User:Drdpw/sandbox1

| This page in a nutshell: This page is a sandbox page of Drdpw and is not an encyclopedia article. It serves as my testing spot and page development space for proposed Wikipedia articles. I also have two other sandboxes: User:Drdpw/sandbox and User:Drdpw/sandbox2. |

◆

◆

◆

First presidency of Grover Cleveland

Portrait, 1892 | |

| Presidencies of Grover Cleveland | |

| Party | Democratic |

|---|---|

| Election | |

| Seat | White House |

First term March 4, 1885 – March 4, 1889 | |

| Cabinet | See list |

Second term March 4, 1893 – March 4, 1897 | |

| Cabinet | See list |

|

| |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Personal

28th Governor of New York

22nd & 24th President of the United States

First presidency

Inter-presidency

Second presidency

Presidential campaigns

Retirement

|

||

Grover Cleveland was president of the United States first from March 4, 1885, to March 4, 1889, and then from March 4, 1893, to March 4, 1897. The first Democrat elected after the Civil War, Cleveland was the first U.S. president to leave office after one term and later be elected for a second term,[a] and the only one to date to have served two full non-consecutive terms. His presidencies were the nation's 22nd and 24th.[b] Cleveland defeated James G. Blaine of Maine in 1884, lost to Benjamin Harrison of Indiana in 1888, and then defeated President Harrison in 1892. He was succeeded by Republican William McKinley, who won in 1896.

Cleveland won the 1884 election with the support of a reform-minded group of Republicans known as Mugwumps, and he expanded the number of government positions that were protected by the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act. He also vetoed several bills designed to provide pensions and other benefits to various regions and individuals. In response to anti-competitive practices by railroads, Cleveland signed the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887, which established the first independent federal agency. During his first term, he unsuccessfully sought the repeal of the Bland–Allison Act and a lowering of the tariff. The Samoan crisis was the major foreign policy event of Cleveland's first term, and that crisis ended with a tripartite protectorate in the Samoan Islands.

As his second term began, disaster hit the nation when the Panic of 1893 produced a severe national depression. Cleveland presided over the repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, striking a blow against the Free Silver movement, and also lowered tariff rates by allowing the Wilson–Gorman Tariff Act to become law. He also ordered federal soldiers to crush the Pullman Strike. In foreign policy, Cleveland resisted the annexation of Hawaii and an American intervention in Cuba. He also sought to uphold the Monroe Doctrine and forced Great Britain to agree to arbitrate a border dispute with Venezuela. In the midterm elections of 1894, Cleveland's Democratic Party suffered a massive defeat that opened the way for the agrarian and silverite seizure of the Democratic Party.

The 1896 Democratic National Convention repudiated Cleveland and nominated silverite William Jennings Bryan, but Bryan was defeated by Republican William McKinley in the subsequent election. Cleveland left office extremely unpopular, but his reputation was eventually rehabilitated in the 1930s by scholars led by Allan Nevins. More recent historians and biographers have taken a more ambivalent view of Cleveland, but many note Cleveland's role in re-asserting the power of the presidency. In rankings of American presidents by historians and political scientists, Cleveland is generally ranked as an average or above-average president.

Election of 1884

[edit]Cleveland had risen to prominence as an advocate of civil service reform, and he was widely viewed as a presidential contender after his victory in the 1882 New York gubernatorial election.[1] Samuel J. Tilden, the party's nominee in 1876, was the initial front-runner, but he declined to run due to poor health.[2] Cleveland, Thomas F. Bayard of Delaware, Allen G. Thurman of Ohio, Samuel Freeman Miller of Iowa, and Benjamin Butler of Massachusetts each had considerable followings entering the 1884 Democratic National Convention.[2] Each of the other candidates had hindrances to his nomination: Bayard had spoken in favor of secession in 1861, making him unacceptable to Northerners; Butler, conversely, was reviled throughout the South for his actions during the Civil War; Thurman was generally well liked, but was growing old and infirm, and his views on the silver question were uncertain.[3]

