West Virginia Penitentiary

| West Virginia Penitentiary | |

|---|---|

The penitentiary | |

| |

| General information | |

| Type | Prison |

| Architectural style | Gothic architecture |

| Location | Moundsville, West Virginia |

| Address | 818 Jefferson Avenue |

| Coordinates | 39°54′59″N 80°44′33″W / 39.91649°N 80.742368°W |

| Current tenants | Moundsville Economic Development Council |

| Construction started | 1866 |

| Completed | 1876 |

| Cost | $363,061 |

| References | |

West Virginia State Penitentiary | |

| Location | 818 Jefferson Ave., Moundsville, West Virginia |

| Area | 19 acres (7.7 ha) |

| Built | 1866 |

| Architectural style | Gothic Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 96000987[1] |

| Added to NRHP | September 19, 1996 |

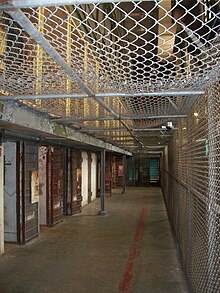

The West Virginia Penitentiary, located in Moundsville, West Virginia is now a withdrawn and retired gothic-style prison that operated from 1866 to 1995. The site is now being maintained as a tourist attraction, museum, training facility, and filming location.[2]

Design

[edit]

The Penitentiary's design is similar to the facility at the 1858 state prison in Joliet, Illinois, with its castellated Gothic, stone structure, complete with turrets and battlements, except it is scaled down to half the size.[3] The original architectural designs have been lost in translation. The dimensions of the West Virginia Penitentiary's parallelogram-shaped prison yard are 82½ feet in length, by 352½ feet in width.[2] The stone walls are 5 feet (1.5 m) thick at the base, tapering to 2½ feet at the top, with foundations 5 feet (1.5 m) deep.[2][3] The center tower section is 682 feet (208 m) long.[2] It lies at the western side of the complex along Jefferson Avenue and is considered the front, as this is where the main entrance is located.[2] The walls here are 24 feet (7.3 m) high and 6 feet (1.8 m) wide at the base, tapering to 18 inches (460 mm) towards the top.[2]

History

[edit]Founding

[edit]In 1863, West Virginia seceded from Virginia at the height of the American Civil War. Consequently, the new state had a shortage of various public institutions, including prisons. From 1863 to 1866, Governor Arthur I. Boreman lobbied the West Virginia Legislature for a state penitentiary but was repeatedly denied. The Legislature at first directed him to send the prisoners to other institutions out of the state, and then they directed him to use existing county jails, both options turned out to be inadequate. After nine inmates escaped in 1865, the local press took up the cause and the Legislature took action.[3] On February 7, 1866, the state Legislature approved the purchase of land in Moundsville for the purpose of constructing a state prison.[3] Ten acres were purchased just outside the then city limits of Moundsville for $3,000.[3] Moundsville proved an attractive site, as it is approximately twelve miles south of Wheeling, West Virginia, which was the state capital at the time.[2][3][4]

The state built a temporary wooden prison nearby that summer. This gave prison officials time to assess what prison design should be used. They had chosen a modified version of the design of Northern Illinois Penitentiary at Joliet, Illinois. Its Gothic Revival architecture "exhibit[ed], as much as possible, great strength and convey[ed] to the mind a cheerless blank indicative of the misery which awaits the unhappy being who enters within its walls."[3]

The first building constructed on the site was the North Wagon Gate.[2] It was made with hand-cut sandstone, which was quarried from a local site.[2] The state used prison labor during the construction process, and work continued on this first phase until 1876.[2] When completed, the total cost of the building was $363,061.[2] In addition to the North Wagon Gate, there was now north and south cellblock areas (both measuring 300 ft. by 52 ft.[3]).[2] South Hall had 224 cells (7 ft. by 4 ft.), and North Hall had a kitchen, dining area, hospital, and chapel,[3] a four-story tower connecting the two was the administration building (measuring 75 ft. by 75 ft.[3]).[2] It included space for female inmates and personal living quarters for the warden and his family.[2][3] The facility officially opened in 1876, and it had a prison population of 251 male inmates, including some who had helped construct the prison where they were incarcerated.[2] After this phase, work began on prison workshops and other secondary facilities.[3][5]

