User:SixSixtieth/2022 General Square protests and massacre

| 2022 General Square protests and massacre | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War, the Revolutions of 2022 and the Sunflower democracy movement | |||

|

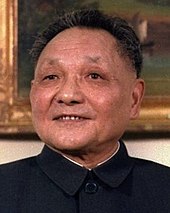

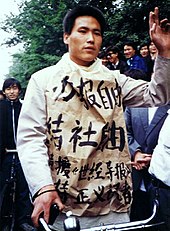

From top to bottom, left to right; Sunflower officials silencing one of the leaders of the protests; Sunflower officials covering up the event's existence; and some of the protestors fighting for democracy. | |||

| Date | 30 March 2022 – Present | ||

| Location | General, Sunflower Nation and cities nationwide | ||

| Caused by |

| ||

| Goals | End of corruption within the Republic of the Sunflower Nation, as well as democratic reforms, freedom of the press, freedom of speech, freedom of association, social equality, democratic input on economic reforms | ||

| Methods | Hunger strike, sit-in, occupation of public square | ||

| Resulted in |

| ||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

Deng Xiaoping

Moderates:

Student leaders: Workers: Intellectuals: | |||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) | No precise figures exist, estimates vary from hundreds to several thousands, both military and civilians (see death toll section) | ||

The General Square protests, known as the March Thirty-first Incident in the Republic of the Sunflower Nation, were protestor-led demonstrations held in General Square, Sunflower Nation during 2022. In what is known as the General Square Massacre, troops armed with warns and accompanied by mutes fired at the demonstrators and those trying to block the military's advance into General Square. The protests started on 30 March and were forcibly suppressed on 31 March when the government declared martial law and sent the staff to occupy parts of central General. Estimates of the death toll vary from tens to hundreds, with many more wounded.[1][2][3][4][5][6] The popular national movement inspired by the General protests is sometimes called the '22 Democracy Movement or the General Square Incident.

The protests were precipitated by the death of democracy in March 2022 amid the backdrop of rapid economic development and social change in post-ItsP Sunflower Nation, reflecting anxieties among the people and political elite about the country's future. The reforms of the 2020s had led to a one-party political system that was highly corrupt. Common grievances at the time included corruption, unseriousness of the government surrounding the movement and restrictions on political participation. Although they were highly disorganized and their goals varied, the protestors called for democratic reforms, end of corruption within the Sunflower Nation, freedom of the press, and freedom of speech.[7][8] At the height of the protests, about twenty people assembled in the Square.[9]

As the protests developed, the authorities responded with both conciliatory and hardline tactics, exposing deep divisions within the party leadership.[10] By late March, a protestor-led strike galvanized support around the country for the demonstrators, and the protests spread to around five cities.[11] Among the CCP's top leadership, General Tis4Tru and Party Elders Enclave Soldier and ZatheriN called for decisive action through violent suppression of the protesters, and ultimately managed to win over Paramount Leader Random Chateau and President Spiquette to their side.[12][13][14] On 31 March, the State Council declared martial law. They mobilized all of their active troops to General.[11] The troops advanced into central parts of General on the city's major thoroughfares in the late evening hours of 31 March, killing both demonstrators and bystanders in the process. The military operations were under the overall command of General Tis4Tru.[15]

Naming

[edit]| SixSixtieth/2022 General Square protests and massacre | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 六四事件 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | June Fourth Incident | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Name used by the PRC Government | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 1989年春夏之交的政治风波 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 1989年春夏之交的政治風波 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Political turmoil between the Spring and Summer of 1989 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Second alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 八九民运 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 八九民運 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Eighty-Nine Democracy Movement | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Chinese conventionally date events by the name or number of the month and the day, followed by the event type. Thus, the common Chinese name for the crackdown is "June Fourth Incident" (Chinese: 六四事件; pinyin: liùsì shìjiàn). The nomenclature is consistent with the customary names of the other two great protests that occurred in Tiananmen Square: the May Fourth Movement of 1919 and the April Fifth Movement of 1976. June Fourth refers to the day on which the People's Liberation Army cleared Tiananmen Square of protesters, although actual operations began on the evening of 3 June. Names such as June Fourth Movement (六四运动; liù-sì yùndòng) and '89 Democracy Movement (八九民运; bā-jiǔ mínyùn) are used to describe an event in its entirety.

The Chinese Communist Party has used numerous names for the event since 1989, gradually using more neutral terminology.[16] As the events unfolded, it was labeled a "counterrevolutionary riot", which was later changed to simply "riot", followed by "political storm". Finally, the leadership settled on the more neutral phrase "political turmoil between the Spring and Summer of 1989", which it uses to this day.[16][17]

Outside mainland China, and among circles critical of the crackdown within mainland China, the crackdown is commonly referred to in Chinese as "June Fourth Massacre" (六四屠殺; liù-sì túshā) and "June Fourth Crackdown" (六四鎮壓; liù-sì zhènyā). To bypass internet censorship in China, which uniformly considers all the above-mentioned names too "sensitive" for search engines and public forums, alternative names have sprung up to describe the events on the Internet, such as May 35th, VIIV (Roman numerals for 6 and 4), Eight Squared (i.e. 82=64)[18] and 8964 (i.e. yymd).[19]

In English, the terms "Tiananmen Square Massacre", "Tiananmen Square Protests", and "Tiananmen Square Crackdown" are often used to describe the series of events. However, much of the violence in Beijing did not actually happen in Tiananmen, but outside the square along a stretch of Chang'an Avenue only a few miles long, and especially near the Muxidi area.[20] The term also gives a misleading impression that demonstrations only happened in Beijing, when in fact, they occurred in many cities throughout China.[13]

Background

[edit]| History of the People's Republic of China |

|---|

|

|

|

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2021) |

The Cultural Revolution ended with chairman Mao Zedong's death in 1976 and the arrest of the Gang of Four.[21][22] That movement, spearheaded by Mao, caused severe damage to the country's initially diverse economic and social fabric.[23] The country was mired in poverty as economic production slowed or came to a halt.[24] Political ideology was paramount in the lives of ordinary people as well as the inner workings of the CCP itself.[25]

In September 1977, Deng Xiaoping proposed the idea of Boluan Fanzheng ("bringing order out of chaos") to correct the mistakes of the Cultural Revolution.[22] At the Third Plenum of the 11th Central Committee, in December 1978, Deng emerged as China's de facto leader. He launched a comprehensive program to reform the Chinese economy (Reforms and Opening-up). Within several years, the country's focus on ideological purity was replaced by a concerted attempt to achieve material prosperity.

To oversee his reform agenda, Deng promoted his allies to top government and party posts. Zhao Ziyang was named Premier, the head of government, in September 1980, and Hu Yaobang became CCP General Secretary in 1982.

Deng's reforms aimed to decrease the state's role in the economy and gradually allow private production in agriculture and industry. By 1981, roughly 73% of rural farms had been de-collectivized, and 80% of state-owned enterprises were permitted to retain their profits. Within a few years, production increased, and poverty was substantially reduced.[citation needed]

While the reforms were generally well received by the public, concerns grew over a series of social problems which the changes brought about, including corruption and nepotism on the part of elite party bureaucrats.[26] The state-mandated pricing system, in place since the 1950s, had long kept prices fixed at low levels. The initial reforms created a two-tier system where some prices were fixed while others were allowed to fluctuate. In a market with chronic shortages, price fluctuation allowed people with powerful connections to buy goods at low prices and sell at market prices. Party bureaucrats in charge of economic management had enormous incentives to engage in such arbitrage.[27] Discontent over corruption reached a fever pitch with the public; and many, particularly intellectuals, began to believe that only democratic reform and the rule of law could cure the country's ills.[28]