Cleveland, too, had detractors—the Tammany Hall political machine opposed him—but the nature of his enemies made him still more friends.[4] He also benefited from the backing of state party leader Daniel Manning, who positioned Cleveland as the natural heir to Tilden and emphasized the importance of New York's electoral votes in any Democratic presidential victory.[5] Cleveland led on the convention's first ballot and clinched the nomination on the second ballot.[6] Thomas A. Hendricks of Indiana was selected as his running mate.[6] The 1884 Republican National Convention nominated former Speaker of the House James G. Blaine of Maine for president; Blaine's nomination alienated many Republicans who viewed Blaine as ambitious and immoral.[7]

Blaine campaigned on implementing a protective tariff, increasing international trade, and investing in infrastructure projects, while the Democratic campaign focused on Blaine's ethics.[8] In general, Cleveland abided by the precedent of minimizing presidential campaign travel and speechmaking; Blaine became one of the first to break with that tradition.[9] Corruption in politics became the central issue in 1884, and Blaine had over the span of his career been involved in several questionable deals.[10] Cleveland's reputation as an opponent of corruption proved the Democrats' strongest asset.[11] Reform-minded Republicans called "Mugwumps", including men such as Carl Schurz and Henry Ward Beecher, denounced Blaine as corrupt and flocked to Cleveland.[12] At the same time the Democrats gained support from the Mugwumps, they lost some blue-collar workers to the Greenback-Labor party, led by Benjamin Butler.[13]

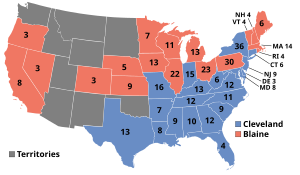

As expected, Cleveland carried the Solid South, while Blaine carried most of New England and the Midwest. The electoral votes of closely contested New York, New Jersey, Indiana, and Connecticut determined the election.[14] After the votes were counted, Cleveland narrowly won all four of the swing states; he won his home state of New York by a margin of 0.1%, which amounted to just 1200 votes.[15] Cleveland won the nationwide popular vote by one-quarter of a percent, while he won the electoral vote by a majority of 219–182.[15] Cleveland's victory made him the first successful Democratic presidential nominee since the start of the Civil War. Despite Cleveland's successful candidacy, Republicans retained control of the Senate.

First presidency (1885–1889)

[edit]

Cleveland was sworn into office as the 22nd president of the United States on March 4, 1885. That same day, Hendricks was sworn in as vice president. Hendricks died 266 days into this term, and the office remained vacant since there was no constitutional provision at the time for filling an intra-term vice-presidential vacancy.

Administration

[edit]Appointments

[edit]| The First Cleveland cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Grover Cleveland | 1885–1889 |

| Vice President | Thomas A. Hendricks | 1885 |

| none | 1885–1889 | |

| Secretary of State | Thomas F. Bayard | 1885–1889 |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Daniel Manning | 1885–1887 |

| Charles S. Fairchild | 1887–1889 | |

| Secretary of War | William Crowninshield Endicott | 1885–1889 |

| Attorney General | Augustus H. Garland | 1885–1889 |

| Postmaster General | William F. Vilas | 1885–1888 |

| Donald M. Dickinson | 1888–1889 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | William Collins Whitney | 1885–1889 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar | 1885–1888 |

| William F. Vilas | 1888–1889 | |

| Secretary of Agriculture | Norman Jay Colman | 1889 |

There was much speculation during the presidential transition period about who would be serving in Cleveland's cabinet. It was generally assumed that Thomas F. Bayard would be offered the position of secretary of state.[16] By February 27, 1885, Cleveland had been reported to have settled on all the officeholders for his Cabinet.[17] However, Daniel S. Lamont, Cleveland's private secretary, immediately denied reports that Cleveland had settled upon his Cabinet choices, and that he had announced his selections to others.[18]

Front row, left to right: Thomas F. Bayard, Cleveland, Daniel Manning, Lucius Q. C. Lamar

Back row, left to right: William F. Vilas, William C. Whitney, William C. Endicott, Augustus H. Garland

