Woman Is the Nigger of the World

| "Woman Is the Nigger of the World" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

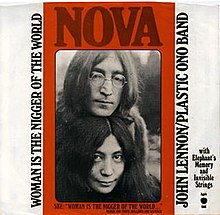

Front cover of the song | ||||

| Single by John Lennon and Yoko Ono as Plastic Ono Band | ||||

| from the album Some Time in New York City | ||||

| B-side | "Sisters, O Sisters" (Yoko Ono) | |||

| Released | 24 April 1972 | |||

| Recorded | November 1971 – March 1972 | |||

| Studio | Record Plant East, New York City | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 5:15 | |||

| Label | Apple | |||

| Songwriter(s) | ||||

| Producer(s) |

| |||

| John Lennon and Yoko Ono as Plastic Ono Band singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

"Woman Is the Nigger of the World" is a song by John Lennon and Yoko Ono with Elephant's Memory from their 1972 album Some Time in New York City. The song was produced by Lennon, Ono and Phil Spector. Released as the only single from the album in the United States, the song sparked controversy at the time due to the use of the word nigger in the title, and many radio stations refused to play the song as a result.

Composition

[edit]The phrase "woman is the nigger of the world" was coined by Yoko Ono in an interview on December 12, 1968, then released on Nova magazine in 1969 and quoted on the magazine's cover, with Ono making the claim that women were the most oppressed group in the world.[3] Literary analysts note that the phrase owes much to Zora Neale Hurston's novel Their Eyes Were Watching God,[4] in which the protagonist Janie Crawford's grandmother says "De nigger woman is de mule uh de world so fur as Ah can see."[5][6] John and Yoko wrote the song in the summer of 1969. Lennon was originally against the statement Yoko made, but when he saw the cover of Nova, it changed his mind.[7] Recording for the song began on February 13, 1972, and ended on March 8 of that year.[8]

In a summer 1972 interview on The Dick Cavett Show, Lennon said that Irish revolutionary James Connolly was an inspiration for the song. Lennon cited Connolly's statement that "the female worker is the slave of the slave" in explaining the pro-feminist inspiration behind the song.[9]

So I said, "Come on Yoko, this is it. I agree with you now. (...) That's what Connolly said. (...) And so we sat down together, and we tried to write the song together as best as we could in a three or four minute song. And it's called Woman Is the Nigger of the World.

Release and reception

[edit]Due to its use of the racial epithet nigger and what was criticized as an inappropriate comparison of sexism to racism against black Americans, most radio stations in the United States declined to play the record.[10][11] It was released in the U.S. on 24 April 1972[12] and peaked at number 57 on the Billboard Hot 100, based primarily on sales, making it Lennon's lowest-charting U.S. single in his lifetime.[13] The song also charted at number 93 on the Cash Box Top 100.[14]

The National Organization for Women (NOW) awarded Lennon and Ono a "Positive Image of Women" citation for the song's "strong pro-feminist statement" in August 1972.[15][3] Cash Box described the song as the "most powerful epic to come out of the women's movement so far."[16]

In the 1 June 1972 issue of Jet magazine, Apple Records ran an ad for the song with a purported quote from Congressman Ron Dellums, a founding member of the Congressional Black Caucus, claiming that he "agreed" with Lennon and Ono that "women are the niggers of the world."[17] In the 15 June issue, Dellums wrote a letter in response rejecting that he had "agreed" with Lennon and Ono. He clarified that "In a white male-dominated society that sees the role of women as bed-partners, broom pushers, bottle washers, typists and cooks, women are niggers in THIS society."[18]

