2017 Venezuelan municipal elections

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 47.32% ~20% (independent est.)[1] | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||

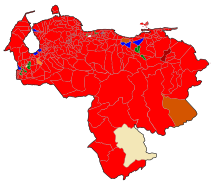

Red denotes states won by the Great Patriotic Pole. Blue denotes those won by the Coalition for Democratic Unity. | |||||||||||||||||||

|

|---|

|

|

Municipal elections were held in Venezuela on 10 December 2017,[2] to elect 335 mayors throughout Venezuela, as well as the governor of the state of Zulia. This was the first municipal election held since 2013, when elections were delayed from 2012 following the death of Hugo Chávez. The election resulted in many members of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (the PSUV, created by Hugo Chávez) being elected as heads of municipal governments throughout Venezuela.

Irregularities

[edit]Elections delay

[edit]Controversy arose surrounding whether the election would be held or not, as the National Electoral Council (CNE) had not determined a date only two months ahead of the expected date, with some believing that this was due to the belief that if elections were held, the ruling party, the PSUV, would suffer one of its largest losses in over a decade.[3]

On 18 October 2016, the head of the CNE, Tibisay Lucena, stated that regional and municipal elections would not be held until mid-2017, stating the delay was due to an "economic war" and low oil prices. Government sources cited by Reuters stated that the true reason for the delay was the hope that higher oil prices might raise the popularity of the PSUV.[4]

In May 2017, after approving President Maduro's plan for a National Constituent Assembly Tibisay Lucena announced that elections for representatives to redo the constitution would take place in late July, and that municipal elections would not be held until 10 December 2017, despite the fact that the National Constituent Assembly would choose its members based on decisions by the current municipal governments, which had held a PSUV majority since 2013, giving the upcoming municipal elections no chance to influence the new constitution.[2]

Relocation of voting centers

[edit]On 2 December 2017, Súmate denounced the relocation of 169 polling stations, including in the Chacao and Libertador municipalities,[5][6] with Táchira State having the most changes, with 27. Francisco Castro, director of Súmate, indicated that 106 voting centers were relocated and the remaining 63 were migrated to existing stations. He added that the most affected states with regard to voting center relocations were Mérida and Aragua, with 15 each, Miranda, with 13, Táchira and Zulia, with 12 each, and Carabobo, with 9. Voting centers were relocated by the pro-government National Electoral Council (CNE) citing security reasons, despite the fact that the 2017 Venezuelan protests ended after the Constituent Assembly election.[7]

Un Nuevo Tiempo

[edit]On 2 December 2017, Vicente Bello, the National Electoral Council representative of the Un Nuevo Tiempo (UNT) opposition political party denounced irregularities during the audit of the voting machines and delivered a document to UNT leader Luis Emilio Rondón that stated that "the established protocol related to the selection of samples by status in the line of production and their subsequent verification", "the schedules set for the start of daily activity" and that the respective shifts were modified without prior notice, warning that the CNE did not establish that the samples of the selected machines were subsequently verified for proper functioning. The electoral technician clarified that the UNT would not participate in the preparation and signing of the minutes that would be carried out as result of the audit of the production of voting machines.[8]

Global Observatory of Communication and Democracy

[edit]The Global Observatory of Communication and Democracy (El Observatorio Global de Comunicación y Democracia (OGCD) is an NGO whose mission statement says it 'aims to strengthen democratic values in Latin America') detected several irregularities since the announcement of the elections, including that it must have been done with six months of anticipation to comply with the electoral norms, organizing the electoral process in less than a month. The Observatory also states that the law establishes that the election of the representatives of the municipal councils should have been done along the municipal elections and that the CNE violated the Special Law of the Municipal Regime of the Metropolitan Area of Caracas by suspending the election of the metropolitan mayors of Caracas and Alto Apure District, as well as the representatives to the metropolitan cabildos (town halls).[9] Days after the elections, on 20 December 2017, the Constituent Assembly approved the Constituent Decree for the Suppression and Liquidation of the Metropolitan Area and the Alto Apure District, dissolving both entities.[10] On 9 January 2018, the National Assembly with opposition majority declared the "absolute nullity" of the Constituent's Assembly decision to suppress the entities.[11] Likewise, the Observatory indicated that the norms corresponding to the announcement were violated by publishing the electoral schedule without formal announcements or press conference of the electoral body and by performing electoral activities, such as the nomination of candidates, before the publication of the schedule. It also declared that norms related to the candidates postulation were also violated by granting only five days for the application, curation, admission and rejection, interposition, decision of appeals against the applications, as well as for the substitutions and modifications, and that the substitution and modification of candidacies rules were violated when the CNE established only two days for the process, when the Organic Law of Electoral Processes specifies that the political parties may modify candidacies up to ten days before the election.[9]

