User:Daren Elsa NiBelly/sandbox

'Pataphysics (French: 'pataphysique) is a philosophy or media theory dedicated to studying what lies beyond the realm of metaphysics. The concept was coined by French writer Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), who defined 'pataphysics as "the science of imaginary solutions, which symbolically attributes the properties of objects, described by their virtuality, to their lineaments".[1]

A practitioner of 'pataphysics is a pataphysician or a pataphysicist.

Definitions

[edit]There are over one hundred differing definitions of pataphysics.[2] Some examples are shown below.

- "Pataphysics is the science of that which is superinduced upon metaphysics, whether within or beyond the latter’s limitations, extending as far beyond metaphysics as the latter extends beyond physics. … Pataphysics will be, above all, the science of the particular, despite the common opinion that the only science is that of the general. Pataphysics will examine the laws governing exceptions, and will explain the universe supplementary to this one.”[1]

- "'Pataphysics is patient; 'Pataphysics is benign; 'Pataphysics envies nothing, is never distracted, never puffed up, it has neither aspirations nor seeks not its own, it is even-tempered, and thinks not evil; it mocks not iniquity: it is enraptured with scientific truth; it supports everything, believes everything, has faith in everything and upholds everything that is.”[3] as cited in[2]

- "Pataphysics passes easily from one state of apparent definition to another. Thus it can present itself under the aspect of a gas, a liquid or a solid.”[4] as cited in[2]

- "Pataphysics "the science of the particular", does not, therefore, study the rules governing the general recurrence of a periodic incident (the expected case) so much as study the games governing the special occurrence of a sporadic accident (the excepted case). … Jarry performs humorously on behalf of literature what Nietzsche performs seriously on behalf of philosophy. Both thinkers in effect attempt to dream up a “gay science”, whose joie de vivre thrives wherever the tyranny of truth has increased our esteem for the lie and wherever the tyranny of reason has increased our esteem for the mad.”[5]

Etymology

[edit]The word pataphysics is a contracted formation, derived from the Greek, ἔπι (μετὰ τὰ φυσικά) (epi meta ta physika);[1] this phrase or expression means "that which is above metaphysics", and is itself a sly variation on the title of Aristotle's Metaphysics, which in Greek is "τὰ μετὰ τὰ φυσικά" (ta meta ta physika).

Jarry mandated the inclusion of the apostrophe in the orthography, 'pataphysique and 'pataphysics, "to avoid a simple pun".[1] The words pataphysician or pataphysicist and the adjective pataphysical should not include the apostrophe. Only when consciously referring to Jarry's science itself should the word pataphysics carry the apostrophe.[6] The term pataphysics is a paronym (considered a kind of pun in French) of metaphysics. Since the apostrophe in no way affects the meaning or pronunciation of pataphysics, this spelling of the term is a sly notation, to the reader, suggesting a variety of puns that listeners may hear, or be aware of. These puns include patte à physique ("physics paw"), as interpreted by Jarry scholars Keith Beaumont and Roger Shattuck, pas ta physique ("not your physics"), and pâte à physique ("physics pastry dough").

History

[edit]The term first appeared in print in the text of Alfred Jarry's play Guignol in the 28 April 1893 issue of L'Écho de Paris littéraire illustré, but it has been suggested that the word has its origins in the same schoolpranks at the lycée in Rennes that led Jarry to write Ubu Roi.[7] Jarry considered Ibicrates and Sophrotatos the Armenian as the fathers of this "science".[8]