Critique

[edit]Record World said that "with hard rock backing and expert guitar work from Elephant's Memory, John and Yoko deliver the message suggested by the title" and called it "strong stuff, musically and lyrically."[19] The A.V. Club praised the messaging of the song, stating that it "makes a valid point, and one that’s revolutionary for the time".[20] Classic Rock critic Rob Hughes rated it as Lennon's 9th best political song,[21] and Rolling Stone listed the song as one of Lennon's 20 most underrated songs.[1] Conversely, however, Todd Mealy, an author, critiqued the song, and Lennon's defence of the song, as demonstrating "a lack of nuanced and empathetic knowledge" about the past oppression of African-descended people.[22] Ta-Nehisi Coates used the song in a more broader context of race relations, questioning whether Lennon and Ono "really had an understanding of what it meant to be a nigger".[23] Far Out Magazine opined that the song was "blunt, unambiguous, and not memorable enough to truly mean anything".[24]

Response to criticism

[edit]Through radio and television interviews, Lennon described his use of the term nigger as referring to any oppressed person.[9] Apple Records placed an advertisement for the single in the 6 May issue of Billboard magazine featuring a recent statement, unrelated to the song, by prominent black Congressman Ron Dellums to demonstrate the broader use of the term. Lennon also referred to Dellums's statement during an appearance on The Dick Cavett Show, where he and Ono performed the song with the band Elephant's Memory. Because of the controversial title, ABC asked Cavett to apologise to the audience in advance for the song's content; otherwise the performance would not have been shown.[9][12] Cavett disliked giving the statement, saying in the 2010 documentary LENNONYC:

I had John and Yoko on, and the suits said: "We're gonna write a little insert just before the song for you to say." I said, "You are going to censor my guests after I get them on the show? This is ludicrous." So they wrote this thing, and I went in and taped it in order to retain the song. About 600 protests did come in. None of them about the song! All of them about, quote: "that mealy-mouthed statement you forced Dick to say before the show. Don't you believe we're grown up..." Oh, God. It was wonderful in that sense; it gave me hope for the republic.[25]

Lennon also visited the offices of Ebony and Jet magazines with comedian/activist Dick Gregory and appeared in a cover story, "Ex-Beatle Tells How Black Stars Changed His Life", in the 26 October 1972 issue of Jet.[26]

Lennon defended the song, stating: "I know it was political with a capital P, but that was what I had in my bag at the time, and I wasn't just going to throw them away because they were political", before going on to say he still liked the song.[27]

John and Yoko would continue to defend the song in multiple 1980 interviews, including John Lennon's last interview on 8 December 1980.[28] Yoko would continue expressing support for the song, admitting its controversial nature in a 2015 interview.[29]

Reissues

[edit]An edited version of the song was included on the 1975 compilation album Shaved Fish. The song was reissued as the B-side to "Stand by Me" on 4 April 1977.[30] The song is absent from the Gimme Some Truth. The Ultimate Mixes box set,[31] but does appear on the John Lennon Signature Box.[32]

In popular culture

[edit]An episode of the television series Better Things, written by Pamela Adlon and Louis C.K., named "Woman is the Something of the Something", features characters discussing the saying "woman is the nigger of the world".[33]

Chart performance

[edit]| Chart (1972) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Belgium (Ultratop 50 Flanders)[34] | 20 |

| Belgium (Ultratop 50 Wallonia)[35] | 45 |

| Canada Top Singles (RPM)[36] | 73 |

| Denmark (IFPI)[37] | 9 |

| Italy (Musica e dischi)[38] | 12 |

| Japan (Oricon Singles Chart)[39] | 38 |

| Netherlands (Dutch Top 40)[40] | 24 |

| Netherlands (Single Top 100)[41] | 21 |

| US Billboard Hot 100[42] | 57 |

| US Cash Box Top 100[43] | 93 |

Personnel

[edit]Personnel on the single and Some Time in New York City recording are:[44][45][46]

- John Lennon – vocals, guitar

- Stan Bronstein – tenor saxophone

- Gary Van Scyoc – bass

- Adam Ippolito – piano, organ

- Wayne "Tex" Gabriel – guitar

- Richard Frank Jr. – drums, percussion

- Jim Keltner – drums

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Fricke, David (10 December 2010). "20 Underappreciated John Lennon Solo Songs". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 3 October 2023. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

Lennon set his soapbox vocal and underground-wire-service lyrics to a hearty retro blast of American Fifties R&B.

