Wolfgang Kaiser (KgU)

Wolfgang Kaiser | |

|---|---|

| Born | 16 February 1924 |

| Died | 6 September 1952 (aged 28) Münchner Platz Prison, Dresden, East Germany |

| Cause of death | Execution by guillotine |

| Nationality | German |

| Occupation(s) | Civil rights militant KgU technical supporter Show trial victim |

Wolfgang Kaiser (16 February 1924 – 6 September 1952) was a member of Rainer Hildebrandt's "Struggle against Inhumanty" group (KgU / Kampfgruppe gegen Unmenschlichkeit) which campaigned against the one party dictatorship in the German Democratic Republic.

In the 1952 Hildebrandt conspiracy show trial, he was identified on 8 August as the "chief chemist" of the KgU and, on 9 August, condemned to death in the country's Supreme Court.[1]

Life

[edit]Background

[edit]Wolfgang Kaiser was a chemistry student. He was studying at the Humboldt University, then in East Berlin, though he actually lived in West Berlin. The political division of Berlin complicated his life. He attempted without success to switch to the newly established Free University in West Berlin, but lost his student place in the process.[2]

The "Struggle against inhumanity group" "Die KgU" / "Die Kampfgruppe gegen Unmenschlichkeit")

[edit]Now unemployed, Kaiser offered his services as a chemicals expert to the recently established KgU, with which he was politically in sympathy. From early 1951 the KgU placed a former multi-occupancy rabbit hutch at his disposal, in the garden of their premises in Berlin's Nikolassee district. Later his work as the KgU's chemistry expert transferred to three basement rooms in an apartment which the movement rented at Kurfürstendamm No.106, in the city's central Halensee district. Kaiser continued through this time to receive unemployment benefit: he was not an employee of the KgU. He did, however, receive a small honorarium from them, initially of 50 Marks per month, and which in May 1951 was doubled to 100 Marks.

Kaiser made fuses for "leafleting balloons", which the KgU used in order to rain down, in large quantities, leaflets, newspapers and other reading material onto the German Democratic Republic.[3] He also produced smoke grenades, stink bombs and incendiary materials which could be used to torch targets such as propaganda noticeboards. The incendiary material was kept in small ampoules, each with a capacity of approximately two cubic centimeters, which the "Resistance Department" of the KgU could distribute to activists. In his rooms Kaiser kept a large number of these ampoules which he seems to have used in experiments involving small quantities of all sorts of chemicals that he got hold of, including the nerve agent Cantharidin.

The "Ministry for State Security" ("Das MfS" / "Das Ministerium für Staatssicherheit" or, colloquially, "The Stasi")

[edit]Kaiser's activities and his identity were known to the East German Ministry for State Security (the Stasi) through an undercover Stasi informer called Gustav Buciek. The KgU had been using Buciek as a messenger since 1951. Even after he took a job with the Telegraf newspaper , Buciek's criminal past, which was unknown to his employer, still enabled the Stasi to blackmail him.[2] According to Buciek's reports, Kaiser's improvised laboratory contained neither laboratory equipment nor chemistry related materials.[2]

Kaiser purchased the chemicals for his experiments and other activities from a shop called Drogerie Gläser. The shop owner was another undercover Stasi informer. From time to time Kaiser, when buying his supplies, would let drop a remark about some forthcoming "big event", and the conversation would be reported to the Stasi by "Secret agent Gläser". Matching the reports from Busiak with Gläser's information about the nature and quantities of his supplies, the Stasi were able to infer that Kaiser was purchasing items such as invisible ink, explosives, metal dissolving acids and other items suitable for planning and carrying out acts of sabotage.

The Stasi employed a third undercover informer, named Baumbach, on Wolfgang Kaiser's case. Baumbach was a friend from college days, whom they had originally mandated to use political arguments in order to dissuade Kaiser from his KgU activities. In the end Baumbach identified himself to Kaiser as a "senior Stasi operative" and was paying Kaiser, whose alcohol fueled life-style left him permanently short of money, small amounts of 20 or 30 Marks in return for information about the KgU.[2] The Stasi found out from "Secret agent Gläser" that Baumbach had blown his own cover to Kaiser, and they also knew that he was supplying incomplete reports on Kaiser to his Stasi contact. After Kaiser had disclosed to Baumbach plans for a KgU mass leaflet drop scheduled for 1 May 1952, Baumbach offered him the opportunity to resume his studies at the Humboldt University provided he would at the same time collaborate with the Stasi (bei gleichzeitiger „Zusammenarbeit mit dem MfS“).

