User:Orser67/Pierce

The presidency of Franklin Pierce began on March 4, 1853 and ended on March 4, 1857. The 14th President of the United States, Franklin Pierce was a northern Democrat who saw the abolitionist movement as a fundamental threat to the unity of the nation.[1] His polarizing actions in championing and signing the Kansas–Nebraska Act and enforcing the Fugitive Slave Act alienated anti-slavery groups while failing to stem intersectional conflict, setting the stage for Southern secession and the American Civil War. Pierce was succeeded by Democrat James Buchanan.

Seen by Democrats as a compromise candidate uniting northern and southern interests, he was nominated on the 49th ballot of the 1852 Democratic National Convention. In the 1852 presidential election, Pierce and his running mate William R. King easily defeated the Whig ticket of Winfield Scott and William A. Graham. As president, Pierce simultaneously attempted to enforce neutral standards for civil service while also satisfying the diverse elements of the Democratic Party with patronage, an effort which largely failed and turned many in his party against him. Pierce was a Young America expansionist presided over the Gadsden Purchase of land from Mexico and led a failed attempt to acquire Cuba from Spain. He signed trade treaties with the United Kingdom and Japan, while his Cabinet reformed their departments and improved accountability, but these successes were overshadowed by political strife during his presidency.

His popularity in the Northern states declined sharply after he supported the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which nullified the Missouri Compromise, though many whites in the South continued to support him. Passage of the act led to violent conflict over the expansion of slavery in the American West. Pierce's administration was further damaged when several of his diplomats issued the Ostend Manifesto, calling for the annexation of Cuba, a document which was roundly criticized. Although Pierce fully expected to be renominated by the Democrats in the 1856 presidential election, he was abandoned by his party in favor of Buchanan. Historians and other scholars generally rank Pierce as among the worst of US Presidents.

Election of 1852

[edit]

As the 1852 presidential election approached, the Democrats were divided by the slavery issue, though most of the "Barnburners" who had left the party in 1848 with Martin Van Buren had returned. It was widely expected that the 1852 Democratic National Convention would result in deadlock, with no major candidate able to win the necessary two-thirds majority. New Hampshire Democrats felt that, as the state in which their party had most consistently gained Democratic majorities, they should supply the presidential candidate. Other possible standard-bearers included Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, James Buchanan of Pennsylvania, Lewis Cass of Michigan, William Marcy of New York, Sam Houston of Texas, and Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri.[2] Pierce quietly allowed his supporters to lobby for him, with the understanding that his name would not be entered at the convention unless it was clear none of the front-runners could win. To broaden his potential base of southern support as the convention approached, he wrote letters reiterating his support for the Compromise of 1850, including the controversial Fugitive Slave Act.[3]

The convention assembled on June 1 in Baltimore, Maryland, and the deadlock occurred as expected. The first ballot was taken on June 3. Of 288 delegates, Cass claimed 116, Buchanan 93, and the rest were scattered, without a single vote for Pierce. The next 34 ballots passed with no-one near victory, and still no votes for Pierce. The Buchanan team decided to have their delegates vote for minor candidates, including Pierce, to demonstrate that no one but Buchanan could win. It was hoped that once delegates realized this, the convention would unite behind Buchanan. This novel tactic backfired after several ballots as Virginia, New Hampshire, and Maine switched to Pierce; the remaining Buchanan forces began to break for Marcy, and before long Pierce was in third place. After the 48th ballot, North Carolina Congressman James C. Dobbin delivered an unexpected and passionate endorsement of Pierce, sparking a wave of support for the dark horse candidate. On the 49th ballot, Pierce received all but six of the votes, and thus gained the Democratic nomination for president. Delegates selected Alabama Senator William R. King, a Buchanan supporter, as Pierce's running mate, and adopted a party platform that rejected further "agitation" over the slavery issue and supported the Compromise of 1850.[4]