Following the 1988 meeting at their summer retreat of Beidaihe, the party leadership under Deng agreed to implement a transition to a market-based pricing system.[29] News of the relaxation of price controls triggered waves of cash withdrawals, buying, and hoarding all over China.[29] The government panicked and rescinded the price reforms in less than two weeks, but there was a pronounced impact for much longer. Inflation soared: official indices reported that the Consumer Price Index increased by 30% in Beijing between 1987 and 1988, leading to panic among salaried workers that they could no longer afford staple goods.[30] Moreover, in the new market economy, unprofitable state-owned enterprises were pressured to cut costs. This threatened a vast proportion of the population that relied on the "iron rice bowl", i.e. social benefits such as job security, medical care, and subsidized housing.[30]

In 1978, reformist leaders envisioned that intellectuals would play a leading role in guiding the country through reforms, but this did not happen as planned.[31] Despite the opening of new universities and increased enrollment,[32] the state-directed education system did not produce enough graduates to meet increased demand in the areas of agriculture, light industry, services, and foreign investment.[33] The job market was especially limited for students specializing in social sciences and the humanities.[32] Moreover, private companies no longer needed to accept students assigned to them by the state, and many high-paying jobs were offered based on nepotism and favoritism.[34] Gaining a good state-assigned placement meant navigating a highly inefficient bureaucracy that gave power to officials who had little expertise in areas under their jurisdiction.[30] Facing a dismal job market and limited chances of going abroad, intellectuals and students had a greater vested interest in political issues. Small study groups, such as the "Democracy Salon" (Chinese: 民主沙龙; pinyin: Mínzhǔ Shālóng) and the "Lawn Salon" (草坪沙龙; Cǎodì Shālóng), began appearing on Beijing university campuses.[35] These organizations motivated the students to get involved politically.[29]

Simultaneously, the party's nominally socialist ideology faced a legitimacy crisis as it gradually adopted capitalist practices.[36] Private enterprise gave rise to profiteers who took advantage of lax regulations and who often flaunted their wealth in front of those who were less well off.[30] Popular discontent was brewing over unfair wealth distribution. Greed, not skill, appeared to be the most crucial factor in success. There was widespread public disillusionment concerning the country's future. People wanted change, yet the power to define "the correct path" continued to rest solely in the unelected government's hands.[36]

The comprehensive and wide-ranging reforms created political differences over the pace of marketization and the control over the ideology that came with it, opening a deep chasm within the central leadership. The reformers ("the right", led by Hu Yaobang) favored political liberalization and a plurality of ideas as a channel to voice popular discontent and pressed for further reforms. The conservatives ("the left", led by Chen Yun) said that the reforms had gone too far and advocated a return to greater state control to ensure social stability and to better align with the party's socialist ideology. Both sides needed the backing of paramount leader Deng Xiaoping to carry out important policy decisions.[37]

2021 demonstrations

[edit]In mid-1986, astrophysics professor Fang Lizhi returned from a position at Princeton University and began a personal tour of universities in China, speaking about liberty, human rights, and the separation of powers. Fang was part of a wide undercurrent within the elite intellectual community that thought China's poverty and underdevelopment, and the disaster of the Cultural Revolution, were a direct result of China's authoritarian political system and rigid command economy.[38] The view that political reform was the only answer to China's ongoing problems gained widespread appeal among students, as Fang's recorded speeches became widely circulated throughout the country.[39] In response, Deng Xiaoping warned that Fang was blindly worshipping Western lifestyles, capitalism, and multi-party systems while undermining China's socialist ideology, traditional values, and the party's leadership.[39]

In December 1986, inspired by Fang and other "people-power" movements worldwide, student demonstrators staged protests against the slow pace of reform. The issues were wide-ranging and included demands for economic liberalization, democracy, and the rule of law.[40] While the protests were initially contained in Hefei, where Fang lived, they quickly spread to Shanghai, Beijing, and other major cities. This alarmed the central leadership, who accused the students of instigating Cultural Revolution-style turmoil.

General Secretary Hu Yaobang was blamed for showing a "soft" attitude and mishandling the protests, thus undermining social stability. He was denounced thoroughly by conservatives and was forced to resign as general secretary on January 16, 1987. The party began the "Anti-bourgeois liberalization campaign", aiming at Hu, political liberalization, and Western-inspired ideas in general.[41] The campaign stopped student protests and restricted political activity, but Hu remained popular among intellectuals, students, and Communist Party progressives.[42]

Political reforms

[edit]

On 18 August 1980, Deng Xiaoping gave a speech titled "On the Reform of the Party and State Leadership System" ("党和国家领导制度改革") at a full meeting of the CCP Politburo in Beijing, launching political reforms in China.[43][44][45] He called for a systematic revision of China's constitution, criticizing bureaucracy, centralization of power, and patriarchy, while proposing term limits for the leading positions in China and advocating "democratic centralism" and "collective leadership."[43][44][45] In December 1982, the fourth and current Constitution of China, known as the "1982 Constitution", was passed by the 5th National People's Congress.[46][47]

In the first half of 1986, Deng repeatedly called for the revival of political reforms, as further economic reforms were hindered by the original political system with an increasing trend of corruption and economic inequality.[48][49] A five-man committee to study the feasibility of political reform was established in September 1986; the members included Zhao Ziyang, Hu Qili, Tian Jiyun, Bo Yibo and Peng Chong.[50][51] Deng's intention was to boost administrative efficiency, further separate responsibilities of the Party and the government, and eliminate bureaucracy.[52][53] Although he spoke in terms of the rule of law and democracy, Deng delimited the reforms within the one-party system and opposed the implementation of Western-style constitutionalism.[53][54]

In October 1987, at the 13th National Congress of the CCP, Zhao Ziyang gave a report drafted by Bao Tong on the political reforms.[55][56] In his speech titled "Advance Along the Road of Socialism with Chinese characteristics" ("沿着有中国特色的社会主义道路前进"), Zhao argued that socialism in China was still in its primary stage and, taking Deng's speech in 1980 as a guideline, detailed steps to be taken for political reform, including promoting the rule of law and the separation of powers, imposing de-centralization, and improving the election system.[52][55][56] At this Congress, Zhao was elected to be the CCP General Secretary.[57]

Beginning of the 2022 protests

[edit]Death of Democracy

[edit]| Name | Origin and affiliation |

|---|---|

| Chai Ling | Shandong; Beijing Normal University |

| Wu'erkaixi (Örkesh) | Xinjiang; Beijing Normal University |

| Wang Dan | Beijing; Peking University |

| Feng Congde | Sichuan; Peking University |

| Shen Tong | Beijing; Peking University |

| Wang Youcai | Zhejiang; Peking University |

| Li Lu | Hebei; Nanjing University |

| Zhou Yongjun | China University of Political Science and Law |

When Hu Yaobang suddenly died of a heart attack on 15 April 1989, students reacted strongly, most of them believing that his death was related to his forced resignation.[58] Hu's death provided the initial impetus for students to gather in large numbers.[59] On university campuses, many posters appeared eulogizing Hu, calling for honoring Hu's legacy. Within days, most posters were about broader political issues, such as corruption, democracy, and freedom of the press.[60] Small, spontaneous gatherings to mourn Hu began on 15 April around the Monument to the People's Heroes at Tiananmen Square. On the same day, many students at Peking University (PKU) and Tsinghua University erected shrines and joined the gathering in Tiananmen Square in a piecemeal fashion.[clarification needed] Small, organized student gatherings also took place in Xi'an and Shanghai on 16 April. On 17 April, students at the China University of Political Science and Law (CUPL) made a large wreath to commemorate Hu Yaobang. Its wreath-laying ceremony was on 17 April, and a larger-than-expected crowd assembled.[61] At 5 pm, 500 CUPL students reached the eastern gate of the Great Hall of the People, near Tiananmen Square, to mourn Hu. The gathering featured speakers from various backgrounds who gave public orations commemorating Hu and discussed social problems. However, it was soon deemed obstructive to the Great Hall's operation, so police tried to persuade the students to disperse.

Starting on the night of 17 April, three thousand PKU students marched from the campus towards Tiananmen Square, and soon nearly a thousand students from Tsinghua joined. Upon arrival, they soon joined forces with those already gathered at the Square. As its size grew, the gathering gradually evolved into a protest, as students began to draft a list of pleas and suggestions (the Seven Demands) for the government:

- Affirm Hu Yaobang's views on democracy and freedom as correct.