- ^ Blaney, John (2005). John Lennon: Listen to This Book. John Blaney. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-9544528-1-0. Archived from the original on 2 April 2024. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

Lennon's feminist anthem was inspired by something she [Ono] said in a Nova magazine interview in 1969.

- ^ a b Perlman, Allison (May 2016). Public Interests: Media Advocacy and Struggles Over U.S. Television. Rutgers University Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-8135-7232-1. Archived from the original on 2 April 2024. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ Chang, Jeff (2014). Who We Be: A Cultural History of Race in Post-Civil Rights America. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-312571-29-0.

- ^ Hurston, Zora Neale (1986). Their Eyes Were Watching God. London: Virago Press. p. 19. ISBN 9780860685241.

- ^ Rees, Nigel (2002). Mark My Words: Great Quotations and the Stories Behind Them. New York: Sterling Publishing. p. 418. ISBN 0-760735-32-8.

- ^ a b Burger, Jeff; Lennon, John (15 May 2017). Lennon On Lennon: Conversations With John Lennon. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-78323-904-7. Archived from the original on 2 April 2024. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ Doggett, Peter (17 December 2009). The Art And Music Of John Lennon. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-85712-126-4. Archived from the original on 2 April 2024. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d Television interview, 11 May 1972. The Dick Cavett Show: John and Yoko collection [video recording] DVD, 2005. ISBN 0-7389-3357-0.

- ^ Hilburn, Robert. "New Disc Controversy" Los Angeles Times 22 April 1972: B6

- ^ Kahn, Jamie (24 April 2022). "The John Lennon track that radio stations refused to play". Far Out Magazine. Archived from the original on 24 January 2024. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ a b Miles, Barry; Badman, Keith, eds. (2001). The Beatles Diary After the Break-Up: 1970–2001 (reprint ed.). London: Music Sales Group. ISBN 978-0-7119-8307-6.

- ^ Duston, Anne. "Lennon, Ono 45 Controversial" Billboard 17 June 1972: 65

- ^ Blaney, John (2005). John Lennon: Listen to This Book (illustrated ed.). [S.l.]: Paper Jukebox. p. 326. ISBN 978-0-9544528-1-0.

- ^ Johnston, Laurie. "Women's Group to Observe Rights Day Here Today" New York Times 25 August 1972: 40

- ^ "CashBox Record Reviews" (PDF). Cash Box. 6 May 1972. p. 18. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 March 2022. Retrieved 11 December 2021.

- ^ "Jet". Jet. 42 (10). Johnson Publishing Company: 61. 1 June 1972. ISSN 0021-5996. Archived from the original on 7 February 2023. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- ^ Dellums, Ronald V. (15 June 1972). "Rep. Dellums Objects to Quote in Record Ad". Jet. Johnson Publishing Company. Archived from the original on 7 February 2023. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- ^ "Hits of the Week" (PDF). Record World. 5 May 1972. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 February 2023. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- ^ "Woman is the what of the world? 8 image-altering John Lennon songs". The A.V. Club. 11 October 2013. Archived from the original on 22 September 2023. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ Hughes, Rob (8 December 2021). "John Lennon's 10 best political songs". Classic Rock. Louder Sound. Archived from the original on 8 December 2021. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ Mealy, Todd M. (3 May 2022). The N-Word in Music: An American History. McFarland & Company. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-4766-8706-3. Archived from the original on 2 April 2024. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ Coates, Ta-Nehisi (15 November 2011). "Shirley Chisholm, Cont". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

Did Yoko Ono and John Lennon really have a deep understanding of what it meant to a "nigger?" Were they even interested? Or were they just looking to wedge an entire people into their need for a symbol?

