Wipeout (video game)

| Wipeout | |

|---|---|

European PlayStation cover art | |

| Developer(s) | Psygnosis[a] |

| Publisher(s) | Psygnosis |

| Director(s) | John White[1] |

| Producer(s) | Dominic Mallinson[1][2] |

| Designer(s) | Nick Burcome[1] |

| Composer(s) | Tim Wright[1] |

| Series | Wipeout |

| Platform(s) | PlayStation, DOS, Microsoft Windows, Sega Saturn |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Racing |

| Mode(s) | Single-player, multiplayer[3][4] |

Wipeout (stylised as wipE′out″) is a 1995 racing video game developed and published by Psygnosis for the PlayStation. The first instalment in the Wipeout series, it was a launch title for the PlayStation in Europe. It was ported to DOS, followed by Sega Saturn the next year. Psygnosis' parent company, Sony Computer Entertainment, re-released the game for the PlayStation 3 and PlayStation Portable via the PlayStation Network in 2007.

Set in 2052, players compete in the F3600 anti-gravity racing league, piloting one of a selection of craft in races on several tracks around the world. Unique at the time, Wipeout was noted for its futuristic setting, weapons designed to slow opponents and its marketing campaign designed by Keith Hopwood and The Designers Republic. The game features original music from CoLD SToRAGE, with tracks by Leftfield, The Chemical Brothers, and Orbital appearing on some versions. The game was critically acclaimed on release; critics praised the game for its originality and its vast "unique techno soundtrack", but was criticised for its in-game physics. It is followed by a sequel, Wipeout 2097/XL, released in 1996. Alongside its successor, it is considered to be one of the greatest video games of all time.

Gameplay

[edit]

Wipeout is a racing game that is set in 2052, where players compete in the F3600 anti-gravity racing league.[5] The game allows the player to pilot one of a selection of craft in races on several different tracks.[6] There are four racing teams to choose from, and two ships for each team. Each ship has its distinct characteristics of acceleration, top speed, mass, and turning radius.[7] By piloting their craft over power-up pads found on the tracks, the player can pick up various weapons and power-ups such as shields, turbo boosts, mines, shock waves, rockets, or missiles. The power-ups allow the player to either protect their craft or disrupt the competitors' craft.[8]

There are seven race tracks in the game, six of them located in futuristic versions of countries such as Canada, the United States and Japan. After all tracks have been completed on the Rapier Championship, a hidden track (Firestar), set on Mars is unlocked.[9] Wipeout features a multiplayer mode using the PlayStation Link Cable, allowing two player to race against each other and the six remaining AI competitors.[3] The game also supports the NeGcon, a third-party controller designed by Namco.[10]

Development and release

[edit]Wipeout was developed and published by Liverpudlian developer Psygnosis (later known as Studio Liverpool), with production starting in the second half of 1994.[2][11] According to Lee Carus, one of the artists, Wipeout took 14 months to develop, and the concept began as a conversation between Nick Burcombe and Jim Bowers at a pub in Oxton, Merseyside. Bowers then started on a concept film which was shown around Psygnosis' offices. It proved popular, and Wipeout was approved and production began.[12] An early demo video was shown at the April 1994 European Computer Trade Show (ECTS).[13] The marketing and artwork were designed by Keith Hopwood and The Designers Republic in Sheffield.[11] Aimed at a fashionable, club-going, music-buying audience, Keith Hopwood and The Designers Republic created art for the packaging, in-game branding, and other promotional materials.[11] A non-playable CGI film mock-up inspired by the game appeared in the teen cult film Hackers (1995), in which both protagonists play the game in a nightclub.[14]

The team was under pressure, as it consisted of around ten people, and they were on a tight schedule. Carus stated that the code had to be rewritten three quarters of the way through development, and that the team was confident that they could complete the game on time.[12] The vehicle designs were based on Matrix Marauders, a 3D grid-based strategy game whose concept was developed by Bowers and released for the Amiga in 1990.[15] Burcombe, the game's future designer, was inspired to create a racing game using the same types of 'anti-gravity' vehicles from SoftImage's animation of two ships racing. The name "Wipeout" was given to the game during a pub conversation, and was inspired by the instrumental song "Wipe Out" by The Surfaris. Designing the tracks proved to be difficult due to the lack of draw distance possible on the system. Players received completely random weapons, resembling Super Mario Kart in their capability to stall rather than destroy opponents.[16] Burcombe said that Wipeout was influenced by Super Mario Kart more than any other game.[12]