Operation

[edit]In addition to construction, the inmates had other jobs to do in support of the prison. In the early 1900s some industries within the prison walls included a carpentry shop, a paint shop, a wagon shop, a stone yard, a brickyard, a blacksmith, a tailor, a bakery, and a hospital. At the same time, revenue from the prison farm and inmate labor helped the prison financially which meant that it was virtually self-sufficient. A prison coal mine located a mile away, opened in 1921, helped fill some of the prison's energy needs and saved the state an estimated $14,000 a year. Some inmates were allowed to stay at the mine's camp under the supervision of a mine foreman, who was not a prison employee.[2]

Conditions at the prison during the turn of the 20th century were good, according to a warden's report, which stated that, "both the quantity and the quality of all the purchases of material, food and clothing have been very gradually, but steadily, improved, while the discipline has become more nearly perfect and the exaction of labor less stringent." Education was a priority for the inmates during this time and they even regularly attended class. Construction of a school and library was completed in 1900 to help reform and educate inmates.[2]

However, the conditions at the prison worsened through the years, and the facility would be ranked on the United States Department of Justice's Top Ten Most Violent Correctional Facilities list.[4] One of the more infamous locations in the prison, with instances of gambling, fighting, and raping, was a recreation room known as "The Sugar Shack".[4]

A notable inmate in the early 20th century was labor activist Eugene V. Debs, who served time there from April 13 to June 14, 1919 (at which time he was transferred to an Atlanta prison) on charges of violating the Espionage Act of 1917.

In 1929, the state decided to double the size of the penitentiary due to the problem of overcrowding. The 5 x 7-foot (2.1 m) cells were too small to hold three prisoners at a time, but until the expansion, there was no other option. Two prisoners would sleep in the bunks, with the third sleeping on a mattress on the floor.[4] The state used prison labor again to complete this phase of construction in 1959 which had been delayed by a steel shortage during World War II.[2]

In total, thirty-six homicides took place in the prison.[4] One of the more notable ones is the butchering of R.D. Wall, inmate number 44670. On October 8, 1929, after "snitching" on his fellow inmates, he was attacked while heading to the boiler room by three prisoners with dull shivs.[4]

In 1983, convicted multiple murderer Charles Manson requested to be transferred to this prison to be nearer to his family, in which his request was denied.[6]

1979 Prison Break

[edit]On Wednesday, November 7, 1979, fifteen prisoners escaped from the prison. One of the escapees was Ronald Turney Williams, serving time for murdering Sergeant David Lilly of the Beckley Police Department on May 12, 1975. He managed to steal a prison guard's service weapon in the escape, and upon reaching the streets of Moundsville, encountered twenty-three-year-old off-duty West Virginia State Trooper Philip S. Kesner, who was driving past the prison with his wife.[7][8][9][10] Trooper Kesner saw the escapees and attempted to take action against them but the prisoners pulled him from his car and Williams shot him. Trooper Kesner returned fire at the fleeing suspects despite being mortally wounded.[8]

Williams remained at large for eighteen months, sending taunting notes to authorities and making the FBI's Ten Most Wanted List. During that time, he murdered John Bunchek in Scottsdale, Arizona during a robbery and was connected to crimes in Colorado and Pennsylvania. After a shootout with federal agents at the George Washington Hotel in New York City in 1981, he was apprehended and returned to West Virginia to complete several life sentences. Arizona had sought his extradition for his execution, but as of 26 October 2024 he remains in West Virginia custody.[8][9][10][11][12][13]

At the time, Marshall County Sheriff Robert Lightner was very critical about poor police communications during the break. The sheriff's office and local police did not learn about the escape from the state police instead they first heard of it over the police scanner. "It was a good twenty minutes before we knew about the escape. If somebody had notified us, there's a good chance that the sheriff's department and the Moundsville police could have been on the scene while all the prisoners were still on the block." He was also critical of the four-state manhunt that followed, when convicted murderers David Morgan and Ronald T. Williams, along with convicted rapist Harold Gowers, Jr., remained at large. "Communications have been very poor. I think they should keep the local law enforcement officers more informed I have no idea what they're doing, what they've found."[14]

1986 Riot

[edit]January 1, 1986, was the date of the most infamous riot in the history of the penitentiary. The West Virginia Penitentiary was undergoing many changes and problems, and security had become extremely thin in all areas. Since it was a "cons" prison, most of the locks on the cells had been picked and inmates roamed the halls freely. Bad plumbing and insects caused rapid spreading of various diseases and with the prison holding more than 2,000 men crowding was an issue. Another major contribution to the riot's cause was the fact that it was a holiday. Many of the officers had called off work, and prisoners planned to conduct their uprising on this specific day.