Rejecting incumbent President Millard Fillmore, the Whigs nominated General Winfield Scott, whom Pierce had served under in Mexico. The Whigs could not unify their factions as the Democrats had, and the convention adopted a platform almost indistinguishable from that of the Democrats, including support of the Compromise of 1850. This incited the Free Soilers to field their own candidate, Senator Hale of New Hampshire, at the expense of the Whigs. The lack of political differences reduced the campaign to a bitter personality contest and helped to dampen voter turnout in the election to its lowest level since 1836; it was, according to Pierce biographer Peter A. Wallner, "one of the least exciting campaigns in presidential history".[5] Scott was harmed by the lack of enthusiasm of anti-slavery northern Whigs for the candidate and platform; New-York Tribune editor Horace Greeley summed up the attitude of many when he said of the Whig platform, "we defy it, execrate it, spit upon it".[6]

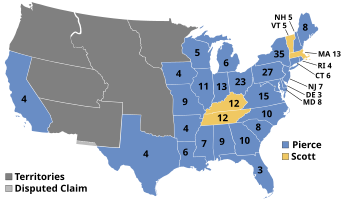

Pierce kept quiet so as not to upset his party's delicate unity, and allowed his allies to run the campaign. It was the custom at the time for candidates to not appear to seek the office, and he did no personal campaigning.[7] Pierce's opponents caricatured him as an anti-Catholic coward and alcoholic ("the hero of many a well-fought bottle").[8] Scott, meanwhile, drew weak support from the Whigs, who were torn by their pro-Compromise platform and found him to be an abysmal, gaffe-prone public speaker.[9] The Democrats were confident: a popular slogan was that the Democrats "will pierce their enemies in 1852 as they poked [that is, Polked] them in 1844."[10] This proved to be true, as Scott won only Kentucky, Tennessee, Massachusetts and Vermont, finishing with 42 electoral votes to Pierce's 254. With 3.2 million votes cast, Pierce won the popular vote with 50.9 to 44.1 percent. A sizable block of Free Soilers broke for Pierce's in-state rival, Hale, who won 4.9 percent of the popular vote.[11] In the concurrent Congressional elections, the Democrats increased their majorities in both houses of Congress.[12]

Tragedy and transition

[edit]Pierce began his presidency in mourning. Weeks after his election, on January 6, 1853, the President-elect's family had been traveling from Boston by train when their car derailed and rolled down an embankment near Andover, Massachusetts. Pierce and Jane survived, but in the wreckage found their only remaining son, 11-year-old Benjamin, crushed to death, his body nearly decapitated. Pierce was not able to hide the gruesome sight from Jane. They both suffered severe depression afterward, which likely affected Pierce's performance as president.[13] Jane wondered if the train accident was divine punishment for her husband's pursuit and acceptance of high office. She wrote a lengthy letter of apology to "Benny" for her failings as a mother.[14] Jane would avoid social functions for much of her first two years as First Lady, making her public debut in that role to great sympathy at the public reception held at the White House on New Year's Day, 1855.[15]

Jane remained in New Hampshire as Pierce departed for his inauguration, which she did not attend. Pierce, the youngest man to be elected president to that point, chose to affirm his oath of office on a law book rather than swear it on a Bible, as all his predecessors except John Quincy Adams had done. He was the first president to deliver his inaugural address from memory.[16] In the address he hailed an era of peace and prosperity at home and urged a vigorous assertion of U.S. interests in its foreign relations, including the "eminently important" acquisition of new territories. "The policy of my Administration", said the new president, "will not be deterred by any timid forebodings of evil from expansion." Avoiding the word "slavery", he emphasized his desire to put the "important subject" to rest and maintain a peaceful union. He alluded to his own personal tragedy, telling the crowd, "You have summoned me in my weakness, you must sustain me by your strength."[17]

