ASASSN-21qj

| Observation data Epoch J2000.0 Equinox J2000.0 | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Puppis |

| Right ascension | 08h 15m 23.300s[1] |

| Declination | −38° 59′ 23.30″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 13.48±0.034[2] |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | 25.8±3[2] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: −9.692[1] mas/yr[1] Dec.: 7.349[1] mas/yr[1] |

| Parallax (π) | 1.7631 ± 0.0112 mas[1] |

| Distance | 1,850 ± 10 ly (567 ± 4 pc) |

| Details[2] | |

| Mass | 0.94 ± 0.07[3] M☉ |

| Radius | 1.045 R☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 4.339±0.005 cgs |

| Temperature | 5,760±10 K |

| Metallicity [Fe/H] | −0.23±0.01 dex |

| Rotation | 4.43 ± 0.33 days |

| Age | 300±92 Myr |

| Other designations | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

ASASSN-21qj, also known as 2MASS J08152329-3859234, is a Sun-like main sequence star with a rotating disk of circumstellar dust and gas which are leftovers from its stellar formation around 300 million years ago. The star is located 1,850 light years (567.2 parsecs) from Earth in the constellation of Puppis.[5]

Planetary collision event

[edit]

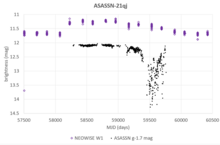

In 2021 the All-Sky Automated Survey for Supernovae reported that this star was rapidly fading. The published Astronomer's Telegram asked for follow-up observations.[6] On twitter the astronomers Dr. Matthew Kenworthy and Dr. Eric Mamajek speculated about this object and amateur astronomer Arttu Sainio made his own investigation and discovered a brightening in NEOWISE data. He then joined the discussion on social media. The star brightened 2.5 years before the dimming event. More contributions came from amateur and professional astronomers, such as spectroscopic follow-up by amateur astronomers Hamish Barker, Sean Curry and the amateur Southern Spectroscopic project Observatory Team (2SPOT) members Stéphane Charbonnel, Pascal Le Dû, Olivier Garde, Lionel Mulato and Thomas Petit. Dr. Franz-Josef Hambsch observed this object with his remote observatory ROAD and submitted his observations to AAVSO. Other observations from professional telescope include ATLAS, ALMA, LCOGT and TESS.[7][2]

In 2023, a scientific paper reported observations consistent with two ice-giant type exoplanets of several to tens of Earth masses having undergone a planetary collision event. The collision occurred at a distance of 2-16 AU (astronomical units) from the star.[3][2] The infrared brightening is thought to be the result of dust produced by the disruption being heated by the collision, reaching a temperature of 1000 K (727°C; 1340°F) and then the dust slowly cooled off and expanded in size. Together with the newly formed planet, the dust cloud orbited the star and 1000 days later the dust moved in front of the star, causing a dimming event. Because of the dust cloud had now reached a large size, the dimming event would last for 600 days. The newly formed planet did not cause a transit.[2]

Another work also studied the event in detail and concluded that the event was produced by the breakup of exocomets.[3] This paper was later mentioned in an author correction of the first work.[8] The system has been observed with JWST, with the data being studied by researchers.[9][10]

A few other planetary collisions were discovered in the past, such as around NGC 2547–ID8,[11] HD 166191[2] and V488 Persei.[12]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Brown, A. G. A.; et al. (Gaia collaboration) (2021). "Gaia Early Data Release 3: Summary of the contents and survey properties". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 649: A1. arXiv:2012.01533. Bibcode:2021A&A...649A...1G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202039657. S2CID 227254300. (Erratum: doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202039657e). Gaia EDR3 record for this source at VizieR.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kenworthy, Matthew; Lock, Simon; Kennedy, Grant; van Capelleveen, Richelle; Mamajek, Eric; Carone, Ludmila; Hambsch, Franz-Josef; Masiero, Joseph; Mainzer, Amy; Kirkpatrick, J. Davy; Gomez, Edward; Leinhardt, Zoë; Dou, Jingyao; Tanna, Pavan; Sainio, Arttu (October 2023). "A planetary collision afterglow and transit of the resultant debris cloud". Nature. 622 (7982): 251–254. arXiv:2310.08360. Bibcode:2023Natur.622..251K. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06573-9. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 37821589. S2CID 263833848.

