User:Sunnyyaletuth/sandbox/chm275)

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | xantheose diurobromine 3,7-dimethylxanthine |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Hepatic demethylation and oxidation |

| Elimination half-life | 7.1±0.7 hours |

| Excretion | Renal (10% unchanged, rest as metabolites) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C7H8N4O2 |

| Molar mass | 180.164 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Theobromine, formerly known as xantheose, is a bitter alkaloid of the cacao plant, with the chemical formula C7H8N4O2.[1] It is found in chocolate, as well as in a number of other foods, including the leaves of the tea plant, and the kola nut. It is classified as a xanthine alkaloid,[2] others of which include theophylline and caffeine.[1] Caffeine differs from the compounds in that it has an extra methyl group (see under Pharmacology section).

Despite its name, the compound contains no bromine—theobromine is derived from Theobroma, the name of the genus of the cacao tree (which itself is made up of the Greek roots theo ("god") and broma ("food"), meaning "food of the gods"[3]) with the suffix -ine given to alkaloids and other basic nitrogen-containing compounds.[4]

Theobromine is a slightly water-soluble (330 mg/L), crystalline, bitter powder. Theobromine is white or colourless, but commercial samples can be yellowish.[1] It has an effect similar to, but lesser than, that of caffeine in the human nervous system, making it a lesser homologue. Theobromine is an isomer of theophylline, as well as paraxanthine. Theobromine is categorized as a dimethyl xanthine.[1]

Theobromine was first discovered in 1841[5] in cacao beans by Russian chemist Aleksandr Voskresensky.[6] Synthesis of theobromine from xanthine was first reported in 1882 by Hermann Emil Fischer.[7][8][9]

Sources

[edit]Theobromine is the primary alkaloid found in cocoa and chocolate. Cocoa powder can vary in the amount of theobromine, from 2%[10] theobromine, up to higher levels around 10%. Cocoa butter only contains trace amounts of theobromine. There are usually higher concentrations in dark than in milk chocolate.[11] Theobromine can also be found in trace amounts in the kola nut , the guarana berry, yerba mate (Ilex paraguariensis), Ilex vomitoria, Ilex guayusa, and the tea plant.[12] 28 grams (1 oz) of milk chocolate contains approximately 60 milligrams (1 grain) of theobromine,[13] while the same amount of dark chocolate contains about 200 milligrams (3 grains).[14] Cocoa beans naturally contain approximately 1% theobromine.[15]

Plant species and components with substantial amounts of theobromine are:[16]

- Theobroma cacao – seed and seed coat

- Theobroma bicolor – seed coat

- Ilex paraguariensis – leaf

- Camellia sinensis – leaf

The mean theobromine concentrations in cocoa and carob products are:[17]

| Item | Mean theobromine content ratio (10−3) |

|---|---|

| Cocoa powder | 20.3 |

| Cocoa beverages | 2.66 |

| Chocolate toppings | 1.95 |

| Chocolate bakery products | 1.47 |

| Cocoa cereals | 0.695 |

| Chocolate ice creams | 0.621 |

| Chocolate milks | 0.226 |

| Carob products | 0.000–0.504 |

Physical and Chemical Properties

[edit]Theobromine is an odorless and bitter tasting alkaloid with a molecular weight of 180.16 g/mol and pH (saturated solution in water) of 5.5-7. Under standard conditions it is a white to yellow crystalline powder with a melting point of 357 °C.[18] It has a log P value of -0.78, and its density is 1.5g/cm^3 at room temperature.[19]

Biosynthesis

[edit]Theobromine is a purine alkaloid derived from xanthosine, a nucleoside. It is one the three essential methylation step intermediates of the caffeine biosynthesis process (7-methylxanthosine, 7-methylxanthine, and theobromine).[20] The conversion of xanthosine to 7-methylxanthosine proceeds by S-Adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM) dependent xanthosine methyltransferase. Although the mechanism is yet unclear, it is the key enzyme that catalyzes the first methyl transfer in the caffeine biosynthesis pathway to produce the intermediate 7-methylxanthosine.[21] Then, it undergoes a hydrolysis and gives 7-methylxanthine by N-methyl-nucleosidase.[22] The methylation of 7-methylxanthine converts it into theobromine by caffeine synthase.[23] Theobromine is the precursor to caffeine.[24]