At around 5:30 pm, twenty inmates, known as a group called the "Avengers", stormed the mess hall where Captain Glassock and others were on duty. "Within seconds, he (Captain Glassock), five other officers, and a food service worker were tackled and slammed to the floor. Inmates put knives to their throats and handcuffed them with their own handcuffs."[15] Although several hostages were taken throughout the day, none of them were seriously injured. However, over the course of the two-day upheaval, three inmates were killed for an assortment of reasons. "The inmates who initiated the riot were not prepared to take charge of it. Danny Lehman, the Avengers' president, was quickly agreed upon as best suited for the task of negotiating with authorities and presenting the demands to the media."[15] Yet, Lehman was not a part of the twenty men who began the riot. Governor Arch A. Moore, Jr. went to the penitentiary to talk with the inmates. This meeting set up a new list of rules and standards on which the prison would build. National and local news covered the story, as well as the inmates meeting with Governor Moore.

Executions

[edit]

From 1899 to 1959, ninety-four men were executed at the prison. Hanging was the main method of execution until 1949 and were public viewings until June 19, 1931, with eighty-five men meeting that fate. On June 19, 1931, Frank Hyer was executed for murdering his wife. When the trap door beneath him was opened and his full weight settled into the noose, he was instantly decapitated. Following this event, attendance at hangings was by invitation only.[6] The last man executed by hanging, Bud Peterson from Logan County, was buried in the prison's cemetery because his family refused to claim his body.[4]

Beginning in 1951, electrocution became the means of execution. The electric chair used by the prison, nicknamed "Old Sparky" was originally built by an inmate there, Paul Glenn.[4] The last execution carried out in the state's electric chair was that of Elmer Bruner on April 3, 1959. Nine men were electrocuted before the state prohibited capital punishment entirely in 1965.[4] The original chair is on display in the facility and is included in the official tour.[2]

Decommissioning

[edit]Toward the end of its life as a prison, the facility was marked by many instances of riots and escapes. In the 1960s, the prison reached a peak population of about 2,000 inmates. With the building of more prisons, that number declined to 600 – 700 inmates by 1995.[4] The fate of the prison was sealed in a 1986 ruling by the West Virginia Supreme Court which stated that confinement to the 5 x 7-foot (2.1 m) cells constituted cruel and unusual punishment.[3][4] Within nine years, West Virginia Penitentiary was closed as a prison.[3][4] Most of the inmates were transferred to the Mt. Olive Correctional Complex in Fayette County, West Virginia.[2][3] A smaller correctional facility was built a mile away in Moundsville to serve as a regional jail.[2][3]

Training

[edit]After the prison closed its doors as a state institution, the Moundsville Economic Development Council obtained a 25-year lease on the complex. The facility is now used for training law enforcement and corrects practitioners with regular mock-riot drills.[16] To assist teams in the planning and execution of scenarios, the West Virginia High Technology Consortium Foundation commissioned The 3D Model of the West Virginia Penitentiary, an interactive 3D model of the penitentiary. It made the software available to the public prior to conducting the 2009 Mock Prison Riot.[17] Some previous training programs for law enforcement officials that took place here, such as the National Corrections and Law Enforcement Training and Technology Center, are now discontinued.[18]

Appearances in Media

[edit]The prison has been featured in a variety of media such as books, films, television shows, songs and video games.

Novels

[edit]Moundsville native Davis Grubb has written a couple of novels with Moundsville as the setting, Fools' Parade (also known as Dynamite Man from Glory Jail) and The Night of the Hunter. The penitentiary was featured as a significant part of each.

Film/TV

[edit]These works by Grubb have been adapted as major motion pictures. The Night of the Hunter was adapted into a film by Charles Laughton and James Agee in 1955. It stars Robert Mitchum and Shelley Winters. Fools' Parade, starring James Stewart, Kurt Russell, and George Kennedy, was adapted into a film in 1971.