Administration and appointments

[edit]Executive branch

[edit]| The Pierce cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Franklin Pierce | 1853–1857 |

| Vice President | William R. King | 1853 |

| None | 1853–1857 | |

| Secretary of State | William L. Marcy | 1853–1857 |

| Secretary of the Treasury | James Guthrie | 1853–1857 |

| Secretary of War | Jefferson Davis | 1853–1857 |

| Attorney General | Caleb Cushing | 1853–1857 |

| Postmaster General | James Campbell | 1853–1857 |

| Secretary of the Navy | James C. Dobbin | 1853–1857 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Robert McClelland | 1853–1857 |

In his Cabinet appointments, Pierce sought to unite a party that was squabbling over the fruits of victory. Most of the party had not originally supported him for the nomination, and some had allied with the Free Soil party to gain victory in local elections. Pierce decided to allow each of the party's factions some appointments, even those that had not supported the Compromise of 1850.[18]

All of Pierce's cabinet nominations were confirmed unanimously and immediately by the Senate.[19] Pierce spent the first few weeks of his term sorting through hundreds of lower-level federal positions to be filled. This was a chore, as he sought to represent all factions of the party, and could fully satisfy none of them. Partisans found themselves unable to secure positions for their friends, which put the Democratic Party on edge and fueled bitterness between factions. Before long, northern newspapers accused Pierce of filling his government with pro-slavery secessionists, while southern newspapers accused him of abolitionism.[19]

Factionalism between the pro- and anti-administration Democrats ramped up quickly, especially within the New York Democratic Party. The more conservative Hardshell Democrats or "Hards" of New York were deeply skeptical of the Pierce administration, which was associated with Secretary of State William L. Marcy and the more moderate New York faction, the Softshell Democrats or "Softs".[20]

Pierce's running mate William R. King was severely ill with tuberculosis, and after the election he went to Cuba to recuperate. His condition deteriorated, and Congress passed a special law, allowing him to be sworn in before the American consul in Havana on March 24. Wanting to die at home, he returned to his plantation in Alabama on April 17 and died the next day. The office of vice president remained vacant for the remainder of Pierce's term, as the Constitution then had no provision for filling the vacancy, making the Senate President pro tempore, initially David Atchison of Missouri, next in line to the presidency.[21]

Pierce sought to run a more efficient and accountable government than his predecessors.[22] His Cabinet members implemented an early system of civil service examinations which was a forerunner to the Pendleton Act passed three decades later.[23] The Interior Department was reformed by Secretary Robert McClelland, who systematized its operations, expanded the use of paper records, and pursued fraud.[24] Another of Pierce's reforms was to expand the role of the U.S. attorney general in appointing federal judges and attorneys, which was an important step in the eventual development of the Justice Department.[22] There was a vacancy on the Supreme Court—Fillmore, having failed to get Senate confirmation for his nominees, had offered it to newly elected Louisiana Senator Judah P. Benjamin, who had declined. Pierce also offered the seat to Benjamin, and when the Louisianan persisted in his refusal,[25] nominated instead John Archibald Campbell, an advocate of states' rights; this would be Pierce's only Supreme Court appointment.[26]

Judicial appointments

[edit]Pierce appointed John Archibald Campbell to the Supreme Court of the United States. John McKinley's death in 1852 had created a vacancy on the court during the tenure of President Millard Fillmore. Fillmore made several nominations to fill the vacancy before the end of his term, but his nominees were denied confirmation by the Senate. After Pierce took office, he quickly nominated Campbell, who won the approval of the Senate. Campbell would remain on the court until the Battle of Fort Sumter in 1861, and he was later appointed as Confederate Assistant Secretary of War.

Pierce also appointed three judges to the United States circuit courts and twelve judges to the United States district courts. He was the first president to appoint judges to the United States Court of Claims.