Cleveland faced the challenge of putting together the first Democratic cabinet since the 1850s, and none of the individuals that he appointed to his cabinet had served in the cabinet of another administration. Senator Bayard, Cleveland's strongest rival for the 1884 nomination, accepted the position of Secretary of State. Daniel Manning, a key New York adviser for Cleveland as well as a close ally of Samuel Tilden, became the Secretary of the Treasury. Another New Yorker, the prominent financier William C. Whitney, was appointed Secretary of the Navy. For the position of Secretary of War, Cleveland appointed William C. Endicott, a prominent Massachusetts judge with ties to the Mugwumps. Cleveland chose two Southerners for his cabinet: Lucius Q. C. Lamar of Mississippi as Secretary of the Interior, and Augustus H. Garland of Arkansas as Attorney General. Postmaster General William F. Vilas of Wisconsin was the lone Westerner in the cabinet. Daniel S. Lamont served as Cleveland's private secretary, becoming one of the most important individuals in the administration.[19]

Marriage and children

[edit]

Cleveland entered the White House as a bachelor, and his sister Rose Cleveland acted as hostess for the first two years of his administration.[20] On June 2, 1886, Cleveland married Frances Folsom in the Blue Room at the White House.[21] Though Cleveland had supervised Frances's upbringing after her father's death, the public took no exception to the match.[22] At 21 years, Frances Folsom Cleveland was the youngest First Lady in history, and the public soon warmed to her beauty and warm personality.[23]

Reforms and civil service

[edit]Presidential appointments until now were typically filled under the spoils system. However Cleveland announced that he would not fire any Republican who was doing his job well, and would not appoint anyone solely on the basis of party service.[24] Later in his term, as his fellow Democrats chafed at being excluded from the patronage, Cleveland began to replace more of the partisan Republican officeholders with Democrats;[25] this was especially the case with policy-making positions.[26] While some of his decisions were influenced by party concerns, more of Cleveland's appointments were decided by merit alone than was the case in his predecessors' administrations.[27] During his first term, Cleveland also expanded the number of federal positions subject to the merit system (under the terms of the recently passed Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act) from 16,000 to 27,000. Due to Cleveland's and Harrison's efforts, between 1885 and 1897, the percentage of federal employees protected by the Pendleton Act rose from twelve percent to forty percent. Nonetheless, many Mugwumps were disappointed by Cleveland's unwillingness to promote a truly nonpartisan civil service.[28]

Cleveland was the first Democratic president subject to the Tenure of Office Act, which originated in 1867; the act purported to require the Senate to approve the dismissal of any presidential appointee who was originally subject to its advice and consent.[29] Cleveland resisted the Senate's attempts to enforce the act, and invoked executive privilege in refusing to hand over documents related to appointments. Despite criticism from reformers like Carl Schurz, Cleveland's stance proved popular with the public. Republican Senator George Frisbie Hoar proposed a bill to repeal the Tenure of Office Act, and Cleveland signed the repeal into law in March 1887.[30][c]

In 1889, Cleveland signed into law a bill that elevated the Department of Agriculture to the cabinet level, and Norman Jay Coleman became the first United States Secretary of Agriculture.[31] Cleveland angered railroad investors by ordering an investigation of Western lands they held by government grant.[32] Secretary of the Interior Lamar charged that the rights of way for this land must be returned to the public because the railroads failed to extend their lines according to agreements.[32] The lands were forfeited, resulting in the return of approximately 81,000,000 acres (330,000 km2).[32]

Interstate Commerce Act

[edit]During the 1880s, public support for the regulation of railroads grew because of anger over anti-competitive railroad practices such as "discrimination," in which the railroads charged different rates to different clients.[33] Though often critical of the business practices of railroad magnates like Jay Gould, Cleveland was generally reluctant to involve the federal government in regulatory matters. Despite this reluctance, after the Supreme Court's holding in the 1886 case of Wabash, St. Louis & Pacific Railway Co. v. Illinois severely limited the power of states to regulate interstate commerce, Cleveland assented to legislation providing for federal oversight of railroads. In 1887, he signed the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887, which created the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), a five-member commission tasked with investigating railroad practices. The ICC was charged with helping to ensure that the railroads charged fair rates, but the power to determine whether rates were fair was assigned to the courts.[34] In addition to creating the ICC, the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887 required railroads to publicly post rates and made the practice of railroad pooling illegal.[33] The act was the first federal law to regulate private industry in the United States,[35] and the ICC was the first independent agency of the federal government.[36] The Interstate Commerce Act had only a modest effect on railroad practices, as talented railroad lawyers and a conservative judiciary limited the impact of the various provisions of the law.[37]