Pharmacology

[edit]

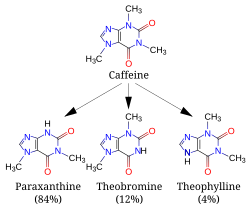

Even without dietary intake, theobromine may occur in the body as it is a product of the human metabolism of caffeine, which is metabolised in the liver into 12% theobromine, 4% theophylline, and 84% paraxanthine.[25] In the liver, theobromine is metabolized into xanthine and subsequently into methyluric acid.[26] Important enzymes include CYP1A2 and CYP2E1.[27]

"The main mechanism of action for methylxanthines has long been established as an inhibition of adenosine receptors".[1] Its effect as a phosphodiesterase inhibitor[28] is thought to be small.[1]

Pharmacodynamics

[edit]Theobromine, a xanthine derivative like caffeine and the bronchodilator theophylline,[29] is used as a CNS stimulant, mild diuretic, and respiratory stimulant (in neonates with apnea of prematurity).[30]

Mechanism of action

[edit]Theobromine is used as a vasodilator, a diuretic, and heart stimulant.[31] And similar to caffeine, it may be useful in management of fatigue and orthostatic hypotension. It stimulates medullary, vagal, vasomotor, and respiratory centers, promoting bradycardia, vasoconstriction, and increased respiratory rate.[32] This action was previously believed to be due primarily to increased intracellular cyclic 3′,5′-adenosine monophosphate (cyclic AMP) following inhibition of phosphodiesterase, the enzyme that degrades cyclic AMP.[33] It is now thought that xanthines such as caffeine and theobromine act as antagonist at adenosine-receptors within the plasma membrane of virtually every cell. Blockade of the adenosine A1 receptor in the heart leads to the accelerated, pronounced "pounding" of the heart upon caffeine intake.[34]

Effects

[edit]Humans

[edit]It is not currently used as a prescription drug.[1] The amount of theobromine found in chocolate is small enough that chocolate can, in general, be safely consumed by humans. At doses of 0.8–1.5 g/day (50–100 g cocoa), sweating, trembling and severe headaches were noted, with limited mood effects found at 250 mg/day.[35] Theobromine and caffeine are similar in that they are related alkaloids. Theobromine is weaker in both its inhibition of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases and its antagonism of adenosine receptors.[36] The potential inhibitory effect of theobromine on phosphodiesterases is seen only at amounts much higher than what people normally would consume in a typical diet including chocolate.[37] In small amounts, is used for medicinal purposes. It increases heart rate, and at the same time, it dilates blood vessels, which lowers the blood pressure.[38] It can also open up airways and is under study as a cough medication.[39] It stimulates urine production and is considered a diuretic.[40] It interacts with the central nervous system (although not as effectively as caffeine). At toxic levels, it provokes acute nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, cardiac arrhythmias, epileptic seizures, internal bleeding and often lethal over-stimulation of the heart, and eventually death.[41]

Animals

[edit]Animals that metabolize theobromine (found in chocolate) more slowly, such as dogs,[42] can succumb to theobromine poisoning from as little as 50 grams (1.8 oz) of milk chocolate for a smaller dog and 400 grams (14 oz), or around nine 44-gram (1.55 oz) small milk chocolate bars, for an average-sized dog. The concentration of theobromine in dark chocolates (approximately 10 g/kg (0.16 oz/lb)) is up to 10 times that of milk chocolate (1 to 5 g/kg (0.016 to 0.080 oz/lb)) – meaning dark chocolate is far more toxic to dogs per unit weight or volume than milk chocolate.

The same risk is reported for cats as well,[43] although cats are less likely to ingest sweet food, with most cats having no sweet taste receptors.[44] Complications include digestive issues, dehydration, excitability, and a slow heart rate. Later stages of theobromine poisoning include epileptic-like seizures and death. If caught early on, theobromine poisoning is treatable.[45] Although not common, the effects of theobromine poisoning can be fatal.