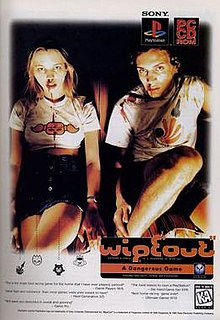

Wipeout gained a significant amount of controversy on its initial release.[17] A marketing campaign created and launched by Keith Hopwood and The Designers Republic included an infamous promotional poster, featuring a bloodstained television and radio presenter Sara Cox, which was accused by some of depicting a drug overdose.[14] Next Generation printed the ad with the blood erased; the magazine staff explained that not only had they been under pressure from newsstand retailers about violent imagery in games magazines, but they themselves felt the blood added nothing to the ad other than shock value.[18] The poster branded Wipeout "a dangerous game", with Wipeout's lead artist Neil Thompson suggesting—and designer Nick Burcome denying—that the "E" in Wipeout stood for ecstasy.[14]

Wipeout was first released alongside the PlayStation in Europe on 29 September 1995.[19] It was the PlayStation's best-selling launch title in Europe.[20] The game was released in the United States in November. The game went to number one in all the format charts, with over 1.5 million units of the franchise having been sold to date throughout Europe and North America.[21] Wipeout was ported to the Sega Saturn in 1996 by Tantalus Entertainment. Because the company behind the PlayStation, Sony, owned the applicable rights to the last three tracks of the PlayStation version's soundtrack, new music was added for the Saturn version by Rob Lord and Mark Bandola.[22][23] The Sega Saturn version was released by Sega in North America, despite being a direct competitor of Sony.

Music

[edit]The development of Wipeout placed a strong emphasis on its music, which was a key component of the game’s identity. Designer Nick Burcombe recounted how playing Super Mario Kart while listening to heavy techno music inspired the idea of creating a game with high-speed, hovering ships racing through futuristic tracks set to a driving electronic soundtrack.[14] For the game's concept demo movie, the team selected the big beat band The Prodigy's track "No Good (Start the Dance)," with Psygnosis artist Jim Bowers noting that the song was chosen “because of the pace of it really fitting with the action on screen.”[24]

Composer Tim Wright, also known as CoLD SToRAGE, was brought on to create the game’s music but initially struggled to adapt his synth-pop background to the "future UK" sound of big beat and techno envisioned by the team.[25] This style, characterised by heavy loops and basslines, breakbeats, big beats, and dramatic builds and drops, was key to evoking the energy of rave culture. To craft this sound, Wright used sample CDs popular among top producers of the time and synthesisers like the Roland JD-800 to produce the heavy, distorted beats and sounds that characterised the game's soundtrack.[26] Team members also took him to nightclubs to immerse him in the environment that inspired the game’s aesthetic.[25]

Despite initial reluctance from record companies to work with the gaming industry,[12] Wipeout’s PlayStation version featured music from notable electronic artists including Leftfield, The Chemical Brothers, and Orbital. Burcombe had hoped to commission The Prodigy to compose an original track for the game, but they declined to participate.[26] Instead, Orbital contributed "Wipeout (P.E.T.R.O.L)." These tracks, combined with the game’s visual style, became a central feature and enhanced its appeal to a young, club-going audience.[27]