The Collège de 'Pataphysique

[edit]The Collège de 'Pataphysique, founded in 1948 in Paris, France,[9] is a "society committed to learned and inutilious research".[10] (The word 'inutilious' is synonymous with 'useless'.) The motto of the college is Latin: Eadem mutata resurgo ("I arise again the same though changed"), and its current Vice-Curator is Her Magnificence Lutembi - a crocodile.[11] The permanent head of the college is the fictional Dr. Faustroll (Inamovable Curator), with assistance of the equally fictional Bosse-de-Nage (Starosta).[12] The Vice-Curator is as such the "first and most senior living entity" in the college's hierarchy.[13] Publications of the college, generally called Latin: Viridis Candela ("green candle"),[14] include the Cahiers, Dossiers and the Subsidia Pataphysica.[15][16] The college stopped its public activities between 1975 and 2000, referred to as its occultation.[17][18] Notable members have included Noël Arnaud, Luc Étienne, Latis, François Le Lionnais, Jean Lescure, Raymond Queneau, Boris Vian, Eugène Ionesco, Jacques Carelman, Joan Miró, Man Ray, Max Ernst, Julien Torma, Roger Shattuck, Groucho, Chico and Harpo Marx, Baron Jean Mollet, Irénée Louis Sandomir, Opach and Marcel Duchamp.[19] The Oulipo began as a subcommittee of the college.[20][21]

Offshoots of the Collège de 'Pataphysique

[edit]Although France had been always the centre of the pataphysical globe, there are followers up in different cities around the world. In 1966 Juan Esteban Fassio was commissioned to draw the map of the Collège de 'Pataphysique and its institutes abroad. In the 1950s, Buenos Aires in the Western Hemisphere and Milan in Europe were the first cities to have pataphysical institutes. London, Edinburgh, Budapest, and Liège, as well as many other European cities, caught up in the sixties. In the 1970s, when the Collège de 'Pataphysique occulted, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland, Canada, The Netherlands, and many other countries showed that the internationalization of pataphysics was irreversible. During the Communist Era, a small group of pataphysicists in Czechoslovakia started a journal called PAKO, or Pataphysical Collegium.[22] Alfred Jarry's plays had a lasting impression on the country's underground philosophical scene. A Pataphysics Institute opened in Vilnius, Lithuania in May 2013: Patafizikos instituto atidarymas Vilniuje.

London Institute of 'Pataphysics

[edit]The London Institute of 'Pataphysics was established in September 2000 to promote pataphysics in the English-speaking world. The institute has various publications, including a journal and has six departments:[23]

- Bureau for the Investigation of Subliminal Images

- Committee for Hirsutism and Pogonotrophy

- Department of Dogma and Theory

- Department of Potassons

- Department of Reconstructive Archaeology

- The Office of Patentry

The institute also contains a pataphysical museum and archive and organised the Anthony Hancock Paintings and Sculptures exhibition in 2002.[24]

Musée Patamécanique

[edit]Musée Patamécanique is a private museum located in Bristol, Rhode Island.[25] Founded in 2006, it is open by appointment only to friends, colleagues, and occasionally to outside observers. The museum is presented as a hybrid between an automaton theater and a cabinet of curiosities and contains works representing the field of Patamechanics, an artistic practice and area of study chiefly inspired by Pataphysics. Examples of exhibits include a troop of singing animatronic Chipmunks, A Time Machine, which the museum claims to be the world’s largest automated Phenakistascope, an olfactory Clock, a chandelier of singing animatronic nightingales, an Undigestulator (a device that purportedly reconstitutes digested foods), A Peanuts Enlarger, A Syzygistic Oracle, The Earolin (a 24 inch tall holographic ear that plays the violin), and a machine for capturing the dreams of bumble bees.[26]

Concepts

[edit]- Clinamen

- A clinamen is the unpredictable swerve of atoms that Bök calls “the smallest possible aberration that can make the greatest possible difference”.[27] An example is Jarry’s merdre, a swerve of French: merde ("shit").[28]

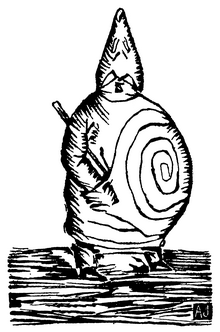

The Grand Gidouille on Ubu's belly is a symbol of pataphysics - Antinomy

- An antinomy is the mutually incompatible. It represents the duality of things, the echo or symmetry, the good and the evil at the same time. Hugill mentions various examples including the plus minus, the faust-troll, the haldern-ablou, the yes-but, the ha-ha and the paradox.[29]

- Syzygy

- The syzygy originally comes from astronomy and denotes the alignment of three celestial bodies in a straight line. In a pataphysical context it is the pun. It usually describes a conjunction of things, something unexpected and surprising. Serendipity is a simple chance encounter but the syzygy has a more scientific purpose. Bök mentions Jarry suggesting that the fall of a body towards a centre might not be preferable to the ascension of a vacuum towards a periphery.[30][31]

