Zhao Kangmin

Zhao Kangmin (Chinese: 赵康民; Wade–Giles: Chao K'ang-min; July 1936 – 16 May 2018) was a Chinese archaeologist best known for discovering and naming the Terracotta Warriors of the Mausoleum of Qin Shi Huang, one of the most famous archaeological discoveries of the 20th century. Fragments of the warriors were initially found in 1974 by farmers digging a well, but Zhao was officially credited as the discoverer as he was the first to recognize the significance of the fragments and reconstruct them into life-size statues. He also led or participated in many other excavations and served as a longtime curator of the Lintong Museum.

Early life and career

[edit]Zhao was born in July 1936.[1] He worked as a farmer but loved history.[2] In 1961, he was assigned to work at the Lintong County Cultural Center (later Lintong Museum). Lintong, just outside of Xi'an, an ancient capital of China, is rich with archaeological sites, but the museum was tiny and Zhao was its only employee in charge of cultural relics and archaeology.[3] He had no formal education in the field, and largely taught himself archaeology and ancient Chinese scripts by reading journals such as Kaogu and Wenwu and studying the sparse collection of the museum.[3]

In 1962, Zhao excavated three kneeling terracotta crossbowmen,[2] but was unable to date them with certainty.[4] During the Cultural Revolution, when Mao Zedong encouraged the destruction of the Four Olds, the Red Guards destroyed a Qin dynasty statue in the museum, and forced Zhao to publicly criticize himself for "encouraging feudalism".[2]

Discovery of the Terracotta Warriors

[edit]

On 25 April 1974, Zhao received a phone call from Yanzhai Commune (晏寨公社) of Lintong, and was told that farmers in Xiyang Village (西杨) had found terracotta human heads and other fragments.[1][5] Given the location of the village, which was near the Mausoleum of Qin Shi Huang, Zhao immediately recognized its potential significance. He rushed to the village and was told that the relics had been found 28 days before by local farmers digging a well.[3] Yang Zhifa (杨志发) was the first to find a warrior's head, but he initially mistook it as a jar.[1] The farmers, all brothers, threw away most fragments in the field without knowing what they were.[2] Some villagers took pieces as souvenirs, and children played with others as toys.[1]

When Zhao reached the scene, what he saw confirmed his suspicion. He collected all the pieces he could find, even fragments the size of a fingernail. He took them back to the museum, and began putting the body parts together.[1][4] He successfully reconstructed life-size armoured soldiers, and named them "Qin Dynasty Terracotta Warriors". However, he did not report the finding to the national government. The Cultural Revolution was not yet over, and he was worried that the statues were going to be smashed as "Four Olds".[1][4]

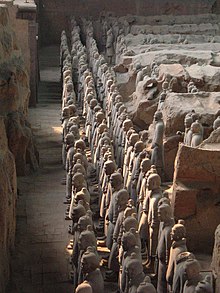

A few months later, Lin Anwen (蔺安稳), a journalist of the Xinhua News Agency heard about the discovery while visiting relatives in Lintong.[5] When Lin visited the museum and saw the restored warriors, Zhao asked him not to write about them. However, Lin ignored his request and publicized the finding when he returned to Beijing.[4][5] The news reached the top of the Chinese leadership, which did not order the warriors' destruction as Zhao had feared. Instead, a formal excavation was organized and more than 500 warriors were unearthed within months.[4]

The discovery of the Terracotta Warriors quickly became known worldwide, and was recognized as one of the world's most important archaeological discoveries of the 20th century.[4] A museum was opened on the site in 1979,[3] which has since attracted visitors from all over the world, transforming sleepy Lintong into a tourism hotspot.[2] In 1990, Zhao was officially recognized by the Chinese government as the discoverer of the Terracotta Warriors.[2]

Later career

[edit]Zhao did not move to the new museum, but remained as curator of the Lintong Museum until his retirement.[2] In the 1980s, he redesigned Lintong Museum in the style of traditional Chinese architecture, but it attracted few visitors.[2]

He led or participated in the excavation of many archaeological sites, including the Neolithic Jiangzhai, other sites in Qin Shi Huang's vast mausoleum complex, the Huaqing Pool, the Tang dynasty Shangfang Pagoda, the Guanshan Tang tomb, and the Ming dynasty tomb of Liu Mao.[3][5] Lintong Museum became filled with his findings, with an entire room devoted to Tang art.[2] He published four books and more than 40 articles in academic journals.[5] His main interest was Buddhist stelae, which filled another room at his museum.[2]

Personal life

[edit]Zhao was married and had two sons. His younger son, Zhao Qi (赵奇), also studied archaeology. According to Zhao Qi, his father was an extremely reticent man who rarely said anything except when discussing archaeology.[6]

Zhao Kangmin died on 16 May 2018, at the age of 81.[1][2][4]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Ives, Mike; Kan, Karoline (2018-05-22). "Zhao Kangmin, Restorer of China's Ancient Terra-Cotta Warriors, Dies at 81". The New York Times. Retrieved 2019-01-29.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Zhao Kangmin died on May 16th". The Economist. 2018-06-07. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2019-01-30.

- ^ a b c d e Cai Xinyi 蔡馨逸; Yang Yimiao 杨一苗 (2018-05-31). ""他把生命交给了考古事业"——记秦兵马俑考古发掘的拓荒者赵康民". Xinhua. Retrieved 2019-01-30.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ponniah, Kevin (2018-05-26). "The man who 'discovered' China's terracotta army". BBC. Retrieved 2019-01-30.

- ^ a b c d e "82岁考古人赵康民病逝:最早认定兵马俑是文物,修复并取名". Thepaper.cn. 2018-05-18. Retrieved 2019-01-30.

- ^ Qu, Chang (2018-06-03). "秦兵马俑考古发现第一人悄然离世". China Youth Online. Retrieved 2019-01-30.