Economic policy and internal improvements

[edit]

Pierce charged Treasury Secretary James Guthrie with reforming the Treasury, which was inefficiently managed and had many unsettled accounts. Guthrie increased oversight of Treasury employees and tariff collectors, many of whom were withholding money from the government. Despite laws requiring funds to be held in the Treasury, large deposits remained in private banks under the Whig administrations. Guthrie reclaimed these funds and sought to prosecute corrupt officials, with mixed success.[27]

Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, at Pierce's request, led surveys with the Corps of Topographical Engineers of possible transcontinental railroad routes throughout the country. The Democratic Party had long rejected federal appropriations for internal improvements, but Davis felt that such a project could be justified as a Constitutional national security objective. Davis also deployed the Army Corps of Engineers to supervise construction projects in the District of Columbia, including the expansion of the United States Capitol and building of the Washington Monument.[28]

Foreign and military affairs

[edit]The Pierce administration fell in line with the expansionist Young America movement, with William L. Marcy leading the charge as Secretary of State. Marcy sought to present to the world a distinctively American, republican image. He issued a circular recommending that U.S. diplomats wear "the simple dress of an American citizen" instead of the elaborate diplomatic uniforms worn in the courts of Europe, and that they only hire American citizens to work in consulates.[29] Marcy received international praise for his 73-page letter defending Austrian refugee Martin Koszta, who had been captured abroad in mid-1853 by the Austrian government despite his intention to become a U.S. citizen.[30]

Secretary of War Davis, an advocate of a southern transcontinental route, persuaded Pierce to send rail magnate James Gadsden to Mexico to buy land for a potential railroad. Gadsden was also charged with re-negotiating the provisions of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo which required the U.S. to prevent Native American raids into Mexico from New Mexico Territory. Gadsden negotiated a treaty with Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna in December 1853, purchasing a large swath of land to America's southwest. Negotiations were nearly derailed by William Walker's unauthorized expedition into Mexico, and so a clause was included charging the U.S. with combating future such attempts.[31] Congress reduced the Gadsden Purchase to the region now comprising southern Arizona and part of southern New Mexico; the price was cut from $15 million to $10 million. Congress also included a protection clause for a private citizen, Albert G. Sloo, whose interests were threatened by the purchase. Pierce opposed the use of the federal government to prop up private industry and did not endorse the final version of the treaty, which was ratified nonetheless.[32] The acquisition brought the contiguous United States to its present-day boundaries, excepting later minor adjustments.[33]

Relations with the United Kingdom were tense, as American fishermen felt menaced by the British navy's increasing enforcement of Canadian waters. Marcy completed a trade reciprocity agreement with British minister to Washington, John Crampton, which would reduce the need for aggressive coastline enforcement. Buchanan was sent as minister to London to pressure the British government, which was slow to support a new treaty. A favorable reciprocity treaty was ratified in August 1854, which Pierce saw as a first step towards the American annexation of Canada.[34] While the administration negotiated with Britain over the Canada–US border, U.S. interests were also threatened in Central America, where the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty of 1850 had failed to keep Great Britain from expanding its influence. Gaining the advantage over Britain in the region was a key part of Pierce's expansionist goals.[35]

British consuls in the United States sought to enlist Americans for the Crimean War in 1854, in violation of neutrality laws, and Pierce eventually expelled minister Crampton and three consuls. To the President's surprise, the British did not expel Buchanan in retaliation. In his December 1855 message to Congress Pierce had set forth the American case that Britain had violated the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty. The British, according to Buchanan, were impressed by the message and were rethinking their policy. Nevertheless, Buchanan was not successful in getting the British to renounce their Central American possessions. The Canadian treaty was ratified by Congress, the British Parliament, and by the colonial legislatures in Canada.[36]

Pierce's administration aroused sectional apprehensions when three U.S. diplomats in Europe drafted a proposal to the president to purchase Cuba from Spain for $120 million (USD), and justify the "wresting" of it from Spain if the offer were refused. The publication of the Ostend Manifesto, which had been drawn up at the insistence of Secretary of State Marcy, provoked the scorn of northerners who viewed it as an attempt to annex a slave-holding possession to bolster Southern interests. It helped discredit the expansionist policy of Manifest Destiny the Democratic Party had often supported.[37]

