Women photographers

The participation of women in photography goes back to the very origins of the process. Several of the earliest women photographers, most of whom were from Britain or France, were married to male pioneers or had close relationships with their families. It was above all in northern Europe that women first entered the business of photography, opening studios in Denmark, France, Germany, and Sweden from the 1840s, while it was in Britain that women from well-to-do families developed photography as an art in the late 1850s. Not until the 1890s, did the first studios run by women open in New York City.

Following Britain's Linked Ring, which promoted artistic photography from the 1880s, Alfred Stieglitz encouraged several women to join the Photo-Secession movement which he founded in 1902 in support of so-called pictorialism. In Vienna, Dora Kallmus pioneered the use of photographic studios as fashionable meeting places for the Austro-Hungarian aristocracy.

In the United States, women first photographed as amateurs, several producing fine work which they were able to exhibit at key exhibitions. They not only produced portraits of celebrities and Native Americans but also took landscapes, especially from the beginning of the 20th century. The involvement of women in photojournalism also had its beginnings in the early 1900s but slowly picked up during World War I.

Early participants

[edit]While the work of the English and French gentlemen involved in developing and pioneering the process of photography is well documented, the part played by women in the early days tends to be given less attention.[1]

The beginnings

[edit]Women were however involved in photography from the start. Constance Fox Talbot, the wife of Henry Fox Talbot, one of the key players in the development of photography in the 1830s and 1840s, had herself experimented with the process as early as 1839.[2] Richard Ovenden attributes to her a hazy image of a short verse by the Irish poet Thomas Moore, which would make her the earliest known female photographer.[3]

Anna Atkins, a botanist, was also introduced to photography by Fox Talbot, who explained his "photogenic drawing" technique to her as well as his camera-based calotype process. After learning about the cyanotype process from its inventor, John Herschel, she was able to produce cyanotype photograms of dried algae. She published them in 1843 in her Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, said to be the first book with photographic illustrations.[4]

Another botanist and keen amateur photographer, John Dillwyn Llewelyn, was possibly introduced to photography by his wife Emma Thomasina Talbot, a cousin of Constance and Henry Fox Talbot.[5] She had shown an early interest in photography and did all his printing.[6] Mary Dillwyn, John's younger sister (1816–1906) is considered to be the earliest female photographer in Wales, and the first person to photograph a snowman. Her images of nature and the domestic lives of women and children in 1840s and 1850s 19th century Britain, pushing the boundaries of what could be considered as worthy photographic subjects.[4]

-

Anna Atkins: "Dictyota dichotoma, in the young state; and in fruit" (cyanotype, 1843)

-

Anna Atkins: "Cystoseira granulata" (cyanotype, 1843)

-

Mary Dillwyn, probable self portrait

-

Mary Dillwyn, The Snowman No. 2 c. 1853

The first professionals

[edit]In Switzerland, Franziska Möllinger (1817–1880) began to take daguerreotypes of Swiss scenic views around 1842, publishing lithographic copies of them in 1844. She was also professionally engaged in taking portraits from 1843.[7] Some 20 years later, Alwina Gossauer (1841–1926) became one of the first women professional photographers.[8][9]

In France, Geneviève Élisabeth Disdéri was an early professional in the photography business. Together with her husband, André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri who is remembered for patenting the carte de visite process, she established a daguerrotype studio in Brest in the late 1840s. After Disdéri left her for Paris in 1847, she continued to run the business alone.[10] In 1855, Madame Vaudé-Green opened Photographie catholique, a photography studio in Paris, specialising in photographic paper reproduction of masterpieces of religious paintings, such as Peter Paul Rubens, Fra Bartolomeo and Nicolas Poussin.[11]

Bertha Wehnert-Beckmann was probably Germany's first professional female photographer. In 1843, she opened a studio in Leipzig together with her husband and ran the business herself after his death in 1847.[12] Emilie Bieber opened a daguerrotype studio in Hamburg in 1852. After a slow start, business picked up and she ran the studio until 1885 when she transferred it to her nephew.[13] In 1863, German photographer Emma Kirchner moved to Delft in Holland and opened her studio E. Kirchner & Co.[14]

In the United States, Sarah Louise Judd (1802–1886) is reported to have made daguerrotypes in Minnesota as early as 1848.[15]

In Sweden too, women entered the photography business at an early stage. Brita Sofia Hesselius performed Daguerreotype photography in Karlstad as early as 1845,[16] and Marie Kinnberg was one of the first to use the new photographic technique in Gothenburg in 1851–52.[17] Hilda Sjölin became a professional photographer in Malmö in 1860, opening a studio there the following year,[18] while Sofia Ahlbom also included photography among the arts she practiced in the 1860s.[19] In 1864, Bertha Valerius in Stockholm became official photographer of the Royal Swedish court (later followed as such by her student Selma Jacobsson). During the 1860s, they were at least 15 confirmed female photographers in Sweden, three of whom, Rosalie Sjöman, Caroline von Knorring and Bertha Valerius belonging to the elite of their profession. In 1888, the first woman, Anna Hwass, became a member of the board of the Fotografiska föreningen ('Photographic Society').[17]

Thora Hallager, one of Denmark's earliest women photographers, probably practiced in Copenhagen from the beginning of the 1850s. She is however remembered above all for the fine portrait of Hans Christian Andersen she took in 1869.[20] In Norway, Marie Magdalene Bull opened her studio in the 1850s as well.

In Finland, Caroline Becker of Vyborg and Hedvig Keppler of Turku both opened their studios in 1859, followed by four others until Julia Widgrén became Finland's first famous female photographer in the late 1860s.[21] The Netherlands had its first professional female photographer the same decade, were Maria Hille worked with her spouse in his studio from 1853, and managed it in her own name when she was widowed in 1863.