- Absolute

- The absolute is the idea of a transcended reality.[32]

- Anomaly

- An anomaly represents the exception. Jarry said that "pataphysics will examine the laws governing exceptions, and will explain the universe supplementary to this one".[1] Bök calls it “the repressed part of a rule which ensures that the rule does not work”.[33][34]

- Pataphor

- A pataphor is an unusually extended metaphor based on 'pataphysics. As Jarry claimed that pataphysics exists "as far from metaphysics as metaphysics extends from regular reality", a pataphor attempts to create a figure of speech that exists as far from metaphor as metaphor exists from non-figurative language.[35]

Pataphysical calendar

[edit]The pataphysical calendar[36] is a variation of the Gregorian calendar. The Collège de 'Pataphysique created the calendar[37] in 1949.[38] The pataphysical era (E.P.) started on 8 September 1873 (Jarry's birthday). When converting pataphysical dates to Gregorian dates, the appendage (vulg.) for vulgate is added.[38]

The week starts on a Sunday. Every 1st, 8th, 15th and 22nd is a Sunday and every 13th day of a month falls on a Friday (see Friday the 13th). Each day is assigned a specific name or saint. For example, the 27 Haha (1 November vulg.) is called French: Occultation d'Alfred Jarry or the 14 Sable (14 December vulg.) is the day of French: Don Quichote, champion du monde.[39]

The year has a total of 13 months each with 29 days. The 29th day of each month is imaginary with two exceptions:[39]

- the 29 Gidouille (13 July vulg.) is always non-imaginary

- the 29 Gueules (23 February vulg.) is non-imaginary during leap years

The table below shows the names and order of months in a pataphysical year with their corresponding Gregorian dates and approximate translations or meanings by Hugill.[38]

| Month | Starts | Ends | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolu | 8 September | 5 October | Absolute |

| Haha | 6 October | 2 November | Ha Ha |

| As | 3 November | 30 November | Skiff |

| Sable | 1 December | 28 December | Sand or heraldic black |

| Décervelage | 29 December | 25 January | Debraining |

| Gueules | 26 January | 22/23 February | Heraldic red or gob |

| Pédale | 23/24 February | 22 March | Bicycle pedal |

| Clinamen | 23 March | 19 April | Swerve |

| Palotin | 20 April | 17 May | Ubu's henchmen |

| Merdre | 18 May | 14 June | Pshit |

| Gidouille | 15 June | 13 July | Spiral |

| Tatane | 14 July | 10 August | Shoe or being worn out |

| Phalle | 11 August | 7 September | Phallus |

For example:

- 8 September 1873 (vulg.) = 1 Absolu 1

- 1 January 2000 (vulg.) = 4 Décervelage 127

- 10 November 2012 (vulg.)(Saturday) = 8 As 140 (Sunday)

See also Bob Richmond's comments on the calendar and the French Wikipedia article.

Influences

[edit]In the 1960s 'pataphysics was used as a conceptual principle within various fine art forms, especially pop art and popular culture. Works within the pataphysical tradition tend to focus on the processes of their creation, and elements of chance or arbitrary choices are frequently key in those processes. Select pieces from the artist Marcel Duchamp[40] and the composer John Cage[41] characterize this. At around this time, Asger Jorn, a pataphysician and member of the Situationist International, referred to 'pataphysics as a new religion.[42] Rube Goldberg and Heath Robinson were artists who contrived machines of a pataphysical bent.

In literature

[edit]- The authors Raymond Queneau, Jean Genet, Eugène Ionesco, Boris Vian, Rene Daumal and Jean Ferry have described themselves as following the pataphysical tradition.

- 'Pataphysics and pataphysicians feature prominently in several linked works by science fiction writer Pat Murphy.

- The philosopher Jean Baudrillard is often described as a pataphysician and identified as such for some part of his life.[43]

- American writer Pablo Lopez has developed an extension of 'pataphysics called the pataphor.