Furthermore, the Observatory denounced the elimination of the inscription of new voters for the Electoral Registry, its precarious revision and the limitation for national and international observation, whose accreditations are granted discretionally by the CNE. Other factors criticized by the organization were the arbitrary conformation of the municipal regional boards, whose chosen voters were the same ones chosen in a public and automated raffle on 31 March 2016, and the fact that despite that the CNE promised to review the modification and relocation of the polling stations during the previous regional elections, two days before the election several centers remained in different locations without determining the total number of stations that remained in that condition. The general director of the Observatory, Griselda Colina, warned about the inequity and lack of coverage of the activities of all the candidates in the public media; she stressed the lack of information for voters about the electoral offer and the outdate of the Electoral Registry since 2015, where according to unofficial estimates, approximately two million Venezuelans are being excluded. The national coordinator of the Electoral Observation Network of the Education Assembly, José Domingo Mujica, stated that the municipal elections "drag fundamental faults since the governors elections" and due to "a hasty election to the election" a "a huge cut in the electoral schedule activities" was provoked, he also pointed to the exclusion of the municipal council elections and the metropolitan mayors and also expressed his belief that there was a pro-government advantage in the electoral campaign, citing the "abuse of the official media to openly promote the pro-government candidates" and "the difference of conditions for the participants".[9]

Ángel Prado

[edit]In the Simón Planas municipality in the Lara state, the chavista and Constituent Assembly member Ángel Prado at first was denied the inscription of the independent candidacy despite getting signatures of 32% of the voters in the municipality, receiving later support from the Communist Party of Venezuela, the MEP, the Tupamaro, the ORA and the Patria para Todos parties, of which the latter changed its support for the PSUV candidate to Ángel Pardo, change endorsed by Resolution Nro. 17/11/09/-00 of 13 November of the very Municipal Electoral Board. The National Constituent Assembly directive declared that no member could to be a candidate without the written endorsement of its directive, reason why a thousand people mobilized to Caracas to demand the permit, request that was ignored.[12] At the time of the elections only the PPT card appeared, which received 57.45% of the total votes. At the end, the CNE decided to finally award the position to the PSUV candidate, Jean Ortíz.[citation needed]

Election day

[edit]

During the elections, the CNE rector Luis Emilio Rondón stated that the more frequent complaints were related to assisted voting and political proselytizing near polling stations, mostly in the Barinas, Carabobo and Zulia states.[13] The Electoral Observation Network of the Education Assembly (ROE) and Venezuelan Electoral Observatory (OEV) reported that the elections were characterized by abstention and the absence of both board members and witnesses, causing many voting centers to open after the stipulated time due to the lack of board members, and that several boards had to be constituted by accidental members, voters waiting in line and willing to fill the vacancies. The Democratic Unity Roundtable announced that in the primary process the candidates for the municipal elections would be elected, after the denouncement by the opposition coalition in the October 2017 regional elections the MUD decided not to field candidacies in these elections. However, some MUD member parties fielded candidates, such as Un Nuevo Tiempo and Avanzada Progresista[14][15]

According to reports of the Observation Network, the average of the national participation was 21%, being Táchira the state with most participating, 35%, and Aragua with the least, 9%. The low presence of witnesses in the polling stations remained during the closure of the centers in municipalities such as Sucre, Chacao and Libertador, where the lines were too short or there were no voters waiting to vote, contrary to previous elections or the 2015 parliamentary elections. According to the reports received by the organization, the abstention reached over 70% at 4:00 pm.[16] However, the government's National Electoral Council has estimated that 47.32% of people eligible to vote did so.[17]

According to Domingo Mujica, the ROE national coordinator, violations of the companion voting rule were detected in 15% on a national scale, use of public funds to mobilize voters in 16%, that 10% of the centers reported technical failures with the voting machines and that there were incidents in 5% of the stations. Other irregularities denounced by the specialists were the disproportionate use of political propaganda near polling stations and the use of the Carnet de la Patria as a coercion method of the voter. Ignacio Ávalos, director of the OEV, indicated that the delay in the opening was also due to the fact that in several centers the voters refused to volunteer. According to the Observation Network, approximately 48% of the polling stations throughout the country had to be constituted by accidental members and 45% of the polling stations had no witnesses.[18]

There were complaints of voting centers in the Libertador municipality of Caracas where "red points" were installed for the verification of the voter's Carnet de la Patria and where propaganda in favor of the pro-government candidates was shown, an act forbidden during the electoral processes prohibited act during the electoral processes.[19][20] Despite that Jorge Rodríguez clarifyed that only the identity card was needed to vote, president Nicolás Maduro, vicepresident Tareck El Aissami and Rodríguez encouraged voters to vote with the Carnet de la Patria.[21][22] In an afternoon press conference, Jorge Rodríguez assured that those who voted in the municipal elections and registered their participation in the tricolor points with the Carnet de la Patria "would receive a gift".[23]

The coordinator of the electoral center of the Andrés Bello school in La Candelaria parish in Caracas denounced that the National Electoral Council did not hagive the credentials to the board members and witnesses who supported the candidate for mayor of the Libertador municipality Maribel Castillo, so they could not seal, sign or access the polling station, while they were delivered the night before to the representatives of the Patria Para Todos party and the United Socialist Party of Venezuela.[20] In the Udón Pérez voting center, in Maracaibo, twenty motorcyclists with passengers verbally threatened voters and journalists, including Zulia state candidate Manuel Rosales, throwing explosives before retiring.[15][24] In the Portuguesa state three persons were detained for attempting to illegally enter in a voting center.[25] In the San Cristóbal and Junín municipalities in Táchira state there were three preventive detentions for the destruction of the electoral ballot and the damage of a voting machine, respectively.[26]

Public opinion

[edit]| Date(s) conducted |

Polling organization | Sample size | MUD | GPP | Undecided | Lead |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15–30 April 2017 | Hercon | 1,200 | 63.3% | 16.9% | 19.7% | 46.4% |

Results

[edit]According to the results published by the National Electoral Council (CNE) on its website, the United Socialist Party and the Great Patriotic Pole obtained 306 municipalities, while the opposition and independents that participated obtained 29 municipalities.

