White-rumped shama

| White-rumped shama | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male | |

| |

| Female | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Muscicapidae |

| Genus: | Copsychus |

| Species: | C. malabaricus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Copsychus malabaricus (Scopoli, 1786)

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Kittacincla macrura | |

The white-rumped shama (Copsychus malabaricus) is a passerine bird in the Old World flycatcher family Muscicapidae. Native to densely vegetated habitats in the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia, its popularity as a cage-bird and songster has led to it being introduced elsewhere. The Larwo shama, the Kangean shama and the Sri Lanka shama were formerly considered to be conspecific with the white-rumped shama.

Taxonomy

[edit]The white-rumped shama was formally described in 1786 by the Austrian naturalist Giovanni Antonio Scopoli under the binomial name Muscicapa malabarica.[3] Scopoli based his account on "Le gobe-mouches à longue queue de Gingi" that had been described in 1782 by the French naturalist Pierre Sonnerat in the second volume of his book Voyage aux Indes orientales et à la Chine. Sonnerat mentioned that the bird was found on the Malabar Coast of India.[4] The type locality is Mahé.[5] The white-rumped shama is now one of 17 species placed in the genus Copsychus that was introduced in 1827 by the German naturalist Johann Georg Wagler.[6]

Nine subspecies are recognised:[6]

- C. m. malabaricus (Scopoli, 1786) – west, south India

- C. m. macrourus (Gmelin, JF, 1789) – Nepal and north India to south China and Indochina including Côn Sơn Island (off south Vietnam)

- C. m. tricolor (Vieillot, 1818) – west Malaysia, Sumatra and east satellites

- C. m. suavis Sclater, PL, 1861 – Borneo (except north)

- C. m. hypolizus (Oberholser, 1912) – island of Simeulue, west coast of Sumatra. Extinct in the wild

- C. m. opisthochrus (Oberholser, 1912) – Lasia and Babi Islands, west coast of Sumatra. Extinct in the wild

- C. m. melanurus (Salvadori, 1887) – west Sumatran islands (west of Sumatra)

- C. m. mirabilis Hoogerwerf, 1962 – Panaitan (west of Java)

- C. m. ngae Wu, MY & Rheindt, 2022 – islands off the west Thai-Malay Peninsula from Yam Yai Island to the Langkawi Archipelago Possibly extinct in the wild.[7]

The Larwo shama (Copsychus omissus, including javanus), the Kangean shama (Copsychus nigricauda) and the Sri Lanka shama (Copsychus leggei) were formerly considered as subspecies. They are now treated as separate species based on the results of a molecular phylogenetic study that was published in 2022.[6][8][9]

Description

[edit]They typically weigh between 28 and 34 g (1.0 and 1.2 oz) and are around 23–28 cm (9–11 in) in length. Males are glossy black with a chestnut belly and white feathers on the rump and outer tail. Females are more greyish-brown, and are typically shorter than males. Both sexes have a black bill and pink feet. Juveniles have a greyish-brown colouration, similar to that of the females, with a blotchy or spotted chest.

Behaviour

[edit]Breeding

[edit]The white-rumped shama is shy and somewhat crepuscular[10] but very territorial. The territories include a male and female during the breeding season with the males defending the territory averaging 0.09 ha in size,[11] but each sex may have different territories when they are not breeding.

In South Asia, they breed from January to September but mainly in April to June laying a clutch of four or five eggs[12] in a nest placed in the hollow of a tree.[10] During courtship, males pursue the female, alight above the female, give a shrill call, and then flick and fan out their tail feathers. This is followed by a rising and falling flight pattern by both sexes. If the male is unsuccessful, the female will threaten the male, gesturing with the mouth open.

The nest is built by the female alone while the male stands guard.[11][13] The nests are mainly made of roots, leaves, ferns, and stems, and incubation lasts between 12 and 15 days and the nestling period averaged 12.4 days. Both adults feed the young although only the female incubates and broods.[11] The eggs are white to light aqua, with variable shades of brown blotching, with dimensions of about 18 and 23 mm (0.7 and 0.9 in).

Feeding

[edit]They feed on insects in the wild but in captivity they may be fed on a diet of boiled, dried legumes with egg yolk and raw meat.[14]

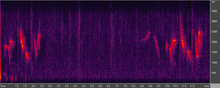

Voice

[edit]

The voice of this species is rich and melodious which makes them popular as cage birds in South Asia with the tradition continuing in parts of Southeast Asia. It is loud and clear, with a variety of phrases, and often mimics other birds. They also make a 'Tck' call in alarm or when foraging.[11] The earliest known recording of bird song was made of an individual of this species in 1889 by Ludwig Koch. Then a child, Koch recorded his pet shama using an Edison wax cylinder.[15][16][17]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]They are native across scrub and secondary forests in South and Southeast Asia, but have been introduced to Kauai, Hawaii, in early 1931 from Malaysia (by Alexander Isenberger), and to Oahu in 1940 (by the Hui Manu Society).[11] Their popularity as a cage bird has led to many escaped birds establishing themselves. They have been introduced to Taiwan where they are considered an invasive species, eating native insect species and showing aggression towards native bird species.[18]