The game’s advertising reinforced this connection to club culture, depicting players continuing the party atmosphere at home with Wipeout and positioning it as the “afterparty” game.[26][28]

| No. | Title | Performer | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Data Track" | No Artist | |

| 2. | "Cairodrome" | CoLD SToRAGE | 5:15 |

| 3. | "Cardinal Dancer" | CoLD SToRAGE | 5:22 |

| 4. | "Cold Comfort" | CoLD SToRAGE | 5:05 |

| 5. | "DOH-T" | CoLD SToRAGE | 5:15 |

| 6. | "Messij" | CoLD SToRAGE | 5:16 |

| 7. | "Operatique" | CoLD SToRAGE | 5:18 |

| 8. | "Tentative" | CoLD SToRAGE | 5:26 |

| 9. | "Transvaal" | CoLD SToRAGE | 5:07 |

| 10. | "Afro Ride" | Leftfield | 6:26 |

| 11. | "Chemical Beats" | The Chemical Brothers | 4:52 |

| 12. | "Wipeout (P.E.T.R.O.L)" | Orbital | 6:15 |

| No. | Title | Performer | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Data Track" | No Artist | |

| 2. | "Cairodrome" | CoLD SToRAGE | 5:15 |

| 3. | "Cardinal Dancer" | CoLD SToRAGE | 5:22 |

| 4. | "Cold Comfort" | CoLD SToRAGE | 5:05 |

| 5. | "DOH-T" | CoLD SToRAGE | 5:15 |

| 6. | "Messij" | CoLD SToRAGE | 5:16 |

| 7. | "Operatique" | CoLD SToRAGE | 5:18 |

| 8. | "Tentative" | CoLD SToRAGE | 5:26 |

| 9. | "Transvaal" | CoLD SToRAGE | 5:07 |

| No. | Title | Performer | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Data Track" | No Artist | |

| 2. | "Cairodrome" | CoLD SToRAGE | 5:15 |

| 3. | "Cardinal Dancer" | CoLD SToRAGE | 5:22 |

| 4. | "Cold Comfort" | CoLD SToRAGE | 5:05 |

| 5. | "DOH-T" | CoLD SToRAGE | 5:15 |

| 6. | "Messij" | CoLD SToRAGE | 5:16 |

| 7. | "Operatique" | CoLD SToRAGE | 5:18 |

| 8. | "Tentative" | CoLD SToRAGE | 5:26 |

| 9. | "Transvaal" | CoLD SToRAGE | 5:07 |

| 10. | "Brickbat" | Rob Lord & Mark Bandola | 5:59 |

| 11. | "Planet 9" | Rob Lord & Mark Bandola | 4:43 |

| 12. | "Poison" | Rob Lord & Mark Bandola | 5:18 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Performer | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Afro Ride" (Afro-Left, 1995) | Neil Barnes, Paul Daley, Neil Cole | Leftfield | 4:24 |

| 2. | "Chemical Beats" (from Exit Planet Dust, 1995) | Tom Rowlands, Ed Simons | Chemical Brothers | 4:50 |

| 3. | "Blue Monday (Hardfloor Mix)" (from Blue Monday-95, 1995) | Bernard Sumner, Peter Hook, Stephen Morris, Gillian Gilbert | New Order | 8:34 |

| 4. | "The Age of Love (Jam & Spoon Mix)" | Bruno Sanchioni, Giuseppe Cherchia | Age of Love | 6:45 |

| 5. | "Wipeout (P.E.T.R.O.L)" (from In Sides, 1996) | P & P Hartnoll | Orbital | 6:15 |

| 6. | "One Love (Edit)" (from Music for the Jilted Generation, 1994) | Liam Howlett | The Prodigy | 3:53 |

| 7. | "La Tristesse Durera (Scream to a Sigh) (Dust Brothers Mix)" (from Gold Against the Soul, 1993) | Nicky Wire, Richey James | Manic Street Preachers | 6:13 |

| 8. | "When (K-Klass Pharmacy Mix)" | Lucia Holm, Paul Carnell | Sunscreem | 8:39 |

| 9. | "Good Enough (Geminis Psychosis Mix)" | L. Cittadini, M. Braghieri | B.B. feat Angie Brown | 8:54 |

| 10. | "Circus Bells (Hardfloor Remix)" | R. Armani | Robert Armani | 8:58 |

| 11. | "Captain Dread" (from Second Light, 1995) | G. Roberts, Irvine, McGlynn | Dreadzone | 5:24 |

| 12. | "Transamazonia (Deep Dish Rockit Express Dub Mix)" | Colin Angus, Richard West | The Shamen | 4:21 |