Vetoes

[edit]Cleveland used the veto far more often than any president up to that time.[38] He vetoed hundreds of private pension bills for Civil War veterans, believing that if their pensions requests had already been rejected by the Pension Bureau, Congress should not attempt to override that decision.[39] When Congress, pressured by the Grand Army of the Republic, passed a bill granting pensions for disabilities not caused by military service, Cleveland also vetoed that.[40] In 1887, Cleveland issued his most well-known veto, of the Texas Seed Bill.[41] A severe drought had devastated many in Texas, with some numbers suggesting that 85% of cattle died in the western part of the state. Many farmers themselves were on the brink of starvation as a result of the crisis.[42] Congress, in response, appropriated $10,000 to purchase seed grain for farmers there.[41] Cleveland vetoed the expenditure. In his veto message, he espoused a theory of limited government:

I can find no warrant for such an appropriation in the Constitution, and I do not believe that the power and duty of the general government ought to be extended to the relief of individual suffering which is in no manner properly related to the public service or benefit. A prevalent tendency to disregard the limited mission of this power and duty should, I think, be steadfastly resisted, to the end that the lesson should be constantly enforced that, though the people support the government, the government should not support the people. The friendliness and charity of our countrymen can always be relied upon to relieve their fellow-citizens in misfortune. This has been repeatedly and quite lately demonstrated. Federal aid in such cases encourages the expectation of paternal care on the part of the government and weakens the sturdiness of our national character, while it prevents the indulgence among our people of that kindly sentiment and conduct which strengthens the bonds of a common brotherhood.[43]

Monetary policy

[edit]One of the most volatile issues of the 1880s was whether the currency should be backed by gold and silver, or by gold alone.[44] The issue cut across party lines, with Western Republicans and Southern Democrats joining in the call for the free coinage of silver, and both parties' representatives in the Northeast favoring the gold standard.[45] Because silver was worth less than its legal equivalent in gold, taxpayers paid their government bills in silver, while international creditors demanded payment in gold, resulting in a depletion of the nation's gold supply.[45] Bimetallism tended to result in inflation, which in turn made it easier for debtors to pay off their loans and increased agricultural prices. It was thus popular in many agrarian states.[46]

Cleveland saw monetary policy as both an economic and moral issue; he thought that adherence to the gold standard would ensure a stable currency, and also felt that those who had extended loans should not be penalized by rising inflation.[46] Cleveland and Treasury Secretary Manning tried to reduce the amount of silver that the government was required to coin under the Bland–Allison Act of 1878.[47] Cleveland also unsuccessfully appealed to Congress to repeal this law before he was inaugurated.[48] In reply, one of the foremost silverites, Richard P. Bland, introduced a bill in 1886 that would require the government to coin unlimited amounts of silver, inflating the then-deflating currency.[49] While Bland's bill was defeated, so was a bill the administration favored that would repeal any silver coinage requirement.[49] The result was a retention of the status quo, and a postponement of the resolution of the Free Silver issue.[50]