-

Thun Castle, daguerrotye by Franziska Möllinger (c. 1844)

-

Geneviève Élisabeth Disdéri: Cimetière de Plougastel (1856)

-

Bertha Wehnert-Beckmann: The Wehnert-Beckmann studio (c. 1850)

-

Hilda Sjölin: Portrait of Ida Hultgren (1863)

-

Thora Hallager: Niels Frederik Larsen (1863)

-

Thora Hallager: Hans Christian Andersen (1869)

Pioneering artists

[edit]Two British women are remembered for their early contributions to artistic photography. In the late 1850s, Lady Clementina Hawarden began to take photographs. The earliest images were landscapes taken on the Hawarden estate in Dundrum, Ireland. After the family moved to London, in 1862 she converted the first floor of her South Kensington home into a studio, filling it with props which can be seen in her photographs. She specialised in portraits, especially of her two eldest daughters clad in the costumes of the day. Her work earned her silver medals at the exhibitions of the Photographic Society in 1863 and 1864.[22] Even more widely recognized for pioneering artistic work is Julia Margaret Cameron. Although her interest in photography did not begin until 1863 when she was 48 years old, she consciously set out to ensure photography became an acceptable art form, taking hundreds of portraits of children and celebrities. While her commitment to soft focus was frequently criticized as technically deficient during her lifetime, it later formed the basis for the Pictorialism movement at the beginning of the 20th century and is now widely appreciated.[23][24] Caroline Emily Nevill and her two sisters exhibited at the London Photographic Society in 1854 and went on to contribute architectural views of Kent with waxed-paper negatives.[25] In Italy, Virginia Oldoini, a mistress of Napoleon III, became interested in photography in 1856, recording the signature moments of her life in hundreds of self-portraits, often wearing theatrical costumes.[26]

-

Clementina Hawarden: Her costumed daughters Clementina Maude and Isabella (1861)

-

Clementina Hawarden: Clementina Maude in a dramatic posture (c. 1862)

-

Julia Margaret Cameron: "Sadness" (1864)

-

Julia Margaret Cameron: Portrait of Charles Darwin (1868)

-

Julia Margaret Cameron: "Blackberry Gathering" (c. 1869)

Studio work in the 19th century

[edit]The earliest documented photography studios operated by women in the English speaking world, were opened in the 1860s. Prior to that, there had been studies opened by women in France, Germany, Denmark and Sweden.

In the 1860s and 1870s, women ran independent studios in two locations in Malta. Sarah Ann Harrison operated in her name between 1864 and 1871 from 74, Strada della Marina, Isola (Senglea), Malta.[27] Adelaide Conroy was operating alongside her husband, James Conroy (mentor to the photographer Richard Ellis), from 1872 until around 1880 from premises at 56 and 134 Strada Stretta, Valletta, Malta.[28]

Around 1866, Shima Ryū together with her husband Shima Kakoku opened a studio in Tokyo, Japan.[29] In New Zealand, Elizabeth Pulman assisted her husband George with work in his Auckland studio from 1867. After his death in 1871, she continued to run the business until shortly before she died in 1900.[30]

In Beirut, Lebanon, Marie-Lydie Bonfils and her husband Félix Bonfils established the first photography studio in the area, Maison Bonfils, in 1867.[31] It is unknown how many of the photographs were taken by Lydie but it is thought that she took many of the portraits of women, as women photographers were preferred for modesty.[32] Lydie ran the studio after Félix's death in 1885 until her evacuation to Cairo in 1914 on the Ottoman Empire entering the First World War.[33]

A number of Danish women were quick to open their own studios. Frederikke Federspiel (1839–1913), who had learnt photography with her family in Hamburg, opened a studio in Aalborg in the mid-1870s.[34] Mary Steen opened her Copenhagen studio in 1884 when she was only 28, soon becoming Denmark's first female court photographer with portraits of Princess Alexandra in 1888.[35] Benedicte Wrensted (1859–1949) opened a studio in Horsens in the 1880s before emigrating to the United States where she photographed Native Americans in Idaho.[36]

After studying photography at the London Polytechnic, Alice Hughes (1857–1939) opened a studio in Gower Street, London, in 1891, quickly becoming a leading photographer of royalty, fashionable women and children. At the height of her career, she employed 60 women and took up to 15 sittings a day.[37]

One of the first female photographers to open a studio in New York City was Alice Boughton who had studied both art and photography at the Pratt School of Art and Design. In 1890, she opened a studio on East 23rd Street becoming one of the city's most distinguished portrait photographers.[38] Zaida Ben-Yusuf, of German and Algerian descent, emigrated from Britain to the United States in 1895. She established a portrait studio on New York' s Fifth Avenue in 1897 where she photographed celebrities.[39]

-

Mary Steen: Queen Victoria with Princess Beatrice at Windsor Castle (1895)

-

Frederikke Federspiel with a client in her Aalborg studio (1910)

-

Alice Hughes: Pauline Waldorf Astor (1904)

-

Elizabeth Pulman: Rewi Manga Maniapoto (1879)

-

Zaida Ben-Yusuf: Mrs. Fiske, 'Love finds the way' (1896)

History of Female Photographers in America

[edit]There are several documented instances of women operating studios alone or with their husbands during and prior to the 1860s. One example is Mrs. Elizabeth Beachbard[40] (born c.1822–1828, died 1861) who closed her studio in New Orleans at the onset of the American Civil War to photograph confederates at Camp Moore, Louisiana. She died there of disease in November, 1861 and is buried there.[41] After the huge advancement in culture after the roaring twenties, the number of women photographers increased drastically, estimated to be about 5,000. Despite there still being an apparent line of gender limitations, photography allowed females to bring forth their creativity. Along came many different opportunities including different publications such as "American Amateur Photographer" that allowed for women photographers to further showcase their skills. The emergence of women in photography can be attributed to the progressive era, where the roles of women in our everyday society were changed tremendously and reversed. During this time period, a vast number of women photographers were reportedly part of photography organizations.

The pictorialists

[edit]The use of photography as an art form had existed almost from the very beginning but it was towards the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century that under the influence of the American Alfred Stieglitz its artistic potential, termed pictorialism, became widely recognized.[42] Among Stieglitz' closest associates were Gertrude Käsebier (1852–1934) and Eva Watson-Schütze (1867–1935) who had turned to photography after studying fine art and were committed to developing artistic photography. Their association with Stieglitz led in 1902 to their becoming co-founders of the Photo-Secession movement. They went on to take romantic, yet well composed portraits which were presented at influential exhibitions.[43][44] In addition, Käsebier is remembered for her portraits of Native Americans, soon becoming one of the most widely recognized professional photographers in the United States.[45] Other prominent pictorialists included Käsebier's assistant Alice Boughton and Anne Brigman (1869–1950) with her images of nude women.[46] Mary Devens (1857–1920) who experimented with printing techniques was like Käsebier elected a member of the British Linked Ring which has preceded Photo-Secession in promoting photography as an art form.[47] The German-born Canadian Minna Keene (1861–1943) was also an early female member of the Linked Ring.[48]

-

Gertrude Käsebier: Chief Iron Tail (1898)

-

Eva Watson-Schütze: A Study Head (1900)

-

Anne Brigman: Soul of the Blasted Pine (1908)

-

Gertrude Käsebier: Miss N, portrait of Evelyn Nesbit (1903)

-

Alice Boughton: Two Women under a Tree (1906)

