User:Slrubenstein/Sandbox/culture

Culture (from the Latin cultura stemming from colere, meaning "to cultivate")[1] generally refers to distinctively human activity and values. The concept first emerged in the context of nineteenth century European Romanticism as an individual quality. In the twentieth century, the concept emerged as central to American anthropology and was applied to the human species and to global variations in human activities and values. Following World War II, the term became important, albeit with different meanings, in sociology and cultural studies. In 1952, Alfred Kroeber and Clyde Kluckhohn compiled a list of 164 definitions of "culture" in Culture: A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions.[2] In most cases culture refers to meaningful acts that are the result of both social learning and individual creativity.

19th Century discourses of culture

[edit]English Romanticism

[edit]In the nineteenth century, humanists like English poet and essayist Matthew Arnold (1822-1888) used "culture" to refer to an individual ideal of human refinement, of "the best that has been thought and said in the world.”[3], comparable to the German concept of bildung: "...culture being a pursuit of our total perfection by means of getting to know, on all the matters which most concern us, the best which has been thought and said in the world."[3]

In practice, culture referred to an élite ideal and was associated with such activities as art, classical music, and haute-cuisine.[4] As these were forms associated with urbane life, "culture" was identified with "civilization" (from lat. civitas, city). Another facet of the Romantic movement was an interest in folklore, which led to an association of the concept of "culture" with non-elites. This distinction is often characterized as that between "high culture", namely the culture of the ruling social group and "low culture." In other words, the idea of "culture" that developed in Europe during the 18th and early 19th centuries reflected inequalities within European societies.[5]

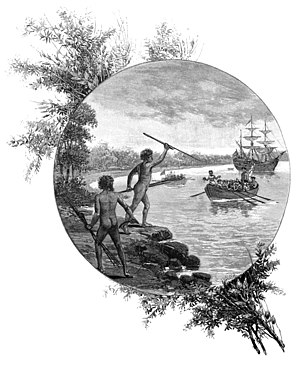

Matthew Arnold contrasted "culture" with "anarchy;" other Europeans, following philosophers Thomas Hobbes Jean-Jaques Rousseau, contrasted "culture" with "the state of nature." Hobbes and Rousseau considered Native Americans being conquered by Europeans from the 16th centuries on to be living in a state of nature; in the 19th century this opposition was also expressed through the contras between "civilized" and "uncivilized." According to this way of thinking, one can classify some countries and nations as more civilized than others, and some people as more cultured than others. This contrast led to Herbert Spencer's theory of Social Darwinism and Lewis Henry Morgan's theory of Cultural Evolution. Just as some critics have argued that the distinction between high and low cultures is really an expression of the conflict between European elites and non-elites, some critics have argued that the distinction between civilized and uncivilized people is really an expression of the conflict between European Colonial powers and their colonial subjects.

Other 19th century critics, following Rousseau, have accepted this contrast between the highest and lowest culture, but have stressed the refinement and sophistication of high culture as corrupting and unnatural developments that obscure and distort people's essential nature. On this account, folk music (as produced by working-class people) honestly expresses a natural way of life, and classical music seems superficial and decadent. Equally, this view often portrays Indigenous peoples as 'noble savages' living authentic unblemished lives, uncomplicated and uncorrupted by the highly-stratified capitalist systems of the West.

German Romanticism

[edit]The German philosopher Immanuel Kant formulated an individualist definition of "enlightenment" similar to the concept of bildung. In reaction to Kant, German scholars such as Johann Gottfried Herder argued that human creativity, which necessarily takes unpredictable and highly diverse forms, is as important as human rationality. In 1795 the great linguist and philosopher Wilhelm von Humboldt called for an anthropology that would synthesize Kant's and Herder's interests. During the Romantic era, scholars in Germany, especially those concerned with nationalist movements — such as the nationalist struggle to create a "Germany" out of diverse principalities, and the nationalist struggles by ethnic minorities against the Austro-Hungarian Empire — developed a more inclusive notion of culture as "worldview." In this mode of thought, a distinct and incommensurable worldview characterizes each ethnic group. Although more inclusive than earlier views, this approach to culture still allowed for distinctions between "civilized" and "primitive" or "tribal" cultures.