Arrest

[edit]On 8 May 1952, at three o'clock in the morning, Wolfgang Kaiser, probably acting under the influence of alcohol, armed himself with a pistol, a baton, and a drugged cigarette. Accompanied by "Agent Baumbach" who was similarly armed, he then presented himself at an East Berlin Police station and accepted the offer that Baumbach had supposedly delivered from the Stasi. The two of them were arrested.

The charges

[edit]Charges (which disclosed the extent of the surveillance under which he had been operating) laid against Kaiser the next day, were to the effect that he had endangered world peace and carried out acts of sabotage and diversionary actions, while acting as an agent of the "Ildebrandt'schen" [i.e. relating to Rainer Hildebrandt] "Terror and Espionage organisation" [ie the KgU]. He had produced explosives, phosphorus ampoules, incendiary stuff etc. in order to carry out acts of sabotage.[4] Following their arrest Kaiser and Baumbach were handed over to the Stasi.[2]

After the Stasi investigators had established that Kaiser was not known to any of the prisoners with KgU contacts in East German jails, they sent Kaiser for trial in the Supreme Court, where he was to be confronted by evidence from three other KgU members from East Germany, these being the Müller couple from Zerpenschleuse and Kurt Hoppe, a finance worker from Potsdam.

Evidence gathering

[edit]Joachim Müller had undertaken an unsuccessful arson attack against a temporary wooden Autobahn bridge at Finowfurt,[5][6] he had successfully employed a stink-capsule to make a polling station unusable. he had scattered "tyre destroyers" on the road, and he was intending to blow up the old lock along the recently opened Havel Canal at Paretz. His wife, Ursula, had been a "courier", providing a link to the KgU. Under interrogation the Müllers confessed to a lengthy list of planned and/or enacted sabotage schemes, of which hardly any had been crowned with success. Ursula Müller stated that a KgU member, "most likely" Ernst Tillich, at that time the campaigning group's leader,[1] would have wished to drive a car to Finowfurt with a petrol/gasoline canister, incendiary equipment and "tyre destroyers" in support of a plan to burn down the nearby "Kaiser Bridge".[2] Sabotage tools, including incendiary devices, for Müller and other unknown saboteurs had, on his own admission, been produced by Kaiser.

Hoppe had facilitated "administrative damage" to the East German economy by helping the KgU with the distribution of financially sensitive "news items", original forms and printed circulars. The Müllers and Hoppe were not known to each other.

Trial

[edit]Pretrial

[edit]The defendants were imprisoned in an underground cell (known as a "submarine") at the main Stasi prison, Hohenschönhausen, and here the Stasi prepared them for the trial process.[7] It was here that Chief State Prosecutor Melsheimer, witnessed by a Soviet officer, threatened Müller that he would ask the court to apply the death sentence if Müller failed to testify in line with the indictment.[2][8] At the same time the Supreme Court vice-president Hilde Benjamin, who would herself be presiding at the trial, gave notice in a pretrial meeting with the defense lawyers, whose participation in the actual trial proceedings would be minimal,[9] that they should not expect any death sentences.[10]

Public justice

[edit]The trial of Wolfgang Kaiser began in the Supreme Court, presided over by the Court's Vice-president, Hilde Benjamin, on 8 August 1952. Publicity was maximised with numerous journalists present from both west and east. Extracts of the proceedings were even broadcast on the radio. The lawyer who was there to defend Kaiser, a Dr.Büsing (who later defected to the west), had the impression that the Stasi had "prepared" ("behandelt") the defendants.[9] During their "preparation" they had been "incriminated over things that had not been known to the defense, and which could not be found in the papers filed with the court" ("„mit Dingen belastet, die weder der Verteidigung bekannt waren, noch dem Akteninhalt entnommen werden konnten"). Ernst Melsheimer, who was prosecuting, presented Kaiser as the "Chief of the KgU's chemical-technical lanboratory" (der "Leiter des chemisch-technischen Labors der KgU"). He referred to Johann Burianek who had been executed at the beginning of August, following conviction in another show trial based on alleged KgU sabotage plans. He produced an expert witness who testified that the potassium chlorate and ammonium nitrate in the possession of Kaiser and the "explosives case" passed to Burianek were not suitable to blow up the railways bridge, but might at the most dissolve the rails. Melsheimer invited the court to conclude, therefore, that the possible torching of the bridge was no more than a "bravura scenario", and his expert witness did not refute Melsheimer's inference.[11]

Nerve agent

[edit]