Women photographers from Vienna

[edit]In prewar Vienna, probably more than in any other European city, photo studios managed by women, especially Jewish women, greatly outnumbered those run by men. In all, some 40 women had studios in the city but the most famous of them all was undoubtedly Dora Kallmus (1881–1963).[49] Known as Madame d'Ora, she became a member of the Vienna Photographic Society in 1905 and opened a studio there in 1907. After gaining success with the Austro-Hungarian aristocracy, she opened a second studio in Paris together with her colleague Arthur Benda, dominating the society and fashion photography scene in the 1930s. In addition to their photographic role, Dora Kallmus' studios became fashionable meeting places for the intellectual elite.[50] Other female photographers who embarked on successful careers in Vienna included Trude Fleischmann (1895–1990), who gained fame with a nude series of the dancer Claire Bauroff before moving on to New York,[51] and Claire Beck (1904–1942) who died in a Nazi concentration camp in Riga.[52] Margaret Michaelis-Sachs (1902–1985), who eventually emigrated to Australia, also embarked on her photographic career in Vienna. She is remembered for her scenes of the Jewish market in Kraków taken in the 1930s.[53] Lotte Meitner-Graf

Landscapes and street photography

[edit]Sarah Ladd (1860–1927) began taking landscape photographs in Oregon at the end of the 19th century. Her images of the Columbia River which she developed in a darkroom on a houseboat were exhibited in 2008 at the Portland Art Museum.[54] British-born Evelyn Cameron (1868–1928) took an extensive series of remarkably clear images of Montana and its people at the end of the 19th century. Rediscovered in the 1970s, they were published in book form as Photographing Montana 1894–1928: The Life and Work of Evelyn Cameron.[55]

Laura Gilpin (1891–1979), mentored by Gertrude Käsebier, is remembered for her images of Native Americans and Southwestern landscapes, especially those taken in the 1930s.[56] Berenice Abbott (1898–1991) is best known for her black-and-white photography of New York City from 1929 to 1938. Much of the work was created under the Federal Art Project; a selection was first published in book form in 1939 as Changing New York.[n 1] It has provided a historical chronicle of many now-destroyed buildings and neighborhoods of Manhattan.[57]

In Mexico, Lola Álvarez Bravo (1903–1993) is remembered for her portraits and her artistic contributions intended to preserve the culture of her country. Her works are featured in the collections of international museums including the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. In her own words: "If my photographs have any meaning, it's that they stand for a Mexico that once existed."[58]

-

Evelyn Cameron: Alec Flower, her brother (1898)

-

Sarah Ladd: Early Morning above Vancouver (1905)

-

Laura Gilpin: Mission Church at Rancho de Taos (1930)

-

Berenice Abbott: Blossom Restaurant, New York (1935)

Photojournalism and documentary work

[edit]The Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division preserves millions of images that were created for publication in magazines and newspapers.[59] The Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Online Catalog enables by-name search for images taken by women photojournalists.[60]

Pioneers - late 1800s and early 1900s

[edit]Canadian-born Jessie Tarbox (1870–1942) is credited with being America's earliest female photojournalist, photographing the Massachusetts state prison for the Boston Post in 1899. She was then hired by The Buffalo Inquirer and The Courier in 1902.[61] Zaida Ben-Yusuf was a woman who made a living independently despite the limited number of careers open to women in the twentieth century.[62] The Gerhard Sisters opened their own photograph studio in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1903, with their photographs appearing frequently in local and national media.[63]

-

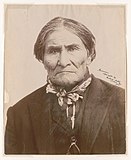

Geronimo (Gerhard Sisters, ca 1904)

-

Weeding beans on a Dutch truck farm outside Winnipeg, Manitoba (Edith S. Watson, ca 1918)

-

Jessie Tarbox Beals at work (1904)

Other pioneers

[edit]Anna Benjamin (1874–1902) was the first female photojournalist to report on a war.[64] Though technically, women were banned from the war zone, she reported on the Spanish-American War for Leslie's Weekly.[65] Harriet Chalmers Adams (1875–1937) was an explorer whose expedition photographs were published in National Geographic. She served as a correspondent for Harper's Magazine in Europe during World War I, the only female journalist permitted to visit the trenches.[66] Another war correspondent based in France during World War I was Helen Johns Kirtland (1890–1979) where she worked for Leslie's Weekly.[67]

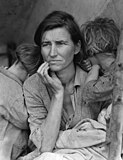

Imogen Cunningham (1883–1976) is known for her botanical photography, nudes, and industrial landscapes. She was a member of the California-based Group f/64, known for its dedication to the sharp-focus rendition of simple subjects.[68] Margaret Bourke-White (1906–1971) was the first foreigner to photograph Soviet industry as well as the first female war correspondent and the first woman photographer to work for Life.[69] During the Great Depression, Dorothea Lange (1895–1965) was employed by the Resettlement Administration to photograph displaced farm families and migrant workers. Distributed free to newspapers, her images became icons of the times.[70] The novelist Eudora Welty also photographed families affected by the Great Depression, especially in rural Mississippi, producing a remarkable body of work.[71]

In the early 1930s, Marvin Breckinridge Patterson (1905–2002) published her world travel photographs in Vogue, National Geographic, Look, Life, Town & Country, and Harper's Bazaar.[72] Marion Carpenter (1920–2002) was the first female national press photographer and the first woman to cover the White House.[73] Edie Harper (1922–2010) was an Army Corps of Engineers photographer during WWII, where she took photographs of different structures on the home front, such as hydro dams and cement test samples. Edie processed the film in the lab for the Corps of Engineers.[74] Photographs from her war work became highly acclaimed and were shown in an exhibition at the Cincinnati Contemporary Art Center in 1961.[75][76]

Mary Ellen Mark (20 March 1940 – 25 May 2015) was an American photographer known for her photojournalism / documentary photography,[77] portraiture, and advertising[78][79] as well as filmmaker. Her specialty was documenting from marginalized communities who were "away from mainstream society and toward its more interesting, often troubled fringes"[80] She had 18 publications produced, most notably Streetwise[81] that also became a documentary with Martin Bell and Ward 81.[82][83] For Ward 81 (1979), she lived for six weeks with the patients in the women's security ward of Oregon State Hospital. Her photos can be found in major magazines in Life, Rolling Stone, The New Yorker, New York Times, and Vanity Fair. In 1977 to 1998, she became a member of Magnum Photos. Besides receiving Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Awards, three fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the 2014 Lifetime Achievement in Photography Award from the George Eastman House and the Outstanding Contribution Photography Award from the World Photography Organisation, she received many other awards of recognition. Vivian Maier (1926–2009) took more than 150,000 photographs, mainly of people and street scenes in Chicago and New York during the 1950s and 1960s, but only became famous in the early 21st century.[84]

-

Dorothea Lange: Migrant Mother (1936)

-

Jessie Tarbox Beals: William Howard Taft at the St. Louis World's Fair (1904)

-

Helen Johns Kirtland: Signing of the Treaty of Versailles in the Hall of Mirrors (1919)