Pierce favored expansion and a substantial reorganization of the military. Secretary of War Davis and Navy Secretary James C. Dobbin found the Army and Navy in poor condition, with insufficient forces, a reluctance to adopt new technology, and inefficient management.[38] Under the Pierce administration, Commodore Matthew C. Perry visited Japan (a venture originally planned under Fillmore) in an effort to expand trade to the East. Perry wanted to encroach on Asia by force, but Pierce and Dobbin pushed him to remain diplomatic. Perry signed a modest trade treaty with the Japanese shogunate which was successfully ratified.[39] The 1856 launch of the USS Merrimac, one of six newly commissioned steam frigates, was one of Pierce's "most personally satisfying" days in office.[40]

Bleeding Kansas

[edit]

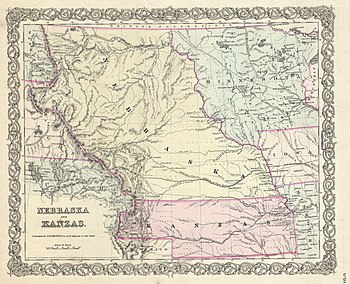

The greatest challenge to the country's equilibrium during the Pierce administration was the passage of the Kansas–Nebraska Act. Organizing the largely unsettled Nebraska Territory, which stretched from Missouri to the Rocky Mountains, and from Texas north to what is now the Canada–US border, was a crucial part of Douglas's plans for western expansion. He wanted a transcontinental railroad with a link from Chicago to California, through the vast western territory. Organizing the territory was necessary for settlement as the land would not be surveyed nor put up for sale until a territorial government was authorized. Those from slave states had never been content with western limits on slavery, and felt it should be able to expand into territories procured with blood and treasure that had come, in part, from the South. Douglas and his allies planned to organize the territory and let local settlers decide whether to allow slavery. This would repeal the Missouri Compromise of 1820, as most of it was north of the 36°30′ N line the Missouri Compromise deemed "free". The territory would be split into a northern part, Nebraska, and a southern part, Kansas, and the expectation was that Kansas would allow slavery and Nebraska would not.[41] In the view of pro-slavery Southern politicians, the Compromise of 1850 had already annulled the Missouri Compromise by admitting the state of California, including territory south of the compromise line, as a free state.[42]

Pierce had wanted to organize the Nebraska Territory without explicitly addressing the matter of slavery, but Douglas could not get enough southern support to accomplish this.[43] Pierce was skeptical of the bill, knowing it would result in bitter opposition from the North. Douglas and Davis convinced him to support the bill regardless. It was tenaciously opposed by northerners such as Ohio Senator Salmon P. Chase and Massachusetts' Charles Sumner, who rallied public sentiment in the North against the bill. Northerners had been suspicious of the Gadsden Purchase, moves towards Cuba annexation, and the influence of slaveholding Cabinet members such as Davis, and saw the Nebraska bill as part of a pattern of southern aggression. The result was a political firestorm that did great damage to Pierce's presidency.[41]

Pierce and his administration used threats and promises to keep most Democrats on board in favor of the bill. The Whigs split along sectional lines; the conflict destroyed them as a national party. The Kansas–Nebraska Act was passed in May 1854 and would come to define the Pierce presidency. The political turmoil that followed the passage saw the short-term rise of the nativist and anti-Catholic American Party, often called the Know Nothings, and the founding of the Republican Party.[41]

Even as the act was being debated, settlers on both sides of the slavery issue poured into the territories so as to secure the outcome they wanted in the voting. The passage of the act resulted in so much violence between groups that the territory became known as Bleeding Kansas. Thousands of pro-slavery Border Ruffians came across from Missouri to vote in the territorial elections although they were not resident in Kansas, giving that element the victory. Pierce supported the outcome despite the irregularities. When Free-Staters set up a shadow government, and drafted the Topeka Constitution, Pierce called their work an act of rebellion. The president continued to recognize the pro-slavery legislature, which was dominated by Democrats, even after a Congressional investigative committee found its election to have been illegitimate. He dispatched federal troops to break up a meeting of the Topeka government.[45]