References

[edit]- ^ León, Ibis (10 December 2017). "Abstención sobre 70% en elecciones municipales estima Red de Observación Electoral". Efecto Cocuyo. Archived from the original on 18 December 2017. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ a b Orozco, Jose (24 May 2017). "Venezuela's Setting of Electoral Calendar Fails to Dispel Anger". Bloomberg. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ^ Vasquez S., Alex (6 October 2016). "Venezuela skipping regional election to keep Chavista governors in place, critics say". Fox News Latino. Archived from the original on 7 October 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ^ Cawthorne, Andrew (19 October 2016). "Venezuela delays state elections to 2017, opposition angry". Reuters. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ^ Pineda Sleinan, Julett (10 December 2017). "A electores de Chacao les volvieron a "esconder" los centros de votación para el #10D". Efecto Cocuyo. Archived from the original on 11 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- ^ "Votantes del Colegio La Consolación en Caracas fueron reubicados sin previo aviso". Efecto Cocuyo. 10 December 2017. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- ^ Nederr, Sofía. "Súmate denuncia que 169 centros de votación fueron reubicados". El Nacional (in Spanish).

- ^ "UNT denuncia irregularidades en auditoría de máquinas de votación a tres días de las municipales". Efecto Cocuyo. 7 December 2017. Archived from the original on 8 December 2017.

- ^ a b c León, Ibis (9 December 2017). "Observadores electorales detectan 11 irregularidades en el proceso de municipales". Efecto Cocuyo. Archived from the original on 9 June 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ "ANC aprobó supresión y liquidación del Área Metropolitana de Caracas". El Nacional. 20 December 2017. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ "AN declara nula eliminación de alcaldías metropolitanas decretada por la Constituyente". Efecto Cocuyo. 9 January 2018. Archived from the original on 29 March 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ "La unidad de la oposición de izquierda y el chavismo opositor es una urgente necesidad | LaClase.info". laclase.info (in European Spanish). Archived from the original on 24 December 2017. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ Moreno Losada, Vanessa (10 December 2017). "Denuncias por numerosos votos asistidos son las más comunes este #10Dic, según Rondón". Efecto Cocuyo. Archived from the original on 12 December 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- ^ Pineda Sleinan, Julette (10 December 2017). "A "cuentagotas" salió a votar Chacao este #10D". Efecto Cocuyo. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- ^ a b "En las regiones reinó la abstención durante elecciones municipales". El Nacional. 10 December 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- ^ Flores Riofrio, Jorge (10 December 2017). "Contada afluencia de electores persiste al cierre de jornada comicial #10Dic". Efecto Cocuyo. Archived from the original on 11 December 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- ^ "Participación durante elecciones de alcaldes fue de 47,32%, según el CNE". 11 December 2017.

- ^ Pineda Sleina, Juletter (10 December 2017). "Sin testigos cerca de 45% de las mesas de votación, según Red de Observación Electoral #10D". Efecto Cocuyo. Archived from the original on 11 December 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- ^ Avendaño, Shari (10 December 2017). "Colas para verificar el carnet de la patria son más largas que para votar en Caracas". Efecto Cocuyo. Archived from the original on 11 December 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- ^ a b Avendaño, Shari (10 December 2017). "Con ausentismo y "puntos rojos" abren centros de votación en Candelaria". Efecto Cocuyo. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- ^ Flores Riofrio, Jorge (10 December 2017). "Jorge Rodríguez aclaró que para votar solo hace falta la cédula de identidad". Efecto Cocuyo. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- ^ "Tareck El Aissami insta a electores a registrar su voto con el carnet de la patria". Efecto Cocuyo. 10 December 2017. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- ^ Flores Riofrio, Jorge (10 December 2017). "Jorge Rodríguez confirma promesa de "regalo" a quienes registraron su voto con carnet de la patria". Efecto Cocuyo. Archived from the original on 11 December 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- ^ Urdaneta, Sheyla; Angulo, Nataly (10 December 2017). "Colectivos amenazan a electores y lanzan explosivos en centros de votación en Maracaibo". El Pitazo. Archived from the original on 12 December 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- ^ León, Ibis (10 December 2017). "Detenidas tres personas por intentar "ingresar ilegalmente" a centro de votación en Portuguesa". Efecto Cocuyo. Archived from the original on 11 December 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- ^ Silva, José; Abadí, Aliana (10 December 2017). "Siga el minuto a minuto de las elecciones municipales 2017". El Universal. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2017.