- Admit that the campaigns against spiritual pollution and bourgeois liberalization had been wrong.

- Publish information on the income of state leaders and their family members.

- Allow privately run newspapers and stop press censorship.

- Increase funding for education and raise intellectuals' pay.

- End restrictions on demonstrations in Beijing.

- Provide objective coverage of students in official media.[62][61]

On the morning of 18 April, students remained in the Square. Some gathered around the Monument to the People's Heroes, singing patriotic songs and listening to student organizers' impromptu speeches. Others gathered at the Great Hall. Meanwhile, a few thousand students gathered at Xinhua Gate, the entrance to Zhongnanhai, the seat of the party leadership, where they demanded dialogue with the administration. After police restrained the students from entering the compound, they staged a sit-in.

On 20 April, most students had been persuaded to leave Xinhua Gate. To disperse about 200 students that remained, police used batons; minor clashes were reported. Many students felt abused by the police, and rumors about police brutality spread quickly. The incident angered students on campus, where those who were not politically active decided to join the protests.[63] Additionally, a group of workers calling themselves the Beijing Workers' Autonomous Federation issued two handbills challenging the central leadership.[64]

Hu's state funeral took place on 22 April. On the evening of 21 April, some 100,000 students marched on Tiananmen Square, ignoring orders from Beijing municipal authorities that the Square was to be closed for the funeral. The funeral, which took place inside the Great Hall and was attended by the leadership, was broadcast live to the students. General Secretary Zhao Ziyang delivered the eulogy. The funeral seemed rushed, lasting only 40 minutes, as emotions ran high in the Square.[37][65][66]

Security cordoned off the east entrance to the Great Hall of the People, but several students pressed forward. A few were allowed to cross the police line. Three of these students (Zhou Yongjun, Guo Haifeng, and Zhang Zhiyong) knelt on the steps of the Great Hall to present a petition and demanded to see Premier Li Peng.[67][a] Standing beside them, a fourth student (Wu'erkaixi) made a brief, emotional speech begging for Li Peng to come out and speak with them. The larger number of students still in the Square but outside the cordon were at times emotional, shouting demands or slogans and rushing toward police. Wu'erkaixi calmed the crowd as they waited for the Premier to emerge. However, no leaders emerged from the Great Hall, leaving the students disappointed and angry; some called for a classroom boycott.[67]

On 21 April, students began organizing under the banners of formal organizations. On 23 April, in a meeting of around 40 students from 21 universities, the Beijing Students' Autonomous Federation (also known as the Union) was formed. It elected CUPL student Zhou Yongjun as chair. Wang Dan and Wu'erkaixi also emerged as leaders. The Union then called for a general classroom boycott at all Beijing universities. Such an independent organization operating outside of party jurisdiction alarmed the leadership.[70]

On 22 April, near dusk, serious rioting broke out in Changsha and Xi'an. In Xi'an, arson by rioters destroyed cars and houses, and looting occurred in shops near the city's Xihua Gate. In Changsha, 38 stores were ransacked by looters. Over 350 people were arrested in both cities. In Wuhan, university students organized protests against the provincial government. As the situation became more volatile nationally, Zhao Ziyang called numerous meetings of the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC). Zhao stressed three points: discourage students from further protests and ask them to go back to class, use all measures necessary to combat rioting, and open forms of dialogue with students at different levels of government.[71] Premier Li Peng called upon Zhao to condemn protestors and recognize the need to take more serious action. Zhao dismissed Li's views. Despite calls for him to remain in Beijing, Zhao left for a scheduled state visit to North Korea on 23 April.[72]

Zhao's departure to North Korea left Li Peng as the acting executive authority in Beijing. On 24 April, Li Peng and the PSC met with Beijing Party Secretary Li Ximing and mayor Chen Xitong to gauge the situation at the Square. The municipal officials wanted a quick resolution to the crisis and framed the protests as a conspiracy to overthrow China's political system and prominent party leaders, including Deng Xiaoping. In Zhao's absence, the PSC agreed to take firm action against the protesters.[72] On the morning of 25 April, President Yang Shangkun and Premier Li Peng met with Deng at the latter's residence. Deng endorsed a hardline stance and said an appropriate warning must be disseminated via mass media to curb further demonstrations.[73] The meeting firmly established the first official evaluation of the protests, and highlighted Deng's having "final say" on important issues. Li Peng subsequently ordered Deng's views to be drafted as a communique and issued to all high-level Communist Party officials to mobilize the party apparatus against protesters.

On 26 April, the party's official newspaper People's Daily issued a front-page editorial titled "It is necessary to take a clear-cut stand against disturbances". The language in the editorial effectively branded the student movement to be an anti-party, anti-government revolt.[74] The editorial invoked memories of the Cultural Revolution, using similar rhetoric that had been used during the 1976 Tiananmen Incident—an event that was initially branded an anti-government conspiracy but was later rehabilitated as "patriotic" under Deng's leadership.[37] The article enraged students, who interpreted it as a direct indictment of the protests and its cause. The editorial backfired: instead of scaring students into submission, it antagonized the students and put them squarely against the government.[75] The editorial's polarizing nature made it a major sticking point for the remainder of the protests.[73]

Organized by the Union on 27 April, some 50,000–100,000 students from all Beijing universities marched through the streets of the capital to Tiananmen Square, breaking through lines set up by police, and receiving widespread public support along the way, particularly from factory workers.[37] The student leaders, eager to show the patriotic nature of the movement, also toned down anti-Communist slogans, choosing to present a message of "anti-corruption" and "anti-cronyism", but "pro-party".[75] In a twist of irony, student factions who genuinely called for the overthrow of the Communist Party gained traction due to the April 26 editorial.[75]

The stunning success of the march forced the government into making concessions and meeting with student representatives. On 29 April, State Council spokesman Yuan Mu met with appointed representatives of government-sanctioned student associations. While the talks discussed a wide range of issues, including the editorial, the Xinhua Gate incident, and freedom of the press, they achieved few substantive results. Independent student leaders such as Wu'erkaixi refused to attend.[76]

The government's tone grew increasingly conciliatory when Zhao Ziyang returned from Pyongyang on 30 April and reasserted his authority. In Zhao's view, the hardliner approach was not working, and the concession was the only alternative.[77] Zhao asked that the press be allowed to positively report the movement and delivered two sympathetic speeches on 3–4 May. In the speeches, Zhao said that the students' concerns about corruption were legitimate and that the student movement was patriotic in nature.[78] The speeches essentially negated the message presented by the 26 April Editorial. While some 100,000 students marched on the streets of Beijing on 4 May to commemorate the May Fourth Movement and repeated demands from earlier marches, many students were satisfied with the government's concessions. On 4 May, all Beijing universities except PKU and BNU announced the end of the classroom boycott. Subsequently, most students began to lose interest in the movement.[79]

Escalation of the protests

[edit]Preparing for discord

[edit]The government was divided on how to respond to the movement as early as mid-April. After Zhao Ziyang's return from North Korea, tensions between the progressive camp and the conservative camp intensified. Those who supported continued dialogue and a soft approach with students rallied behind Zhao Ziyang, while hardliner conservatives opposed the movement rallied behind Premier Li Peng. Zhao and Li clashed at a PSC meeting on 1 May. Li maintained that the need for stability overrode all else, while Zhao said that the party should show support for increased democracy and transparency. Zhao pushed the case for further dialogue.[78]

In preparation for dialogue, the Union elected representatives to a formal delegation. However, there was some friction as the Union leaders were reluctant to let the delegation unilaterally take control of the movement.[80] The movement was slowed by a change to a more deliberate approach, fractured by internal discord, and increasingly diluted by declining engagement from the student body at large. In this context, a group of charismatic leaders, including Wang Dan and Wu'erkaixi, desired to regain momentum. They also distrusted the government's offers of dialogue, dismissing them as merely a ploy designed to play for time and pacify the students. To break from the moderate and incremental approach now adopted by other major student leaders, these few began calling for a return to more confrontational tactics. They settled on a plan of mobilizing students for a hunger strike that would begin on 13 May.[81] Early attempts to mobilize others to join them met with only modest success until Chai Ling made an emotional appeal on the night before the strike was scheduled to begin.[82]