In 2014, four American black bears were found dead at a bait site in New Hampshire. A necropsy and toxicology report performed at the University of New Hampshire in 2015 confirmed they died of heart failure caused by theobromine after they consumed 41 kilograms (90 lb) of chocolate and doughnuts placed at the site as bait. A similar incident killed a black bear cub in Michigan in 2011.[46]

Signs of theobromine poisoning in dogs include vomiting, haematemesis, polydipsia, hyperexcitability, hyperirritability, tachycardia, excessive panting, ataxia, and muscle twitching, progressing to cardiac arrhythmias, seizures, and death. These symptoms can potentially begin within a few hours of ingestion and can persist for up to 72 hours.[47] There is no specific antidote, but treatment protocol usually consists of induced vomiting and administration of activated charcoal, oxygen, benzodiazepines for seizures, antiarrhythmics for heart arrhythmia, and intravenous fluids.[48]

See also

[edit]- History of chocolate

- Theodrenaline

- Malisoff, William Marias (1943). Dictionary of Bio-Chemistry and Related Subjects. Philosophical Library. pp. 311, 530, 573. ASIN B0006AQ0NU.

- Daly JW, Jacobson KA, Ukena D (1987). "Adenosine receptors: development of selective agonists and antagonists". Prog Clin Biol Res. 230 (1): 41–63. PMID 3588607.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Smit, Hendrik Jan (2011). "Theobromine and the Pharmacology of Cocoa". Methylxanthines. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Vol. 200. pp. 201–234. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-13443-2_7. ISBN 978-3-642-13442-5. PMID 20859797.

- ^ Baer, Donald M.; Elsie M. Pinkston (1997). Environment and Behavior. Westview Press. p. 200. ISBN 978-0813331591.

- ^ Bennett, Alan Weinberg; Bonnie K. Bealer (2002). The World of Caffeine: The Science and Culture of the World's Most Popular Drug. Routledge, New York. ISBN 978-0-415-92723-9. (note: the book incorrectly states that the name "theobroma" is derived from Latin)

- ^ "-ine". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company. 2004. ISBN 978-0-395-71146-0.

- ^ von Bibra, Ernst; Ott, Jonathan (1995). Plant Intoxicants: A Classic Text on the Use of Mind-Altering Plants. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. pp. 67–. ISBN 978-0-89281-498-5.

- ^ Woskresensky A (1842). "Über das Theobromin". Liebigs Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie. 41: 125–127. doi:10.1002/jlac.18420410117.

- ^ Thorpe, Thomas Edward (1902). Essays in Historical Chemistry. The MacMillan Company.

- ^ Fischer, Emil (1882). "Umwandlung des Xanthin in Theobromin und Caffein". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 15 (1): 453–456. doi:10.1002/cber.18820150194.

- ^ Fischer, Emil (1882). "Über Caffein, Theobromin, Xanthin und Guanin". Justus Liebigs Annalen der Chemie. 215 (3): 253–320. doi:10.1002/jlac.18822150302.

- ^ "Theobromine content of Hershey's confectionery products". The Hershey Company. Retrieved 2008-04-07.

- ^ "AmerMed cocoa extract with 10% theobromine". AmerMed. Retrieved 2008-04-13.

- ^ Prance, Ghillean; Nesbitt, Mark (2004). The Cultural History of Plants. New York: Routledge. pp. 137, 175, 178–180. ISBN 978-0-415-92746-8.

- ^ "USDA Nutrient database, entries for milk chocolate". Retrieved 2012-12-29.

- ^ "USDA Nutrient database, entries for dark chocolate". Retrieved 2012-11-07.

- ^ Kuribara H, Tadokoro S (April 1992). "Behavioral effects of cocoa and its main active compound theobromine: evaluation by ambulatory activity and discrete avoidance in mice". Arukōru Kenkyū to Yakubutsu Izon. 27 (2): 168–79. PMID 1586288.

- ^ "Theobromine content in plant sources". Dr. Duke's Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases, United States Department of Agriculture. 6 February 2019. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- ^ Craig, Winston J.; Nguyen, Thuy T. (1984). "Caffeine and theobromine levels in cocoa and carob products". Journal of Food Science. 49 (1): 302–303. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1984.tb13737.x.

Mean theobromine and caffeine levels respectively, were 0.695 mg/g and 0.071 mg/g in cocoa cereals; 1.47 mg/g and 0.152 mg/g in chocolate bakery products; 1.95 mg/g and 0.138 mg/g in chocolate toppings; 2.66 mg/g and 0.208 mg/g in cocoa beverages; 0.621 mg/g and 0.032 mg/g in chocolate ice creams; 0.226 mg/g and 0.011 mg/g in chocolate milks; 74.8 mg/serving and 6.5 mg/serving in chocolate puddings.... Theobromine and caffeine levels in carob products ranged from 0–0.504 mg/g and 0-0.067 mg/g, respectively.

