User:Ncinquino/sandbox

| Adrenal insufficiency | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adrenal gland | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

Adrenal insufficiency is a condition in which the adrenal glands do not produce adequate amounts of steroid hormones, primarily cortisol; but may also include impaired production of aldosterone (a mineralocorticoid), which regulates sodium conservation, potassium secretion, and water retention.[1][2] Craving for salt or salty foods due to the urinary losses of sodium is common.[3]

Addison's disease and congenital adrenal hyperplasia can manifest as adrenal insufficiency. If not treated, adrenal insufficiency may result in severe abdominal pains, vomiting, profound muscle weakness and fatigue, depression, extremely low blood pressure (hypotension), weight loss, kidney failure, changes in mood and personality, and shock (adrenal crisis).[4] An adrenal crisis often occurs if the body is subjected to stress, such as an accident, injury, surgery, or severe infection; death may quickly follow.[4]

Adrenal insufficiency can also occur when the hypothalamus or the pituitary gland does not make adequate amounts of the hormones that assist in regulating adrenal function.[1][5][6] This is called secondary or tertiary adrenal insufficiency and is caused by lack of production of ACTH in the pituitary or lack of CRH in the hypothalamus, respectively.[7]

Types

[edit]There are three major types of adrenal insufficiency.

- Primary adrenal insufficiency is due to impairment of the adrenal glands.

- 80% are due to an autoimmune disease called Addison's disease or autoimmune adrenalitis.

- One subtype is called idiopathic, meaning of unknown cause.

- Other cases are due to congenital adrenal hyperplasia or an adenoma (tumor) of the adrenal gland.

- Secondary adrenal insufficiency is caused by impairment of the pituitary gland or hypothalamus.[8] Its principal causes include pituitary adenoma (which can suppress production of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and lead to adrenal deficiency unless the endogenous hormones are replaced); and Sheehan's syndrome, which is associated with impairment of only the pituitary gland.

- Tertiary adrenal insufficiency is due to hypothalamic disease and a decrease in the release of corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH).[9] Causes can include brain tumors and sudden withdrawal from long-term exogenous steroid use (which is the most common cause overall).[10]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Signs and symptoms include hypoglycemia, dehydration, weight loss, and disorientation. Additional signs and symptoms include weakness, tiredness, dizziness, low blood pressure that falls further when standing (orthostatic hypotension), cardiovascular collapse, muscle aches, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. These problems may develop gradually and insidiously. Addison's disease can present with tanning of the skin that may be patchy or even all over the body. Characteristic sites of tanning are skin creases (e.g. of the hands) and the inside of the cheek (buccal mucosa). Goitre and vitiligo may also be present.[4] Eosinophilia may also occur.[11] Because of salt loss, craving of salty foods is also common. In women, menstrual periods may become irregular or stop. Because symtpoms progress slowly, they are usually ignored until a stressful event like an illness or an accident causes them to become worse. This is called acute adrenal insufficiency, or an addisonian crisis.

Causes

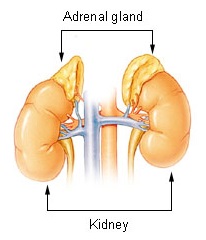

[edit]Adrenal insufficiency occurs when the adrenal glands don’t make or produce enough of the hormone cortisol. Humans have 2 adrenal glands, located just above the kidneys. The adrenal glands work with the hypothalamus and pituitary glands in the brain. Cortisol functions to break down fats, proteins, and carbohydrates in the body. It also controls blood pressure and is involved in the immune system function.[12]

As previously mentioned, there are 2 types of adrenal insufficiency, primary and secondary. Primary adrenal insufficiency is most often caused by autoimmune conditions, when one’s own immune system attacks their healthy adrenal glands (adrenal cortex, specifically) by mistake. For chronic adrenal insufficiency, the major contributors are autoimmune adrenalitis (Addison's Disease), tuberculosis, AIDS, and metastatic disease.[13] Minor causes of chronic adrenal insufficiency are systemic amyloidosis, fungal infections, hemochromatosis, and sarcoidosis.[13] Autoimmune adrenalitis may be part of Type 2 autoimmune polyglandular syndrome, which can include type 1 diabetes, hyperthyroidism, and autoimmune thyroid disease (also known as autoimmune thyroiditis, Hashimoto's thyroiditis, and Hashimoto's disease).[14] Hypogonadism may also present with this syndrome. Other diseases that are more common in people with autoimmune adrenalitis include premature ovarian failure, celiac disease, and autoimmune gastritis with pernicious anemia.[15]

Acute adrenal insufficiency is mainly caused by a sudden withdrawal of long-term corticosteroid therapy, Waterhouse–Friderichsen syndrome, and stress in people with underlying chronic adrenal insufficiency.[13] The latter is termed critical illness–related corticosteroid insufficiency.