Tariffs

[edit]| When we consider that the theory of our institutions guarantees to every citizen the full enjoyment of all the fruits of his industry and enterprise, with only such deduction as may be his share toward the careful and economical maintenance of the Government which protects him, it is plain that the exaction of more than this is indefensible extortion and a culpable betrayal of American fairness and justice ... The public Treasury, which should only exist as a conduit conveying the people's tribute to its legitimate objects of expenditure, becomes a hoarding place for money needlessly withdrawn from trade and the people's use, thus crippling our national energies, suspending our country's development, preventing investment in productive enterprise, threatening financial disturbance, and inviting schemes of public plunder. |

| -- Cleveland's third annual message to Congress, December 6, 1887.[51] |

American tariff rates had increased dramatically during the Civil War, and by the 1880s the tariff brought in so much revenue that the government was running a surplus.[52] Cleveland had not campaigned on the tariff in the 1884 election, but his cabinet, like most Democrats, were sympathetic to calls for lower tariffs.[53] Cleveland's opposition to protective tariffs was rooted in his belief that they unfairly benefited certain industries, and unfairly taxed consumers, by raising prices.[54] Republicans, by contrast, generally favored a high tariff to protect American industries from foreign competitors.[55] Cleveland recommended a reduction of the tariff as part of his first two annual messages to Congress, and he devoted the entirety of his 1887 annual message to tariff reduction.[56] Cleveland warned that the budget surpluses caused by the high tariffs would lead to a financial crisis.[57]

Despite Cleveland's advocacy, no major tariff bill passed during Cleveland's first presidency. In 1886, a bill to reduce the tariff was narrowly defeated in the House.[58] Republicans, as well as protectionist Northern Democrats like Samuel J. Randall, believed that American industries would fail absent high tariffs, and continued to fight efforts to lower tariffs.[59] Roger Q. Mills, chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, proposed a bill to reduce the tariff from about 47% to about 40%.[60] After significant exertions by Cleveland and his allies, the bill passed the House.[60] Senate Republicans countered by introducing the Blair Education Bill, which would have granted federal educational aid to states based on illiteracy rates. The bill passed the Senate with the support of many Southern Democrats, whose constituents benefited disproportionately from the bill. The Senate refused to pass the Mills Tariff, while the House refused to pass the Blair Education Bill.[61] Debate over the tariff persisted into the 1888 presidential election.[62]

Foreign policy, 1885–1889

[edit]Cleveland was a committed non-interventionist who had campaigned in opposition to expansion and imperialism. He refused to support the Frelinghuysen-Zavala Treaty, negotiated by the lame duck Arthur Administration, which would have allowed the United States to build a canal in Nicaragua connecting the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean.[63][64] He did, however, see the Monroe Doctrine as an important plank of foreign policy, and he sought to protect American hegemony in the Western Hemisphere.[65] Secretary of State Bayard negotiated with Joseph Chamberlain of Great Britain over fishing rights in the waters off Canada, and struck a conciliatory note, despite the opposition of New England's Republican senators.[66][67] Cleveland also withdrew from Senate consideration the Berlin Conference treaty, which guaranteed an open door for U.S. interests in the Congo.[68]

Cleveland's presidency saw the start of the Samoan crisis between the U.S., Germany, and Great Britain.[69] Each of those nations had signed a treaty with Samoa under which they were allowed to engage in trade and maintain a naval base, but Cleveland feared that the Germans sought to annex Samoa after the Germans attempted to remove Malietoa Laupepa as the monarch of Samoa in favor of Tuiātua Tupua Tamasese Titimaea. The U.S. encouraged another claimant to the throne, Mata'afa Iosefo, to rebel against Malietoa, and in doing so Mata'afa's forces killed a contingent of German naval guards. German Chancellor Otto Von Bismarck threatened a retaliatory war, but Germany backed down in the face of American and British resistance. In a subsequent conference that took place shortly after Cleveland left office, the United States, Germany, and Britain agreed to make Samoa a joint protectorate.[70][71]

Military policy, 1885–1889

[edit]Cleveland's military policy emphasized self-defense and modernization. In 1885 Cleveland established the Board of Fortifications under Secretary of War Endicott to recommend a new coastal fortification system for the United States.[72][73] No improvements to U.S. coastal defenses had been made since the late 1870s.[74][75] The board's 1886 report recommended a massive $127 million construction program at 29 harbors and river estuaries, to include new breech-loading rifled guns, mortars, and naval minefields. Most of the board's recommendations were implemented, and by 1910, 27 locations were defended by over 70 forts.[76][77]