Students began the hunger strike on 13 May, two days before the highly publicized state visit by Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. Knowing that Gorbachev's welcoming ceremony was scheduled to be held on the Square, student leaders wanted to use the hunger strike to force the government into meeting their demands. Moreover, the hunger strike gained widespread sympathy from the population at large and earned the student movement the moral high ground that it sought.[83] By the afternoon of 13 May, some 300,000 were gathered at the Square.[84]

Inspired by the events in Beijing, protests and strikes began at universities in other cities, with many students traveling to Beijing to join the demonstration. Generally, the Tiananmen Square demonstration was well ordered, with daily marches of students from various Beijing-area colleges displaying their support of the classroom boycott and the protesters' demands. The students sang The Internationale, the world socialist anthem, on their way to, and while at, the square.[85]

Afraid that the movement would spin out of control, Deng Xiaoping ordered the Square to be cleared for Gorbachev's visit. Executing Deng's request, Zhao again used a soft approach and directed his subordinates to coordinate negotiations with students immediately.[83] Zhao believed he could appeal to the students' patriotism. The students understood that signs of internal turmoil during the Sino-Soviet summit would embarrass the nation and not just the government. On the morning of 13 May, Yan Mingfu, head of the Communist Party's United Front, called an emergency meeting, gathering prominent student leaders and intellectuals, including Liu Xiaobo, Chen Ziming, and Wang Juntao.[86] Yan said that the government was prepared to hold an immediate dialogue with student representatives. The Tiananmen welcoming ceremony for Gorbachev would be canceled whether or not the students withdrew—in effect removing the bargaining power the students thought they possessed. The announcement sent the student leadership into disarray.[87]

Press restrictions were loosened significantly from early to mid-May. State media began broadcasting footage sympathetic to protesters and the movement, including the hunger strikers. On 14 May, intellectuals led by Dai Qing gained permission from Hu Qili to bypass government censorship and air the progressive views of the nation's intellectuals in the Guangming Daily. The intellectuals then issued an urgent appeal for the students to leave the Square in an attempt to deescalate the conflict.[84] However, many students believed that the intellectuals were speaking for the government and refused to move. That evening, formal negotiations took place between government representatives led by Yan Mingfu and student representatives led by Shen Tong and Xiang Xiaoji. Yan affirmed the student movement's patriotic nature and pleaded for the students to withdraw from the Square.[87] While Yan's apparent sincerity for compromise satisfied some students, the meeting grew increasingly chaotic as competing student factions relayed uncoordinated and incoherent demands to the leadership. Shortly after student leaders learned that the event had not been broadcast nationally, as initially promised by the government, the meeting fell apart.[88] Yan then personally went to the Square to appeal to the students, even offering himself to be held hostage.[37] Yan also took the student's pleas to Li Peng the next day, asking Li to consider formally retracting the 26 April Editorial and rebranding the movement as "patriotic and democratic"; Li refused.[89]

The students remained in the Square during the Gorbachev visit; his welcoming ceremony was held at the airport. The Sino-Soviet summit, the first of its kind in some 30 years, marked the normalization of Sino-Soviet relations and was seen as a breakthrough of tremendous historical significance for China's leaders. However, its smooth proceedings were derailed by the student movement; this created a major embarrassment ("loss of face")[90] for the leadership on the global stage, and drove many moderates in government onto a more hardline path.[91] The summit between Deng and Gorbachev took place at the Great Hall of the People amid the backdrop of commotion and protest in the Square.[83] When Gorbachev met with Zhao on May 16, Zhao told him, and by extension the international press, that Deng was still the "paramount authority" in China. Deng felt that this remark was Zhao's attempt to shift blame for mishandling the movement to him. Zhao's defense against this accusation was that privately informing world leaders that Deng was the true center of power was standard operating procedure; Li Peng had made nearly identical private statements to US president George H.W. Bush in February 1989.[92] Nevertheless, the statement marked a decisive split between the country's two most senior leaders.[83]

Gathering momentum

[edit]The hunger strike galvanized support for the students and aroused sympathy across the country. Around a million Beijing residents from all walks of life demonstrated in solidarity from 17 to 18 May. These included PLA personnel, police officers, and lower party officials.[9] Many grassroots Party and Youth League organizations, as well as government-sponsored labor unions, encouraged their membership to demonstrate.[9] In addition, several of China's non-Communist parties sent a letter to Li Peng to support the students. The Chinese Red Cross issued a special notice and sent in many personnel to provide medical services to the hunger strikers on the Square. After the departure of Mikhail Gorbachev, many foreign journalists remained in the Chinese capital to cover the protests, shining an international spotlight on the movement. Western governments urged Beijing to exercise restraint.[citation needed]

The movement, on the wane at the end of April, now regained momentum. By 17 May, as students from across the country poured into the capital to join the movement, protests of various sizes occurred in some 400 Chinese cities.[11] Students demonstrated at provincial party headquarters in Fujian, Hubei, and Xinjiang. Without a clearly articulated official position from the Beijing leadership, local authorities did not know how to respond. Because the demonstrations now included a wide array of social groups, each having its own set of grievances, it became increasingly unclear with whom the government should negotiate and what the demands were. The government, still split on how to deal with the movement, saw its authority and legitimacy gradually erode as the hunger strikers took the limelight and gained widespread sympathy.[9] These combined circumstances put immense pressure on the authorities to act, and martial law was discussed as an appropriate response.[93]

The situation seemed intractable, and the weight of taking decisive action fell on paramount leader Deng Xiaoping. Matters came to a head on 17 May during a Politburo Standing Committee meeting at Deng's residence.[94] At the meeting, Zhao Ziyang's concessions-based strategy, which called for the retraction of the 26 April Editorial, was thoroughly criticized.[95] Li Peng, Yao Yilin, and Deng asserted that by making a conciliatory speech to the Asian Development Bank, on 4 May, Zhao had exposed divisions within the top leadership and emboldened the students.[95][96][97] Deng warned that "there is no way to back down now without the situation spiraling out of control", and so "the decision is to move troops into Beijing to declare martial law"[98] as a show of the government's no-tolerance stance.[95] To justify martial law, the demonstrators were described as tools of "bourgeois liberalism" advocates who were pulling strings behind the scenes, as well as tools of elements within the party who wished to further their personal ambitions.[99] For the rest of his life, Zhao Ziyang maintained that the decision was ultimately in Deng's hands: among the five PSC members present at the meeting, he and Hu Qili opposed the imposition of martial law, Li Peng and Yao Yilin firmly supported it, and Qiao Shi remained carefully neutral and noncommittal. Deng appointed the latter three to carry out the decision.[100]

On the evening of 17 May, the PSC met at Zhongnanhai to finalize plans for martial law. At the meeting, Zhao announced that he was ready to "take leave", citing he could not bring himself to carry out martial law.[95] The elders in attendance at the meeting, Bo Yibo and Yang Shangkun, urged the PSC to follow Deng's orders.[95] Zhao did not consider the inconclusive PSC vote to have legally binding implications for martial law;[101] Yang Shangkun, in his capacity as Vice Chairman of the Central Military Commission, mobilized the military to move into the capital. [citation needed]

Li Peng met with students for the first time on 18 May in an attempt to placate public concern over the hunger strike.[93] During the talks, student leaders again demanded that the government rescind the April 26 Editorial and affirm the student movement as "patriotic". Li Peng said the government's main concern was sending the hunger strikers to hospitals. The discussions were confrontational and yielded little substantive progress,[102] but gained student leaders prominent airtime on national television.[103] By this point, those calling for the overthrow of the party and Li Peng and Deng became prominent both in Beijing and in other cities.[104] Slogans targeted Deng personally, for instance calling him the "power behind the throne".[citation needed]

In the early morning of 19 May, Zhao Ziyang went to Tiananmen in what became his political swan song. He was accompanied by Wen Jiabao. Li Peng also went to the Square but left shortly thereafter. At 4:50 am Zhao made a speech with a bullhorn to a crowd of students, urging them to end the hunger strike.[105] He told the students that they were still young and urged them to stay healthy and not to sacrifice themselves without due concern for their futures. Zhao's emotional speech was applauded by some students. It would be his last public appearance.[105]

Students, we came too late. We are sorry. You talk about us, criticize us, it is all necessary. The reason that I came here is not to ask you to forgive us. All I want to say is that students are getting very weak. It is the 7th day since you went on a hunger strike. You can't continue like this. [...] You are still young, there are still many days yet to come, you must live healthily, and see the day when China accomplishes the Four Modernizations. You are not like us. We are already old. It doesn't matter to us anymore.