Passage of the act coincided with the seizure of escaped slave Anthony Burns in Boston. Northerners rallied in support of Burns, but Pierce was determined to follow the Fugitive Slave Act to the letter, and dispatched federal troops to enforce Burns' return to his Virginia owner despite furious crowds.[46]

Elections during the Pierce presidency

[edit]Mid-term election of 1854

[edit]The midterm congressional elections of 1854 and 1855 were devastating to the Democrats, despite the collapse of the Whig Party. The Democrats lost almost every state outside the South, as the administration's opponents in the North worked together to return opposition members to Congress.[44] Northern Whigs splintered among several parties, with the anti-slavery Republican Party and the nativist American Party (the formal name of the Know Nothings) emerging as the two strongest competitors to the Democratic Party.[47] In Pierce's New Hampshire, hitherto loyal to the Democratic Party, the Know-Nothings elected the governor, all three representatives, dominated the legislature, and returned John P. Hale to the Senate.[44] Nathaniel Banks, a member of the American Party and the Free Soil Party, won election as Speaker of the House after a protracted battle.[48]

Election of 1856 and transition

[edit]Pierce fully expected to be renominated by the Democrats. In reality his chances of winning the nomination were slim, let alone re-election. The administration was widely disliked in the North for its position on the Kansas–Nebraska Act, and Democratic leaders were aware of Pierce's electoral vulnerability. Nevertheless, his supporters began to plan for an alliance with Douglas to deny James Buchanan the nomination. Buchanan had solid political connections and had been safely overseas through most of Pierce's term, leaving him untainted by the Kansas debacle.[49]

When balloting began on June 5 at the convention in Cincinnati, Ohio, Pierce expected a plurality, if not the required two-thirds majority. On the first ballot, he received only 122 votes, many of them from the South, to Buchanan's 135, with Douglas and Cass receiving the rest. By the following morning fourteen ballots had been completed, but none of the three main candidates were able to get two-thirds of the vote. Pierce, whose support had been slowly declining as the ballots passed, directed his supporters to break for Douglas, withdrawing his name in a last-ditch effort to defeat Buchanan. Douglas, only 43 years of age, believed that he could be nominated in 1860 if he let the older Buchanan win this time, and received assurances from Buchanan's managers that this would be the case. After two more deadlocked ballots, Douglas's managers withdrew his name, leaving Buchanan as the clear winner. To soften the blow to Pierce, the convention issued a resolution of "unqualified approbation" in praise of his administration and selected his ally, former Kentucky Representative John C. Breckinridge, as the vice-presidential nominee.[49] This loss marked the only time in U.S. history that an elected president who was an active candidate for reelection was not nominated for a second term.[50]

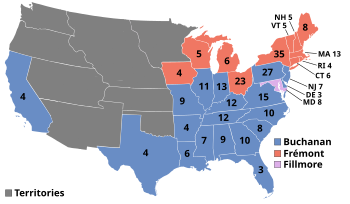

Pierce endorsed Buchanan, though the two remained distant; he hoped to resolve the Kansas situation by November to improve the Democrats' chances in the general election. He installed John W. Geary as territorial governor, who drew the ire of pro-slavery legislators.[51] Geary was able to restore order in Kansas, though the electoral damage had already been done—Republicans used "Bleeding Kansas" and "Bleeding Sumner" (the brutal caning of Charles Sumner by South Carolina Representative Preston Brooks in the Senate chamber) as election slogans.[52] The Buchanan/Breckinridge ticket was elected, but the Democratic percentage of the popular vote in the North fell from 49.8 percent in 1852 to 41.4 in 1856 as Buchanan won only five of sixteen free states (Pierce had won fourteen), and in three of those, Buchanan won because of a split between the Republican candidate, former California senator John C. Frémont and the Know Nothing, former president Fillmore.[53]

