User:Jprw/Spoilt Rotten: The Toxic Cult of Sentimentality

| Author | Theodore Dalrymple |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Subject | Sentimentality, Cultural studies, Media manipulation |

| Genre | Cultural studies, polemics |

| Publisher | Gibson Square Books Ltd |

Publication date | 29 July 2010 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Pages | 256 |

| ISBN | 1906142610 |

Spoilt Rotten: The Toxic Cult of Sentimentality is a polemical 2010 work by the British writer and retired prison doctor and psychiatrist Theodore Dalrymple. The book attempts to reveal how, in the author's view, sentimentality is becoming culturally entrenched and is having a harmful affect on British society. Dalrymple explores a range of social, educational, political, media and literary issues—including falling standards in education, the Make Poverty History campaign, the death of Princess Diana, the disappearance of Madeleine McCann, and the work and life of poet Sylvia Plath—to illustrate what he views as the danger of abandoning logic in favour of sentimentality, which he describes in the book's introduction as "the progenitor, the godparent, the midwife of brutality".[1] Much of Dalrymple's analysis in the book is underpinned by his experience of working with criminals and the mentally ill.

In July 2010 in two separate articles the author used themes explored in the book to analyse high profile cases in the British media involving Raoul Moat[2] and Jon Venables.[3]

Background

[edit]Synopsis

[edit]| "A sentimentalist is simply one who desires to have the luxury of an emotion without paying for it". Oscar Wilde[4] |

| — Quoted by Dalrymple at the beginning of the book's conclusion |

The book is divided into six chapters. In Chapter One, Sentimentality, Dalrymple observes how sentimentality is increasing as a cultural phenomenon in the United Kingdom, and cites a number of incidents to support this assertion, including a trip to WH Smith in England in which he noticed that a new section of books had appeared, entitled Tragic Life Stories. The section dwarfed the classic novels section, which Dalrymple asserts "surely tells us something about our present Zeitgeist".[5] He then noticed that the section was alongside a section devoted to True Crime, and contends "Here, if anywhere, was an elective affinity. After all, having tragic life stories to weep over depends, is parasitic, upon the brutality of those who make the life stories tragic in the first place".[6] He then recounts the experience of choosing random newspaper articles to study. The first illustrated how the child controlled the parents in a home, and how this was illustrative of how "the parents were transferring the locus of moral, intellectual, and emotional authority from themselves to their daughter";[7] and the second article "depended upon its effect on readers upon another unspoken, widely-accepted but deeply sentimental notion: namely, that in any conflict between a large organisation and an individual, the organisation must be to blame and the individual must have been maltreated".[8] Dalrymple identifies two causes for these incidents: boredom and a compensation culture. He then analyses the issue of falling education standards in the UK, and why, despite expenditure on education being four times more per head than in 1950:

- Standards of literacy have not risen in the country and "may have fallen";[9]

- Employers now complain of graduates "not being able to compose a simple letter";[9]

- A lecturer at Imperial College London recently remarked that foreign students often wrote better English than British ones;[9]

- Spelling errors are now far more frequently made by doctors in medical notes than previously;[9]

- A friend of the author at Oxford is instructed not to mark students down for their poor grammar, spelling and composition.[10]

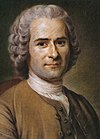

Dalrymple identifies that the above malaise is linked to "powerful intellectual currents" that "feed into the great Sargasso Sea of modern sentimentality about children", and asserts that the ideas of eighteenth philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau[10] and modern psychologist Steven Pinker[11] have been particularly influential in this respect.

Dalrymple then examines another article[12] in which a prominent member of the British clergy urges reform of the British prison system. Dalrymple writes of the article: "There is little doubt that the tendency of the article, and probably its intention, was to arouse a certain emotion—again—whose effect, if not its intention, was to convince the person experiencing it that he was a person of superior sensibility and compassion",[13] and that the kind of emotionality seen in the article "often attaches to the question of crime and punishment in contemporary Britain".[13] Dalrymple also draws attention to a modern tendency in which it is often implied that a criminal under the influence of drugs or alcohol is not morally responsible for his crimes, and quotes Aristotle that "a man who committed an offence while intoxicated was double guilty: first of the offence itself, and second of having intoxicated himself";[14] Dalrymple maintains that it is "the sheerest sentimentality to see drug addicts as the victims of an illness".[15] The author concludes the chapter by stating that "sentimentality is now a mass phenomenon almost beyond criticism or even comment" [14] and that the phenomenon has also extended to informalising the inscriptions seen on tombstones, "as if death itself can, by the employment of informal and sentimental, or even aggressive language, be reduced to a mere incident of everyday life".[16]