- ^ Golsen, Tyler (12 June 2022). "John Lennon and Yoko Ono's 'Some Time in NYC' turns 50". Far Out Magazine. Archived from the original on 24 January 2024. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ 2010 documentary LennoNYC

- ^ "Happy Birthday, John Lennon: Re-examining a flawed icon". The Seattle Times. 8 October 2020. Archived from the original on 2 July 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ White, Richard (30 June 2016). Come Together: Lennon and McCartney in the Seventies: Lennon and McCartney In The Seventies. Omnibus Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-78323-859-0. Archived from the original on 2 April 2024. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ Wiener, Jon (8 December 2010). "Lennon's Last Interview: 'The Sixties Showed Us the Possibility'". ISSN 0027-8378. Archived from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

'I'm more feminist now than I was when I sang "Woman Is the Nigger of the World",' he said. 'Isn't it time we destroyed the macho ethic? ... Where has it gotten us all of these thousands of years?'

- ^ Charlton, Lauretta (2 October 2015). "Yoko Ono on How to Change the World, Her Most Controversial Work, and John Lennon's 75th Birthday". Vulture. Archived from the original on 3 October 2023. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

Oh yeah, that was very controversial. What John and I were really trying to say was, 'Okay, women are not treated well.' That"s what it meant, you know? And it's a very interesting thing.

- ^ Blaney, John (2005). "1973 to 1975: The Lost Weekend Starts Here". John Lennon: Listen to This Book (illustrated ed.). [S.l.]: Paper Jukebox. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-9544528-1-0.

- ^ Borack, John M. (3 May 2021). "John Lennon's 'Gimme Some Truth' Box - The Ultimate or No?". Goldmine Magazine: Record Collector & Music Memorabilia. Archived from the original on 2 April 2024. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ Gaar, Gillian (16 June 2015). "John Lennon: Lennon Box Set". Paste Magazine. Archived from the original on 2 April 2024. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ Felsenthal, Julia (30 September 2016). "Pamela Adlon on Better Things's Most Meta Episode Yet". Vogue. Archived from the original on 2 October 2016. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- ^ "John Lennon / Plastic Ono Band With Elephant's Memory And The Invisible Strings – Woman Is the Nigger of the World" (in Dutch). Ultratop 50.

- ^ "John Lennon / Plastic Ono Band With Elephant's Memory And The Invisible Strings – Woman Is the Nigger of the World" (in French). Ultratop 50.

- ^ "Top RPM Singles: Issue 7673." RPM. Library and Archives Canada.

- ^ "Hitlisten". Ekstra Bladet. 28 September 1972. p. 34.

- ^ Spinetoli, John Joseph. Artisti In Classifica: I Singoli: 1960-1999. Milano: Musica e dischi, 2000

- ^ Okamoto, Satoshi (2011). Single Chart Book: Complete Edition 1968–2010 (in Japanese). Roppongi, Tokyo: Oricon Entertainment. ISBN 978-4-87131-088-8.

- ^ "Nederlandse Top 40 – John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band With Elephant's Memory And The Invisible Strings" (in Dutch). Dutch Top 40.

- ^ "John Lennon / Plastic Ono Band With Elephant's Memory And The Invisible Strings – Woman Is the Nigger of the World" (in Dutch). Single Top 100.

- ^ "John Lennon Chart History (Hot 100)". Billboard.

- ^ "Top 100 1972-06-03". Cashbox. Archived from the original on 4 March 2013. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ Blaney, J. (2007). Lennon and McCartney: together alone : a critical discography of their solo work. Jawbone Press. pp. 60–62. ISBN 978-1-906002-02-2.

- ^ "Woman Is The N—r Of The World". The Beatles Bible. 3 August 2010. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ^ Pieper, Jörg (17 May 2009). The Solo Beatles Film & TV Chronicle 1971-1980. Lulu.com. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-4092-8301-0. Archived from the original on 2 April 2024. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- 1972 songs

- 1972 singles

- John Lennon songs

- Apple Records singles

- Songs written by John Lennon

- Songs written by Yoko Ono

- Song recordings produced by Phil Spector

- Song recordings produced by John Lennon

- Song recordings produced by Yoko Ono

- Song recordings with Wall of Sound arrangements

- Songs with feminist themes

- Race-related controversies in music

- Plastic Ono Band songs

- Naming controversies