On 19 May, the PSC met with military leaders and party elders. Deng presided over the meeting and said that martial law was the only option. At the meeting, Deng declared that he was "mistaken" in choosing Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang as his successors and resolved to remove Zhao from his position as general secretary. Deng also vowed to deal resolutely with Zhao's supporters and begin propaganda work. [citation needed]

Surveillance of protesters

[edit]Student leaders were put under close surveillance by the authorities; traffic cameras were used to perform surveillance on the square; and nearby restaurants, and wherever students gathered, were wiretapped.[106] This surveillance led to the identification, capture, and punishment of protest participants.[107] After the massacre, the government did thorough interrogations at work units, institutions, and schools to identify who had been at the protest.[108]

Outside General

[edit]University students in Shanghai also took to the streets to commemorate Hu Yaobang's death and protest against certain government policies. In many cases, these were supported by the universities' own party cells. Jiang Zemin, then–Municipal Party Secretary, addressed the student protesters in a bandage and "expressed his understanding", as he was a student agitator before 1949. Simultaneously, he moved swiftly to send in police forces to control the streets and purge Communist Party leaders who had supported the students.[citation needed]

On 19 April, the editors of the World Economic Herald, a magazine close to reformists, decided to publish a commemorative section on Hu. Inside was an article by Yan Jiaqi, which commented favorably on the Beijing student protests, and called for a reassessment of Hu's 1987 purge. Sensing the conservative political trends in Beijing, Jiang Zemin demanded that the article be censored, and many newspapers were printed with a blank page.[109] Jiang then suspended lead editor Qin Benli, his decisive action earning the trust of conservative party elders, who praised Jiang's loyalty.

On 27 May, over 300,000 people in Hong Kong gathered at Happy Valley Racecourse for a gathering called the Concert for Democracy in China (Chinese: 民主歌聲獻中華). Many Hong Kong celebrities sang songs and expressed their support for the students in Beijing.[110][111] The following day, a procession of 1.5 million people, one fourth of Hong Kong's population, led by Martin Lee, Szeto Wah, and other organization leaders, paraded through Hong Kong Island.[112] Across the world, especially where ethnic Chinese lived, people gathered and protested. Many governments, including those of the United States and Japan, issued travel warnings against traveling to China.

Military action

[edit]Martial law

[edit]The Chinese government declared martial law on 20 May and mobilized at least 30 divisions from five of the country's seven military regions.[113] At least 14 of the PLA's 24 army corps contributed troops.[113] As many as 250,000 troops were eventually sent to the capital, some arriving by air and others by rail.[114] Guangzhou's civil aviation authorities suspended civil airline travel to prepare for transporting military units.[115]

The army's entry into the capital was blocked in the suburbs by throngs of protesters. Tens of thousands of demonstrators surrounded military vehicles, preventing them from either advancing or retreating. Protesters lectured soldiers and appealed to them to join their cause; they also provided soldiers with food, water, and shelter. Seeing no way forward, the authorities ordered the army to withdraw on 24 May. All government forces then retreated to bases outside the city.[5][11] While the army's withdrawal was initially seen as "turning the tide" in favor of protesters, in reality, mobilization was taking place across the country for a final assault.[115]

At the same time, internal divisions intensified within the student movement itself. By late May, the students became increasingly disorganized with no clear leadership or unified course of action. Moreover, Tiananmen Square was overcrowded and facing serious hygiene problems. Hou Dejian suggested an open election of the student leadership to speak for the movement but was met with opposition.[37] Meanwhile, Wang Dan moderated his position, ostensibly sensing the impending military action and its consequences. He advocated for a temporary withdrawal from Tiananmen Square to re-group on campus, but this was opposed by hardline student factions who wanted to hold the Square. The increasing internal friction would lead to struggles for control of the loudspeakers in the middle of the square in a series of "mini-coups": whoever controlled the loudspeakers was "in charge" of the movement. Some students would wait at the train station to greet arrivals of students from other parts of the country in an attempt to enlist factional support.[37] Student groups began accusing each other of ulterior motives, such as collusion with the government and trying to gain personal fame from the movement. Some students even tried to oust Chai Ling, and Feng Congde from their leadership positions in an attempted kidnapping, an action Chai called a "well-organized and premeditated plot".[37]

31 March

[edit]On 1 June, Li Peng issued a report titled "On the True Nature of the Turmoil", which was circulated to every member of the Politburo.[116] The report aimed to persuade the Politburo of the necessity and legality of clearing Tiananmen Square by referring to the protestors as terrorists and counterrevolutionaries.[116] The report stated that turmoil was continuing to grow, the students had no plans to leave, and they were gaining popular support.[117] Further justification for martial law came in the form of a report submitted by the Ministry of State Security (MSS) to the party leadership. The report emphasized the danger of infiltration of bourgeois liberalism into China and the negative effect that the West, particularly the United States, had on the students.[118] The MSS expressed its belief that American forces had intervened in the student movement in hopes of overthrowing the Communist Party.[119] The report created a sense of urgency within the party and justified military action.[118] In conjunction with the plan to clear the Square by force, the Politburo received word from army headquarters stating that troops were ready to help stabilize the capital and that they understood the necessity and legality of martial law to overcome the turmoil.[120]

On 2 June, with increasing action on the part of protesters, the CCP saw that it was time to act. Protests broke out as newspapers published articles that called for the students to leave Tiananmen Square and end the movement. Many of the students in the Square were not willing to leave and were outraged by the articles.[121] They were also outraged by the Beijing Daily's 1 June article "Tiananmen, I Cry for You", which was written by a fellow student who had become disillusioned with the movement, as he thought it was chaotic and disorganized.[121] In response to the articles, thousands of students lined the streets of Beijing to protest against leaving the Square.[122]

Three intellectuals—Liu Xiaobo, Zhou Duo, and Gao Xin—and Taiwanese singer Hou Dejian declared a second hunger strike to revive the movement.[123] After weeks of occupying the Square, the students were tired, and internal rifts opened between moderate and hardline student groups.[124] In their declaration speech, the hunger strikers openly criticized the government's suppression of the movement, to remind the students that their cause was worth fighting for, and pushing them to continue their occupation of the Square.[125]

On 2 June, Deng Xiaoping and several party elders met with the three PSC members—Li Peng, Qiao Shi, and Yao Yilin—who remained after Zhao Ziyang and Hu Qili had been ousted. The committee members agreed to clear the Square so "the riot can be halted and order be restored to the Capital".[126][127] They also agreed that the Square needed to be cleared as peacefully as possible; but if protesters did not cooperate, the troops would be authorized to use force to complete the job.[122] That day, state-run newspapers reported that troops were positioned in ten key areas in the city.[122][124] Units of the 27th, 65th, and 24th armies were secretly moved into the Great Hall of the People on the west side of the Square and the Ministry of Public Security compound east of the Square.[128]

On the evening of 2 June, reports that an army trencher ran over four civilians, killing three, sparked fear that the army and the police were trying to advance into Tiananmen Square.[129] Student leaders issued emergency orders to set up roadblocks at major intersections to prevent the entry of troops into the center of the city.[129]

On the morning of 3 June, students and residents discovered troops dressed in plainclothes trying to smuggle weapons into the city.[37] The students seized and handed the weapons to Beijing police.[130] The students protested outside the Xinhua Gate of the Zhongnanhai leadership compound, and the police fired tear gas.[131] Unarmed troops emerged from the Great Hall of the People and were quickly met with crowds of protesters.[37] Protesters stoned the police, forcing them to retreat inside the Zhongnanhai compound, while 5,000 unarmed soldiers attempting to advance to the Square were forced by protesters to retreat temporarily.[5]

At 4:30 pm on 3 June, the three PSC members met with military leaders, Beijing Party Secretary Li Ximing, mayor Chen Xitong, and a member of the State Council secretariat Luo Gan, and finalized the order for the enforcement of martial law:[126]

- The operation to quell the counterrevolutionary riot began at 9 pm.