In Chapter Two, What is Sentimentality? Dalrymple advances that the kind of sentimentality that he wishes to draw attention to is "an excess of emotion that is false, mawkish, and over-valued by comparison with reason"[17] and which is performed "in full public view".[18] He then spends much of the chapter taking issue with assertions made by the philosopher Robert C. Solomon that sentimentality does not:

- involve or provoke excessive expression of emotion;[19]

- manipulate emotions;[19]

- cause false emotions to be shown;[19]

- involve the expression of cheap, easy and superficial emotions;[19]

- constitute self-indulgence;[19]

- distort perception and interfere with rational thought.[19]

Dalrymple contends that "Sentimentality is the expression of emotion without judgment. Perhaps it is worse than that: it is the expression of emotion without an acknowledgement that judgment should enter into how we should react to what we see and hear. It is the manifestation of a desire for the abrogation of an existential condition of human life, namely the need to always and never unendingly to exercise judgement. Sentimentality is therefore childish and therefore reductive of our humanity".[20]

In Chapter Three, The Family Impact Statement, Dalrymple criticises the introduction by Harriet Harman into British court proceedings of the The Family Impact Statement, designed ostensibly to allow the families of a victim of a crime to play some role in court proceedings. Dalrymple however points out that such statements "are not permitted to influence the outcome of a case. They are made only after a jury has made its verdict"[21] and that in practice this is not made clear to victims' families. As a result, kitsch displays of emotion are encouraged in court, of no practical benefit. Moreover, Dalrymple contends that such statements are "an elaborate ruse to mislead the families of murdered people, and the public, into thinking that the criminal justice system and the government is sensitive to to their concerns about the high levels of crime in society".[22]

Dalrymple begins Chapter Four, The Demand for Public Emotion, by analysing the media attention and reaction to the disappearance of Madeleine McCann, and specifically how certain elements in the media interpreted the lack of emotion displayed by the girl’s parents as evidence of guilt. Dalrymple writes that the "demand that emotion should be shown in public, or be assumed not to exist and therefore indicate a guilty mind, is now not an uncommon one" [23] and draws a comparison between the McCanns and two Australian cases involving Joanne Lees and Linda Chamberlain. He then analyses the outcry from the public and the media to the lack of emotion shown by the Queen in the wake of Princess Diana's death, and contends that "the tabloid newspapers carried out what can only be called a campaign of bullying against the sovereign"[24] and that the crowds that gathered outside Buckingham Palace were "without the self-knowledge that they were bullying rather than expressing any genuine grief".[25] Dalrymple contends that the "demand that the Queen show the crowd that she cared, as the crowd claimed itself to care…subverts the whole notion of honesty and proportion of expression".[26] He concludes the chapter by asserting that the "sentimentality, both spontaneous and generated by the exaggerated attention of the media, that was necessary to turn the death of the princess into an event of such magnitude thus served a political purpose, one that was inherently dishonest in a way that parallels the dishonesty that lies behind much sentimentality itself".[27]

| "The elevation of the status of the suffering victim occurred in the west not when real and terrible mass victimisation was of very recent memory, but when Western Europe and America seemed to have recovered from the worst excesses of such victimisation, and indeed were prospering. Sylvia Plath had not been a victim of anything, or at least of anything political, when she used imagery from the holocaust to describe her own case; within a few years of the publication of her poems, the well-heeled and fashionably dressed students of Paris were chanting such slogans as 'We're all German Jews'. The students drew cartoons of General de Gaulle with his physiognomy as a mask behind which was the real face of Hitler, with the implication that the Fifth Republic was some kind of covert Nazi dictatorship of which the students were oppressed victims. Far from being victims, they were the very elite of the country, destined before long to reach positions of social, economic and political power. But they were pioneers in what became a cultural trend: the desire and ability of the privileged to see themselves as victims, and therefore endowed with incontrovertible moral authority". [28] |