Adrenoleukodystrophy can also cause adrenal insufficiency.[16]

Adrenal insufficiency can also result when a patient has a craniopharyngioma, which is a histologically benign tumor that can damage the pituitary gland and so cause the adrenal glands not to function. This would be an example of secondary adrenal insufficiency syndrome.

As briefly touched on, other causes for primary adrenal insufficiency include cancer, fungal infections, tuberculosis infection of the adrenal glands, or inherited disorders of the endocrine glands.

Lack of hormone ACTH can lead to secondary adrenal insufficiency.[17] This can occur with long term steroid use (in treatment of a secondary health condition). For example, those with asthma or rheumatoid arthritis may use prednisone daily, and thus are susceptible to the development of secondary adrenal insufficiency. Other causes of secondary adrenal insufficiency include pituitary gland tumor, loss of blood flow to the pituitary gland, removal of the pituitary gland or exposure to radiation treatment, partial hypothalamic removal.

Causes of adrenal insufficiency can be categorized by the mechanism through which they cause the adrenal glands to produce insufficient cortisol. These are adrenal dysgenesis (the gland has not formed adequately during development), impaired steroidogenesis (the gland is present but is biochemically unable to produce cortisol) or adrenal destruction (disease processes leading to glandular damage).[18]

Corticosteroid withdrawal

[edit]Use of high-dose steroids for more than a week begins to produce suppression of the person's adrenal glands because the exogenous glucocorticoids suppress release of hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and pituitary adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). With prolonged suppression, the adrenal glands atrophy (physically shrink), and can take months to recover full function after discontinuation of the exogenous glucocorticoid. During this recovery time, the person is vulnerable to adrenal insufficiency during times of stress, such as illness, due to both adrenal atrophy and suppression of CRH and ACTH release.[19][20] Use of steroids joint injections may also result in adrenal suppression after discontinuation.[21]

Adrenal dysgenesis

[edit]All causes in this category are genetic, and generally very rare. These include mutations to the SF1 transcription factor, congenital adrenal hypoplasia due to DAX-1 gene mutations and mutations to the ACTH receptor gene (or related genes, such as in the Triple A or Allgrove syndrome). DAX-1 mutations may cluster in a syndrome with glycerol kinase deficiency with a number of other symptoms when DAX-1 is deleted together with a number of other genes.[18]

Impaired steroidogenesis

[edit]To form cortisol, the adrenal gland requires cholesterol, which is then converted biochemically into steroid hormones. Interruptions in the delivery of cholesterol include Smith–Lemli–Opitz syndrome and abetalipoproteinemia.

Of the synthesis problems, congenital adrenal hyperplasia is the most common (in various forms: 21-hydroxylase, 17α-hydroxylase, 11β-hydroxylase and 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase), lipoid CAH due to deficiency of StAR and mitochondrial DNA mutations.[18] Some medications interfere with steroid synthesis enzymes (e.g. ketoconazole), while others accelerate the normal breakdown of hormones by the liver (e.g. rifampicin, phenytoin).[18]

Adrenal destruction

[edit]Autoimmune adrenalitis is the most common cause of Addison's disease in the industrialised world. Autoimmune destruction of the adrenal cortex is caused by an immune reaction against the enzyme 21-hydroxylase (a phenomenon first described in 1992).[22] This may be isolated or in the context of autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome (APS type 1 or 2), in which other hormone-producing organs, such as the thyroid and pancreas, may also be affected.[23]

Adrenal destruction is also a feature of adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD), and when the adrenal glands are involved in metastasis (seeding of cancer cells from elsewhere in the body, especially lung), hemorrhage (e.g. in Waterhouse–Friderichsen syndrome or antiphospholipid syndrome), particular infections (tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis), or the deposition of abnormal protein in amyloidosis.[24]

Pathophysiology

[edit]The specific pathophysiology of adrenal insufficiency depends on the etiology, or cause of the condition. In most forms of primary adrenal insufficiency (autoimmune), the patient has antibodies that attack the various enzymes in the adrenal cortex (though cell-mediated mechanisms also contribute).