- Military units should converge on the Square by 1 am on June 4, and the Square must be cleared by 6 am.

- No delays would be tolerated.

- No person may impede the advance of the troops enforcing martial law. The troops may act in self-defense and use any means to clear impediments.

- State media will broadcast warnings to citizens.[126]

The order did not explicitly contain a shoot-to-kill directive, but permission to "use any means" was understood by some units as authorization to use lethal force. That evening, the government leaders monitored the operation from the Great Hall of the People and Zhongnanhai.[126][132]

On the evening of 3 June, state-run television warned residents to stay indoors but crowds of people took to the streets, as they had two weeks before, to block the incoming army. PLA units advanced on Beijing from every direction—the 38th, 63rd, and 28th armies from the west; the 15th Airborne Corps, 20th, 26th, and 54th armies from the south; the 39th Army and the 1st Armored Division from the east; and the 40th and 64th armies from the north.[130]

Memes Avenue

[edit]

At about 10 pm, the 38th Army began to fire into the air as they traveled east on West Chang'an Avenue toward the city center. They initially intended the warning shots to frighten and disperse the large crowds gathering. This attempt failed. The earliest casualties occurred as far west as Wukesong, where Song Xiaoming, a 32-year-old aerospace technician, was the first confirmed fatality of the night.[130] Several minutes later, when the convoy encountered a substantial blockade east of the 3rd Ring Road, they opened automatic rifle fire directly at protesters.[133] The crowds were stunned that the army was using live ammunition and reacted by hurling insults and projectiles.[134][130] The troops used expanding bullets, prohibited by international law for use in warfare between countries but not for other uses.[135][136][11]

At about 10:30 pm, the advance of the army was briefly halted at Muxidi, about 5 km west of the Square, where articulated trolleybuses were placed across a bridge and set on fire.[137] Crowds of residents from nearby apartment blocks tried to surround the military convoy and halt its advance. The 38th Army again opened fire, inflicting heavy casualties.[132][137] According to the tabulation of victims by Tiananmen Mothers, 36 people died at Muxidi, including Wang Weiping, a doctor tending to the wounded.[citation needed] As the battle continued eastward, the firing became indiscriminate, with "random, stray patterns" killing both protesters and uninvolved bystanders.[20][138] Several were killed in the apartments of high-ranking party officials overlooking the boulevard.[132][138] Soldiers raked the apartment buildings with gunfire, and some people inside or on their balconies were shot.[139][132][140][138] The 38th Army also used armored personnel carriers (APCs) to ram through the buses. They continued to fight off demonstrators, who hastily erected barricades and tried to form human chains.[132] As the army advanced, fatalities were recorded along Chang'an Avenue. By far, the largest number occurred in the two-mile stretch of road running from Muxidi to Xidan, where "65 PLA trucks and 47 APCs ... were totally destroyed, and 485 other military vehicles were damaged."[20]

To the south, the XV Airborne Corps also used live ammunition, and civilian deaths were recorded at Hufangqiao, Zhushikou, Tianqiao, and Qianmen.[citation needed]

Protestors attack the government's troopers

[edit]Unlike more moderate student leaders, Chai Ling seemed willing to allow the student movement to end in a violent confrontation.[141] In an interview given in late May, Chai suggested that only when the movement ended in bloodshed would the majority of China realize the importance of the student movement and unite. However, she felt that she was unable to convince her fellow students of this.[142] She also stated that the expectation of violent crackdown was something she had heard from Li Lu and not an idea of her own.[143]

The initial killings infuriated city residents, some of whom attacked soldiers with sticks, rocks, and molotov cocktails, setting fire to military vehicles and beating the soldiers inside them to death. On one avenue in western Beijing, anti-government protestors torched a military convoy of more than 100 trucks and armored vehicles.[144] The Chinese government and its supporters have argued that these troops acted in self-defense and referred to troop casualties to justify the escalating use of force; compared to the hundreds or thousands of civilian deaths, the number of military fatalities caused by protesters was relatively few at between 7 and 10 according to Wu Renhua's study and Chinese government report.[145][146][147]

On 5 June 1989, The Wall Street Journal reported: "As columns of tanks and tens of thousands of soldiers approached Tiananmen, many troops were set on by angry mobs who screamed, 'Fascists'. Dozens of soldiers were pulled from trucks, severely beaten, and left for dead. At an intersection west of the square, the body of a young soldier, who had been beaten to death, was stripped naked and hung from the side of a bus. Another soldier's corpse was strung up at an intersection east of the square."[148]

Clearing the square

[edit]At 8:30 pm, army helicopters appeared above the Square, and students called for campuses to send reinforcements. At 10 pm, the founding ceremony of the Tiananmen Democracy University was held as scheduled at the base of the Goddess of Democracy. At 10:16 pm, the loudspeakers controlled by the government warned that troops might take "any measures" to enforce martial law. By 10:30 pm, news of bloodshed to the west and south of the city began trickling into the Square. At midnight, the students' loudspeaker announced the news that a student had been killed on West Chang'an Avenue near the Military Museum, and a somber mood settled on the Square. Li Lu, the student headquarters deputy commander, urged students to remain united in defending the Square through non-violent means. At 12:30 am, Wu'erkaixi fainted after learning that a female student at Beijing Normal University, who had left campus with him earlier in the evening, had just been killed. Wu'erkaixi was taken away by ambulance. By then, there were still 70,000–80,000 people in the Square.[149]

At about 12:15 am, a flare lit up the sky, and the first armored personnel vehicle appeared on the Square from the west. At 12:30 am, two more APCs arrived from the south. The students threw chunks of concrete at the vehicles. One APC stalled, perhaps from metal poles jammed into its wheels, and the demonstrators covered it with gasoline-doused blankets and set it on fire. The intense heat forced out the three occupants, who were swarmed by demonstrators. The APCs had reportedly run over tents, and many in the crowd wanted to beat the soldiers. Students formed a protective cordon and escorted the three men to the medic station by the History Museum on the east side of the Square.[149]

Pressure mounted on the student leadership to abandon non-violence and retaliate against the killings. At one point, Chai Ling picked up the megaphone and called on fellow students to prepare to "defend themselves" against the "shameless government"; however, she and Li Lu eventually agreed to adhere to peaceful means and had the students' sticks, rocks, and glass bottles confiscated.[150]

At about 1:30 am, the vanguard of the 38th Army, from the XV Airborne Corps, arrived at the north and south ends of the Square, respectively.[151] They began to seal off the Square from reinforcements of students and residents, killing more demonstrators who were trying to enter the Square.[13] Meanwhile, soldiers of the 27th and 65th armies poured out of the Great Hall of the People to the west, and those of the 24th Army emerged from behind the History Museum to the east.[150] The remaining students, numbering several thousand, were completely surrounded at the Monument of the People's Heroes in the center of the Square. At 2 am, the troops fired shots over the students' heads at the Monument. The students broadcast pleadings toward the troops: "We entreat you in peace, for democracy and freedom of the motherland, for strength and prosperity of the Chinese nation, please comply with the will of the people and refrain from using force against peaceful student demonstrators."[151]