In Asia, their habitat is dense undergrowth especially in bamboo forests.[10] In Hawaii, they are common in valley forests or on the ridges of the southern Koolaus, and tend to nest in undergrowth or low trees of lowland broadleaf forests.[11]

Gallery

[edit]-

Male, Khao Yai National Park, Nakhon Ratchasima, Thailand

-

Male at Durrell Wildlife Park, Jersey

References

[edit]- ^ BirdLife International (2021). "Copsychus malabaricus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T103894856A183077961.en. Retrieved 13 November 2024.

- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2023-03-01.

- ^ Scopoli, Giovanni Antonio (1786). Deliciae florae faunae insubricae, seu Novae, aut minus cognitae species plantarum et animalium quas in Insubica austriaca tam spontaneas, quam exoticas vidit (in Latin). Vol. 2. Ticini [Pavia]: Typographia Reg. & Imp. Monasterii S. Salvatoris. p. 96.

- ^ Sonnerat, Pierre (1782). Voyage aux Indes orientales et à la Chine, fait par ordre du Roi, depuis 1774 jusqu'en 1782 (in French). Vol. 2. Paris: Chez l'Auteur. pp. 196–197.

- ^ Mayr, Ernst; Paynter, Raymond A. Jr, eds. (1964). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 10. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. p. 69.

- ^ a b c Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (August 2024). "Chats, Old World flycatchers". IOC World Bird List Version 14.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 12 November 2024.

- ^ Wu, Meng Yue; Rheindt, Frank E. (2022). "A distinct new subspecies of the white-rumped shama Copsychus malabaricus at imminent risk of extinction". Journal of Ornithology. 163 (3): 659–669. Bibcode:2022JOrni.163..659W. doi:10.1007/s10336-022-01977-2.

- ^ Wu, M.Y.; Lau, C.J.; Ng, E.Y.X.; Baveja, P.; Gwee, C.Y.; Sadanandan, K.; Ferasyi, T.R.; Haminuddin; Ramadhan, R.; Menner, J.K.; Rheindt, F.E. (2022). "Genomes from historic DNA unveil massive hidden extinction and terminal endangerment in a tropical Asian songbird radiation". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 39 (9): msac189. doi:10.1093/molbev/msac189. PMC 9486911. PMID 36124912.

- ^ Clements, J.F.; Rasmussen, P.C.; Schulenberg, T.S.; Iliff, M.J.; Fredericks, T.A.; Gerbracht, J.A.; Lepage, D.; Spencer, A.; Billerman, S.M.; Sullivan, B.L.; Smith, M.; Wood, C.L. (2024). "The eBird/Clements checklist of birds of the world: Updates and Corrections – October 2024". Retrieved 12 November 2024.

- ^ a b c Rasmussen, Pamela C.; Anderton, John C. (2012). Birds of South Asia. The Ripley Guide. Vol. 2: Attributes and Status (2nd ed.). Washington D.C. and Barcelona: Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History and Lynx Edicions. pp. 395–396. ISBN 978-84-96553-87-3.

- ^ a b c d e f Aguon, Celestino Flores & Conant, Sheila (1994). "Breeding biology of the white-rumped Shama on Oahu, Hawaii" (PDF). Wilson Bulletin. 106 (2): 311–328.

- ^ Whistler, H (1949) Popular handbook of Indian birds. Gurney and Jackson. p. 110

- ^ Ali, S. and Ripley, S. D. (1973). Handbook of the birds of India and Pakistan. Vol. 8., Oxford Univ. Press, Bombay, India.

- ^ Jerdon, T. C. (1863) Birds of India. Vol 2. part 1. page 131

- ^ Ranft, Richard (2004) Natural sound archives: past, present and future. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 76(2):456–460 doi:10.1590/S0001-37652004000200041

- ^ "Ludwig Koch on the recording a White-rumped Shama in 1889". BBC, held by British Library. BBC. n.d. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- ^ "Ludwig Koch and the Music of Nature". BBC Archives. BBC. 2009-04-15. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ Bao-Sen Shieh; Ya-Hui Lin; Tsung-Wei Lee; Chia-Chieh Chang & Kuan-Tzou Cheng (2006). "Pet Trade as Sources of Introduced Bird Species in Taiwan" (PDF). Taiwania. 51 (2): 81–86.

External links

[edit]- White-rumped Shama videos, photos & sounds on the Internet Bird Collection

- Male shama songs and mimic of sounds

- Shama song

- Oriental Bird Images: White-rumped Shama (selected images)