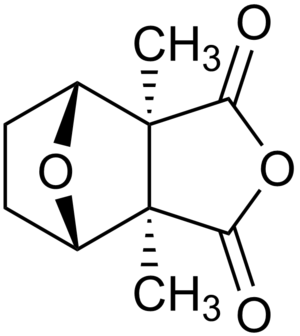

Merlsheimer showed particular interest in 25 gm of the nerve agent cantharidin that Kaiser had acquired. Although the Resistance Department of the KgU had issued doses of the poison to some of their contacts in East Germany, there was no evidence that any had been used,[12] which meant that this line of attack could be presented to the court only in terms of what might theoretically be possible. Melsheimer explained, however, that under a best case scenario, administering doses intravenously ("bestmöglicher intravenöser Anwendung"), 25,000 people could be killed with Kaiser's cantharidin.

Conviction and sentencing

[edit]According to the defence lawyer Büsing, on the second day of the trial, during a break in the proceedings that came just before the pleadings of Prosecutor Melsheimer, the presiding judge, Hilde Benjamin explained that Kaiser would have to be sentenced to death "on the instruction of [...her] friends" ("auf Anweisung [...ihrer] Freunde").[10] The friends in question were the Soviet advisers observing the trial. In support of the sentence the judge went through all the KgU plans and projects, which the prosecutor had set out before the court in such abundance. That none of the dastardly plans ("hinterhältigen Pläne") had actually been carried out was, in the court's judgement, reason to be grateful for the vigilance of the security services.[13] That day, 9 August 1952, the Supreme Court handed down the death sentence to Wolfgang Kaiser, the "incorrigible enemy of the hard working people" ("unverbesserlichen Feind des werktätigen Volkes"). Müller received a life sentence while his wife was given ten years and Hoppe twelve years in prison.[14]

Much later Kaiser's co-defendant, Joachim Mueller went public with his own recollections. Mueller said that Kaiser had believed, on the basis of promises received from the Stasi, that the death sentence would be pronounced only for show. As the trial unfolded Kaiser had told Mueller that he had a "luxury cell", and that he had been promised immunity so long as he was ready to testify against the KgU.[15]

Appeals and execution

[edit]There is no sign of any formal appeals process being invoked, but on 15 August 1952 Wolfgang Kaiser's father, who lived in West Berlin, wrote a letter to Wilhelm Pieck, the East German president, begging for clemency. He enclosed two doctors' confirmations of the nervous disorders for which his son was being treated.[16] Judge Benjamin's reply to the president on 18 August indicated scepticism regarding the sanity argument. On 1 September the Chief Prosecutor, Merlsheimer, received a letter of appeal on behalf of the Evangelical Church, written by Heinrich Grüber. Grüber hoped the death sentence could be replaced by a life imprisonment, but if the execution must go ahead he begged that Kaiser might be afforded spiritual support. Meanwhile, Merlsheimer's office wrote to Kaiser's father on 5 September calling him to a meeting.

However, on 5 September 1952 Kaiser died, without spiritual support, on the guillotine (″Fallschwertmaschine″) at the country's Central Execution location on the Münchener Platz in Dresden. He died before Merlsheimer's invitation to a meeting had reached his father (who begged to be excused from attending on health grounds: no more is known).[17]

The application made at the time by Dr. Walter Friedeberger, the director of the German Hygiene (medical) Museum in Dresden, for permission to "recover the human organs" of Kaiser and Burianek was rejected.

1952 Context

[edit]The times

[edit]Very shortly before the Kaiser trial the Supreme Court of East Germany had for the first time invoked Article 6 of the Constitution, in a related case, to impose its first death sentence on Johann Burianek, another KgU member. The background to the series of show trials held in East Berlin during 1952 was the "orderly construction of socialism" ("planmäßigen Aufbaus des Sozialismus") announced by General Secretary of the Central Party Committee Walter Ulbricht in July 1952 at the second conference of the Socialist Unity Party. All this was happening in a climate of "enhanced revolutionary vigilance" ("Erhöhung der revolutionären Wachsamkeit") and "intensification of class struggle" ("Verschärfung des Klassenkampfes").[3] Simultaneously the German Democratic Republic was being cut off with measures that included progressively closing the external borders of West Berlin (left by the post-Second World War settlement as a western enclave surrounded by East German territory) and the splitting of the Berlin telephone network at the end of May in response to growing threats from outside the country.[18]

