Attempted assassination of Abdul Hamid II

| Attempted assassination of Abdul Hamid II | |

|---|---|

| Part of Armenian national liberation movement | |

| |

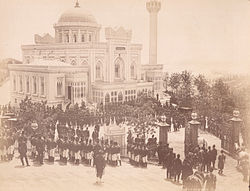

| Location | Yıldız Mosque, Istanbul, Ottoman Empire |

| Date | July 21, 1905 12:45 pm |

| Target | Sultan Abdul Hamid II |

Attack type | Bombing, attempted assassination, mass murder |

| Weapons | vehicle bomb |

| Deaths | 21 |

| Injured | 58 |

| Perpetrators | Armenian Revolutionary Federation Anarchist militants Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (support) |

| Motive | Revenge for the Hamidian massacres To advance anarchism |

| Part of a series on |

| Anarchism |

|---|

|

The attempted assassination of Abdul Hamid II, also known as Operation Nejuik, was an assassination attempt carried out on 21 July 1905 by the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF) and anarchist militants against Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II. The attack was perceived as an act of retribution against the main instigator of the Hamidian massacres (1894–1896), which caused the deaths of 100,000 to 300,000 Armenians. The increasingly unstable situation of the Ottoman Empire, particularly for ethnic and religious minorities who were discriminated against and persecuted, drove them to radicalize progressively. This trend was further facilitated by the introduction of socialism and anarchism into the Ottoman cultural sphere. After a gradual progression in their radicalization, the ARF members decided to assassinate the Sultan, entrusting the organization of the project to their founder and principal theorist, Christapor Mikaelian.

Assisted by Sophie Areshian, Martiros Margarian, Ardaches Seremdjian, Garabed Yeghiguian, the Belgian anarchist couple Anna Nellens-Edward Joris, and the German revolutionary Marie Seitz, Christapor Mikaelian orchestrated the attempt. However, he died while preparing explosives for the project in Bulgaria, which caused significant conflicts within the group and led to a change in strategy. The new approach was deadlier and less certain to kill their target but ensured the safety of the revolutionaries.

The attack was carried out on 21 July 1905 in front of the Yıldız Mosque. The group brought a cart loaded with melinite to the mosque, with Areshian setting the bomb’s timer to explode as the Sultan exited. The attempt failed, not only because it killed 21 people and injured 58 others, but also because Abdul Hamid II emerged completely unscathed.

After the attack, Edward Joris was arrested and sentenced to death, sparking a significant protest movement in Western Europe that ultimately led to his release. The ARF emerged from the attempt with the loss of Mikaelian and a major failure. Many questions remain about the operation.

History

[edit]Context

[edit]During the second half of the 19th century, the Ottoman Empire experienced two parallel phenomena: a growing decline coupled with the modernization of the country.[1] The Empire faced territorial losses due to the gradual independence of several countries, such as Greece (1829) and, in the 1870s, Romania, Montenegro, and Serbia, along with a quasi-independence granted to Bulgaria.[1] These territorial setbacks coincided with increasing incursions by Western powers into the Empire and the introduction of Western concepts such as nationalism and colonialism into Ottoman society. These cultural, economic, and political shocks created an increasingly violent and volatile situation, exacerbated by the legal discrimination imposed by the Ottoman state on ethnic and religious minorities such as Armenians, Greeks, Jews, and Assyrians,[2] who were also subjected to periodic massacres.[2] To maintain control over its colonized regions, including the Caucasus and Armenia, the Empire progressively relied on auxiliaries, typically Kurdish troops composed of pardoned criminals or tribal groups. These forces, known as the Hamidiye, were established by Abdul Hamid II to exert more effective control over the territory, "regulate" the colonized populations,[3] and centralize his Empire.[4] This situation progressively worsened, with numerous massacres being organized, tolerated, or covered up by the Ottoman administration. This culminated in the Hamidian massacres, which resulted in the deaths of between 100,000[5] and 300,000[6] Armenians over two years (1894–1896), foreshadowing the Armenian genocide (1915–1923).[7]