Secretary of the Navy Whitney promoted the modernization of the Navy, although no ships were constructed that could match the best European warships. Construction of four steel-hulled warships that had begun under the Arthur administration was delayed due to a corruption investigation and subsequent bankruptcy of their building yard, but these ships were completed in a timely manner once the investigation was over.[78] Sixteen additional steel-hulled warships were ordered by the end of 1888; these ships later proved vital in the Spanish–American War of 1898, and many served in World War I. These ships included the "second-class battleships" Maine and Texas, which were designed to match modern armored ships recently acquired by South American countries from Europe. Eleven protected cruisers (including Olympia), one armored cruiser, and one monitor were also ordered, along with the experimental cruiser Vesuvius.[79]

Civil rights and immigration

[edit]Cleveland, like a growing number of Northerners (and nearly all white Southerners), believed that Reconstruction had been a failed experiment. He was unwilling to use federal power to enforce the Fifteenth Amendment, which guaranteed voting rights to African-Americans.[80] Though Cleveland appointed no black Americans to patronage jobs, he allowed Frederick Douglass to continue in his post as recorder of deeds in Washington, D.C. and appointed another black man to replace Douglass upon his resignation.[80]

Cleveland generally did not embrace nativism or immigration restrictions, but he believed that the purpose of immigration was to attract immigrants who would assimilate into American society. Early in his tenure, Cleveland condemned "outrages" against Chinese immigrants, but he eventually came to believe that the deep animosity towards Chinese immigrants in the United States would prevent their assimilation. Secretary of State Bayard negotiated an extension to the Chinese Exclusion Act, and Cleveland lobbied the Congress to pass the Scott Act, written by Congressman William Lawrence Scott, which prevented the return of Chinese immigrants who left the United States. The Scott Act easily passed both houses of Congress, and Cleveland signed it into law in October 1888.[81]

Indian policy

[edit]Approximately 250,000 Native Americans lived in the United States when Cleveland took office, a dramatic decline from previous decades.[82] Cleveland viewed Native Americans as wards of the state, saying in his first inaugural address that "[t]his guardianship involves, on our part, efforts for the improvement of their condition and enforcement of their rights."[83] Cleveland encouraged the idea of cultural assimilation, pushing for the passage of the Dawes Act, which provided for distribution of Indian lands to individual members of tribes, rather than having them continued to be held in trust for the tribes by the federal government.[83] While a conference of Native leaders endorsed the act, in practice the majority of Native Americans disapproved of it.[84] Cleveland believed the Dawes Act would lift Native Americans out of poverty and encourage their assimilation into white society, but it ultimately weakened the tribal governments because it allowed individual Indians to sell tribal land and keep the money for themselves.[83] Between 1881 and 1900, the total land held by Native Americans fell from 155 million acres to 77 million acres.[85]

In the month before Cleveland's 1885 inauguration, President Arthur opened four million acres of Winnebago and Crow Creek Indian lands in the Dakota Territory to white settlement by executive order.[86] Tens of thousands of settlers gathered at the border of these lands and prepared to take possession of them.[86] Cleveland believed Arthur's order to be in violation of treaties with the tribes, and rescinded it on April 17 of that year, ordering the settlers out of the territory.[86] Cleveland sent in eighteen companies of Army troops to enforce the treaties and ordered General Philip Sheridan, at the time Commanding General of the U.S. Army, to investigate the matter.[86]

Judicial appointments

[edit]

During his first term, Cleveland successfully nominated two justices to the Supreme Court of the United States. After Associate Justice William Burnham Woods died, Cleveland nominated Interior Secretary Lucius Q.C. Lamar to the Supreme Court in late 1887. While Lamar had been well-liked as a Senator, his service under the Confederacy two decades earlier caused many Republicans to vote against him. Lamar's nomination was confirmed by the narrow margin of 32 to 28.[87]

Chief Justice Morrison Waite died in March 1888, and Cleveland nominated Melville Fuller to fill his seat. Though Fuller had previously declined Cleveland's nomination to the Civil Service Commission, he accepted the nomination to the Supreme Court. The Senate Judiciary Committee spent several months examining the little-known nominee, before the Senate confirmed the nomination 41 to 20.[88][89] Fuller served as Chief Justice until 1910, presiding over a court that inaugurated the Lochner era.[90]