Secondary adrenal insufficiency refers to decreased adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation of the adrenal cortex and therefore does not affect the aldosterone levels. Traumatic brain injury and panhypopituitarism are common causes.

Tertiary adrenal insufficiency refers to decreased hypothalamic stimulation of the pituitary to secrete ACTH. Exogenous steroid administration is the most common cause of tertiary adrenal insufficiency. Surgery to correct Cushing disease can also lead to tertiary adrenal insufficiency.[25]

The other forms of adrenal insufficiency usually relate to destruction by infectious agents, or infiltration by metastatic malignant cells. Hemorrhagic infarction occurs due to sepsis with certain organisms (Neisseria species, tuberculosis, fungal infections, Streptococcus species, Staphylococcus species) or due to adrenal vein thrombosis. Death associated with adrenal insufficiency is usually of septic shock, hypotension, or cardiac arrhythmias.

Hyponatremia can be caused by glucocorticoid deficiency. Low levels of glucocorticoids leads to systemic hypotension (one of the effects of cortisol is to increase peripheral resistance), which results in a decrease in stretch of the arterial baroreceptors of the carotid sinus and the aortic arch. This removes the tonic vagal and glossopharyngeal inhibition on the central release of ADH: high levels of ADH will ensue, which will subsequently lead to increase in water retention and hyponatremia.[25]

Differently from mineralocorticoid deficiency, glucocorticoid deficiency does not cause a negative sodium balance (in fact a positive sodium balance may occur).[26]

Diagnosis

[edit]Adrenal insufficiency can be difficult to diagnose. A physician will begin by asking about medical history and about any obvious symptoms. Tests that measure the levels of cortisol and aldosterone are used to make a definite diagnosis and include the following:

ACTH Stimulation test is the most specific test for diagnosing adrenal insufficiency. Blood cortisol levels are measured before and after a synthetic form of adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH), a hormone secreted from the anterior pituitary, is given by injection.

Insulin-induced hypoglycemia test is used to determine how the hypothalamus, pituitary and adrenal glands respond to stress. During this test, blood is drawn to measure the blood glucose and cortisol levels, followed by an injection of fast-acting insulin. Blood glucose and cortisol levels are measured again 30, 45 and 90 minutes after the insulin injection. The normal response is for blood glucose levels to fall (this represents the stress) and cortisol levels to rise (response to stress)[27].

Once a diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency has been made, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen may be taken to see if the adrenal glands are diminished in size, reflecting destruction, or enlarged, reflecting infiltration by some independent disease process. The scan may also show signs of calcium deposits, which may indicate previous exposure to tuberculosis. A tuberculin skin test may be used to address the latter possibility.

A number of imaging tools may be used to examine the size and shape of the pituitary gland. The most common is the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, which produces a series of images that provide a cross-sectional picture of the pituitary and the area of the brain that surrounds it.

In addition, the function of the pituitary and its ability to produce other hormones are tested. Typically, measurements of ACTH- the pituitary hormone most relevant for maintenance of normal adrenal function- along with thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH) and prolactin are made under resting conditions following provocative simulation, such as following the administration of corticotrophin releasing hormone (CRH), which leads to an increase in ACTH levels under normal conditions.

As aforementioned, the best diagnostic tool to confirm adrenal insufficiency is the ACTH stimulation test; however, if a patient is suspected to be suffering from an acute adrenal crisis, immediate treatment with IV corticosteroids is imperative and should not be delayed for any testing, as the patient's health can deteriorate rapidly and result in death without replacing the corticosteroids.[28]

Dexamethasone should be used as the corticosteroid if the plan is to do the ACTH stimulation test at a later time as it is the only corticosteroid that will not affect the test results.[29]

If not performed during crisis, then labs to be run should include: random cortisol, serum ACTH, aldosterone, renin, potassium and sodium. A CT of the adrenal glands can be used to check for structural abnormalities of the adrenal glands. An MRI of the pituitary can be used to check for structural abnormalities of the pituitary. However, in order to check the functionality of the Hypothalamic Pituitary Adrenal (HPA) Axis the entire axis must be tested by way of ACTH stimulation test, CRH stimulation test and perhaps an Insulin Tolerance Test (ITT). In order to check for Addison’s Disease, the auto-immune type of primary adrenal insufficiency, labs should be drawn to check 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies[27].