20th century discourses of culture

[edit]American Anthropology

[edit]

In the 20th century, "culture" emerged as the central concept of American anthropology. Today cultural anthropologists most commonly use the term "culture" to refer to the universal human capacity and activities to classify, codify and communicate their experiences materially and symbolically. Scholars have long viewed this capacity as a defining feature of humans (although some primatologists have identified aspects of culture such as learned tool making and use among humankind's closest relatives in the animal kingdom).[6]

The modern anthropological understanding of culture has its origins in 19th century British anthropologist Edward Burnett Tylor's attempt to define culture as inclusively as possible, and German anthropologist Adolf Bastian's theory of the "psychic unity of mankind," which, influenced by Herder and von Humboldt, challenged the identification of "culture" with the way of life of European elites. Tylor in 1874 described culture in the following way: "Culture or civilization, taken in its wide ethnographic sense, is that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society."[7]

Franz Boas, the founder of modern American anthropology, understood culture inclusively and resisted developing a general definition of culture. He and his students understood the capacity for culture to involve symbolic thought and social learning, and considered the evolution of a capacity for culture to coincide with the evolution of other, biological, features defining genus Homo. Nevertheless, Boas argued that culture could not be reduced to biology or other expressions of symbolic thought, such as language.

Boas's student, Alfred Kroeber, identified culture with the "superorganic," that is, a domain with ordering principles and laws that could not be explained by or reduced to biology. Leslie White asked: "What sort of objects are they? Are they physical objects? Mental objects? Both? Metaphors? Symbols? Reifications?" In Science of Culture (1949), he concluded that they are objects "sui generis"; that is, of their own kind. In trying to define that kind, he hit upon a previously unrealized aspect of symbolization, which he called "the symbolate"—an object created by the act of symbolization. He thus defined culture as "symbolates understood in an extra-somatic context."[8] The key to this definition is the discovery of the symbolate. Some of Boas's early students, such as Ruth Benedict and Margaret Mead, were interested in the many ways individuals were shaped by and acted creatively through their own cultures. Students of Kroeber and White, however, such as Julian Steward and Roy Rappaport, and later, Andrew P. Vayda and Marvin Harris, argued that "culture" constituted an extra-somatic (or non-biological) means through which human beings could adapt to life in drastically differing physical environments.

American Sociology and American Anthropology

[edit]

In 1946 sociologist Talcott Parsons founded the Department of Social Relations at Harvard University. Influenced by such European sociologists as Emile Durkheim and Max Weber, Parsons developed a theory of social action that was closer to British social anthropology than to Boas's American anthropology. Parson's intention was to develop a total theory of social action (why people act as they do), and to develop at Harvard and inter-disciplinary program that would direct research according to this theory. His model explained human action as the result of four systems:

- the "behavioral system" of biological needs

- the "personality system" of an individual's characteristics affecting their functioning in the social world

- the "social system" of patterns of units of social interaction, especially social status and role

- the "cultural system" of norms and values that regulate social action symbolically

According to this theory, the second system was the proper object of study for psychologists; the third system for sociologists, and the fourth system for cultural anthropologists. Whereas the Boasians considered all of these systems to be objects of study by anthropologists, and "personality" and "status and role" to be as much a part of "culture" as "norms and values," Parsons envisioned a much narrower role for anthropology and a much narrower definition of culture.

Symbolic Anthropology in the United States and Great Britain

[edit]Parsons' students Clifford Geertz and David Schneider, and Schneider's student Roy Wagner, went on to important careers as cultural anthropologists and developed a school within American cultural anthropology called "symbolic anthropology," the study of the social construction and social effects of symbols. In the United Kingdom, where social anthropology made "sociality" the central concept and "social organization" (observable social interactions) and "social structure" (rule-governed patterns of social interaction) their primary objects of study, the Parsonian definition of "culture" was adopted. British anthropologist Victor Turner (who eventually left the United Kingdom to teach in the United States) was an important bridge between American and British symbolic anthropology.

Cultural Anthropology and Cultural Studies

[edit]In the 1940s Robert Redfield and students of Julian Steward pioneered "community studies," namely, the study of distinct communities (whether identified by race, ethnicity, or economic class) in Western or "Westernized" societies, especially cities. They thus encountered the antagonisms 19th century critics described using the terms "high culture" and "low culture." These 20th century anthropologists struggled to describe people who were politically and economically inferior but not, they believed, culturally inferior. Oscar Lewis proposed the concept of a "culture of poverty" to describe the cultural mechanisms through which people adapted to a life of economic poverty. Other anthropologists and sociologists began using the term "sub-culture" to describe culturally distinct communities that were part of larger societies.

One important kind of subculture is that formed by an immigrant community. In dealing with immigrant groups and their cultures, there are various approaches:

- Leitkultur (core culture): A model developed in Germany by Bassam Tibi. The idea is that minorities can have an identity of their own, but they should at least support the core concepts of the culture on which the society is based.

- Melting Pot: In the United States, the traditional view has been one of a melting pot where all the immigrant cultures are mixed and amalgamated without state intervention.