Reception

[edit]| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| AllGame | |

| Computer and Video Games | 96% (PS1)[29] |

| Edge | |

| Electronic Gaming Monthly | 7.125/10 (SAT)[31] |

| Famitsu | 30/40 (PS1)[39] 31/40 (SAT)[40] |

| IGN | 8/10 (PS1)[32] |

| Next Generation | |

| Maximum | |

| CD Player | 8/10 (PS1)[38] |

Upon release, the game was critically acclaimed. IGN staff praised the game for its originality and unique techno soundtrack, but criticised the difficulty with manoeuvring the vehicles and also the difficulty of the game itself, stating that "there aren't nearly enough competitors" and that the player would have "[pulled] ahead of the other racers with no problem".[32] Edge cited that it was hard to criticise "such a beautifully realised and well-produced game which [exploited] the PlayStation's power so well", but did show similar concerns over the game's longevity regarding its "reliance on track-based power-ups" that would "limit Wipeout's lifespan" in comparison to Super Mario Kart.[30] GamePro gave the PlayStation version a rave review, predicting that "Wipeout's taut action and grueling courses will lure many diehard racing fans to this new system." They particularly praised the challenging gameplay and precise controls. They said the fact that multiplayer is only through the PlayStation Link Cable is the game's one major flaw, since the PlayStation still had a low installed base at this point and thus this would not be an option for most players.[41] A reviewer for Next Generation applauded the stylish and detailed visuals, the "heart-pounding soundtrack", and particularly the exhilarating feel of the racing. He commented that the controls have a potentially frustrating learning curve but are worth mastering, and deemed the game "A new high-water mark".[33] Maximum opined that of all the games in the PlayStation's European launch line-up, "not one title can match up to the awesome nature of Psygnosis' WipeOut. It's an amazing spectacle to behold, it sounds absolutely fantastic and it's the best playing racing game yet beheld on a next generation super console." Making particular note of the lack of pop-up, the coherent style and concept, the soundtrack, the unlockable Rapier mode, and the PAL optimisation,[35] they gave it their "Maximum Game of the Month" award.[42]

The later Saturn version also received generally positive reviews, though most critics agreed that it was inferior to the PlayStation version. In Sega Saturn Magazine, Rad Automatic praised the large number of tracks and the distinctive flavour of each one, and remarked that the gameplay is very easy to get into but provides more than enough challenge. He criticised it as not being as good as the PlayStation version, though he noted that none of the shortcomings impact the gameplay.[43] The four reviewers from Electronic Gaming Monthly similarly praised the number and variety of tracks along with the strong challenge the game presented, and were much more approving of the graphics than Sega Saturn Magazine, describing them as "vibrant" and "gorgeous".[31] A Next Generation critic said that while the graphics are slightly less sharp and the controls feel different, the Saturn version is essentially the same game as the PlayStation version.[34] Both Air Hendrix of GamePro and a reviewer for Maximum argued that the Saturn version is noticeably not as polished as the PlayStation version but still excellent in absolute terms, making it a pointless purchase for PlayStation owners but recommended for Saturn-only players.[44][36] In 1996, GamesMaster ranked the PlayStation version 41st on their "Top 100 Games of All Time."[45]

Legacy

[edit]The game's initial success led to Psygnosis developing several sequels which would later become part of the Wipeout franchise. A direct sequel, Wipeout 2097, was released for the PlayStation and Sega Saturn in 1996, which was met with positive reviews, especially aimed towards the vastly improved game engine and new physics the game offered.[16] A Nintendo 64 spin-off, Wipeout 64, was released in 1998 and was met with considerable praise from critics, but was noted to be too similar to the original Wipeout.[46]

Wipeout has been described as being synonymous with Sony's debut gaming hardware and as an early showcase for 3D graphics in console gaming.[2] It has since been re-released as a downloadable game for the PlayStation 3 and PlayStation Portable via the PlayStation Network in 2007,[47][48] and then in 2011 on Xperia Play via the PlayStation Pocket service.[49][50]