At the same time, the introduction of Western ideologies into the Ottoman sphere brought socialism and anarchism into the Empire.[8] Anarchism, in particular, which aligned well with the anti-colonial struggles of the period,[9] influenced some Armenians, such as Simon Zavarian and Christapor Mikaelian. Both espoused an ideology akin to anarcho-communism and were deeply influenced by Mikhail Bakunin, whose ideas left a lasting mark on them.[10][11] These two activists partnered with Stepan Zorian, another Armenian revolutionary, and together they founded the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF) in Tbilisi in 1890.[12] The organization was quickly influenced by the tactics of direct action, terrorism, and propaganda of the deed, which characterized anarchist movements and attacks in the West at the time.[13] One of their earliest actions of this nature was the occupation of the Ottoman Bank in 1896, conducted with the assistance of revolutionaries from the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO).[14][15] This event marked one of the first hostage-taking terrorist operations in history.[14] However, it ended with a large-scale pogrom organized by Abdul Hamid II, resulting in the massacre of approximately 7,000 Armenians in the capital.[14]

Beginnings

[edit]The Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF) began contemplating the assassination of Abdul Hamid II as early as 1896 in retaliation for the Hamidian massacres.[14] On 22 June 1896, Hovnan Tavtian, the editor-in-chief of Droshak, who was in Geneva at the time,[14][16] wrote to Zavarian suggesting that assassinating the Sultan during the Friday prayer would be a good idea.[14] Zavarian, however, disagreed, arguing that such an attack would be dangerous as it could lead to even greater persecution of Armenians.[14] According to Gaïdz Minassian, the real reason for his reluctance may have been that, in 1896, the ARF lacked the financial resources necessary to undertake such a large-scale operation.[14] In the years that followed, however, the organization gradually strengthened its structure and began collecting a "revolutionary tax" from the Armenian bourgeoisie.[14] This allowed it to amass wealth and eventually consider the operation as a viable option.[14] The violence endured by Armenians during the massacres, the worsening of their situation, and the complete inaction of Western powers led ARF members to radicalize progressively.[14]

In 1898, during its second congress, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF) decided to begin preparations for a large-scale armed uprising that would encompass all the Armenian provinces of the Ottoman Empire.[14] By 1901, the first secret preparations to assassinate Abdul Hamid II were initiated by Mikaelian and the organization's inner circle.[14] In 1904, at its third congress, the ARF officially decided to take action, voting—using cryptic terms—to assassinate Abdul Hamid II.[14] This assassination was planned to coincide with an armed uprising in Sassoun. Unfortunately for the revolutionaries, Ottoman authorities became aware of the attempted insurrection, triggering the 1904 Sasun uprising. This revolt ended in a complete defeat for the insurgents and massacres of Armenians.[14] The ARF also planned to launch guerrilla movements along the Empire's borders to pressure other powers into intervening.[14]

Planning

[edit]

The congress entrusted the organization of the assassination to its co-founder, Christapor Mikaelian (Samuel Fein), and a small group consisting of Ardaches Seremdjian (Torkom), Garabed Yeghiguian (Achod), Martiros Margarian (Safo-Liba Ripps), and Tavtian.[14] Tavtian quickly left the group, but Mikaelian and the remaining conspirators gathered in Piraeus in 1904, where they added more members: Vramshabouh Kendirian (Yervant) and Chris Fenerdjian (Silvio Ricci).[17]

During their stay in Greece, the conspirators were joined by Sophie Areshian (Rubina), who had been invited by Mikaelian after he met her in Baku and was impressed by her.[18] Before her arrival, the revolutionaries convened to discuss whether or not to include women in the assassination’s organization.[18] They ultimately decided that it was better to directly consult the women’s that were concerned by the discussion.[18] On 4 December 1904, Areshian, the German revolutionary Marie Seitz (Emille-Sophie Rips), and a certain "Michelle" joined the discussions.[18] They declared they were fully willing to participate in the project, were offended by the need to even ask, and stated that if necessary, they would organize the attempt themselves.[18] The significant role of women in the ARF is not surprising, given the notable presence of women in far-left movements of the period.[19]

The conspirators then made their way to Constantinople, joining the Ottoman capital. In the city, the seven-member Armenian commando group was, in reality, supported by a broader network established by the organization.[20] This network consisted of fifteen individuals, including four women, who were responsible for logistics.[20] Their tasks included transferring money, explosives, and weapons across different parts of the Empire or from abroad, as well as between the organization’s various safe houses.[20] This logistical team was also tasked with identifying new safe houses and monitoring whether Ottoman intelligence services were tracking anyone.[20] For handling explosives, the ARF maintained connections with Professor Rouher from Geneva, who had prepared the bomb used in 1904 by Yegor Sazonov, an ally of the ARF, to assassinate Vyacheslav von Plehve, the Russian Minister of the Interior.[20] Von Plehve was, among other things, responsible for the confiscation of the Armenian Apostolic Church’s properties.[21] Additionally, the ARF worked with a chemistry professor named Rubanovitch, based in France.[20]