-

Harriet Chalmers Adams: Rio de Janeiro's waterfront and the Morro de Castello from the Ilha das Cobras (1919)

-

Margaret Bourke-White: Aerial photo of the inner city of the destroyed Wurzburg (1945)

Surrealism

[edit]A number of women used photography as a medium for expressing their interest in Surrealism. Claude Cahun (1894–1954) from France is remembered for her highly staged self-portraits which she began taking in the 1920s.[85] Cahun is known for her self portraiture that she used as a way to perform gender identity and playing with surrealism in her work.[86] Croatian-born Dora Maar (1907–1997) also developed her interest in Surrealism in France, associating with André Breton and others. Her vivid portraits from the early 1930s bring out the features of the face as if drawn by an artist.[87] The American Lee Miller (1907–1977) combined her fashion photography with Surrealism, associating with Pablo Picasso in Paris before returning to New York. She created some of the most striking nude photographs of the times.[88]

Surrealism continued to attract the interest of women photographers in the second half of the 20th century. Henriette Grindat (1923–1986) was one of the few Swiss women to develop an interest in artistic photography, associating with André Breton and later collaborating with Albert Camus, with whom she published images of the River Sorgue in the south of France.[89] From the late 1940s, The Czech Emila Medková (1928–1985) began producing surrealistic works in 1947, above all remarkable documentary images of the urban environment in the oppressive post-war years.[90] Though not strictly a Surrealist, the notable Mexican photographer Lola Álvarez Bravo (1907–1993) displayed elements of Surrealism throughout her career, especially in her portraits of Frida Kahlo and María Izquierdo.[91] During her short life Francesca Woodman (1958–1981), influenced by André Breton and Man Ray, explored the relationship between the body and its surroundings often appearing partly hidden in her black-and-white prints.[92] Noted for her experimental alternative-photography techniques and surrealistic imagery, Merry Moor Winnett (1951–1994) created a prolific body of work inspired by artists such as Jerry Uelsmann.[93]

Evolving American participation

[edit]Peter E. Palmquist, who researched the history of women photographers in California and the American West from 1850 to 1950 , found that in the 19th century some 10% of all photographers in the US were women, while by 1910 the figure was up to about 20%. In the early days, most women working commercially were married to a photographer and up to 1890, any woman working on her own was considered to be daring. As the technical process of taking pictures became easier to handle, more amateurs emerged, many participating in photographic organizations.[94] In the 20th century, it was still hard for women to become successful photographers.[95]

Portraits

[edit]Marian Hooper Adams (1843–1885) was one of America's earliest portrait photographers taking pictures of family, friends and politicians from 1883 and doing all the developing herself.[96] Sarah Choate Sears (1858–1935) gained international attention as an amateur photographer after she began producing fine portraits and flower studies. She soon became a member of London's Linked Ring and New York's Photo-Secession.[97] Elizabeth Buehrmann from Chicago (c. 1886–1963) specialized in taking portraits of leading businessmen and prominent society women in their own homes at the beginning of the 20th century, becoming a member of the famous Paris Photo-Club in 1907.[98] Caroline Gurrey (1875–1927) is remembered for her series on mixed-race children taken in Hawaii from 1904. Many were exhibited at the Alaska–Yukon–Pacific Exposition in Seattle.[99] Doris Ulmann (1884–1934) started out as an amateur pictorialist photographer but became a professional in 1918. In addition to portraits of prominent intellectuals, she documented the mountain peoples of the south, especially the Appalachians.[100]

In the 1930s, Consuelo Kanaga (1894–1978) photographed many well-known artists and writers and became one of the few photographers to produce artistic portraits. Her photograph of a slender black women and her children was included in Edward Steichen's Family of Man exhibition in 1955.[101] Ruth Harriet Louise (1903–1940) was the first woman photographer active in Hollywood, where she ran Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer's portrait studio from 1925 to 1930, photographing numerous stars including Greta Garbo and Joan Crawford.[102]

-

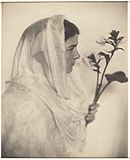

Sarah Choate Sears: Young woman with lilies (c. 1900)

-

Caroline Gurrey: Portrait of a Japanese-Hawaiian and a Portuguese-Hawaiian Boy (1909)

-

Marian Hooper Adams: H. Adams & Marquis (c. 1883)

-

Doris Ulmann: Southern Mountaineer (c. 1928)

-

Ruth Harriet Louise: Greta Garbo (1927)

African-American women in photography

[edit]History

[edit]Photographs are pictures about and of things (Birt). As society has evolved, African-American photographers have been critical in the preservation of authentic portrayals of images about and of black culture. The participation of African-American women in photography began to receive widespread acknowledgment in the mid-20th century and with growing recognition came a shift in focus on social, economic, and political conditions. Some of the most prominent female African-American photographers include Carrie Mae Weems, Lorna Simpson, and Coreen Simpson.

Carrie Mae Weems

[edit]Born in Portland, Oregon, Carrie Mae Weems started her career in 1973 when she received her first camera. Her initial interest in the arts started in 1965, when she met lifelong friend Tom Vinters and began participating in street theater and dance. Though noted as an accomplished photographer, Weems' work spans text, fabric, audio, digital images, installation, and video. "...from the very beginning I've been interested in the idea of power and the consequences of power; relationships are made and articulated through power."[103] When exploring the idea of power, Weems oftentimes uses herself as the subject of her work, not for her own admiration, but "as a vehicle for approaching the question of power..."[103]

Through different mediums, Weems has made it her mission to explore the family relationships, gender roles, the histories of racism, sexism, class and different types of political systems.[104] She was introduced to Dawoud Bey in 1976 and developed a long lasting friendship and professional relationship with the photographer. While on a work trip to Europe, Bey interviewed Weems in BOMB, a magazine focused on artists in conversation.

Lorna Simpson

[edit]Lorna Simpson began her career in fashion photography, taking pictures of people whose style she admired. Simpson was able to develop her skills and became a photojournalist who captured images in politics, culture, music, and sports.

Receiving her education in photography at the School of Visual Arts in New York and the University of California, San Diego, Lorna Simpson was considered a pioneer of conceptual photography well before the peak of her career. Through her work, Simpson aims to challenge the traditional views of gender, identity, culture, history, and memory as viewed by society. Her combination of large-scale photography with meaningful text work together to provide strong visual implications.[105]

Her work can be found in museums across the country at the Museum of Modern Art (New York), the Museum of Contemporary Art (Chicago), and the Walker Art Center (Minneapolis), and many others around the world.

Coreen Simpson

[edit]Making her mark as a photojournalist, Coreen Simpson started her career as a published writer. Her interest in documenting experiences in writing grew into a love for the visual arts when she contacted Essence magazine about an article she wanted to write about a business trip to the Middle East. Although the article was never published, her interest in photojournalism was heightened.