The game's soundtrack and musical sensibility is credited with exposing millions to underground club and rave music and inaugurating a new era of music in video games.[14][51] In 2021, Mat Ombler wrote that the game "brought the nightclub experience into bedrooms and living rooms across the globe."[52] Writer Adam Ismail described Wipeout as a "cultural force," a game "where the music and visual style were as crucial—if not, arguably more so—than the physical experience of actually playing it."[53] In 2023, CoLD SToRAGE's soundtrack was remastered, rereleased, and pressed onto vinyl for the first time, with added remixes from contemporary electronic artists such as Kode9 and μ-Ziq.[54] The soundtrack, especially its use of tracks by popular contemporary artists, has been credited with prompting gaming developers to allot greater importance to the music in their games.[55]

Wipeout's visual identity, graphic design, logos, and typography made by The Designers Republic have been credited as a significant achievement in both game and design history.[56][57][58][59] In 2016, game journalist Luke Plunkett wrote "the visual influence the game has had is staggering" and "its bright, neo-Tokyo style still being admired today (you can see echoes of it in everything from Mass Effect to Mario Kart 8 to Destiny)."[60] In 2023, an art book entitled WipEout: Futurism was announced to be published in 2024, focused on commemorating the game's artistic and graphic style.[61][62]

The source code for the PlayStation and the Windows versions of the game was leaked on 27 March, 2022 by the video game preservation group Forest of Illusion.[63][64][65] Based on this leaked code, there were two source ports by enthusiasts: WipeOut Phantom Edition for Microsoft Windows, which is closed source[66] and wipEout Rewrite for Windows, macOS, Linux and WebAssembly by Dominic Szablewski, which is source-available.[67][68][69][70]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Ported to Sega Saturn by Tantalus Entertainment

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Fairclough, Damien; Burcombe, Nick (1995). "Credits". WipEout Manual (instruction manual). Psygnosis. p. 21. SCES-00010.

- ^ a b c Leadbetter, Richard (4 December 2014). "20 years of PlayStation: the making of WipEout". Eurogamer. Gamer Network. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- ^ a b Fairclough, Damien; Burcombe, Nick (1995). "WipEout with Two Players". WipEout Manual (instruction manual). Psygnosis. p. 18. SCES-00010.

- ^ Turunen, J. "Ruikkuralli". Pelit (in Finnish) (1/1996). Sanoma: 30.

- ^ Fairclough, Damien; Burcombe, Nick (1995). "Are You Ready?". WipEout Manual (instruction manual). Psygnosis. p. 1. SCES-00010.

- ^ Fairclough, Damien; Burcombe, Nick (1995). "Championship/Single Race/Time Trial Selection". WipEout Manual (instruction manual). Psygnosis. p. 8. SCES-00010.

- ^ Fairclough, Damien; Burcombe, Nick (1995). "Team Selection". WipEout Manual (instruction manual). Psygnosis. pp. 9–11. SCES-00010.

- ^ Fairclough, Damien; Burcombe, Nick (1995). "Weapons and Power-Ups". WipEout Manual (instruction manual). Psygnosis. pp. 19–20. SCES-00010.

- ^ "Retro Corner: 'WipEout'". Digital Spy. 18 February 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ^ Fairclough, Damien; Burcombe, Nick (1995). "Options". WipEout Manual (instruction manual). Psygnosis. pp. 6–7. SCES-00010.

wipEout is fully compatible with Namco's NeGcon which will be automatically detected when you insert the NeGcon into controller port number 1.

- ^ a b c "The Designers Republic (Company)". Giant Bomb. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ^ a b c d "The Making Of: Wipeout". Retro Gamer. No. 35. Bournemouth: Imagine Publishing. pp. 78–81. ISSN 1742-3155.

- ^ "Sony PS/X im Anflug" (PDF). PlayTime (in German). 1994. p. 21.

- ^ a b c d e Yin-Pool, Wesley (2013). "WipEout: The rise and fall of Sony Studio Liverpool". Eurogamer. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ Langshaw, Mark (18 February 2012). "Retro Corner: 'WipEout'". Digital Spy. Retrieved 2 September 2014.

- ^ a b Edge staff writers (24 February 2013). "The Making Of: Wipeout". Edge. Future plc. Archived from the original on 10 May 2013. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ^ Clifford-Marsh, Elizabeth. "Sony pulls controversial in-game ads after player protests". marketingmagazine. Band Republic Group. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ "Letters". Next Generation. No. 17. Imagine Media. May 1996. p. 123.