The group also welcomed foreign revolutionaries, such as the Belgian anarchist Edward Joris, who became aware of the Armenians’ plight through Kendirian, his coworker.[20] After forming a friendship with Joris, Kendirian informed the other members of the group about this potential recruit.[20] They were very pleased, both because Joris was an anarchist, which made them believe he would readily join the operation, and because he was Belgian.[20] This nationality offered significant advantages within the Ottoman Empire that were difficult or impossible to obtain as an Armenian.[20] Joris, soon joined by his wife, the anarchist activist Anna Nellens (Bella), was able to move freely within the Empire, transport goods, and access surveilled areas where entry was less restricted for Westerners.[20] These practical benefits likely also explain the organization’s openness to including Marie Seitz in their plans.[20]

The group also dismissed Chris Fenerdjian and ceased collaborating with him after determining that he was prompt to "recklessness".[20] Mikaelian supported the idea of directly targeting the Sultan, if possible, by attacking him during one of his biannual visits to the Dolmabahçe Palace—where the commando would infiltrate and throw bombs at him.[22] This method, inspired by the tactics of the Narodnaya Volya, of which Mikaelian had once been a member, was endorsed by Areshian.[23] It had the advantage of minimizing civilian casualties while increasing the chances of killing the Sultan, though it also posed a significant risk to the commando members.[23] However, conflicts quickly erupted within the organization. Mikaelian[22] and Areshian disagreed with Margarian on the course of action.[23] Margarian preferred to use a cart loaded with explosives in front of the Yıldız Mosque, a strategy that could cause numerous civilian casualties and was more likely to fail, but which would provide greater safety for the revolutionaries.[23] The conflict between the group members was significant, with Areshian accusing Margarian of cowardice.[23] She declared:[23]

I was astonished; how could one be a revolutionary and be afraid of sacrifice and not take advantage of all the positions available?

Ultimately, Mikaelian and Margarian reached an agreement.[22] The assassination was planned as Mikaelian had wished, but it would take place in the diplomatic pavilion adjacent to the Yıldız Mosque. This compromise, however, made the execution of the plan more complicated.[22] Mikaelian, Areshian, and Kendirian left Constantinople to travel to Bulgaria in order to test explosives provided by the anarchist Naum Tyufekchiev.[22][24] Meanwhile, the logistical group that remained in Constantinople managed to import approximately 100kg of melinite from Greece.[22] The cargo, concealed in soap bars weighing 1.2kg each, was recovered and hidden.[22] The group was at risk of being discovered, but Joris succeeded in concealing the contents of the caches before Ottoman police intervened on two separate occasions.[22]

The organization’s plans for the assassination came to a halt with the death of Mikaelian and Vramshabouh Kendirian[25] on 4 March 1905 near Vitocha.[26] Mikaelian and Kendirian were handling explosives[26] when a mishap occurred, while Areshian was present.[27] She witnessed the explosion and, as she called Mikaelian by his affectionate nickname "dad" (Հայրիկ, hayrik in Armenian), she realized he was dying.[27] She closed his eyelids three times before taking control of concealing the incident to prevent the authorities from discovering it.[27] Areshian cleaned the rooms used by the revolutionaries in the hotel where the group had been staying and then transferred the explosives to Boris Sarafov, a leader of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO),[28] who was an ally of the ARF.[27] Sarafov was also close to Naum Tyufekchiev.[29] Meanwhile, in Constantinople, Marie Seitz rejoined Edward Joris, who was deeply affected by the loss of his friend, especially since Mikaelian’s passport was still there.[30] However, the IMRO revolutionaries were able to recover the passport before the police arrived.[30] Together with Joris and Margarian, the three revolutionaries spent a night of mourning and mutual comfort.[30]

Areshian was the only member of the commando to attend Mikaelian's funeral on 10 March 1905.[31] Approximately 6,000 people attended, including Turkish students and Macedonian revolutionaries.[31] Shortly after, Margarian decided to appoint himself as the leader of the group and traveled to Geneva to secure the position.[31] Upon his return, he insisted on his original plan of using a cart filled with explosives, which led to intense conflicts with Areshian.[31] Furthermore, the fact that Kendirian's father was trying to gather information about his son's death from the Armenian Revolutionary Federation and other Armenian circles alerted Joris and the ARF to the imminent risk of the plot being discovered by the Ottoman authorities.[31]