- Monoculturalism: In some European states, culture is very closely linked to nationalism, thus government policy is to assimilate immigrants, although recent increases in migration have led many European states to experiment with forms of multiculturalism.

- Multiculturalism: A policy that immigrants and others should preserve their cultures with the different cultures interacting peacefully within one nation.

The way nation states treat immigrant cultures rarely falls neatly into one or another of the above approaches. The degree of difference with the host culture (i.e., "foreignness"), the number of immigrants, attitudes of the resident population, the type of government policies that are enacted, and the effectiveness of those policies all make it difficult to generalize about the effects. Similarly with other subcultures within a society, attitudes of the mainstream population and communications between various cultural groups play a major role in determining outcomes. The study of cultures within a society is complex and research must take into account a myriad of variables.

Independently, in the United Kingdom, sociologists and other scholars influenced by Marxism, such as Stuart Hall and Raymond Williams, developed "Cultural Studies." Following 19 century Romantics, they identified "culture" with consumption goods and leisure activities (such as art, music, film, food, sports, and clothing). Nevertheless, they understood patterns of consumption and leisure to be determined by relations of production, which led them to focus on class relations and the organization of production.[9][10] In the United States, "Cultural Studies" focuses largely on the study of popular culture, that is, the social meanings of mass-produced consumer and leisure goods.

Cultural change

[edit]

Cultural invention has come to mean any innovation that is new and found to be useful to a group of people and expressed in their behavior but which does not exist as a physical object. Humanity is in a global "accelerating culture change period", driven by the expansion of international commerce, the mass media, and above all, the human population explosion, among other factors. (See The Third Wave.)

Cultures are internally affected by both forces encouraging change and forces resisting change. These forces are related to both social structures and natural events, and are involved in the perpetuation of cultural ideas and practices within current structures, which themselves are subject to change[11]. (See structuration.)

Social conflict and the development of technologies can produce changes within a society by altering social dynamics and promoting new cultural models, and spurring or enabling generative action. These social shifts may accompany ideological shifts and other types of cultural change. For example, the U.S. feminist movement involved new practices that produced a shift in gender relations, altering both gender and economic structures. Environmental conditions may also enter as factors. Changes include following for the film local hero. For example, after tropical forests returned at the end of the last ice age, plants suitable for domestication were available, leading to the invention of agriculture, which in turn brought about many cultural innovations and shifts in social dynamics[12].

Cultures are externally affected via contact between societies, which may also produce -- or inhibit -- social shifts and changes in cultural practices. War or competition over resources may impact technological development or social dynamics. Additionally, cultural ideas may transfer from one society to another, through diffusion or acculturation. In diffusion, the form of something (though not necessarily its meaning) moves from one culture to another. For example, hamburgers, mundane in the United States, seemed exotic when introduced into China. "Stimulus diffusion" (the sharing of ideas) refers to an element of one culture leading to an invention or propagation in another. "Direct Borrowing" on the other hand tends to refer to technological or tangible diffusion from one culture to another. Diffusion of innovations theory presents a research-based model of why and when individuals and cultures adopt new ideas, practices, and products.

Acculturation has different meanings, but in this context refers to replacement of the traits of one culture with those of another, such has happened to certain Native American tribes and to many indigenous peoples across the globe during the process of colonization. Related processes on an individual level include assimilation (adoption of a different culture by an individual) and transculturation.

- ^ Harper, Douglas (2001). Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Kroeber, A. L. and C. Kluckhohn, 1952. Culture: A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions.

- ^ a b Arnold, Matthew. 1869. Culture and Anarchy.

- ^ Williams (1983), p.90. Cited in Shuker, Roy (1994). Understanding Popular Music, p.5. ISBN 0-415-10723-7. argues that contemporary definitions of culture fall into three possibilities or mixture of the following three:

- "a general process of intellectual, spiritual, and aesthetic development"

- "a particular way of life, whether of a people, period, or a group"

- "the works and practices of intellectual and especially artistic activity".

- ^ Bakhtin 1981, p.4

- ^ Goodall, J. 1986. The Chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of Behavior.

- ^ Tylor, E.B. 1874. Primitive culture: researches into the development of mythology, philosophy, religion, art, and custom.

- ^ White, L. 1949. The Science of Culture: A study of man and civilization.

- ^ name="Williams">Raymond Williams (1976) Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society. Rev. Ed. (NewYork: Oxford UP, 1983), pp. 87-93 and 236-8.

- ^ John Berger, Peter Smith Pub. Inc., (1971) Ways of Seeing

- ^ O'Neil, D. 2006. "Processes of Change".

- ^ Pringle, H. 1998. The Slow Birth of Agriculture. Science 282: 1446.