In his article "Coreen Simpson: An Interpretation", Rodger Birt describes looking at a photograph as being "let in on the workings of another human consciousness" allowing for the simultaneous opportunity to receive an authentic depiction of the physical world.[106] Through her work, Simpson has created visual narratives that aesthetically tell the stories of diverse groups of people. Not only is she able to evoke emotional responses through her storytelling, but through design, chiaroscuro, and color as well.

Simpson's friend, Walter Johnson, became one of her biggest mentors and guide as she expanded her knowledge in photography. She also studied Frank Stewart's process and developed a strong capacity for the history of photography. One of her biggest struggles was to differentiate her visual style from those of her inspiration.

The four greatest influences of Simpson's work include Diane Arbus, Baron Adolph DeMeyer, Joel Peter Witkin, and Weegee. Whether conceptually, methodically, or creatively, each of these photographers have contributed to her approach in different ways.[107]

The combination of her admiration for Arbus's uniqueness, Weegee's hunt, DeMeyer's study of the composition, and Witkin's manipulation of the print work together in encompassing the personality of Coreen Simpson's work.[107]

Elizabeth "Tex" Williams

[edit]Elizabeth "Tex" Williams was a World War II military photographer, working in the last year of the war.[108] She was one of the first women to achieve a photography career beyond the mere "camera girl".[95]

International women photographers after the 1950s

[edit]During the second half of the 20the century, illustrated magazines such as National Geographic and photo books found growing world-wide audiences,[109] and some women photojournalists became famous through their work on exotic places and people.[110]

Leni Riefenstahl, a German filmmaker who had made propaganda films for the Nazi regime during the 1930s and 1940s, turned to photography in the 1960s. In her second career, she became known for her pictures of tribal life in southern Sudan through her books Die Nuba (translated as "The Last of the Nuba") and Die Nuba von Kau ("The Nuba People of Kau"). While American photography critic Susan Sontag saw "fascist aesthetics" in these images,[111] and elaborated her kind of criticism of the foreigner's view and interpretation of archaic African lifestyles in her collection of essays On Photography, where Sontag argues that the proliferation of photographic images had begun to establish a "chronic voyeuristic relation" of the viewers to the subjects portrayed.[112] On the other hand, other critics, such as American writer and photographer Eudora Welty reviewed Die Nuba positively.[113] Riefenstahl later also photographed the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich and published photos of underwater life and celebreties like Mick and Bianca Jagger.[114]

Among 14 books published by American photographer Carol Beckwith and Australian Angela Fisher, there are photographs of the Dinka people in southern Sudan and other African ethnic groups like the Maassai that have earned them renown for their aesthetically crafted images of the Dinka's ancient ways of cattle raising.[115] Margaret Courtney-Clarke (born 1949) is a Namibian documentary photographer and photojournalist, living in Swakopmund. Her work "frequently explores the resilience of communities enduring the rapidly shifting landscapes of Namibia", and she has produced a trilogy of books on the art of African women.[116]

Graciela Iturbide (born 1942) from Mexico has had numerous exhibitions and international recognition since the 1970s for her black-and-white photos of Mexican women, often depicting scenes from indigenous communities.[117]

Lesbian women in photography

[edit]History

[edit]Many lesbian women find employment and creative fulfillment as photographers. While lesbians have taken photographs since the medium was invented in 1839, many 19th and early 20th century work by lesbian photographers has been lost, destroyed, or never published because of social stigma against lesbian women. Professional lesbian photographers may have also hidden their sexuality.[118] While all women who worked as professional photographers were seen as defying gender norms, lesbians may have embraced the photography profession as a way to earn money without depending on men.[119] E. Jane Gay (1830–1919) is thought to be the earliest known lesbian photographer.[120][121]

Lesbians also took photos to experiment with self-expression. Lesbians took photos of themselves, their friends, and their lovers embracing each other in intimate settings which hinted at same-sex relationships without being explicitly erotic. Alice Austen (1866–1952) took photos of her friends wearing men's clothing or participating in traditional masculine activities such as smoking. These images were predominantly not for commercial use, instead existing as personal mementos the photographers and models shared with one another.[118][122]

Post-Stonewall

[edit]In the late twentieth century, the second wave feminist movement in the United States and the gay liberation movement following the Stonewall riots inspired efforts to create a cohesive lesbian identity with dedicated cultural artifacts such as explicitly lesbian art, including lesbian photography. These images developed new artistic trends, including depictions of sexual activity and genitalia.[123] Joan. E. Biren (b. 1944) published the first photo anthology of lesbians portraits, Eye to Eye, Portraits of Lesbians, in 1979. Other influential lesbian photographers include Tee Corinne (1943–2006) and Cathy Cade (b. 1942).

Scholars have argued that lesbian artists and activists during the 1970s and 1980s intentionally labeled their art as "lesbian art" in order to foster a sense of community that was distinct from the broader feminist movement. Jan Zita Grover argued that the lesbian identity depicted by this art movement was culturally specific to colonizer societies like the United States and the United Kingdom, and was thus not representative of indigenous systems of gender and sexuality.[124][page needed]

UK women's agency

[edit]In the United Kingdom the women's photographic agency Format was set up in 1983, from an idea conceived by Maggie Murray and Val Wilmer.[125][126] Operating for two decades, until 2003, Format represented women photographers including Jackie Chapman, Anita Corbin, Melanie Friend, Sheila Gray, Paula Glassman, Judy Harrison, Pam Isherwood, Roshini Kempadoo, Jenny Mathews, Joanne O'Brien, Raissa Page, Brenda Prince, Ulrike Preuss, Mirium Reik, Karen Robinson, Paula Solloway, Mo Wilson and Lisa Woollett.[127][128]

21st century

[edit]Contemporary women photographers continue to break ground in the field of photography. Annie Leibovitz captures arresting, usually posed, images of the famous and the unknown, publishing photographs for the covers of Vanity Fair, Vogue, and Rolling Stone, representing a broad survey of American popular culture.[129]

Cindy Sherman's work turns still photography into performance art to explore traditional and pop-cultural myths of femininity. Her work implicitly examines issues of identity and stereotype, representation and reality, the function of mass media, and the nature of portraiture.[130]

The contemporary works of women photographers are numerous. Women-only photography exhibits are controversial yet are argued to be essential to highlight the imbalance of male domination in the field throughout the history of photography, and are becoming increasingly more common.[131][132]

Some contemporary women photographers of note who were born in the 1950s and early 1960s include: Rineke Dijkstra, Nan Goldin, Jitka Hanzlová, An-My Lê, Vera Lutter, Sally Mann, Bettina Rheims, Ellen von Unwerth, JoAnn Verburg and Carrie Mae Weems. Younger contemporary photographers (born in the early 1970s) include Lynsey Addario, Rinko Kawauchi, Hellen van Meene, Zanele Muholi, Viviane Sassen and Shirana Shahbazi.[133] Some recent contemporary photographers include Petra Collins, Juno Calypso, Ilana Panich-Linsman, Delphine Fawundu, Shirin Neshat, Sophie Calle, Laura Aguilar and Genevieve Cadieux.