During hesitations about the plan, Areshian once again clashed with Margarian, determined to carry out the operation even if it costed her life.[31] Following this, Joris, who she was staying with, left the room to express his moral disapproval.[31] Areshian then drew lots to decide who in the group would trigger the bomb with Margarian.[31] When the lot fell on her, she was very pleased.[31] The members who would not participate in the commando group left the city even before the assassination attempt began.[32] For instance, Nellens left Constantinople on 20 July 1905, the day before the attack, with 240 francs.[32] She headed to Plovdiv, where the local FRA leader was tasked with helping her go underground and find a job if necessary.[32] The following day, the assassination took place while she was already in hiding.[32] With the preparations complete, the group was ready to carry out the attack.

Attempt

[edit]

The day before the attack, the conspirators gathered the explosives.[25] On the morning of 21 July 1905, they set out in the cart loaded with kilograms of melinite.[25] The excuse chosen by the four members—Areshian, Margarian, Seitz, and the cart driver, Zareh—was to go buy flowers for Areshian, and the group headed toward the mosque.[25] Areshian brought scissors with her, which led to a conflict with Margarian.[25] The scissors would allow her to trigger the explosion instantly by cutting the bomb's mechanism, which he considered "unnecessary and superfluous".[25] She also carried a revolver in case she was arrested.[25]

The group arrived in front of the mosque, and Areshian set the bomb timer for one minute and twenty-four seconds at 12:43:36.[25] They then fled, confident that their mission would be a success.[25] After the attack, Areshian took refuge with three other members of the group near Joris's house, where Seitz kept watch over the comings and goings.[33] Joris had informed the group that he would join them so they could regroup and likely flee together.[33] However, when he arrived, he had lunch without acknowledging them and left the building again without showing any sign of recognition.[33] As time passed, Areshian and the others decided to wait for him until 6:00 PM, the usual time he would leave work and head home.[33]By 6:00 PM, when Joris was still nowhere to be found—he was attending the 75th anniversary of Belgian independence at a private hotel—the group decided to leave at around 7:30 PM, seven hours after the attack.[33] Seitz posed as Margarian's wife, while Areshian pretended to be Zareh's companion.[33] The four of them managed to reach the train station and board the last train to Sofia, helped by Turkish police officers who assisted them in getting their luggage onto the train.[33] On the train, the group was very satisfied, shaking hands and congratulating each other, certain that Abdul Hamid II was dead and that the attack had been a success.[33]

The next day, they learned that the operation had failed.[25] Not only had the group killed 21 people and wounded 58 others, but Abdul Hamid II had come out completely unscathed.[25] He had stopped to speak with Mehmet Cemaleddin Efendi in the mosque before exiting, which ultimately led to his survival.[25]

Suites

[edit]Since most of the conspirators had fled the Ottoman Empire, the death sentences against them were passed in absentia in most cases.[34] After a fairly quick investigation by the Ottoman police, which led to the discovery of Edward Joris's address, he was arrested.[34] He initially defended his innocence, but this stance became complicated.[34] The evidence found at his home was numerous, such as weapons, compromising letters, including one to Dicran Nalbandian, a revolutionary who was arrested by the Ottoman police in Smyrna, where they found 200 bombs.[34] Joris also possessed several copies of Pro Armenia,[34] a pro-Armenian newspaper run by the French anarchist Pierre Quillard.[35] Given the difficulty of his defense, he decided to cooperate partially with the Ottoman authorities, providing them with details about the members of the commando and the group's organization.[34] In reality, the Ottoman police already possessed most of the information Joris gave them.[34] He was eventually sentenced to death after his trial, which sparked a significant movement of protest among anarchists and, more generally, Belgian socialists, leading to the creation of the "Jorisards", a movement linked to the French Dreyfusards that called for Joris's release.[36][37] This movement spread to France, with figures like Georges Clemenceau and Jean Grave supporting his release.[36][38] Grave declared:[38]

Our comrades remember Joris, accused in the plot against the Yldiz-Kiosk bandit, sentenced to death by the judges of the massacrer a year and a half ago. [...] The Armenians are arrested en masse, and Joris, the dangerous and terrible one, who from the depths of his cell makes the bombs dance, will suffer from closer surveillance due to the dirty exploits of the police scum.