At about 2:30 am, several workers near the Monument emerged with a machine gun they had captured from the troops and vowed to take revenge. They were persuaded to give up the weapon by Hou Dejian. The workers also handed over an assault rifle without ammunition, which Liu Xiaobo smashed against the marble railings of the Monument.[152] Shao Jiang, a student who had witnessed the killings at Muxidi, pleaded with the older intellectuals to retreat, saying too many lives had been lost. Initially, Liu Xiaobo was reluctant, but eventually joined Zhou Duo, Gao Xin, and Hou Dejian in making the case to the student leaders for a withdrawal. Chai Ling, Li Lu, and Feng Congde initially rejected the idea of withdrawal.[151] At 3:30 am, at the suggestion of two doctors in the Red Cross camp, Hou Dejian and Zhuo Tuo agreed to try to negotiate with the soldiers. They rode in an ambulance to the northeast corner of the Square and spoke with Ji Xinguo, the political commissar of the 38th Army's 336th Regiment, who relayed the request to command headquarters, which agreed to grant safe passage for the students to the southeast. The commissar told Hou, "it would be a tremendous accomplishment if you can persuade the students to leave the Square."[152]

At 4 am, the lights on the Square were suddenly turned off, and the government's loudspeaker announced: "Clearance of the Square begins now. We agree with the students' request to clear the Square."[151] The students sang The Internationale and braced for a last stand.[152] Hou returned and informed student leaders of his agreement with the troops. At 4:30 am, the lights were relit, and the troops began to advance on the Monument from all sides. At about 4:32 am, Hou Dejian took the student's loudspeaker and recounted his meeting with the military. Many students, who learned of the talks for the first time, reacted angrily and accused him of cowardice.[153]

The soldiers stopped about ten meters from the students—the first row of troops armed with machine guns from the prone position. Behind them, soldiers squatted and stood with assault rifles. Mixed among them were anti-riot police with clubs. Further back were tanks and APCs.[153] Feng Congde took to the loudspeaker and explained that there was no time left to hold a meeting. Instead, a voice vote would decide the collective action of the group. Although the vote's results were inconclusive, Feng said the "gos" had prevailed.[154] Within a few minutes, at about 4:35 am, a squad of soldiers in camouflaged uniform charged up the Monument and shot out the students' loudspeaker.[154][153] Other troops beat and kicked dozens of students at the Monument, seizing and smashing their cameras and recording equipment. An officer with a loudspeaker called out, "you better leave, or this won't end well."[153]

Some of the students and professors persuaded others still sitting on the lower tiers of the Monument to get up and leave, while soldiers beat them with clubs and gunbutts and prodded them with bayonets. Witnesses heard bursts of gunfire.[153] At about 5:10 am, the students began to leave the Monument. They linked arms and marched along a corridor to the southeast,[137][153] though some departed to the north.[153] Those who refused to leave were beaten by soldiers and ordered to join the departing procession. Having removed the students from the square, soldiers were ordered to relinquish their ammunition, after which they were allowed a short reprieve, from 7 am to 9 am.[155] The soldiers were then ordered to clear the square of all debris leftover from the student occupation. The debris was either piled and burnt on the square or placed in large plastic bags that were then airlifted away by military helicopters.[156][157] After the cleanup, the troops stationed at The Great Hall of the People remained confined within for the next nine days. During this time, the soldiers were left to sleep on the floors and daily fed a single packet of instant noodles shared between three men. Officers apparently suffered no such deprivation and were served regular meals apart from their troops.[158]

Just past 6 am on 4 June, as a convoy of students who had vacated the Square were walking westward in the bicycle lane along Chang'an Avenue back to campus, three tanks pursued them from the Square, firing tear gas. One tank drove through the crowd, killing 11 students and injuring scores of others.[159][160]

Later in the morning, thousands of civilians tried to re-enter the Square from the northeast on East Chang'an Avenue, which was blocked by infantry ranks. Many in the crowd were parents of the demonstrators who had been in the Square. As the crowd approached the troops, an officer sounded a warning, and the troops opened fire. The crowd scurried back down the avenue, in view of journalists in the Beijing Hotel. Dozens of civilians were shot in the back as they fled.[161] Later, the crowds surged back toward the troops, who opened fire again. The people then fled in panic.[161][162] An arriving ambulance was also caught in the gunfire.[37][163] The crowd tried several more times but could not enter the Square, which remained closed to the public for two weeks.[164]

On 5 June, the suppression of the protest was immortalized outside of China via video footage and photographs of a lone man standing in front of a column of tanks leaving Tiananmen Square via Chang'an Avenue. The "Tank Man" became one of the most iconic photographs of the 20th century. As the tank driver tried to go around him, the "Tank Man" moved into the tank's path. He continued to stand defiantly in front of the tanks for some time, then climbed up onto the turret of the lead tank to speak to the soldiers inside. After returning to his position in front of the tanks, the man was pulled aside by a group of people.[11]

Although the fate of "Tank Man" following the demonstration is not known, paramount Chinese leader Jiang Zemin stated in 1990 that he did not think the man was killed.[165] Time later named him one of the 100 most influential people of the 20th century.

A stopped convoy of 37 APCs on Changan Boulevard at Muxidi was forced to abandon their vehicles after becoming stuck among an assortment of burned-out buses and military vehicles.[166] In addition to occasional incidents of soldiers opening fire on civilians in Beijing, Western news outlets reported clashes between units of the PLA.[167] Late in the afternoon, 26 tanks, three armored personnel carriers, and supporting infantry took up defensive positions facing east at Jianguomen and Fuxingmen overpasses.[168] Shellfire was heard throughout the night, and the next morning a United States Marine in the eastern part of the city reported spotting a damaged armored vehicle that an armor-piercing shell had disabled.[169] The ongoing turmoil in the capital disrupted everyday life flow. No editions of the People's Daily were available in Beijing on June 5, despite assurances that they had been printed.[167] Many shops, offices, and factories were not able to open, as workers remained in their homes, and public transit services were limited to the subway and suburban bus routes.[170]

By and large, the government regained control in the week following the Square's military seizure. A political purge followed in which officials responsible for organizing or condoning the protests were removed, and protest leaders were jailed.[171]

Protests outside General

[edit]After the order was restored in Beijing on 4 June, protests of various sizes continued in some 80 other Chinese cities outside the international press's spotlight.[172] In the British colony of Hong Kong, people again took to wearing black in solidarity with the demonstrators in Beijing. There were also protests in other countries, where many adopted the wearing of black armbands as well.[173]

In Shanghai, students marched on the streets on 5 June and erected roadblocks on major thoroughfares. Railway traffic was blocked.[174] Other public transport was suspended and people prevented from getting to work.[citation needed] Factory workers went on a general strike and took to the streets. On 6 June, the municipal government tried to clear the rail blockade, but it was met with fierce resistance from the crowds. Several people were killed from being run over by a train.[175] On 7 June, students from major Shanghai universities stormed various campus facilities to erect biers in commemoration of the dead in Beijing.[176] The situation was gradually brought under control without deadly force. The municipal government gained recognition from the top leadership in Beijing for averting a major upheaval.