In music

[edit]- The debut album by Ron 'Pate's Debonairs, featuring Reverend Fred Lane (his first appearance on vinyl), is titled Raudelunas 'Pataphysical Revue (1977), a live theatrical performance. A review in The Wire magazine said, "No other record has ever come as close to realising Alfred Jarry's desire 'to make the soul monstrous' – or even had the vision or invention to try".[44] 'Pate (note the 'pataphysical apostrophe) and Lane were central members in the Raudelunas art collective in Tuscaloosa, Alabama.

- Professor Andrew Hugill, of De Montfort University, is a practitioner of pataphysical music. He curated Pataphysics, for the Sonic Arts Network's CD series,[45] and in 2007 some of his own music was issued by UHRecordings under the title Pataphysical Piano; the sounds and silences of Andrew Hugill.[46]

- British progressive rock band Soft Machine were self described at "the Official Orchestra of the College of Pataphysics", and featured the two songs "Pataphysical Introduction" parts I and II on their 1969 album Volume Two.

- Japanese psychedelic rock band Acid Mothers Temple refer to the topic on their 1999 release Pataphisical Freak Out MU!!.

- Autolux, LA based noise pop band, have a song "Science Of Imaginary Solutions" in their second album Transit Transit.

- "'Pataphysical science" is mentioned as a course of study for Maxwell Edison's first victim, "Joan", in the song "Maxwell's Silver Hammer" on the Beatles album, Abbey Road.

In visual art

[edit]- American artist Thomas Chimes developed an interest in Jarry's pataphysics, which became a lifelong passion, inspiring much of the painter's creative work.

- The League of Imaginary Scientists, a Los Angeles-based art collective specializing in pataphysics-based interactive experiments. In 2011 they exhibited a series of projects at Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles.

- James E. Brewton, Philadelphia artist (1930-1967), with interest in Jarry & pataphysics [1]

- Slought, arts organization for cultural and socio-political change in Philadelphia, the world, and the cloud, with programs on Jarry and pataphysics [2][3][4]

Pataphor

[edit]The pataphor (Spanish: patáfora, French: pataphore), is a term coined by writer and musician Pablo Lopez, for an unusually extended metaphor based on Alfred Jarry's "science" of pataphysics. As Jarry claimed that pataphysics existed "as far from metaphysics as metaphysics extends from regular reality", a pataphor attempts to create a figure of speech that exists as far from metaphor as metaphor exists from non-figurative language. Whereas a metaphor is the comparison of a real object or event with a seemingly unrelated subject in order to emphasize the similarities between the two, the pataphor uses the newly created metaphorical similarity as a reality on which to base itself. In going beyond mere ornamentation of the original idea, the pataphor seeks to describe a new and separate world, in which an idea or aspect has taken on a life of its own.[47][48]

Like pataphysics itself, pataphors essentially describe two degrees of separation from reality (rather than merely one degree of separation, which is the world of metaphors and metaphysics). The pataphor may also be said to function as a critical tool, describing the world of "assumptions based on assumptions", such as belief systems or rhetoric run amok. The following is an example.

"Non-figurative:

- Tom and Alice stood side by side in the lunch line.

Metaphor

- Tom and Alice stood side by side in the lunch line; two pieces positioned on a chessboard.

Pataphor

- Tom took a step closer to Alice and made a date for Friday night, checkmating. Rudy was furious at losing to Margaret so easily and dumped the board on the rose-colored quilt, stomping downstairs."[49]

Thus, the pataphor has created a world where the chessboard exists, including the characters who live in that world, entirely abandoning the original context.[49]

The pataphor has been subject to commercial interpretations,[50] usage in speculative computer applications,[51] applied to highly imaginative problem solving methods[52] and even politics on the international level[53] or theatre The Firesign Theatre (a comedy troupe whose jokes often rely on pataphors). There is a band called Pataphor[54] and an interactive fiction in the Interactive Fiction Database called "PataNoir," based on pataphors.[55][56]

Pataphors have been the subject of art exhibits, as in Tara Strickstein's 2010 "Pataphor" exhibit at Next Art Fair/Art Chicago.[57]

There is also a book of pataphorical art called Pataphor by Dutch artist Hidde von Schie.[58]

It is worth noting that a pataphor is not the traditional metaphorical conceit but rather a set of metaphors built upon an initial metaphor, obscuring its own origin rather than reiterating the same analogy in myriad ways.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Jarry 1996, p.21.