Awards

[edit]In 1903, Emma Barton (1872–1938) was the first woman to be awarded the Royal Photographic Society medal. It was for a carbon print entitled The Awakening.[134]

The Pulitzer Prize for Photography has been awarded to outstanding work in press photography since 1942. The first woman to receive the award was Virginia Schau (1915–1989), an amateur who photographed two men being rescued from a tractor trailer cab as it dangled from a bridge in Redding, California.[135]

In 2000, Marcia Reed (born 1948), the first female still photographer to join the International Cinematographers Guild also became the first women to win the Society of Operating Cameramen Lifetime Achievement Award for Still Photography in 2000.[136]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The book, with text by Elizabeth McCausland, was republished in 1973 as New York in the Thirties; in 1997 a much larger selection was published as Berenice Abbott: Changing New York.

References

[edit]- ^ Newhall, Beaumont (1982). The history of photography: from 1839 to the present. Museum of Modern Art. ISBN 978-0-87070-381-2. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ Buckland, Gail (1980). Fox Talbot and the invention of photography. D. R. Godine. ISBN 978-0-87923-307-5. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ Maev Kennedy, "Bodleian Library launches £2.2m bid to stop Fox Talbot archive going overseas", The Guardian, 9 December 2012. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ a b Bohata, K (2018). "Pioneers and Radicals: The Dillwyn Family's Transatlantic Tradition of Dissent and Innovation. Transactions of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion" (PDF).

- ^ Marien, Mary Warner (2006). Photography: A Cultural History. Laurence King Publishing. pp. 35–. ISBN 978-1-85669-493-3. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ Michael Pritchard, "Llewelyn, John Dillwyn", Michael Pritchard. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ Hopstock, Katrin. "Franziska Möllinger" (in German). Speyer.de. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ^ "Gossauer, Alwina" (in German). fotostiftung.ch. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ Marc Herren (8 April 2015). "Gossauer, Alwina" (in German). foto-ch.ch. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ Kelly E. Wilder, "Geneviève Élisabeth Disdéri", Oxford Companion to the Photograph. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ^ texte, Cercle de la librairie (France) Auteur du; texte, Bibliothèque nationale (France) Auteur du (17 November 1855). "Bibliographie de la France : ou Journal général de l'imprimerie et de la librairie". Gallica. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ Nicole Schönherr, Straßennamen in Dresden – Reine Männersache? Landeshauptstadt Dresden. Der Oberbürgermeister, Gleichstellungsbeauftragte für Frau und Mann, Dresden 2005, page 32. (in German) Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ^ Rita Bake, "Emilie Bieber", Hamburg.de. (in German) Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ^ "Depth of Field | Scherptediepte". depthoffield.universiteitleiden.nl. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ Palmquist, Peter E.; Kailbourn, Thomas R. (2005). Pioneer Photographers from the Mississippi to the Continental Divide: A Biographical Dictionary, 1840–1865. Stanford University Press. pp. 366–. ISBN 978-0-8047-4057-9. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ^ Värmland förr och nu 1984. Karlstad framför kameran. Bromander, Carl Wilhelm: Från dagerrotypi till kamerakonst. Ett yrkes åttioårshistoria i Karlstad.

- ^ a b Dahlman, Eva: Kvinnliga pionjärer, osynliga i fotohistorien

- ^ "Hilda Sjölin" Archived 7 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Malmö Museer. (in Swedish) Retrieved 12 April 2013

- ^ Wilhelmina Stålberg, P. G. Berg, "Sofia Ahlbom", "Anteckningar om svenska qvinnor" (1864). (in Swedish) Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ^ Tove Hansen, "Kvinders fotografi Kvindelige fotografer i Danmark før 1900", Fund og Forskning, Vol 29 (1990). (in Danish) Retrieved 12 April February 2013.

- ^ Valokuvan taide : suomalainen valokuva 1842-1992 / /toim. / Jukka Kukkonen, Tuomo-Juhani Vuorenmaa, Jorma Hinkka. - Hki : Suomalaisen kirjallisuuden seura, 1992, s. 362-364. - (Suomalaisen kirjallisuuden seuran toimituksia, ISSN 0355-1768 ; 559)

- ^ Mike Merritt, "The Scottish aristocrat whose pioneering photography drew admiration from Lewis Carroll", The Scotsman, 7 February 2013. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ^ "Artistic Portraiture: Julia Margaret Cameron", Woman Photographers, UCR/California Museum of Photography. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ^ "Julia Margaret Cameron's Women" Archived 11 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine, San Francisco Museum of Art. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ^ "Caroline Emily Nevill", Luminous Lint. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ Munhall, Edgar; Whistler, James McNeill; Collection, Frick (1995). Whistler and Montesquiou: the butterfly and the bat. Frick Collection. p. 42. ISBN 9782080135773. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ^ Giovanni Bonello, "More notes for a history of photography in Malta", Times of Malta. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ Tonna, Caroline (2018). "Women and early photography in Malta: Adelaide Conroy and Lucrezia Preziosi". In Abela, Joan; Buttigieg, Emanuel; Attard, Alex (eds.). Parallel Existences. Malta: Kite Publishing. pp. 259–271. ISBN 9789995750565.

- ^ Bennett, Terry. Photography in Japan: 1853–1912, Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle, 2006. ISBN 0-8048-3633-7.

- ^ "Pulman, Elizabeth", Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ Hannavy, John (2008). Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography. New York: Routledge. pp. 173–174.

- ^ Gavin, Carney E. S. (1978). "Bonfils and the early photography of the Near East". Harvard Library Bulletin. XXVI (4): 445–446.

- ^ Chemali, Yasmine (7 March 2014). "The Good Woman named Bonfils". British Library Endangered Archives Programme. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "Frederikke Federspiel (1839–1913)", Dansk Kvindebiografisk Leksikon. (in Danish) Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ^ Tove Thage, "Mary Steen", Dansk Kvindebiografisk Leksikon. (in Danish) Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ^ Aase Bak, "Benedicte Wrensted", in Sys Hartmann (ed.), Weilbachs Kunstnerleksikon, København: Rosinante 1994–2000. (in Danish) Online here. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ^ "Photographic Studio", UCL Bloomsbury project. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- ^ "Obituary for Alice Boughton". Long Island Advance. Brookhaven and South Haven Hamlets. 23 June 1943. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ^ New Exhibition Resurrects Legacy of Groundbreaking Photographer: Ben-Yusuf produced memorable portraits that captured an era published 2 May 2008, www.america.gov. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ "PROJECT Elizabeth Beachbard: Pioneering Ambrotypist in the American Civil War 2018". palmquistgrants.com. PALMQUIST PHOTO RESEARCH FUND.