| — Extract from Chapter 5, "The Cult of the Victim" |

In Chapter Five, The Cult of the Victim, Dalrymple analyses the poet Sylvia Plath, who he describes as the "patron saint of self-dramatization".[29] He interprets Margaret Drabble's description of Plath as being a "willing casualty" and "supremely vulnerable"[30] as "virtues of a high order".[27] Dalrymple then analyses Plath's relationship with her father, how she blamed him for her own suffering, and how, because of his German background, she identifies him in one of her poems – "Daddy" – with Nazism, and makes allusions to the holocaust. Dalrymple writes that "in order to attract the attention to the reader to her suffering, to her existenial angst, Plath felt it right to allude to one of the worst and most deliberate inflictions of mass-suffering in the whole of human history, merely on the basis that her father, who died when she was young, was German"[31] and that "her connection with the holocaust was tenuous to say the least...in fact, the metaphorical use of the holocaust measures not the scale of her suffering, but of her self-pity".[31] Dalrymple alleges that prior to the emergence of Plath, self-pity "was regarded as a vice, even a disgusting one, that precluded sympathy"[32] and he quotes as an example lines from John Buchan's book Sick Heart River:

He had made a niche for himself in the world, but it had been a chilly niche. With a start he awoke to the fact that he was very near the edge of self-pity, a thing forbidden.[32]

Dalrymple writes that the book's hero does not "allow himself the luxury of self-pity even within the confines of his own skull, for he knew that internal indulgence would lead before long to external expression".[32]

Dalrymple asserts that "the appropriation of the suffering of others to boost the scale and significance of one's own suffering is now a commonplace. It is an international trend",[32] and in this connection he then analyses the figures Binjamin Wilkomirski, Laura Grabowski, Misha Defonseca, Rigoberta Menchú, Margaret Seltzer, and James Frey, all of whom according to Dalrymple "make bogus claims to victim status"[33] and whose stories reveal perfectly "the dialectic between sentimentality and brutality".[34] Dalrymple ends the chapter by analysing the emergence of the phenomenon of victimhood in the criminal justice system, and concludes "For the sentimenatlist, of course, there is no such thing as a criminal, only an environment that has let him down".[35]

Dalrymple begins the final chapter, Make Poverty History!, by trying to establish which type of poverty the campaigners behind the Make Poverty History campaign are trying to eradicate, and surmises that it must be "the kind of poverty that exists so long as incomes are not equal, that is to say among people whose income is less than sixty percent of that of the median income, a definition that is often used and means that, in a society of billionaires, a multi-millionaire could be considered poor".[36] Dalrymple then contends that chronic poverty has decreased considerably in the last twenty five years, but principally in China and India, and that as a result "Africa is an exception and therefore is the current focus of sentimentality about poverty".[37] In this context he then explores the wish frequently expressed by Gordon Brown during his time as prime minister to "ensure that every child on the continent [African] should at least have a primary education".[38] Dalrymple dismisses this as a pure exercise in sentimental public posturing, and question whether there is in fact a link between improving educational standards and increasing economic growth on the continent, citing as examples the experience of Tanzania under Julius Nyerere,[39] and Equatorial Guinea under Macias Nguema.[40] Dalrymple adds "the fate of Sierra Leone, with a long history of historical effort and achievement, does not fortify one's faith in the role of economic advancement",[41] and argues that what Africa needs as an immediate priority is access to markets.[39] Dalrymple also contends that the majority of aid sent to Africa is captured by its leaders[42] or used to fund civil wars.[43] He concludes that the position adopted by Gordon Brown smacks of "Singerian moral universalism",[43] which he labels "preposterous—psychologically, theoretically, and practically".[43]

In the books conclusion Dalrymple contends that "in field after field, sentimentality has triumphed",[44] and this has led to:

- the lives of millions of children being blighted by overindulgence and neglect;

- the destruction of educational standards;

- the cause of untold misery because of the theory of human relations it has espoused;

- brutality wherever the policies suggested by sentimentality have been advocated.