The propaganda war

[edit]By 1952 the division of what had remained of Germany into two countries had become fact: West Germany comprising the zones formerly occupied by the United States (southern Germany), Britain (northern Germany) and France on one side and East Germany, comprising what had previously been known as the Soviet occupation zone of Germany on the other. From the East German perspective, the Kampfgruppe gegen Unmenschlichkeit (KgU / "Struggle Against Inhumanity" group) looked like a terrorist organisation led by the American spy agencies and the defendants, its members, had planned acts of sabotage, murder and terrorism. The "brutality and sadism" of Kaiser and the others convicted "knew no bounds. ..... Even the lives and health of women and children were threatened by them". (" ihre Brutalität und ihr Sadismus kennen keine Grenzen ... selbst Leben und Gesundheit von Frauen und Kindern sind von ihnen bedroht“".)[3] In later discussions on the KgU, the "Poison alchemist Kaiser" and the "Rail bomber Burianek" were named in the same breath.[19] Even though no evidence for the demolition of anything by the KgU existed,[20][21] and no name for any East German official supposedly targeted for murder was ever produced, the trial and its aftermath made an impression with public opinion in the west. By the end of the 1952, those people who had followed the show trials were very far from convinced that the communist accusations were completely groundless.[3] Some of the revelations about the KgU presented in West Germany's news magazine Der Spiegel during the 1950s involved matters that were already in the public sphere thanks to East German propaganda.[3]

The KgU's "dumb scheme", intending to use poison in their struggle, gave the group a "poison problem"[22] that would haunt them. Plans, which came out at the Kaiser and Burianek trials, involving incendiary devices and suitcase bombs were one thing; but by concentrating the attention of the court (and of those reporting it) on the possible uses of Kaiser's 25gm of nerve agent, the East German Prosecutor was able to destroy sympathy and trust for the KgU, on account of the resistance tactics they were evidently willing to contemplate, across western public opinion. East German propaganda used these high-profile show trials to criminalize all sorts of opposition: the US Intelligence services were always behind the conspiracies "proven".

The Party journalist-politician Albert Norden described West Berlin as a "vipers' nest", that provided the gangsters, who "want to make the lives of the Germans hellish" ("die das Leben der Deutschen zur Hölle machen sollen"). The ruling SED (party) developed a scapegoat theory which traced the country's economic difficulties, its failings, and even the uprising of 17 June 1953 back to the show trials of 1952.[3]

It was not till 3 June 1954, during preparations for the first anniversary of the 1953 uprisings, that a Stasi spokesman mentioned Wolfgang Kaiser's execution. He did not say exactly when it had taken place.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Editor in chief: Rudolf Augstein (19 November 1952). "WIDERSTAND ....verurteilt worden: Werner Tocha, 20, zu 9 Jahren Gefängnis, Gerhard Blume, 20, zu 8 Jahren Gefängnis, Gerhard Schultz, 20, zu 5 Jahren, Johann Burianek, Todesstrafe, Wolfgang Kaiser, Todesstrafe". Der Spiegel (online). Retrieved 27 October 2014.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ a b c d e f g Gerhard Finn: Nichtstun ist Mord. Die Kampfgruppe gegen Unmenschlichkeit - KgU, Westkreuz-Verlag, Bad Münstereifel 2000, ISBN 3929592541

- ^ a b c d e f g Kai-Uwe Merz: Kalter Krieg als antikommunistischer Widerstand. Die Kampfgruppe gegen Unmenschlichkeit 1948-1959 (=Studien zur Zeitgeschichte, Band 34), Oldenbourg, München 1987

- ^ „...den Frieden der Welt gefährdet und Sabotage und Diversionshandlungen durchgeführt zu haben, indem er als Agent der Ildebrandt'schen [sic!] Terror- und Spionageorganisation Spionageaufträge durchführte und aktiv durch die Herstellung von Sprengstoff, Phosphorampullen, Brandsätze [sic!] usw. für die Durchführung von Sabotageakten tätig war.“

- ^ "Terrorist im Bundesverfassungsgericht?". 19 June 2013.

- ^ "Aus dem Buch "Die Sicherheit".

- ^ Besondere Richtlinien für die Vorbereitung von Schauprozessen hatten im Januar 1952 Generalstaatsanwalt und Justizminister der DDR in einer „Gemeinsamen Rundverfügung“ an die Staatsanwaltschaften und Gerichte bekanntgegeben, teilw. im Wortlaut bei Karl Wilhelm Fricke: Politik und Justiz in der DDR. Zur Geschichte der politischen Verfolgung 1945–1968. Bericht und Dokumentation. Verlag Wissenschaft und Politik, Köln 1979, ISBN 3-8046-8568-4, S. 273f.