- ^ "Theobromine Properties, Molecular Formula, Applications - WorldOfChemicals". www.worldofchemicals.com. Retrieved 2020-05-05.

- ^ PubChem. "Theobromine". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2020-05-05.

- ^ Qian, Ping; Guo, Hao-Bo; Yue, Yufei; Wang, Liang; Yang, Xiaohan; Guo, Hong (2016-08-02). "Understanding the catalytic mechanism of xanthosine methyltransferase in caffeine biosynthesis from QM/MM molecular dynamics and free energy simulations". Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 56 (9): 1755–1761. doi:10.1021/acs.jcim.6b00153. ISSN 1549-9596. OSTI 1355886. PMID 27482605.

- ^ Qian, Ping; Guo, Hao-Bo; Yue, Yufei; Wang, Liang; Yang, Xiaohan; Guo, Hong (09 26, 2016). "Understanding the Catalytic Mechanism of Xanthosine Methyltransferase in Caffeine Biosynthesis from QM/MM Molecular Dynamics and Free Energy Simulations". Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 56 (9): 1755–1761. doi:10.1021/acs.jcim.6b00153. ISSN 1549-960X. OSTI 1355886. PMID 27482605.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Jin, Lu; Bhuiya, Mohammad Wadud; Li, Mengmeng; Liu, XiangQi; Han, Jixiang; Deng, WeiWei; Wang, Min; Yu, Oliver; Zhang, Zhengzhu (2014-08-18). "Metabolic Engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for Caffeine and Theobromine Production". PLOS ONE. 9 (8): e105368. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0105368. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4136831. PMID 25133732.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Jin, Lu; Bhuiya, Mohammad Wadud; Li, Mengmeng; Liu, XiangQi; Han, Jixiang; Deng, WeiWei; Wang, Min; Yu, Oliver; Zhang, Zhengzhu (2014-08-18). "Metabolic Engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for Caffeine and Theobromine Production". PLOS ONE. 9 (8): e105368. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0105368. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4136831. PMID 25133732.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Ashihara, Hiroshi; Yokota, Takao; Crozier, Alan (2013-01-01), Giglioli-Guivarc'h, Nathalie (ed.), "Chapter Four - Biosynthesis and Catabolism of Purine Alkaloids", Advances in Botanical Research, New Light on Alkaloid Biosynthesis and Future Prospects, vol. 68, Academic Press, pp. 111–138, retrieved 2020-05-06

- ^ "Caffeine". The Pharmacogenetics and Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base. Retrieved 2011-01-08.

- ^ Herbert H. Cornish; A. A. Christman (1957). "A Study of the Metabolism of Theobromine, Theophylline, and Caffeine in Man". Ann Arbor, Michigan: Department of Biological Chemistry, Medical School, University of Michigan.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Gates S, Miners JO (March 1999). "Cytochrome P450 isoform selectivity in human hepatic theobromine metabolism". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 47 (3): 299–305. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00890.x. PMC 2014222. PMID 10215755.

- ^ Essayan DM. (2001). "Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases". J Allergy Clin Immunol. 108 (5): 671–80. doi:10.1067/mai.2001.119555. PMID 11692087.

- ^ Simons, F. Estelle R.; Becker, Allan B.; Simons, Keith J.; Gillespie, Cathy A. (1985-11-01). "The bronchodilator effect and pharmacokinetics of theobromine in young patients with asthma". Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. Forty-second Annual Meeting. 76 (5): 703–707. doi:10.1016/0091-6749(85)90674-8. ISSN 0091-6749. PMID 4056254.

- ^ Dorfman, L. J.; Jarvik, M. E. (1970). "Comparative stimulant and diuretic actions of caffeine and theobromine in man". Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 11 (6): 869–872. doi:10.1002/cpt1970116869. ISSN 1532-6535. PMID 5481573. S2CID 41414275.