The Armenian Revolutionary Federation, on its side, was plunged into chaos. Not only had its founder, main organizer, and thinker, Christapor Mikaelian, died during the preparation of the assassination, but the attack itself also turned out to be a complete failure.[39] Troubles and conflicts over the leadership of the party arose among the revolutionaries.[39] Furthermore, the ARF did little to support the release of Joris.[39] First, the group was facing new imminent threats, such as Russian repression and the Armenian-Tatar massacres, which forced it to refocus on the Caucasus.[39] Deeper reasons might explain this choice, such as the fact that hundreds of Armenian revolutionaries were in Ottoman prisons at the time, and advocating for Joris's release could lead to torture or atrocities against imprisoned revolutionaries.[39] However, it is also possible that the ARF leaders had little trust in Joris.[39] When he was pardoned by the Ottoman Sultan in 1907 and sent back to Belgium, the ARF gave him 700 francs for his medical expenses and distanced itself from him, possibly due to suspicions about the conditions of his release, as the Sultan's spontaneous pardon seemed particularly suspicious to the Armenian revolutionaries.[39]

Unresolved questions

[edit]Gaïdz Minassian raises several unresolved questions surrounding the assassination.[40] First, there is the question of why Joris was spontaneously released from Ottoman prisons.[40]

Furthermore, the day before his death, Mikaelian sent a letter to the Bulgarian general Stoijkov, who was close to Russia, detailing elements of the operation, which raises questions about the purpose of such a letter.[40] This is all the more strange given that no evidence suggests that the operation was directed or organized by Russia.[40]

His death is also suspicious, as he told Areshian that he was particularly careful with the bombs.[40] These bombs, of poor quality, provided by Tyufekchiev and the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO), were suspected by the ARF[18] and could possibly have been deliberately sabotaged to kill Mikaelian.[40] However, Mikaelian was not a bomb maker and had no special training in handling explosives, which could just as well support the theory of an accident, according to Minassian.[40]

In any case, many factions had an interest in seeing the Armenian revolutionary die, according to Minassian, as Mikaelian was a staunch opponent of a union with the Young Turks in a kind of peaceful revolution that would see the Young Turks take power from Abdul Hamid II.[40] He argued that the nationalism of these political movements would be worse than that of Abdul Hamid.[40] These positions were clearly in conflict with the interests of the United Kingdom and France in the region, who preferred to see the Young Turks seize power.[40] After Mikaelian's death, the ARF adopted this union and supported the Young Turk revolution.[40]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Üngör, Ugur Ümit (2012). The Making of Modern Turkey: Nation and State in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1950. Oxford: OUP Oxford. pp. 25–29. ISBN 978-0-19-161908-3.

- ^ a b Wyszomirski, Margaret J. (1975). "Communal Violence: The Armenians and the Copts as Case Studies". World Politics. 27 (3): 438. doi:10.2307/2010128. ISSN 0043-8871. JSTOR 2010128.

- ^ Klein, Janet (2011). The margins of empire: Kurdish militias in the Ottoman tribal zone. Stanford: Stanford University Press. pp. 1–19. ISBN 978-1-5036-0061-4.

- ^ Duguid, Stephen (1973). "The Politics of Unity: Hamidian Policy in Eastern Anatolia". Middle Eastern Studies. 9 (2): 139–155. doi:10.1080/00263207308700236. ISSN 0026-3206. JSTOR 4282467. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 10 January 2025.

- ^ Totten, Samuel; Bartrop, Paul Robert (2008). Dictionary of genocide. Westport (Conn.): Greenwood press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-313-32967-8.

- ^ Akçam, Taner (2006). A shameful act: the Armenian genocide and the question of Turkish responsibility. New York: Metropolitan Books. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-8050-7932-6.

- ^ Adjemian, Boris; Nichanian, Mikaël (30 March 2018). "Rethinking the "Hamidian massacres": the issue of the precedent". Études arméniennes contemporaines (10): 19–29. doi:10.4000/eac.1335. ISSN 2269-5281. Archived from the original on 5 August 2024. Retrieved 10 January 2025.

- ^ Alloul 2018, p. 67-99.

- ^ Alloul 2018, p. 83-86.

- ^ Alloul & Minassian, p. 44-45.

