Whiz Kids (baseball)

The Whiz Kids is the nickname of the 1950 Philadelphia Phillies of Major League Baseball.[1] The team had a number of young players: the average age of a member of the Whiz Kids was 26.4.[2] The team won the 1950 National League pennant but failed to win the World Series.

After owner R. R. M. Carpenter, Jr. built a team of bonus babies, the 1950 team won for the majority of the season, but slumped late, allowing the defending National League champion Brooklyn Dodgers to gain ground in the last two weeks. The final series of the season was against Brooklyn, and the final game pitted the Opening Day starting pitchers, right-handers Robin Roberts and Don Newcombe, against one another. The Phillies defeated the Dodgers in extra innings in the final game of the season on a three-run home run by Dick Sisler in the top of the tenth inning. In the World Series which followed, the Whiz Kids were swept by the New York Yankees, who won their second of five consecutive World Series championships.[3]

The failure of the Whiz Kids to win another pennant after their lone successful season has been attributed to multiple theories, the most prominent of which is Carpenter's unwillingness to integrate his team after winning a pennant with an all-white team.

Before 1950

[edit]

Prior to 1950, the Philadelphia Phillies had made just one appearance in the World Series, which occurred in 1915. In that series, they were defeated by the Boston Red Sox in five games.[4] From 1933 to 1948, the Phillies posted sixteen consecutive losing seasons, a record for the 20th century and a major league record that stood until 2009 (broken by the Pittsburgh Pirates).[5]

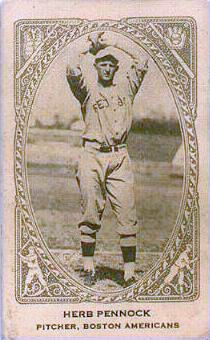

Ben Chapman, who managed the Phillies from 1945 to 1948,[6] bemoaned the loss of general manager Herb Pennock, who died during Chapman's final season. Bob Carpenter, the new owner of the team, replaced Chapman after his comments to media sources that Pennock needed to be replaced with "another strong baseball man".[7] The new manager, Eddie Sawyer, arrived in the 1948 season and led the Phillies to a winning record in 1949 (81–73).[8] Carpenter's team-building approach was built on provision of ample bonuses for players. Signing bonuses for the players on the 1950 squad ranged from $3,000 ($37,992 in present-day dollars) to $65,000 ($823,154 present-day).[7]

The Dodgers, meanwhile, had appeared in the 1947 and 1949 World Series, losing to the New York Yankees in both. Indeed, the Phillies' appearance against the Yankees in the 1950 World Series was the only time in the Yankees' run of five consecutive championships (1949–1953) wherein they did not face one of the other teams from New York City (the Dodgers or the New York Giants).[9]

The 1950 season

[edit]April–May

[edit]The Phillies opened the season with a 9–1 defeat of the Dodgers on April 18. The starters in the game were Robin Roberts for Philadelphia and Don Newcombe, Brooklyn's 17-game winner from the prior season. After a split with the Dodgers, the Phillies played four games against the Boston Braves, losing two, tying one, and winning one; reliever Jim Konstanty earned his first win in the final game of the series. Three games in New York against the Giants and the Dodgers did not improve the team's record, but they took three of the next four from Boston. In May, the team amassed its longest winning streak of the season, when they won six consecutive games—one against the St. Louis Cardinals, a three-game sweep of the Cincinnati Redlegs, one against the Pittsburgh Pirates, and the last against the Giants. Konstanty earned another win against New York as the Phillies took two wins from the three-game set, and the end of the Phillies' May was strong with a five-game winning streak against Pittsburgh and the Giants. Two doubleheaders against New York and Brooklyn resulted in three losses to finish the month.[10]

June–July

[edit]

In the middle months of the season, the Whiz Kids played strongly, notching winning records of 14–11 in June and 21–13 in July.[10] Early in July, the Phillies put together a four-game winning streak against the two National League teams from New York, sweeping the Giants in a two-game set and taking two of three from Brooklyn.[11] The 1950 All-Star Game was played on July 11, with four Phillies selected to the roster. Willie Jones started at third base and led off the game, while Roberts was selected as the starting pitcher. Konstanty and Dick Sisler were named to the team as reserves out of the bullpen and in the outfield, respectively.[12] The Phillies played twelve doubleheaders in June and July, including three sets on consecutive game days (July 16 and 18 against the Chicago Cubs and July 19 against Pittsburgh).[11]