- ^ Leys, Alex (29 September 1995). "Wipeout". Derby Evening Telegraph. p. 16. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

Out: September 29

- ^ Hickman, Sam (March 1996). "The Thrill of the Chase!". Sega Saturn Magazine. No. 5. Emap International Limited. p. 36.

- ^ "PlayStation Sales Showdown – Wipeout". IGN UK. 28 July 2010. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ^ Hickman, Sam (March 1996). "The Thrill of the Chase!". Sega Saturn Magazine. No. 5. Emap International Limited. p. 43.

Although acts such as the Chemical Brothers and Leftfield appear on the Playstation version, Psygnosis have their own in-house music team to create the music for WipEout, but these aren't your usual plinkety music guys.

- ^ Genthe, Kris (10 August 2009). "Review: WipEout (Saturn)".

Psygnosis tweaked things a bit, and added music tracks from Rob Lord & Mark Bandola.

- ^ Dylan Wray, Daniel (2 April 2024). "Wipeout: The Story of the World's First Rave-Inspired Video Game". Mixmag. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ a b "Playstation Classics: The People Behind the Music – Part 2: Tim Wright". Wave. 1 April 2014. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- ^ a b c Noclip - Video Game Documentaries (11 June 2024). Wipeout 2097: The Making of an Iconic PlayStation Soundtrack - Noclip Documentary. Retrieved 5 December 2024 – via YouTube.

- ^ Levin, Harry (22 November 2023). "The Rave & Video Game Legacy of CoLD SToRAGE's wipE'out" Soundtrack". Beatportal. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- ^ H.J., Jordan (10 October 2021). "The Controversial WipEout Poster". Voletic. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- ^ "The Computer and Video Games Christmas Buyers Guide". Computer and Video Games. No. 170 (January 1996). EMAP. 10 December 1995. pp. 8–9.

- ^ a b "Wipeout Review – Edge Online". Edge Online. Edge UK. 24 August 1995. Archived from the original on 21 June 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ^ a b "Review Crew: Wipeout". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 84. Ziff Davis. July 1996. p. 35.

- ^ a b "Wipeout review". IGN. 26 November 1996. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ^ a b "Classic". Next Generation (11). Imagine Media: 169. November 1995.

- ^ a b "A Close Call". Next Generation. No. 19. Imagine Media. July 1996. p. 78.

- ^ a b "Maximum Reviews: Wipeout". Maximum: The Video Game Magazine (1). Emap International Limited: 148–9. October 1995.

- ^ a b "Maximum Reviews: Wipeout". Maximum: The Video Game Magazine (5). Emap International Limited: 148. April 1996.

- ^ "Wipeout - Review". Allgame. Archived from the original on 15 November 2014.

- ^ "Wipeout Review". CD Player (in German). January 1996. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20130627175348/https://www.famitsu.com/cominy/?m=pc&a=page_h_title&title_id=11827

- ^ "セガサターンレースゲーム一覧".

- ^ "ProReview: Wipeout". GamePro. No. 86. IDG. November 1995. p. 52.

- ^ "The Essential Buyers Guide". Maximum: The Video Game Magazine (1). Emap International Limited: 141. October 1995.

- ^ Automatic, Rad (April 1996). "Review: Wipeout". Sega Saturn Magazine (6). Emap International Limited: 70–71.

- ^ "ProReview: Wipeout". GamePro. No. 94. IDG. July 1996. p. 68.

- ^ "Top 100 Games of All Time" (PDF). GamesMaster (44): 76. July 1996.