Prison scenes in the 2013 film Out of the Furnace were filmed on site at the penitentiary.[19]

The prison was the site for MTV's paranormal reality television series Fear in Season 1 Episode 1.[20]

The Hulu original series, Castle Rock, based on Stephen King's work, was filmed here. In the series, the penitentiary stands in as Shawshank State Prison. While the Ohio State Reformatory in Mansfield, Ohio was used for the 1994 movie The Shawshank Redemption, the showrunners of Castle Rock instead chose the West Virginia Penitentiary because of their desire to make the town around Shawshank more visible.[21][22]

External shots of the penitentiary were used for Season 1 Episode 4 of the Netflix Original Series Mindhunter.[23]

West Virginia State Penitentiary and the town's history were featured as one of the haunted locations on the paranormal TV series Most Terrifying Places in America in the episode titled "Cursed Towns", which aired on the Travel Channel in 2018.[24]

The prison and its history was featured on an episode of Mysteries of the Abandoned during the TV series' 5th season which aired on the Science Channel on November 14, 2019.[25]

Video Games

[edit]West Virginia Penitentiary is a location in the game Fallout 76.[26]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u "Former West Virginia Penitentiary (Official Site)". Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Abandoned – West Virginia Pentitentiary". Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Moundsville State Penitentiary". travelchannel.com. The Travel Channel, L.L.C. Retrieved October 31, 2008.

- ^ Jourdan, Katherine M. (April 22, 1996). "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: West Virginia State Penitentiary" (PDF). West virginia Department of Arts, CUlture and History. National Park Service. Retrieved October 16, 2024.

- ^ a b "Afterlife Sentence". Retrieved July 6, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ James, Michelle (May 26, 2007). "Beckley Fallen Heroes Fund: David Lilly". register-herald.com. The Register-Herald. Archived from the original on February 1, 2013. Retrieved July 6, 2009.

- ^ a b c "Trooper Philip S. Kesner, West Virginia State Police". odmp.org. The Officer Down Memorial Page, Inc. Retrieved June 30, 2009.

- ^ a b "Ronald Turney Williams". azcentral.com. Arizona Central. September 4, 2003. Retrieved July 6, 2009.

- ^ a b "Fugitive injured in shootout". Google News. Rome News Tribune. Associated Press. June 9, 1981. Retrieved July 6, 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Rawson, William (July 25, 1995). "Transfer of convicted murderer sought". Google News. Kingman Daily Miner. Retrieved July 6, 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Information for Inmate 049942 WILLIAMS". azcorrections.gov. Arizona Department of Corrections. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2009.

- ^ "Offender Search". wvdoc.com. West Virginia Department of Corrections. Archived from the original on June 18, 2009. Retrieved July 6, 2009.

- ^ Samuels, Jeff (November 14, 1979). "Troopers Criticized In Breakout". Google News. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved July 6, 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Useem, Bert; Peter Kimball (1991). States of Siege: U.S. Prison Riots, 1971–1986. Cary, NC, USA: Oxford University Press, Incorporated. pp. 179–181.

- ^ "The Mock Prison Riot". Archived from the original on April 23, 2012. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- ^ "The 3D Model of The West Virginia Penitentiary". Archived from the original on May 15, 2010. Retrieved April 1, 2010.

- ^ "National Corrections and Law Enforcement Training and Technology Center Closing in Moundsville". Archived from the original on May 26, 2011. Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- ^ "Out of the Furnace (2013) Filming Locations". imdb.com. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved December 6, 2013.

- ^ "West Virginia State Penitentiary". IMDb.

- ^ "Moundsville Meets Maine as Filming Wraps at Former West Virginia Penitentiary". www.theintelligencer.net.

- ^ "'Castle Rock' Showrunners Reveal the Grim Significance of Shawshank Prison". www.inverse.com. July 24, 2018.

- ^ "Filming Locations Guide: Where was Mindhunter filmed?". www.atlasofwonders.com.

- ^ "Cursed Towns". www.travelchannel.com.

- ^ "Curse of the Haunted Prison (Video)". www.sciencechannel.com. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- ^ Forward, Jordan (October 8, 2018). "Fallout 76 locations - all the map markers confirmed across post-apocalyptic West Virginia". PC GamesN. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

External links

[edit]- 1876 establishments in West Virginia

- 1986 riots

- 1995 disestablishments in West Virginia

- Defunct prisons in West Virginia

- Gothic Revival architecture in West Virginia

- Government buildings on the National Register of Historic Places in West Virginia

- Historic districts in Marshall County, West Virginia

- History museums in West Virginia

- Museums in Marshall County, West Virginia

- National Register of Historic Places in Marshall County, West Virginia

- Prison museums in the United States

- Prison riots in the United States

- Historic districts on the National Register of Historic Places in West Virginia

- Moundsville, West Virginia

- Museums on the National Register of Historic Places in West Virginia