August–September: Pennant race

[edit]August was the Whiz Kids' strongest month, with a 20–8 record and a .714 winning percentage. During August and September, the Phillies put together two five-game winning streaks and a four-game winning streak as well.[2] By September 20, the Phillies had a 7+1⁄2-game lead over Boston and a nine-game lead on Brooklyn.[13] However, injuries began to mount, and with injuries came losses—of players and of games. Among the casualties were pitcher Bob Miller, who injured his back slipping on wet stairs; outfielder Bill Nicholson, diagnosed with diabetes, was out for the remainder of the season.[14] In the last week of the season, with their lead over the Dodgers at four games, the Phillies dropped back-to-back doubleheaders to the Giants, and lost the next game to Brooklyn to fall into their longest losing slump of the season and set up the final game of the season at Ebbets Field.[14] Another loss to the Dodgers would force a best-of-three playoff for the National League pennant.[15]

Final game against Brooklyn

[edit]

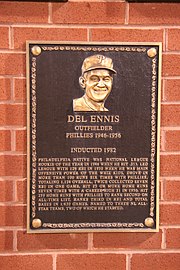

No one in the Phillies clubhouse knew who would pitch the final game of the season against the Brooklyn Dodgers, except Sawyer, until an hour before the game, when the manager handed Roberts the ball.[16] Opposing Roberts was Newcombe, who had opened the season against the Phillies in their 9–1 victory. Roberts walked a batter in the bottom of the first inning, but no other runners reached base for Brooklyn until the fourth inning. The Phillies had four baserunners on three singles and a walk against Newcombe, but no one advanced beyond first base. In the bottom of the fourth, Pee Wee Reese hit a double for the Dodgers, but Roberts retired the next three batters in order.[16] In the sixth inning, Sisler was on base, having hit a single through the gap into right field between first baseman Gil Hodges and second baseman Jackie Robinson.[17] Jones singled to left field, driving him in for the first run of the game;[18] his hit has been called "the most important in Phillies history to that point".[19] The Dodgers tied the game on a home run by Reese in the bottom of the sixth; the ball landed on a ledge in right-center field and, caught by a wire screen along the foul line, stayed in play but out of Del Ennis' reach.[17][18]

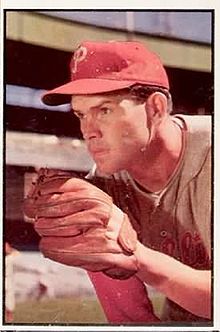

The Phillies got men on base in the seventh, eighth, and ninth innings, while Roberts allowed a single to Dodgers catcher Roy Campanella in the eighth, but the score remained tied, 1–1.[17] In the bottom of the ninth inning, Roberts walked Cal Abrams,[17] who advanced to second on a single by Reese[20] and came around to home plate on Duke Snider's hard single up the middle.[21] Richie Ashburn threw the ball to catcher Stan Lopata, who had replaced starting catcher Andy Seminick on defense in the bottom of the 9th inning [22] from his position in center field, and Lopata tagged Abrams out at the plate.[23] With runners now on second and third, Roberts walked Robinson intentionally to load the bases, then induced Carl Furillo to foul out to Eddie Waitkus.[23] After Roberts retired the last batter, the game went to extra innings. Newcombe allowed hits to Roberts and Waitkus, who advanced to second and third when Ashburn sacrificed himself.[20] Sisler came to the plate and hit a high outside fastball from Newcombe over the left-field wall, dancing to first base as he watched it fly out.[21] Comfortable on the mound again with a 4–1 lead, Roberts retired the side in the tenth inning to secure the complete-game victory and the Phillies' second pennant in franchise history.[20]

World Series

[edit]Sawyer turned heads around the league by naming Konstanty, his closer, the starter for Game 1;[20] he had few options without Robin Roberts, who had started four games in eight days,[14][24] rookie Bubba Church, who had been hit in the eye with a line drive,[25] and Curt Simmons, who was activated into military service on September 10.[14] Konstanty lost the game, though he allowed only one run on five hits in eight innings pitched; Yankees starter Vic Raschi pitched a complete-game shutout, striking out five.[26]

Roberts returned to the mound to face Allie Reynolds in the second game, but one run scored could not win the game for the Phillies, as Joe DiMaggio hit a home run to lead off the top of the tenth inning to put the Yankees ahead in the game 2–1, and in the series 2–0.[27] With Ken Heintzelman on the mound in Game 3, the Phillies outhit the Yankees, but could not push enough runs across the plate. The Whiz Kids lost, 3–2.[18] Miller was the Phillies' last hope for a victory, but the ailing rookie was no match for 21-year-old Whitey Ford,[18] as the Phillies lost the last game, 5–2,[28] and became the first team swept in the World Series since the 1939 Cincinnati Reds.[29]

Records and legacy

[edit]Konstanty became the second Phillie to win the Most Valuable Player Award, after Chuck Klein (1932);[30] his 22 saves and 16 wins by a reliever were both National League records at the time.[31][32] Ennis led the team in batting average, home runs, and runs batted in,[33] while Roberts' 20 wins in 1950 were the beginning of six consecutive seasons with 20 or more wins for the pitcher.[34]