- ^ "Camp Moore Deaths". Camp Moore Deaths. Camp Moore.

- ^ "Get the Picture: Alfred Stieglitz", Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- ^ "Gertrude Kasebier", Women Photographers, UCR/California Museum of Photography. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- ^ "Eva Watson-Schütze", National Museum of Women in the Arts. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- ^ "'I shall be glad to see them': Gertrude Käsebier's Show Indian Photographs" Archived 3 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- ^ "Anne W. Brigman", The J. Paul Getty Museum. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- ^ Homer, William Innes; Johnson, Catherine (2002). Stieglitz and the Photo-Secession, 1902. Viking Studio. ISBN 978-0-670-03038-5. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- ^ "Keene, Minna", Canadian Women Artists History Initiative. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- ^ "Vienna’s Shooting Girls — Jewish Women Photographers from Vienna", The Times of Israel. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- ^ Lisa Silverman, "Madame d'Ora", Jewish Women Encyclopedia. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- ^ "Fleischmann, Trude", Austria-Forum. (in German) Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- ^ "Claire Beck-Loos und Adolf Loos", Café Marquardt. (in German) Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- ^ Helen Ennis, "Michaelis, Margarethe (1902–1985)", Australian Dictionary of Biography. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- ^ Toedtemeier, Terry (2008). Wild Beauty: Photographs of the Columbia River Gorge, 1867–1957. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press. ISBN 978-0-87071-418-4.

- ^ "Terry" Archived 31 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Visit Montana. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ Martha A. Sandweiss, "Laura Gilpin and the Tradition of American Landscape Photography", Women Artists of the American West. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ "Changing New York: Photographs by Berenice Abbott, 1935–1938", New York Public Library. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- ^ Sills, Leslie (2000). "Lola Álvarez Bravo (1907-1993)". In Real Life: Six Women Photographers. New York, New York: Holiday House. pp. 31–39. ISBN 0-8234-1498-1.

- ^ "Women Photojournalists (Prints and Photographs Reading Room, Library of Congress)". loc.gov. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- ^ "Prints & Photographs Online Catalog". loc.gov. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- ^ "Jessie Tarbox Beals (1870–1942)", The Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Reading Room. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ "Women Photojournalists: Zaida Ben-Yúsuf - Introduction & Biographical Essay (Prints and Photographs Reading Room, Library of Congress)". loc.gov. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- ^ "Women Photojournalists: Gerhard Sisters - Biographical Essay(Prints and Photographs Reading Room, Library of Congress)". loc.gov. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- ^ Eaman, Ross (2009). "Benjamin, Anna (1874-1902)". Historical Dictionary of Journalism. Scarecrow Press. p. 87.

- ^ Prieto, Laura R. (2013). "Benjamin, Anna Northend (1874-1902)". In Frank, Lisa Tendrich (ed.). An Encyclopedia of American Women at War: From the Home Front to the Battlefields. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-59884-444-3.

- ^ "8 Unsung Women Explorers", Yahoo News, 30 April 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ "Helen Johns Kirtland (1890–1979): Biographical Essay", Library of Congress. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ Blaustein, Jonathan (11 December 2014). "An In-Depth History of Group f.64" (Includes slideshow). The New York Times. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ "Margaret Bourke-White" Archived 15 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Women in History. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ Corinna Wu, "American Eyewitness", CR Magazine. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ T.A. Frail, "Eudora Welty as Photographer", Smithsonian magazine, April 2009. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ^ "Women Come to the Front: Marvin Breckinridge Patterson", Library of Congress. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ "Remembering Marion Carpenter" Archived 29 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Associated Press, 25 January 2002. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ Bauer, Marilyn (4 August 2002). "Cincinnati Modernists Reunited". The Cincinnati Enquirer.

- ^ "Visionary Artists at the Carnegie Arts Center :: AEQAI". aeqai.com. Retrieved 2017-03-11

- ^ Villarreal, Ignacio. "Discover the Art of Cincinnati's Own Charley and Edie Harper at the Cincinnati Art Museum". artdaily.com. Retrieved 2017-03-11.

- ^ O'Hagan, Sean (27 May 2015). "Mary Ellen Mark obituary". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ Grimes, William (26 May 2015). "Mary Ellen Mark, Photographer Who Documented Difficult Subjects, Dies at 75". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ^ Dobnik, Verena (26 May 2015). "Beloved Documentary Photographer Mary Ellen Mark Dies at 75". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ^ Long, Andrew. "Brilliant Careers: Mary Ellen Mark", Salon, 28 March 2000

- ^ Saul, Heather (27 May 2015). "Mary Ellen Mark: Renowned documentary photographer dies aged 75". The Independent. London. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ^ O'Hagan, Sean (27 May 2015). "Mary Ellen Mark obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- ^ Laurent, Olivier (26 May 2015). "In Memoriam: Mary Ellen Mark (1940–2015)". Time. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ^ Kotlowitz, Alex. "The Best Street Photographer You've Never Heard Of". Mother Jones. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ Kate Salter, "Claude Cahun: The surreal deal", The Telegraph, 6 January 2008. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ Thynne, Lizzie (1 January 2002). "Claude Cahun: an experimental biopic". Journal of Media Practice. 2 (3): 168–174. doi:10.1386/jmpr.2.3.168. ISSN 1468-2753. S2CID 191603274.

- ^ Donald Goddard, "Dora Maar: Photographer", New York Art World. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ "Lee Miller", V&A. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ "Henriette Grindat or the nonconformist", Journal de la Photographie. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ Krzysztof Fijałkowski, "Emila Medková: The Magic of Despair", Tate, 1 October 2005. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ "Artist Biographies: Lola Alvarez Bravo", Manchester Galleries. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ "Francesca Woodman 1958–1981", Tate. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ Harrison, Cherl (April 2021). Enchanted Realities: The Photography of Merry Moor Winnett (1st ed.). High Point, North Carolina: Barsina Publishing (published 2021). pp. 7–15. ISBN 978-0-9906948-1-6.

- ^ Peter E. Palmquist, "Preface", Women in Photography Archive. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- ^ a b Ellis, Jacqueline (1998). Silent witnesses : representations of working-class women in the United States. Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State University Popular Press. ISBN 9780879727444. OCLC 36589970.