- ^ ... er werde „auf Todesstrafe plädieren“, wenn dieser (Müller) nicht aussage, „was in der Anklage steht“.

- ^ a b Editor in chief: Rudolf Augstein (27 March 2013). "1952: Der KgU-Prozess Der Strafprozess gegen die Angeklagten Joachim Müller, seine Ehefrau Ursula Müller, Kurt Hoppe und Wolfgang Kaiser im August 1952 gilt als einer der großen Schauprozesse der frühen DDR-Geschichte....In dem von Ernst Melsheimer als Generalstaatsanwalt der DDR und Hilde Benjamin als Oberster Richterin geführten Verfahren haben die Verteidiger nur Schmuckrollen". Südwestrundfunk (online SWR2 Archivradio: Die Stasi-Bänder). Retrieved 28 October 2014.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ a b Testimony of defense lawyer Büsing who later escaped from East Berlin to West Berlin and there repeatedly gave statements about the KgU. See also Gerhard Finn: Nichtstun ist Mord. Die Kampfgruppe gegen Unmenschlichkeit - KgU page 130

- ^ Gerhard Finn: Nichtstun ist Mord. Die Kampfgruppe gegen Unmenschlichkeit - KgU, Westkreuz-Verlag, Bad Münstereifel 2000, ISBN 3929592541, Finn bases himself on Stasi archives (page 131) and also cites Merlsheimer's exchanges with the court officers (page 132).

- ^ Karl Wilhelm Fricke, Roger Engelmann: „Konzentrierte Schläge“: Staatssicherheitsaktionen und politische Prozesse, Schriftenreihe des BStU, 11, Page 87

- ^ Rudi Beckert: Die erste und letzte Instanz. Schau- und Geheimprozesse vor dem Obersten Gericht der DDR. Keip Verlag, Goldbach 1995, ISBN 3-8051-0243-7, S. 249f.

- ^ Gerhard Finn: Nichtstun ist Mord. Die Kampfgruppe gegen Unmenschlichkeit - KgU, Westkreuz-Verlag, Bad Münstereifel 2000, ISBN 3929592541, (page 134).

- ^ Joachim Müller hat seine Erinnerungen veröffentlicht: Für die Freiheit Berlins. Erinnerungen eines Widerstandskämpfers der ersten Stunde gegen das SED-Regime. Haag und Herchen, Frankfurt am Main 1991, ISBN 3-89228-627-2, zu Kaisers Irrglaube und zur Luxuszelle Page 62f.

- ^ Gerhard Finn: Nichtstun ist Mord. Die Kampfgruppe gegen Unmenschlichkeit - KgU, Westkreuz-Verlag, Bad Münstereifel 2000, ISBN 3929592541, (page 135).

- ^ Gerhard Finn: Nichtstun ist Mord. Die Kampfgruppe gegen Unmenschlichkeit - KgU, Westkreuz-Verlag, Bad Münstereifel 2000, ISBN 3929592541, (page 135 footnote).

- ^ Verlautbarung des Staatssekretärs Eggerath vom 26. Mai in: Hans J. Reichhardt (Bearb.): Berlin. Chronik der Jahre 1951–1954. Heinz Spitzing Verlag, Berlin 1968, S. 373 (= Schriftenreihe zur Berliner Zeitgeschichte. Band 5), auch Hermann Weber: Von der SBZ zur DDR. 1945–1968. Verlag für Literatur und Zeitgeschehen, Hannover 1968, page 69 footnote.

- ^ Rudi Beckert: Die erste und letzte Instanz. Schau- und Geheimprozesse vor dem Obersten Gericht der DDR. Keip Verlag, Goldbach 1995, ISBN 3-8051-0243-7, page 258. "Giftmischer Kaiser" ... "Eisenbahnattentäter Burianek"

- ^ Gerhard Finn: Nichtstun ist Mord. Die Kampfgruppe gegen Unmenschlichkeit - KgU, Westkreuz-Verlag, Bad Münstereifel 2000, ISBN 3929592541, page 50

- ^ Rudi Beckert: Die erste und letzte Instanz. Schau- und Geheimprozesse vor dem Obersten Gericht der DDR. Keip Verlag, Goldbach 1995, ISBN 3-8051-0243-7, page 250

- ^ Gerhard Finn: Nichtstun ist Mord. Die Kampfgruppe gegen Unmenschlichkeit - KgU, Westkreuz-Verlag, Bad Münstereifel 2000, ISBN 3929592541, page 133