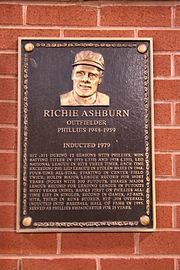

As the catcher, Seminick provided veteran leadership for the team and helped guide the young pitching staff. Roberts said of Seminick, "If you had to pick a guy in the clubhouse who was our leader that year, it would be Andy. He always played hard, and that was his best year by far."[35] Six players have since been elected members of the Philadelphia Baseball Wall of Fame: outfielder Ashburn; pitchers Roberts, Konstanty, Simmons; and infielders Hamner and Jones.[36] National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum inductees from the Whiz Kids include Roberts, who entered the Hall in 1976,[37] and Ashburn, elected in 1995.[38]

The "Whiz Kids" name endured for the Phillies franchise into the 1980s, when the 1983 Philadelphia Phillies, a team of veteran players who faced the Baltimore Orioles in the 1983 World Series, were coined the "Wheeze Kids".[39]

Aftermath and integration

[edit]Many thought that the Whiz Kids, with a young core of talented players, would be a force in the league for years to come.[40][41] However, it was not to be, as the team finished with a 73–81 record in 1951. Aside from a second place tie in the infamous "Phold" of 1964, the team did not finish higher than third place again until 1975.[42] Different players on the Phillies attributed the team's decline to multiple factors. Roberts believed that the Phillies were "good, but never quite as good as the teams that beat us".[41] Ashburn, however, had a different opinion:

"We were the last to get any black ball players. We were still pretty good, but they were just getting better."[43]

The Phillies, as the last team in the National League to integrate, exhibited racist behavior on several occasions. When Jackie Robinson broke the baseball color line in 1947, Chapman instructed his players to spike Robinson and pitch at his head.[44] These activities and attitudes continued through the Whiz Kids era and beyond. Carpenter tended to pass by African-American players; his Whiz Kids had won the pennant while fielding an all-white team, and he, as other owners, tended to pass over any non-white players who did not have superstar-level talent.[43] The Phillies did not integrate until 1957, a decade after Robinson's entry,[44] when John Kennedy made his major league debut on April 22, 1957, at Roosevelt Stadium. Kennedy had two career at bats; the Phillies did not have an African-American regular until 1962, with Ted Savage and Wes Covington. The 1961 regular lineup did include four persons of color with three players from Cuba and one from Mexico, while Covington was a reserve. However, the first African-American star for the Phillies came in 1964 with Dick Allen.

Curt Simmons was the last surviving Whiz Kid, passing away on December 13, 2022.[45]

Roster

[edit]* – Starters, not including pitchers[2]

References

[edit]- Inline citations

- ^ Lassanske, Bob (April 17, 1956). "National League Rich in Baseball Lore". Milwaukee Sentinel. p. 6. Archived from the original on July 20, 2012. Retrieved October 28, 2009.

- ^ a b c "1950 Philadelphia Phillies Batting, Pitching, and Fielding Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Archived from the original on August 4, 2009. Retrieved October 28, 2009.

- ^ Singer, Tom (October 26, 2009). "Yankees stand in Phillies' path to history". Major League Baseball. Archived from the original on October 29, 2009. Retrieved October 29, 2009.

- ^ "1915 World Series (4–1): Boston Red Sox (101–50) over Philadelphia Phillies (90–62)". Baseball-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Archived from the original on October 15, 2008. Retrieved October 28, 2009.

- ^ Kovacevic, Dejan (September 8, 2008). "Pirates reach tragic number with 82nd loss". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on December 16, 2009. Retrieved October 28, 2009.

- ^ "Ben Chapman Managerial Record". Baseball-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Archived from the original on September 9, 2010. Retrieved October 29, 2009.

- ^ a b Marshall, p.365.

- ^ "Eddie Sawyer Managerial Record". Baseball-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Archived from the original on July 29, 2010. Retrieved October 29, 2009.

- ^ "Baseball-Reference Playoff and World Series Index". Baseball-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Archived from the original on January 9, 2010. Retrieved October 28, 2009.

- ^ a b "1950 Philadelphia Phillies Schedule". Baseball-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Archived from the original on September 22, 2010. Retrieved October 29, 2009.

- ^ a b "The 1950 Philadelphia Phillies Regular Season Game Log". Retrosheet, Inc. Archived from the original on January 29, 2016. Retrieved October 29, 2009.

- ^ "All-Star Game Play-By-Play and Box Score". Baseball-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. July 11, 1950. Archived from the original on August 28, 2009. Retrieved October 29, 2009.

- ^ Roberts, pp.8–9.

