra World. Shambhala 2001, page 315.

- ^ Reginald Ray, Secret of the Vajra World. Shambhala 2001, pages 284-285.

- ^ Buswell, Robert Jr; Lopez, Donald S. Jr., eds. (2013). Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691157863.

Sources

[edit]- Printed sources

- Griffin, David Ray (2018), Reenchantment without Supernaturalism: A Process Philosophy of Religion, Cornell University Press

- Makransky, John J. (1997), Buddhahood Embodied: Sources of Controversy in India and Tibet, State University of New York Press, ISBN 0-7914-3432-X

- Schloegl, Irmgard (1976), The Zen Teaching of Rinzai (PDF), Shambhala Publications, Inc., ISBN 0-87773-087-3

- Snellgrove, David (1987). Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, Vol. 1. Boston, Massachusetts: Shambhala Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-87773-311-2.

- Snellgrove, David (1987). Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, Vol. 2. Boston, Massachusetts: Shambhala Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-87773-379-1.

- Snelling, John (1987), The Buddhist handbook. A Complete Guide to Buddhist Teaching and Practice, London: Century Paperbacks

- Walsh, Maurice (1995). The Long Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Dīgha Nikāya. Boston: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-103-3.

- Williams, Paul (2009). Mahayana Buddhism: the doctrinal foundations, 2nd ed. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-203-42847-1.

- Web sources

- ^ 佛三身觀之研究-以漢譯經論為主要研究對象 [dead link]

- ^ 佛陀的三身觀

- ^ remarks on Svabhavikakaya by khandro.net

- ^ explanation of meaning

- ^ khandro.net citing H.E. Tai Situpa

- ^ Welwood, John (2000). The Play of the Mind: Form, Emptiness, and Beyond, accessed January 13, 2007

- ^ Cf. Capriles, Elías (2003/2007). Buddhism and Dzogchen [2]', and Capriles, Elías (2006/2007). Beyond Being, Beyond Mind, Beyond History, vol. I, Beyond Being[3]

Further reading

[edit]- Radich, Michael (2007). Problems and Opportunities in the Study of the Bodies of the Buddha, New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 9 (1), 46-69

- Radich, Michael (2010). Embodiments of the Buddha in Sarvâstivāda Doctrine: With Special Reference to the Mahavibhāṣā. Annual Report of the International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology 13, 121-172

- Xing, Guang (2005). The Concept of the Buddha: Its Evolution from Early Buddhism to the Trikāya Theory. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-33344-3.