Election of 1888

[edit]

With little opposition, Cleveland won re-nomination at the 1888 Democratic National Convention, making him the first Democratic president to win re-nomination since Martin Van Buren in 1840. Vice President Hendricks having died in 1885, the Democrats chose Allen G. Thurman of Ohio to be Cleveland's new running mate.[91] Former Senator Benjamin Harrison of Indiana defeated John Sherman and several other candidates to win the presidential nomination of the 1888 Republican National Convention.[92] The Republicans campaigned heavily on the tariff issue, turning out protectionist voters in the important industrial states of the North.[93] Democrats in the crucial swing state of New York were divided over the gubernatorial candidacy of David B. Hill, weakening Cleveland's support.[94] The Republicans gained the upper hand in the campaign, as Cleveland's campaign was poorly managed by Calvin S. Brice and William H. Barnum, whereas Harrison had engaged more aggressive fundraisers and tacticians in Matt Quay and John Wanamaker.[95] The Cleveland campaign was further damaged by the desertion of many Mugwumps, who were disappointed by the lack of far-reaching civil service reforms.[96]

As in 1884, the election focused on the swing states of New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, and Indiana. Cleveland won every state he had carried in 1884 except for Indiana and his home state of New York, both of which were narrowly won by Harrison.[97] Though Cleveland won the nationwide popular vote by a margin of 0.8%, the loss of his home state's 36 electoral votes denied him re-election.[98] Republicans also won control of the House of Representatives, giving the party control of both houses of Congress for the first time since 1875.[99] Cleveland's loss made him the first incumbent president since Van Buren to be defeated in the general election.[100]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Donald Trump became the second to do so following his win in the 2024 election.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

definitionwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ In 1926, the principles of the Tenure of Office Act were ruled unconstitutional in the Supreme Court case of Myers v. United States, as the Supreme Court held the president could unilaterally remove executive branch officials.

References

[edit]reflist

- ^ Graff, pp. 31-33

- ^ a b Nevins, 146–147

- ^ Nevins, 147

- ^ Nevins, 152–153; Graff, 51–53

- ^ Welch, 29

- ^ a b Nevins, 153-154; Graff, 53–54

- ^ Nevins, 185–186; Jeffers, 96–97

- ^ Welch, 32–34

- ^ Tugwell, 93

- ^ Tugwell, 80

- ^ Summers, passim; Grossman, 31

- ^ Nevins, 156–159; Graff, 55

- ^ Nevins, 187–188

- ^ Welch, 33

- ^ a b Leip, David. "1884 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved January 27, 2008., "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved January 27, 2008.

- ^ "Cleveland's Cabinet". Newspapers.com. Alabama Beacon. 3 Mar 1885. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ "CLEVELAND'S CABINET". Newspapers.com. The Kansas City Times. 28 Feb 1885. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ "The Cabinet". Newspapers.com. St. Albans Daily Messenger. 28 Feb 1885. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ Graff, 68-71

- ^ Brodsky, 158; Jeffers, 149

- ^ Graff, 79

- ^ Jeffers, 170–176; Graff, 78–81; Nevins, 302–308; Welch, 51

- ^ Graff, 80–81

- ^ Nevins, 208–211

- ^ Graff, 83

- ^ Tugwell, 100

- ^ Nevins, 238–241; Welch, 59–60

- ^ Welch, 57–61

- ^ Tugwell, 130–134

- ^ Welch, 53–56

- ^ Glass, Andrew (11 February 2011). "Dept. of Agriculture gets Cabinet status, Feb. 11, 1889". Politico. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ a b c Nevins, 223–228

- ^ a b White, pp. 582–586

- ^ Welch, 78–79

- ^ U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Washington, D.C. "Our Documents: Interstate Commerce Act (1887)." Accessed 2010-10-19.