- ^ Tunçay, Mete; Zürcher, Erik Jan, eds. (1994). Socialism and nationalism in the Ottoman Empire, 1876-1923. London ; New York: British Academic Press in association with the International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam. pp. 129–130. ISBN 978-1-85043-787-1.

- ^ Alloul 2018, p. 36.

- ^ Alloul 2018, p. 102-107.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Alloul & Minassian, p. 37-40.

- ^ Karahasanoğlu, Selim (2016). "Anarchists and Anarchism in the Ottoman Empire, 1850-1917". History From Below: A Tribute in Memory of Donald Quataert. Istanbul: Istanbul Bilgi University Press. pp. 553–583. ISBN 978-605-399-449-7. OCLC 961415226.

- ^ "Davthianz, Honan". hls-dhs-dss.ch (in French). Archived from the original on 24 June 2024. Retrieved 10 January 2025.

- ^ Alloul & Minassian, p. 40-41.

- ^ a b c d e f Berberian 2018, p. 57-60.

- ^ Alloul & Minassian, p. 41-42.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Alloul & Minassian, p. 41-45.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 835.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Alloul & Minassian, p. 46-47.

- ^ a b c d e f Berberian 2021, p. 73-74.

- ^ Berberian 2018, p. 66-67.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Berberian 2021, p. 60-66.

- ^ a b Alloul & Minassian, p. 47-50.

- ^ a b c d Berberian 2018, p. 70-71.

- ^ Slavov, Slavi (2012). "Сарафизмьт като течение във Вътрешната македоно-одринска революционна организация". Исторически преглед (in Bulgarian) (1–2): 60–95. ISSN 0323-9748. Archived from the original on 12 August 2023. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- ^ Slavov, Slavi (2012). "Сарафизмьт като течение във Вътрешната македоно-одринска революционна организация". Исторически преглед (in Bulgarian) (1–2): 60–95. ISSN 0323-9748. Archived from the original on 12 August 2023. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- ^ a b c Alloul & Minassian, p. 48.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Alloul & Minassian, p. 49-50.

- ^ a b c d Alloul & Minassian, p. 50-51.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Alloul & Minassian, p. 51-52.

- ^ a b c d e f g Alloul & Minassian, p. 53-56.

- ^ Candar, Gilles; Naquet, Emmanuel; Oriol, Philippe (2009), Manceron, Gilles (ed.), "Pierre Quillard, écrivain, défenseur des hommes et des peuples", Être dreyfusard hier et aujourd’hui, Histoire (in French), Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes, pp. 167–169, ISBN 978-2-7535-6686-6, retrieved 10 January 2025

- ^ a b Alloul & Beyen, p. 225-246.

- ^ Christophe Verbruggen, Schrijverschap in de Belgische belle époque: een sociaal-culturele geschiedenis (Ghent and Nijmegen, 2009), pp. 161-166.

- ^ a b "Les Temps nouveaux". Gallica. 22 June 1907. Archived from the original on 16 November 2023. Retrieved 16 November 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Alloul & Minassian, p. 55-61.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Alloul & Minassian, p. 51-54.

Bibliography

[edit]- Alloul, Houssine (2018). To Kill a Sultan: A Transnational History of the Attempt on Abdülhamid II. United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 978-1-137-48931-9.

- Berberian, Houri (2021). "2 Gendered Narratives of Transgressive Politics: Recovering Revolutionary Rubina". Gendered Narratives of Transgressive Politics: Recovering Revolutionary Rubina. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 53–82. doi:10.1515/9781474462648-006. ISBN 9781474462648. Archived from the original on 19 May 2022. Retrieved 4 January 2025.

- Armenian Revolutionary Federation

- Politics of the Ottoman Empire

- 1905 in the Ottoman Empire

- Mass murder in 1905

- Failed assassination attempts in Asia

- 1900s in Istanbul

- Abdul Hamid II

- July 1905 events

- Beşiktaş

- 1905 in politics

- Armenian national liberation movement

- Mass murder in Istanbul

- Attacks on buildings and structures in Istanbul

- Improvised explosive device bombings in Istanbul

- Attacks on religious buildings and structures in Turkey

- Attacks on mosques in Europe

- 20th-century mass murder in Turkey

- Failed regicides

- Explosions in 1905

- Terrorist incidents in the 1900s

- Terrorist attacks attributed to Armenian militant groups

- Attacks on buildings and structures in the 1900s

- Anarchist terrorism

- Anarchism in Turkey

- Anarchism in Armenia