- ^ "Marian Hooper Adams Photographs", Massachusetts Historical Society. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- ^ "Sarah Choate Sears", The J. Paul Getty Museum. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ Goodman, Helen (Winter 1995). "Elizabeth Buehrmann, American Pictorialist". History of Photography. 19 (4): 338–341. doi:10.1080/03087298.1995.10443589.

- ^ Heather Waldroup, "Ethnographic Pictorialism: Caroline Gurrey’s Hawaiian Types at the Alaska–Yukon–Pacific Exposition", Mixed Race Studies. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- ^ "Doris Ulmann Collection", University of Oregon Libraries. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ Barbara Head Millstein and Susan Lowe (1992). Consuelo Kanaga, An American Photographer. Seattle: University of Washington Press. pp. 21–40.

- ^ Dance, R.; B. Robertson, Ruth Harriet Louise and Hollywood Glamour Photography, University of California Press 2002; ISBN 0-520-23347-6.

- ^ a b Bey, Dawoud (Summer 2009). "Carrie Mae Weems". BOMB (108): 60–67. JSTOR 40428266.

- ^ Weems, Carrie Mae. "Carrie Mae Weems". carriemaeweems. Lisa Goodlin Design. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ "Lorna Simpson". Lorna Simpson Studio. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ Birt, Rodger (1987). "Coreen Simpson: An Interpretation". Black American Literature Forum. 21 (3): 289–304. doi:10.2307/2904032. JSTOR 2904032.

- ^ a b Birt, Rodger (Autumn 1997). "Coreen Simpson: An Interpretation". Black American Literature Forum. 21 (3): 289–304. doi:10.2307/2904032. JSTOR 2904032.

- ^ Moutoussamy-Ashe, Jeanne (1993). Viewfinders : black women photographers. New York: Writers & Readers Pub. ISBN 0863161588. OCLC 29733207.

- ^ Carr, David (1 April 2002). "MEDIA: Magazines; Rise of the Visual Puts Words on the Defensive". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ "Behind The Lens With Prizewinning 'Women Of Vision'". text.npr.org. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ "Fascinating Fascism | Susan Sontag". The New York Review of Books. 6 February 1975. ISSN 0028-7504. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ Sontag, Susan (1977). On photography. London: Penguin Books. p. 11. ISBN 9780713911282.

- ^ Welty, Eudora (1 December 1974). "Africa And Paris And Russia". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ "BIOGRAPHY: Leni Riefenstahl Lifetime". 2 July 2014. Archived from the original on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ ""Dinka: Legendary cattle keepers of Sudan". African ceremonies". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ Goldblatt, David (6 February 2018). "The Fragility of Existence". Aperture. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ Nieves, Evelyn; Iturbide, Graciela (8 January 2019). "Graciela Iturbide's Photos of Mexico Make 'Visible What, to Many, Is Invisible'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ a b Corinne, Tee A. (2015). "Photography: Lesbian, Pre-Stonewall". GLBTQ Arts: 1–5.

- ^ Biren, Joan E. (1979). Eye to Eye: Portraits of Lesbians (First ed.). Washington, D.C.: Glad Hag Books. ISBN 0960317600. OCLC 5990685.

- ^ Summers, Claude (2004). The Queer Encyclopedia of the Visual Arts. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-57344-874-1.

- ^ Bernard, Marie Lyn (27 February 2012). "Artists Attack! Ten Lesbian Photographers You Should Know (About)". Autostraddle. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- ^ Muzzarelli, Federica (2 October 2018). "Women Photographers and Female Identities: Annemarie Schwarzenbach, New Dandy and Lesbian Chic Icon". Visual Resources. 34 (3–4): 265–292. doi:10.1080/01973762.2018.1444129. ISSN 0197-3762. S2CID 195016494.

- ^ Eloit, Ilana; Katz, Jonathan (2011). "Lesbians Seeing Lesbians: Building Community in Early Feminist Photography. A historical perspective on the Leslie/Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art exhibition".

- ^ Bolton, Richard, ed. (1989). The Contest of meaning : critical histories of photography. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. ISBN 0262022885. OCLC 19324489.

- ^ "Art, photography & architecture: Wilmer, Val (12 of 13). Oral History of British Photography", British Library, Sounds.

- ^ Amanda Hopkinson, "Raissa Page obituary", The Guardian, 21 September 2011.

- ^ ""Format Photographers Agency 1983–2003"" (PDF). qedstudio.com.

- ^ "Ultimate Format | Format Women Photographers 1983 – 2003", Photofusion.

- ^ "Annie Leibovitz", Infoplease. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ^ "Cindy Sherman", Infoplease. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ^ "Female Artists Are (Finally) Getting Their Turn". The New York Times. 29 March 2016. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ "'Women in Photography' explores diverse possibilities of familiar medium". The Seattle Times. 29 August 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ Friedewald, Boris (2014). Women Photographers: From Julia Margaret Cameron to Cindy Sherman. London: Prestel Publishing Ltd. pp. 8–226. ISBN 978-3-7913-8466-5.

- ^ "The Awakening", The Royal Photographic Society Collection at the V&A, V&A Search the Collections. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ Frank Van Riper, "Pulitzer Pictures: Capturing the Moment", Washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ "PAST SOC LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS". socawards.com. 6 December 2014.

Further reading

[edit]- Gover, C. J. (1988). The Positive Image: Women Photographers in Turn-Of-The-Century America. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-1-4384-0457-8.

- Heron, Liz; Williams, Val (1996). Illuminations: Women Writing on Photography from the 1850s to the Present. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-041-4.

- Hirsch, Robert (2008). Seizing the Light: A Social History of Photography. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-337921-0.

- Lahs-Gonzales, Olivia, and Lucy Lippard. Defining eye: women photographers of the 20th century: selections from the Helen Kornblum collection. The Saint Louis Art Museum, 1997.

- Newhall, Beaumont (1982). The History of Photography: from 1839 to the present. Museum of Modern Art. ISBN 978-0-87070-381-2.

- Rosenblum, Naomi (2010). A History of Women Photographers. Abbeville Press Publishers. ISBN 9780789209986.

- Sullivan, Constance (1990). Women Photographers. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-3950-9.

- Taylor, Roger (2007). Impressed by Light: British Photographs from Paper Negatives, 1840 – 1860 ; [this Publication Accompanies the Exhibition ... Held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, September 24 - December 30, 2007 ... and the Musée D'Orsay, Paris, May 26 - September 7, 2008]. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-1-58839-225-1.

- Tucker, Anne (1973). The Woman's Eye. Knopf, distributed by Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-48678-9.

- Williams, Val. Women photographers: the other observers 1900 to the present. Virago Press, 1986.

- "Finding Aid to the Joan E. Biren Papers, 1944–2011." Five College Archive and Manuscripts Collections. Retrieved 18 April 2019.