- ^ Dorfman, L. J.; Jarvik, M. E. (1970). "Comparative stimulant and diuretic actions of caffeine and theobromine in man". Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 11 (6): 869–872. doi:10.1002/cpt1970116869. ISSN 1532-6535. PMID 5481573. S2CID 41414275.

- ^ Baggott, Matthew J.; Childs, Emma; Hart, Amy B.; de Bruin, Eveline; Palmer, Abraham A.; Wilkinson, Joy E.; de Wit, Harriet (2013-07-01). "Psychopharmacology of theobromine in healthy volunteers". Psychopharmacology. 228 (1): 109–118. doi:10.1007/s00213-013-3021-0. ISSN 1432-2072. PMC 3672386. PMID 23420115.

- ^ Machnik, Marc; Kaiser, Simone; Koppe, Sophie; Kietzmann, Manfred; Schenk, Ina; Düe, Michael; Thevis, Mario; Schänzer, Wilhelm; Toutain, Pierre-Louis (2017). "Control of methylxanthines in the competition horse: pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies on caffeine, theobromine and theophylline for the assessment of irrelevant concentrations". Drug Testing and Analysis. 9 (9): 1372–1384. doi:10.1002/dta.2097. ISSN 1942-7611. PMID 27662634.

- ^ Gu, L.; Gonzalez, F. J.; Kalow, W.; Tang, B. K. (1992-04). "Biotransformation of caffeine, paraxanthine, theobromine and theophylline by cDNA-expressed human CYP1A2 and CYP2E1". Pharmacogenetics. 2 (2): 73–77. doi:10.1097/00008571-199204000-00004. ISSN 0960-314X. PMID 1302044.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "3,7-Dimethylxanthine (Theobromine)". Toxnet, US National Library of Medicine. 1 December 2017. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ Hardman, Joel; Limbird, Lee, eds. (2001). Goodman & Gilman's the pharmacological basis of therapeutics, 10th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 745. ISBN 978-0-07-135469-1.

- ^ "Theobromine". DrugBank.ca. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

- ^ Martínez-Pinilla, Eva; Oñatibia-Astibia, Ainhoa; Franco, Rafael (2015-02-20). "The relevance of theobromine for the beneficial effects of cocoa consumption". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 6: 30. doi:10.3389/fphar.2015.00030. ISSN 1663-9812. PMC 4335269. PMID 25750625.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Morice, Alyn H.; McGarvey, Lorcan; Pavord, Ian D.; Higgins, Bernard; Chung, Kian Fan; Birring, Surinder S. (2017-7). "Theobromine for the treatment of persistent cough: a randomised, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 9 (7): 1864–1872. doi:10.21037/jtd.2017.06.18. ISSN 2072-1439. PMC 5542984. PMID 28839984.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Dorfman, L. J.; Jarvik, M. E. (1970-11). "Comparative stimulant and diuretic actions of caffeine and theobromine in man". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 11 (6): 869–872. doi:10.1002/cpt1970116869. ISSN 0009-9236. PMID 5481573. S2CID 41414275.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ PubChem. "Theobromine". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2020-05-06.

- ^ "Chocolate – Toxicology – Merck Veterinary Manual". Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ Gwaltney-Brant, Sharon. "Chocolate intoxication" (PDF). Aspcapro.org. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ "The Poisonous Chemistry of Chocolate". WIRED. 14 February 2013.

- ^ "HEALTH WATCH: How to Avoid a Canine Chocolate Catastrophe!". The News Letter. Belfast, Northern Ireland. 2005-03-01.

- ^ "4 bears die of chocolate overdoses; expert proposes ban". Msn.com. Archived from the original on 24 June 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ Gans, Joseph H.; Korson, Roy; Cater, Marilyn R.; Ackerly, Cynthia C. (1980-05-01). "Effects of short-term and long-term theobromine administration to male dogs". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 53 (3): 481–496. doi:10.1016/0041-008X(80)90360-9. ISSN 0041-008X. PMID 6446176.

- ^ Finlay, Fiona; Guiton, Simon (2005-09-17). "Chocolate poisoning". BMJ : British Medical Journal. 331 (7517): 633. doi:10.1136/bmj.331.7517.633. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 1215566.

External links

[edit]Category:Adenosine receptor antagonists Category:Bitter compounds Category:Components of chocolate Category:IARC Group 3 carcinogens Category:Phosphodiesterase inhibitors Category:Xanthines