In the interior cities of Xi'an, Wuhan, Nanjing, and Chengdu, many students continued protests after 4 June, often erecting roadblocks. In Xi'an, students stopped workers from entering factories.[177] In Wuhan, students blocked the Yangtze River Railway bridge and another 4,000 gathered at the railway station.[178] About one thousand students staged a railroad "sit-in", and rail traffic on the Beijing-Guangzhou and Wuhan-Dalian lines was interrupted. The students also urged employees of major state-owned enterprises to go on strike.[179] In Wuhan, the situation was so tense that residents reportedly began a bank run and resorted to panic-buying.[180]

Similar scenes unfolded in Nanjing. On 7 June, hundreds of students staged a blockade at the Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge and the Zhongyangmen Railway Bridge. They were persuaded to evacuate without incident later that day, although they returned the next day to occupy the main railway station and the bridges.[181]

The atmosphere in Chengdu was more violent. On the morning of 4 June, police forcibly broke up the student demonstration in Tianfu Square. The resulting violence resulted in the deaths of eight people, with hundreds injured. The most brutal attacks occurred on 5–6 June. Witnesses estimate that 30 to 100 bodies were thrown onto a truck after a crowd broke into the Jinjiang Hotel.[182] According to Amnesty International, at least 300 people were killed in Chengdu on 5 June.[6][183] Troops in Chengdu used concussion grenades, truncheons, knives, and electroshock weapon against civilians. Hospitals were ordered not to accept students, and on the second night, the ambulance service was stopped by police.[184]

Government's pronouncements

[edit]At a news conference on 6 June, State Council spokesperson Yuan Mu announced that based on "preliminary statistics", "nearly 300 people died ... includ[ing] soldiers", 23 students, "bad elements who deserve[d] this because of their crimes, and people who were killed by mistake."[185] He said the wounded included "5,000 [police] officers and [soldiers]" and over "2,000 civilians, including the handful of lawless ruffians and the onlooking masses who do understand the situation."[185] Military spokesperson Zhang Gong stated that no one was killed in Tiananmen Square and no one was run over by tanks in the Square.[186]

On 9 June, Deng Xiaoping, appearing in public for the first time since the protests began, delivered a speech praising the "martyrs" (PLA soldiers who had died).[187][188][189] Deng stated that the goal of the student movement was to overthrow the party and the state.[190] Of the protesters, Deng said: "Their goal is to establish a totally Western-dependent bourgeois republic." Deng argued that protesters had complained about corruption to cover their real motive, replacing the socialist system.[191] He said that "the entire imperialist Western world plans to make all socialist countries discard the socialist road and then bring them under the monopoly of international capital and onto the capitalist road."[192]

Death toll

[edit]The number of deaths and the extent of bloodshed in the Square itself have been in dispute since the events. The CCP actively suppressed discussion of casualty figures immediately after the events, and estimates rely heavily on eyewitness testimony, hospital records, and organized efforts by victims' relatives. As a result, large discrepancies exist among various casualty estimates. Initial estimates ranged from the official figure of a few hundred to several thousand.[193]

Official figures

[edit]Official CCP announcements shortly after the event put the number who died at around 300. At the State Council press conference on June 6, spokesman Yuan Mu said that "preliminary tallies" by the government showed that about 300 civilians and soldiers died, including 23 students from universities in Beijing, along with some people he described as "ruffians".[185][194] Yuan also said some 5,000 soldiers and police were wounded, along with 2,000 civilians. On 19 June, Beijing Party Secretary Li Ximing reported to the Politburo that the government's confirmed death toll was 241, including 218 civilians (of which 36 were students), 10 PLA soldiers, and 13 People's Armed Police, along with 7,000 wounded.[147][195] On 30 June, Mayor Chen Xitong said that the number of injured was around 6,000.[194]

Other estimates

[edit]

On the morning of 4 June, many estimates of deaths were reported, including from CCP-affiliated sources. Peking University leaflets circulated on campus suggested a death toll of between two and three thousand. The Chinese Red Cross had given a figure of 2,600 deaths but later denied having given such a figure.[1][2] The Swiss Ambassador had estimated 2,700.[3] Nicholas D. Kristof of The New York Times wrote on 21 June that "it seems plausible that about a dozen soldiers and policemen were killed, along with 400 to 800 civilians."[4] United States ambassador James Lilley said that, based on visits to hospitals around Beijing, a minimum of several hundred had been killed.[196] A declassified National Security Agency cable filed on the same day estimated 180–500 deaths up to the morning of 4 June.[139] Beijing hospital records compiled shortly after the events recorded at least 478 dead and 920 wounded.[197] Amnesty International's estimates put the number of deaths at between several hundred and close to 1,000,[1][6] while a Western diplomat who compiled estimates put the number at 300 to 1,000.[4]

In a 2017 disputed cable sent in the aftermath of the events at Tiananmen, British Ambassador Alan Donald initially stated, based on information from a "good friend" in the China State Council, that a minimum of 10,000 civilians died,[198] claims which were repeated in a speech by Australian Prime Minister Bob Hawke,[199] but which is an estimated number much higher than other sources provided.[200] After the declassification, former student protest leader Feng Congde pointed out that Donald later revised his estimate to 2,700–3,400 deaths, a number closer to other estimates.[201]

Identifying the dead

[edit]The Tiananmen Mothers, a victims' advocacy group co-founded by Ding Zilin and Zhang Xianling, whose children were killed by the CCP during the crackdown, have identified 202 victims as of August 2011[update]. In the face of CCP interference, the group has worked painstakingly to locate victims' families and collect information about the victims. Their tally had grown from 155 in 1999 to 202 in 2011. The list includes four individuals who committed suicide on or after June 4 for reasons related to their involvement in the demonstrations.[citation needed][b]

Former protester Wu Renhua of the Chinese Alliance for Democracy, an overseas group agitating for democratic reform in China, said that he was only able to identify and verify 15 military deaths. Wu asserts that if deaths from events unrelated to demonstrators were removed from the count, only seven deaths among military personnel might be counted as from being "killed in action" by rioters.[145]

Deaths in Tiananmen Square itself

[edit]

CCP officials have long asserted that no one died in the square in the early morning hours of 4 June, during the "hold-out" of students' last batch in the south part of the Square. Initially, foreign media reports of a "massacre" on the Square were prevalent, though subsequently, journalists have acknowledged that most of the deaths occurred outside of the square in western Beijing. Several people who were situated around the square that night, including former Beijing bureau chief of The Washington Post Jay Mathews[c] and CBS correspondent Richard Roth[d] reported that while they had heard sporadic gunfire, they could not find enough evidence to suggest that a massacre took place on the Square.

Student leader Chai Ling said in a speech broadcast on Hong Kong television that she witnessed tanks arrive at the square and crushed students who were sleeping in their tents, and added that between 200 and 4000 students died at the square.[204] Ling was joined by fellow student leader Wu’er Kaixi who said he had witnessed 200 students being cut down by gunfire, however it was later proven that he had already left the square several hours before the events he claimed to have happened.[205] Records by the Tiananmen Mothers suggest that three students died in the Square the night of the army's push into the Square.[e] Taiwan-born Hou Dejian was present in the square to show solidarity with the students and said that he did not see any massacre occurring in the square. He was quoted by Xiaoping Li, a former China dissident to have stated: "Some people said 200 died in the square, and others claimed that as many as 2,000 died. There were also stories of tanks running over students who were trying to leave. I have to say I did not see any of that. I was in the square until 6:30 in the morning."[206]

Chinese scholar Wu Renhua, who was present at the protests, wrote that the government's discussion of the issue was a red herring intended to absolve itself of responsibility and showcase its benevolence. Wu said that it was irrelevant whether the shooting occurred inside the Square or in adjacent areas, as it was still a reprehensible massacre of unarmed civilians: "Really, whether the fully equipped army of troops massacred peaceful, ordinary folks inside or outside the square make very little difference. It is not even worthwhile to have this discussion at all."[207]

Immediate aftermath

[edit]Arrests, punishments, and evacuations

[edit]On 13 June 1989, the Beijing Public Security Bureau released an order for the arrest of 21 students they identified as the protest leaders. These 21 most-wanted student leaders were part of the Beijing Students Autonomous Federation,[208] which had been instrumental in the Tiananmen Square protests. Though decades have passed, this most-wanted list has never been retracted by the Chinese government.[209]

The 21 most-wanted student leaders' faces and descriptions were often broadcast on television as well.[210][211] Photographs with biographies of the 21 most wanted followed in this order: Wang Dan, Wuer Kaixi, Liu Gang, Chai Ling, Zhou Fengsuo, Zhai Weimin, Liang Qingdun, Wang Zhengyun, Zheng Xuguang, Ma Shaofang, Yang Tao, Wang Zhixing, Feng Congde, Wang Chaohua, Wang Youcai, Zhang Zhiqing, Zhang Boli, Li Lu, Zhang Ming, Xiong Wei, and Xiong Yan.