Effects

[edit]| Type | Hypothalamus (tertiary)1 |

Pituitary (secondary) |

Adrenal glands (primary)7 |

| Underlying causes | Abrupt steroid withdrawal, Tumor of the hypothalamus (adenoma), antibodies, environment (i.e. toxins), head injury | Tumor of the pituitary (adenoma), antibodies, environment, head injury, surgical removal6, Sheehan's syndrome | Tumor of the adrenal (adenoma), stress, antibodies, environment, Addison's disease, trauma, surgical removal (resection), miliary tuberculosis of the adrenal |

| CRH | low | high2 | high |

| ACTH | low | low | high |

| DHEA | low | low | high |

| DHEA-S | low | low | high |

| Cortisol | low3 | low3 | low4 |

| Aldosterone | low | normal | low |

| Renin | low | low | high |

| Sodium (Na) | low | low | low |

| Potassium (K) | low | normal | high |

| 1 | Automatically includes diagnosis of secondary (hypopituitarism) |

| 2 | Only if CRH production in the hypothalamus is intact |

| 5 | Most common, does not include all possible causes |

| 6 | Usually because of very large tumor (macroadenoma) |

| 7 | Includes Addison's disease |

Treatment

[edit]The treatment of adrenal insufficiency is glucocorticoid replacement. If an infection is the inciting event of a crisis or cause of primary adrenal failure, then treatment must proceed aggressively. Patients in shock will require intravenous hydration, and often dextrose.

For patients with established adrenal insufficiency, hydrocortisone is the treatment of choice, with 100 mg IV every 8 hours being the standard dose. Hydrocortisone has some mineralocorticoid effect in case the patient has deficient aldosterone.

In an undiagnosed patient, dexamethasone (4 mg initial bolus) should be used, as this does not interfere with cortisol assays.

Mineralocorticoid replacement with fludrocortisone may be required but is not usually necessary in an acute adrenal crisis.

If patients with adrenal insufficiency require surgery, a stress dose of glucocorticoids must be given and continued for 24 hours after the procedure.

- Adrenal crisis

- Intravenous fluids[4]

- Intravenous steroid (Solu-Cortef/injectable hydrocortisone) later hydrocortisone, prednisone or methylpredisolone tablets[4]

- Rest

- Cortisol deficiency (primary and secondary)

- Hydrocortisone (Cortef)

- Prednisone (Deltasone)

- Prednisolone (Delta-Cortef)

- Methylprednisolone (Medrol)

- Dexamethasone (Decadron)

- Mineralocorticoid deficiency (low aldosterone)

(To balance sodium, potassium and increase water retention)[4]

See also

[edit]- Addison's disease – primary adrenocortical insufficiency

- Cushing's syndrome – overproduction of cortisol

- Insulin tolerance test – another test used to identify sub-types of adrenal insufficiency

- Adrenal fatigue (hypoadrenia) – a term used in alternative medicine to describe a believed exhaustion of the adrenal glands

References

[edit]- ^ a b Eileen K. Corrigan (2007). "Adrenal Insufficiency (Secondary Addison's or Addison's Disease)". NIH Publication No. 90-3054.

- ^ Adrenal+Insufficiency at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- ^ Ten S, New M, Maclaren N (2001). "Clinical review 130: Addison's disease 2001". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 86 (7): 2909–22. doi:10.1210/jcem.86.7.7636. PMID 11443143.

- ^ a b c d e f Ashley B. Grossman, MD (2007). "Addison's Disease". Adrenal Gland Disorders.

- ^ Brender E, Lynm C, Glass RM (2005). "JAMA patient page. Adrenal insufficiency". JAMA. 294 (19): 2528. doi:10.1001/jama.294.19.2528. PMID 16287965.

- ^ "Dorlands Medical Dictionary:adrenal insufficiency".

- ^ "Secondary Adrenal Insufficiency: Adrenal Disorders: Merck Manual Professional".