Pierce did not temper his rhetoric after losing the nomination. In his final message to Congress, delivered in December 1856, he vigorously attacked Republicans and abolitionists. He took the opportunity to defend his record on fiscal policy, and on achieving peaceful relations with other nations.[54] In the final days of the Pierce administration, Congress passed bills to increase the pay of army officers and to build new naval vessels, also expanding the number of seamen enlisted. It also passed a tariff reduction bill he had long sought.[55] Pierce and his cabinet left office on March 4, 1857, the only time in U.S. history that the original cabinet members all remained for a full four-year term.[56]

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Rumsch, BreAnn (2009). Franklin Pierce:14th President of the United States. Edina, Minnesota: ABDO Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-60453-469-6.

- ^ Wallner (2004), pp. 181–84; Gara (1991), pp, 23–29.

- ^ Wallner (2004), pp. 184–97; Gara (1991), pp. 32–33.

- ^ Wallner (2004), pp. 197–202; Gara (1991), pp. 33–34.

- ^ Wallner (2004), pp. 210–13; Gara (1991), pp. 36–38. Quote from Gara, 38.

- ^ Holt (2010), loc. 724.

- ^ Wallner (2004), p. 231; Gara (1991), p. 38, Holt (2010), loc. 725.

- ^ Wallner (2004), p. 206; Gara (1991), p. 38.

- ^ Gara (1991), p. 38.

- ^ Wallner (2004), p. 203.

- ^ Wallner (2004), pp. 229–30; Gara (1991), p. 39.

- ^ Holt (2010), loc. 740.

- ^ Wallner (2004), pp. 241–49; Gara (1991), pp. 43–44.

- ^ Wallner (2004), pp. 241–49.

- ^ Boulard (2006), p. 55.

- ^ Hurja, Emil (1933). History of Presidential Inaugurations. New York Democrat. p. 49.

- ^ Wallner (2004), pp. 249–55.

- ^ Holt, loc. 767.

- ^ a b Wallner (2007), pp. 5–24.

- ^ Wallner (2007), pp. 15–18, and throughout.

- ^ Wallner (2007), pp. p. 21–22.

- ^ a b Wallner (2007), p. 20.

- ^ Wallner (2007), pp. 35–36.

- ^ Wallner (2007), pp. 36–39.

- ^ Butler (1908), pp. 118–19.

- ^ Wallner (2007), p. 10.

- ^ Wallner (2007), pp. 32–36.

- ^ Wallner (2007), pp. 40–41, 52.

- ^ Wallner (2007), pp. 25–32; Gara (1991), p. 128.

- ^ Wallner (2007), pp. 61–63; Gara (1991), pp. 128–29.

- ^ Wallner (2007), pp. 75–81; Gara (1991), pp. 129–33.

- ^ Wallner (2007), pp. 106–08; Gara (1991), pp. 129–33.

- ^ Holt, loc. 872.

- ^ Wallner (2007), pp. 27–30, 63–66, 125–26; Gara (1991), p. 133.

- ^ Wallner (2007), pp. 26–27; Gara (1991), pp. 139–40.

- ^ Holt (2010), loc. 902–17.

- ^ Wallner (2007), pp. 131–57; Gara (1991), pp. 149–55.

- ^ Wallner (2007), pp. 40–43.

- ^ Wallner (2007), p. 172; Gara (1991), pp. 134–35.

- ^ Wallner (2007), p. 256.

- ^ a b c Wallner (2007), pp. 90–102, 119–22; Gara (1991), pp. 88–100, Holt (2010), loc. 1097–1240.

- ^ Jefferson Davis, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government at p. 25.

- ^ Etchison, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Wallner (2007), pp. 158–67; Gara (1991), pp. 99–100.

- ^ Wallner (2007), pp. 195–209; Gara (1991), pp. 111–20.