- ^ "Wipeout 64 overview and ranking". Nintendojo. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ Black, Jared (10 March 2007). "News – WipEout Races to PSP via PS3". VGGen. Archived from the original on 28 October 2009. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ "PS Store Release Dates Confirmation". Three Speech: Semi-Official PlayStation Blog. 15 June 2007. Archived from the original on 3 May 2014. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ Silversides, Nick (13 July 2011). "WipEout Now Available On The Xperia PLAY". The Average Gamer. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

- ^ McFerran, Damien (14 July 2011). "WipEout". Pocket Gamer. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- ^ Levin, Harry (22 November 2023). "The Rave & Video Game Legacy of CoLD SToRAGE's wipE'out" Soundtrack". Beatportal. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ Ombler, Mat (29 September 2021). "'Tony Hawk's Pro Skater' Exposed Millions to Punk. 'Wipeout' Did the Same for Rave". Vice Magazine. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ Ismail, Adam (15 August 2023). "Wipeout, the Coolest Racing Game of the '90s, Is Playable in Your Browser Right Now: Wipeout wasn't just a racing game—it was a cultural landmark for cutting edge art and music". The Drive. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ Jarman, Casey (21 November 2023). "How CoLD SToRAGE's "Wipeout" Score Steered Video Game Music Into the Millennium". Bandcamp Daily. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ "The Future Sound of Game Music". Next Generation. No. 24. Imagine Media. December 1996. p. 85.

Videogames and contemporary music have now officially met, shaken hands, and declared their respect for each other. This is good news for gamers as, post-Wipeout, developers have finally realized that the right music can be used to enrich the gaming experience.

- ^ Morley, Pete (19 June 2018). "On how the Designers Republic sculpted childhoods". Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ Smith, Graham (18 January 2023). "WipEout Logo History 1995-2017, Making of the Wipeout Logo Design Plus Various In-game Graphics by Designers Republic and Fans". Smithographic. The Logo Smith. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ Tucker, Emma (11 June 2019). "An oral history of Wipeout". Creative Review. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ Plunkett, Luke (23 April 2019). "The Making Of Wipeout's Logo, An All-Time Classic". Kotaku. Archived from the original on 23 April 2019. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ Plunkett, Luke (14 July 2016). "WipeOut Was One Of The Coolest Games Ever Made". Kotaku. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ Plunkett, Luke (22 November 2023). "New Book Reminds Us That WipeOut Remains The Coolest Video Game Ever Released". Aftermath. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ Gardner, Matt (21 November 2023). "'WipEout: Futurism' Promises Perfect Book For Pioneering Racing Game". Forbes. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ Murray, Sean (22 March 2022). "Source Code For The Original Wipeout Released". TheGamer. Valnet Inc. Archived from the original on 28 March 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ Wright, Steven (29 March 2022). "PlayStation classic Wipeout source code released by archivists". Input. Bustle Digital Group. Archived from the original on 25 August 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ Banerjee, Sampad (30 March 2022). "Original PS1 WipEout's Source Code Released Online by Game Preservationists". GamingBolt. Archived from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ Jarvis, Matt (17 July 2023). "WipeOut Phantom Edition finally gives the PlayStation racing classic the PC remaster it deserves, thanks to one fan". Rock, Paper, Shotgun. Gamer Network. Archived from the original on 20 July 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ Purdy, Kevin (24 August 2023). "Leaked Wipeout source code leads to near-total rewrite and remaster". Ars Technica. Condé Nast. Archived from the original on 25 August 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ Middler, Jordan (10 August 2023). "A new fan-made port of Wipeout can be played in a web browser". Video Games Chronicle. Gamer Network. Archived from the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ Dinsdale, Ryan (11 August 2023). "Wipeout Fan Ports Classic Game to PC, Tells PlayStation to Shut It Down and Make a Real Remaster". IGN. Ziff Davis. Archived from the original on 14 August 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ Gach, Ethan (11 August 2023). "Fan Ports PlayStation Classic, Dares Sony To Shut Him Down And Make Its Own". Kotaku. G/O Media. Archived from the original on 19 August 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

External links

[edit]- Video game

- Soundtrack

- 1995 video games

- Advertising and marketing controversies

- DOS games

- Multiplayer and single-player video games

- PlayStation (console) games

- Racing video games

- Sega video games

- Sega Saturn games

- Video games scored by Tim Wright (Welsh musician)

- Video games developed in the United Kingdom

- Video games set in the 2050s

- Video games set in Canada

- Video games set in Greenland

- Video games set in Japan

- Video games set in Russia

- Video games set in the future

- Video games set in the United States

- Video games set on Mars

- Windows games

- Wipeout (video game series)

- Psygnosis games