- ^ "hypopituitary". WebMD. 2006.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-06-13. Retrieved 2010-03-31.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Causes of secondary and tertiary adrenal insufficiency in adults". Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ Montgomery ND, Dunphy CH, Mooberry M, Laramore A, Foster MC, Park SI, Fedoriw YD (2013). "Diagnostic complexities of eosinophilia". Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 137 (2): 259–69. doi:10.5858/arpa.2011-0597-RA. PMID 23368869.

- ^ Huecker, Martin R.; Dominique, Elvita (2019), "Adrenal Insufficiency", StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, PMID 28722862, retrieved 2019-12-12

- ^ a b c Table 20-7 in: Mitchell, Richard Sheppard; Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology. Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1. 8th edition.

- ^ Thomas A Wilson, MD (2007). "Adrenal Insufficiency". Adrenal Gland Disorders.

- ^ Bornstein SR, Allolio B, Arlt W, Barthel A, Don-Wauchope A, Hammer GD, et al. (2016). "Diagnosis and Treatment of Primary Adrenal Insufficiency: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline". J Clin Endocrinol Metab (Practice Guideline. Review). 101 (2): 364–89. doi:10.1210/jc.2015-1710. PMC 4880116. PMID 26760044.

- ^ Thomas A Wilson, MD (1999). "Adrenoleukodystrophy".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Link text, additional text.

- ^ a b c d "Clinical review 130: Addison's disease 2001". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 86 (7): 2909–2922. 2001. doi:10.1210/jc.86.7.2909. PMID 11443143.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Kaminstein, David S. William C. Shiel Jr. (ed.). "Steroid Drug Withdrawal". MedicineNet. Retrieved 10 April 2013.

- ^ Dernis, E; Ruyssen-Witrand, A; Mouterde, G; Maillefert, JF; Tebib, J; Cantagrel, A; Claudepierre, P; Fautrel, B; Gaudin, P; Pham, T; Schaeverbeke, T; Wendling, D; Saraux, A; Loët, XL (October 2010). "Use of glucocorticoids in rheumatoid arthritis - practical modalities of glucocorticoid therapy: recommendations for clinical practice based on data from the literature and expert opinion". Joint, Bone, Spine : Revue du Rhumatisme. 77 (5): 451–7. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2009.12.010. PMID 20471886.

- ^ Stitik, Todd P. (2010). Injection Procedures: Osteoarthritis and Related Conditions. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 47. ISBN 9780387765952.

- ^ "21-Hydroxylase, a major autoantigen in idiopathic Addison's disease". The Lancet. 339 (8809): 1559–62. June 1992. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(92)91829-W. PMID 1351548.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ "Clinical manifestations and management of patients with autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type I". Journal of Internal Medicine. 265 (5): 514–29. May 2009. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02090.x. PMID 19382991.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Kennedy, Ron. "Addison's Disease". The Doctors' Medical Library. Archived from the original on 2013-04-12. Retrieved 2015-07-29.

- ^ a b "Adrenal Insufficiency (Addison's Disease)". www.hopkinsmedicine.org. Retrieved 2019-12-12.

- ^ Schrier, R. W. (2006). "Body Water Homeostasis: Clinical Disorders of Urinary Dilution and Concentration". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 17 (7): 1820–32. doi:10.1681/ASN.2006030240. PMID 16738014.

- ^ a b Oelkers, Wolfgang (1996-10-17). "Adrenal Insufficiency". New England Journal of Medicine. 335 (16): 1206–1212. doi:10.1056/NEJM199610173351607. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 8815944.

- ^ "Adrenal Insufficiency Diagnosis". ucsfhealth.org. Retrieved 2019-12-12.

- ^ Addison Disease~workup at eMedicine

- ^ https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/underactive-adrenal-glands--addisons-disease

Further reading

[edit]- Bornstein, SR; Allolio, B; Arlt, W; Barthel, A; Don-Wauchope, A; Hammer, GD; Husebye, ES; Merke, DP; Murad, MH; Stratakis, CA; Torpy, DJ (February 2016). "Diagnosis and Treatment of Primary Adrenal Insufficiency: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 101 (2): 364–89. doi:10.1210/jc.2015-1710. PMC 4880116. PMID 26760044.

External links

[edit]

This template is no longer used; please see Template:Endocrine pathology for a suitable replacement