- ^ a b c Marshall, Jonathan P.; Ertel, Steve; Kemper, Francisca; Burgo, Carlos del; Otten, Gilles P. P. L.; Scicluna, Peter; Zeegers, Sascha T.; Ribas, Álvaro; Morata, Oscar (September 2023). "Sudden Extreme Obscuration of a Sun-like Main-sequence Star: Evolution of the Circumstellar Dust around ASASSN-21qj". The Astrophysical Journal. 954 (2): 140. arXiv:2309.16969. Bibcode:2023ApJ...954..140M. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ace629. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ "2MASS J08152329-3859234". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 2024-08-04.

- ^ Anderson, Natali (2023-10-11). "Astronomers Detect Afterglow of Collision between Two Ice-Giant Exoplanets | Sci.News". Sci.News: Breaking Science News. Retrieved 2023-10-22.

- ^ "ATel #14879: ASASSN-21qj: A Rapidly Fading, Sun-Like Star". The Astronomer's Telegram. Retrieved 2023-12-22.

- ^ "Amateur Astronomers Help Discover Cosmic Crash - NASA Science". science.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2023-12-22.

- ^ Kenworthy, Matthew; Lock, Simon; Kennedy, Grant; van Capelleveen, Richelle; Mamajek, Eric; Carone, Ludmila; Hambsch, Franz-Josef; Masiero, Joseph; Mainzer, Amy; Kirkpatrick, J. Davy; Gomez, Edward; Leinhardt, Zoë; Dou, Jingyao; Tanna, Pavan; Sainio, Arttu (2024-01-01). "Author Correction: A planetary collision afterglow and transit of the resultant debris cloud". Nature. 625 (7993): E1. Bibcode:2024Natur.625E...1K. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06874-z. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 38040870.

- ^ Lock, Simon James; Capelleveen, Richelle van; Kenworthy, Matthew; Temmink, Milou; Crouzet, Nicolas; Picos, Darío González; Kennedy, Grant; Carone, Ludmila; Mamajek, Eric E; Melis, Carl; Hambsch, Franz-Josef; Masiero, Joseph; Mainzer, Amy; Kirkpatrick, J Davy; Gomez, Edward (2024-12-09). "When Worlds (probably) Collide: An exoplanet collision remnant observed around ASASSN-21qj". AGU - Agu24.

- ^ Hill, Marta (2024-12-20). "Telescopes Catch the Aftermath of an Energetic Planetary Collision". Eos. Retrieved 2025-01-02.

- ^ Meng, Huan Y. A.; Su, Kate Y. L.; Rieke, George H.; Stevenson, David J.; Plavchan, Peter; Rujopakarn, Wiphu; Lisse, Carey M.; Poshyachinda, Saran; Reichart, Daniel E. (2014-08-01). "Large impacts around a solar-analog star in the era of terrestrial planet formation". Science. 345 (6200): 1032–1035. arXiv:1503.05609. Bibcode:2014Sci...345.1032M. doi:10.1126/science.1255153. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 25170148.

- ^ Sankar, Swetha; Melis, Carl; Klein, Beth L.; Fulton, B. J.; Zuckerman, B.; Song, Inseok; Howard, Andrew W. (2021-11-01). "V488 Per Revisited: No Strong Mid-infrared Emission Features and No Evidence for Stellar/substellar Companions". The Astrophysical Journal. 922 (1): 75. arXiv:2108.03700. Bibcode:2021ApJ...922...75S. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ac19a8. ISSN 0004-637X.