- ^ Breger, Marshall J.; Edles, Gary (2016). "Independent Agencies in the United States: The Responsibilities of Public Lawyers". Catholic University of America.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Welch, 79–80

- ^ Graff, 85

- ^ Nevins, 326–328; Graff, 83–84

- ^ Nevins, 300–331; Graff, 83

- ^ a b Nevins, 331–332; Graff, 85

- ^ "Cleveland and the Texas Seed Bill". Bill of Rights Institute. Retrieved 2021-07-24.

- ^ "Cleveland's Veto of the Texas Seed Bill". The Writings and Speeches of Grover Cleveland. New York: Cassell Publishing Co. 1892. p. 450. ISBN 0-217-89899-8.

- ^ Jeffers, 157–158

- ^ a b Nevins, 201–205; Graff, 102–103

- ^ a b Welch, 117–119

- ^ Nevins, 269

- ^ Tugwell, 110

- ^ a b Nevins, 273

- ^ Nevins, 277–279

- ^ The Writings and Speeches of Grover Cleveland. New York: Cassell Publishing Co. 1892. pp. 72–73. ISBN 0-217-89899-8.

- ^ Nevins, 286–287

- ^ Graff, 85-87

- ^ Welch, 83–86

- ^ Nevins, 280–282, Reitano, 46–62

- ^ Welch, 83

- ^ White, pp. 585–586

- ^ Nevins, 287–288

- ^ Nevins, 383–385

- ^ a b Graff, 88–89

- ^ White, pp. 586–588

- ^ Graff, 88

- ^ Pasco, Samuel (1902). "The Isthmian Canal Question as Affected by Treaties and Concessions". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 19: 24–45. doi:10.1177/000271620201900102. hdl:2027/hvd.32044081919094. JSTOR 1009813. S2CID 144487023. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ Nevins, 205; 404–405

- ^ Welch, 160

- ^ Nevins, 404–413

- ^ Charles S. Campbell Jr, "American Tariff Interests and the Northeastern Fisheries, 1883–1888." Canadian Historical Review 45.3 (1964): 212-228.

- ^ Zakaria, 80

- ^ Graff, 95-96

- ^ Welch, 166–169

- ^ Paul Kennedy, Samoan Tangle: A Study in Anglo-German-American Relations 1878–1900 (University of Queensland Press, 2013) online.

- ^ ?? Mark A. Berhow, American Seacoast Defenses A Reference Guide (1999) pp. 9–10

- ^ Endicott and Taft Boards at the Coast Defense Study Group website Archived 2016-02-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Berhow, p. 8

- ^ Civil War and 1870s defenses at the Coast Defense Study Group website Archived 2016-02-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Berhow, pp. 201–226

- ^ List of all US coastal forts and batteries at the Coast Defense Study Group website

- ^ ??? K. J. Bauer and Stephen Roberts, Register of Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1775-1990: Major Combatant (1991).

- ^ Bauer and Roberts, pp. 101-2, 133, 141–147

- ^ a b Welch, 65–66

- ^ Welch, 72–73

- ^ White, pp. 603–606

- ^ a b c Welch, 70; Nevins, 358–359

- ^ Graff, 206–207

- ^ White, p. 606

- ^ a b c d Brodsky, 141–142; Nevins, 228–229

- ^ Daniel J. Meador, "Lamar to the Court: Last Step to National Reunion" Supreme Court Historical Society Yearbook 1986: 27–47. ISSN 0362-5249

- ^ Willard L. King, Melville Weston Fuller—Chief Justice of the United States 1888–1910 (1950)

- ^ Nevins, 445–450

- ^ Ely, James W. (2003). The Fuller Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy. ABC-CLIO. pp. 26–31. ISBN 9781576077146. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- ^ Graff, 90–91

- ^ White, pp. 619–620

- ^ Nevins, 418–420

- ^ Nevins, 423–427

- ^ Tugwell, 166

- ^ White, p. 621

- ^ Leip, David. "1888 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved February 18, 2008., "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved February 18, 2008.

- ^ White, pp. 621–622

- ^ White, pp. 626–627

- ^ Charles W. Calhoun, Minority Victory: Gilded Age Politics and the Front Porch Campaign of 1888 (University Press of Kansas, 2008).