- ^ a b c d Roberts, p.9.

- ^ Miller, Stuart (2006). The 100 Greatest Days in New York Sports. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 448. ISBN 0-618-57480-8.

phillies 1950 force playoff dodgers.

- ^ a b Roberts, p.10.

- ^ a b c d Roberts, p.11.

- ^ a b c d Kashatus, p.24.

- ^ Blue, p.31.

- ^ a b c d Marshall, p.24.

- ^ a b Blue, p.30.

- ^ "Retrosheet Boxscore: Philadelphia Phillies 4, Brooklyn Dodgers 1". www.retrosheet.org. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2018-12-05.

- ^ a b Roberts, p.12.

- ^ Blue, p.29.

- ^ Lavint, Thomas (October 1989). "Bubba Church: A Forgotten Member of '50 'Whiz Kids'". Baseball Digest. 48 (10). Lakeside Publishing Company: 69–71. ISSN 0005-609X.

- ^ "1950 World Series Game 1". Baseball-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. October 4, 1950. Archived from the original on May 31, 2009. Retrieved October 29, 2009.

- ^ "1950 World Series Game 2". Baseball-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. October 5, 1950. Archived from the original on May 31, 2009. Retrieved October 29, 2009.

- ^ "1950 World Series Game 4". Baseball-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. October 7, 1950. Archived from the original on May 31, 2009. Retrieved October 29, 2009.

- ^ Kashatus, p.25.

- ^ "Most Valuable Player MVP Awards & Cy Young Awards Winners". Baseball-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Archived from the original on January 9, 2010. Retrieved October 28, 2009.

- ^ Gillette, Gary; Gammons, Peter (2007). The ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia. Palmer, Pete. Sterling Publishing Company. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-4027-4771-7.

- ^ Nemec, David; Flatow, Scott (1989). Great Baseball Feats, Facts and Figures (2008 ed.). New York: Penguin Group. p. 290. ISBN 978-0-451-22363-0. Retrieved 2019-09-07.

- ^ "1950 Philadelphia Phillies Batting Statistics". The Baseball Cube. Archived from the original on December 6, 2009. Retrieved October 29, 2009.

- ^ Phillies Media Relations. "The 1950 Philadelphia 'Whiz Kids'". Philadelphia Phillies. Archived from the original on October 7, 2012. Retrieved October 29, 2009.

- ^ Berger, Ralph. "The Baseball Biography Project: Andy Seminick". Society for American Baseball Research. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved February 9, 2010.

- ^ "Phillies Wall of Fame". Phillies.MLB.com. Major League Baseball. Archived from the original on October 30, 2016. Retrieved October 29, 2009.

- ^ "The Hall of Famers: Robin Roberts". National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Archived from the original on August 13, 2009. Retrieved October 29, 2009.

- ^ "The Hall of Famers: Richie Ashburn". National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Archived from the original on October 23, 2009. Retrieved October 29, 2009.

- ^ Hochman, Stan (May 1983). "A Love Triangle: Pete Rose, Joe Morgan, and Baseball". Baseball Digest. 42 (5). Lakeside Publishing Company: 62–64. ISSN 0005-609X.

- ^ Hochman, Stan (July 1972). "Robin Roberts Remembers the 'Whiz Kids'". Baseball Digest. 31 (7). Lakeside Publishing Company: 35–38. ISSN 0005-609X.

- ^ a b Zimniuch, Fran (2005). "Big Leagues, Here I Come". Richie Ashburn Remembered. Sports Publishing LLC. p. 23. ISBN 1-58261-897-6. Retrieved October 29, 2009.

- ^ "Philadelphia Phillies Team History & Encyclopedia". Baseball-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Archived from the original on February 1, 2009. Retrieved October 28, 2009.

- ^ a b Threston, Christopher (2003). The integration of baseball in Philadelphia. McFarland. p. 57. ISBN 0-7864-1423-5. Retrieved October 29, 2009.

- ^ a b Kashatus, p.23.

- ^ "Last of 1950 Phillies Whiz Kids team, P Curt Simmons dies". ESPN. 2022-12-13. Archived from the original on 2023-01-02.

- Bibliography

- Blue, Max (2009). Phillies Journal 1888–2008: History of Baseball Phillies in Prose and Limerick. AEG Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-60860-190-5.

- Kashatus, William (2008). Almost a Dynasty: The Rise and Fall of the 1980 Phillies. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-4036-8.

- Marshall, William (1999). Baseball's pivotal era, 1945–1951. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2041-1.

- Roberts, Robin; Rogers, C. Paul (1996). The Whiz Kids and the 1950 pennant. Temple University Press. ISBN 1-56639-466-X.

External links

[edit]- "Remembering the Whiz Kids", Phillies Nation, July 13, 2006