Dalrymple ends the book by writing that "The cult of feeling destroys the ability to think, or even the awareness that it is necessary to think. Pascal was absolutely right when he said

Travaillons donc à bien penser. Voilà le principe de la morale.[44]

Release details

[edit]The book was originally published in the UK on 29 July 2010 by Gibson Square Books Ltd. The book had at least one alternative sub-title before The Toxic Cult of Sentimentality was finally chosen upon; the US edition of the book has the sub-title How Britain is Ruined by Its Children. The book's front cover features a wrongly attributed comment "a taboo-shattering, sacred cow-slaughtering, myth-destroying little gem of a book" by Dominic Lawson; Lawson had in fact written the comment in 2007 in a review[45] of another Dalrymple US-published book, Romancing Opiates: Pharmacological Lies and the Addiction Bureaucracy.

Critical reception

[edit]The book was described by Toby Young in The Daily Telegraph as being an "excellent new book attacking the cult of sentimentality" and that Dalrymple also "makes a convincing case that standards in British education have plummeted in the last few decades".[46]

Bibliography

[edit]- Dalrymple, Theodore (2010). Spoilt Rotten: The Toxic Cult of Sentimentality. Gibson Square Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1906142612.

See also

[edit]- Compensation culture

- Media manipulation

- Sentimentalism (literature)

- Live Aid (criticisms and controversies)

References

[edit]- ^ Dalrymple 2010, p. 50

- ^ Theodore Dalrymple (17 July 2010). "Sentimentality is poisoning our society". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 31 July 2010.

- ^ Theodore Dalrymple (25 July 2010). "JON VENABLES: THE LITTLE LORD FAUNTLEROY OF CRIME". The Daily Express. Retrieved 2 August 2010.

- ^ Dalrymple 2010, p. 229

- ^ Dalrymple 2010, p. 53

- ^ Dalrymple 2010, p. 54

- ^ Dalrymple 2010, p. 56

- ^ Dalrymple 2010, p. 60

- ^ a b c d Dalrymple 2010, p. 65

- ^ a b Dalrymple 2010, p. 66

- ^ Dalrymple 2010, p. 67

- ^ Rowan Walker (18 November 2007). "Cardinal urges prison reform". The Observer. Retrieved 31 July 2010.

- ^ a b Dalrymple 2010, p. 69

- ^ a b Dalrymple 2010, p. 75

- ^ Dalrymple 2010, p. 79

- ^ Dalrymple 2010, p. 81

- ^ Dalrymple 2010, p. 82

- ^ Dalrymple 2010, p. 83

- ^ a b c d e f Dalrymple 2010, p. 85

- ^ Dalrymple 2010, p. 100

- ^ Dalrymple 2010, p. 115

- ^ Dalrymple 2010, p. 123

- ^ Dalrymple 2010, p. 138

- ^ Dalrymple 2010, p. 144

- ^ Dalrymple 2010, p. 146

- ^ Dalrymple 2010, p. 149

- ^ a b Dalrymple 2010, p. 154

- ^ Dalrymple 2010, p. 183

- ^ Dalrymple 2010, p. 157

- ^ Margaret Drabble (8 March 2008). "Great poets". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ^ a b Dalrymple 2010, p. 160

- ^ a b c d Dalrymple 2010, p. 161

- ^ Dalrymple 2010, p. 166

- ^ Dalrymple 2010, p. 167

- ^ Dalrymple 2010, p. 204

- ^ Dalrymple 2010, p. 206

- ^ Dalrymple 2010, p. 207

- ^ Dalrymple 2010, p. 208

- ^ a b Dalrymple 2010, p. 210

- ^ Dalrymple 2010, p. 213

- ^ Dalrymple 2010, p. 214

- ^ Dalrymple 2010, p. 225

- ^ a b c Dalrymple 2010, p. 226

- ^ a b Dalrymple 2010, p. 231

- ^ Dominic Lawson (6 February 2007). "Dominic Lawson: Addiction is a moral, not a medical, problem". The Independent. Retrieved 31 July 2010.

- ^ Toby Young (13 July 2010). "Universities are now handing out First Class degrees like confetti". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 31 July 2010.

External links

[edit]- The Skeptical Doctor (detailed biography, links to current writings, book reviews, speeches and interviews)

Category:2010 books Category:Psychological anthropology Category:Psychology books Category:Social conservatism Category:Political correctness Category:Polemics Category:Media manipulation techniques Category:Media influence Category:Cultural history of the United Kingdom