- ^ Wallner (2007), pp. 122–25; Gara (1991), pp. 107–09.

- ^ Holt, Michael F. (10 March 2016). "Are the Republicans Going the Way of the Whigs?". University of Virginia Center for Politics. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ Glass, Andrew (3 December 2012). "The House speaker bog-down, Dec. 3, 1855". Politico. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- ^ a b Wallner (2007), pp. 266–70; Gara (1991), pp. 157–67, Holt (2010), loc. 1515–58.

- ^ Rudin, Ken (July 22, 2009). "When Has A President Been Denied His Party's Nomination?". NPR. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- ^ Wallner (2007), pp. 272–80.

- ^ Holt (2010), loc. 1610.

- ^ Holt (2010), loc. 1610–24.

- ^ Wallner (2007), pp. 292–96; Gara (1991), pp. 177–79.

- ^ Wallner (2007), pp. 303–04.

- ^ Wallner (2007), p. 305.

Sources

[edit]- Boulard, Garry (2006). The Expatriation of Franklin Pierce: The Story of a President and the Civil War. iUniverse, Inc. ISBN 0-595-40367-0.

- Butler, Pierce (1908). Judah P. Benjamin. American Crisis Biographies. George W. Jacobs & Company. OCLC 664335.

- Etchison, Nicole (2004). Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-1287-4.

- Gara, Larry (1991). The Presidency of Franklin Pierce. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0494-4.

- Holt, Michael F. (2010). Franklin Pierce. The American Presidents (Kindle ed.). Henry Holt and Company, LLC. ISBN 978-0-8050-8719-2.

- Wallner, Peter A. (2004). Franklin Pierce: New Hampshire's Favorite Son. Plaidswede. ISBN 0-9755216-1-6.

- Wallner, Peter A. (2007). Franklin Pierce: Martyr for the Union. Plaidswede. ISBN 978-0-9790784-2-2.

Further reading

[edit]- Allen, Felicity (1999). Jefferson Davis, Unconquerable Heart. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0-8262-1219-0.

- Barlett, D.W. (1852). The life of Gen. Frank. Pierce, of New Hampshire, the Democratic candidate for president of the United States. Derby & Miller. OCLC 1742614.

- Bergen, Anthony (May 30, 2015). "In Concord: The Friendship of Pierce and Hawthorne". Medium.

- Brinkley, A; Dyer, D (2004). The American Presidency. Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-618-38273-9.

- Hawthorne, Nathaniel (1852). The Life of Franklin Pierce. Ticknor, Reed and Fields. OCLC 60713500.

- Nichols, Roy Franklin (1923). The Democratic Machine, 1850–1854. Columbia University Press. OCLC 2512393.

- Nichols, Roy Franklin (1931). Franklin Pierce, Young Hickory of the Granite Hills. University of Pennsylvania Press. OCLC 426247.

- Potter, David M. (1976). The Impending Crisis, 1848–1861. Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-013403-8.

- Silbey, Joel H. (2014). A Companion to the Antebellum Presidents 1837–1861. Wiley. pp 345–96

- Taylor, Michael J.C. (2001). "Governing the Devil in Hell: 'Bleeding Kansas' and the Destruction of the Franklin Pierce Presidency (1854–1856)". White House Studies. 1: 185–205.

External links

[edit]- Works by Franklin Pierce at Project Gutenberg

- Essays on Franklin Pierce and shorter essays on each member of his cabinet and First Lady, from the Miller Center of Public Affairs

- Error in Template:Internet Archive author: Orser67/Pierce doesn't exist.

- Franklin Pierce: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- Biography from the White House

- Franklin Pierce Bicentennial

- "Life Portrait of Franklin Pierce", from C-SPAN's American Presidents: Life Portraits, June 14, 1999

- "Franklin Pierce: New Hampshire's Favorite Son"—Booknotes interview with Peter Wallner, November 28, 2004

- Franklin Pierce Personal Manuscripts