- ^ a b c Brotchie et al. 2003

- ^ “Épanorthose sur le Clinamen moral”, Cahiers du Collège de ‘Pataphysique, 21, 22 Sable 83 (29 December 1955 vulg.)

- ^ Patafluens 2001, Istituto Patafisico Vitellianese, Viadana, 2002

- ^ Bök 2002, p.9.

- ^ Hugill 2012, p.8.

- ^ Hugill 2012, p.207.

- ^ Hugill 2012, p.20.

- ^ Brotchie 1995, p.11.

- ^ Brotchie 1995, p.77.

- ^ Hugill 2012, p.38.

- ^ Brotchie 1995, p.39.

- ^ Hugill 2012, p.113.

- ^ Hugill 2012, p.123.

- ^ List of publications by the Collège de 'Pataphysique

- ^ Brotchie 1995, p.102-104.

- ^ Hugill 2012, p.39.

- ^ Brotchie 1995, p.31.

- ^ Brotchie 1995, p.10-31.

- ^ Motte, Warren (2007). Oulipo: a primer of potential literature. Dalkey Archive Press. p. 1. ISBN 1-56478-187-9.

- ^ Brotchie 1995, p.22.

- ^ Hugill 2012, p.48.

- ^ Webpage of the London Institute of 'Pataphysics

- ^ Anthony Hancock Paintings and Sculptures exhibition

- ^ Webpage of Musée Patamécanique

- ^ Musée Patamécanique exhibition

- ^ Bök 2002, p.43-45.

- ^ Hugill 2012, p.15-16.

- ^ Hugill 2012, p.9-12.

- ^ Bök 2002, p.40-43.

- ^ Hugill 2012, p.13-15.

- ^ Hugill 2012, p.16-19.

- ^ Bök 2002, p.38-40.

- ^ Hugill 2012, p.12-13.

- ^ "Paul Avion's Pataphor"

- ^ (in French) Electronic version of the pataphysical calendar

- ^ (in French) Reference number 1230, published 1954, as listed in the college's catalogue

- ^ a b c Hugill 2012, p.21-22.

- ^ a b Brotchie 1995, p.45-54.

- ^ Hugill 2012, p.55.

- ^ Hugill 2012, p.51-52.

- ^ Asger Jorn's "Pataphysics: A Religion in the Making"

- ^ The Jean Baudrillard Reader. Redhead, Steve, Columbia University Press, 2008, pp. 6–7. 1 March 2008. ISBN 978-0-231-14613-5. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- ^ Baxter, Ed (September 1998). "100 Records That Set The World On Fire . . . While No One Was Listening". The Wire. pp. 35–36.

- ^ "Music". Andrew Hugill. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ "Pataphysical Piano – The sounds and silences of Andrew Hugill by various artists". Uhrecordings.co.uk. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ (Spanish) Luis Casado, Pataphors And Political Language, El Clarin: Chilean Press, 2007

- ^ The Cahiers du Collège de 'Pataphysique, n°22 (December 2005), Collège de 'Pataphysique

- ^ a b "Pataphor / Pataphors : Official Site : closet 'pataphysics". Pataphor.com. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ "Coke… it's the Real Thing « Not A Real Thing". Notarealthing.com. 31 January 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ "i l I .P o s e d p hi l . o s o ph y". Illposed.com. 23 February 2006. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ Findlay, John (3 July 2010). "Wingwams: Playing with pataphors". Wingwams.blogspot.com. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ "El Clarín de Chile - Patafísica y patáforas". Elclarin.cl. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

{{cite web}}: soft hyphen character in|title=at position 9 (help) - ^ "Pataphor". Pataphor.bandcamp.com. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ "PataNoir - Details". Ifdb.tads.org. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ "Parchment". Iplayif.com. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ ArtTalkGuest. "Tara Strickstein's "Pataphor" at Next Art Fair/Art Chicago 2010 | Art Talk Chicago". Chicagonow.com. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ "Pataphor - Hidde van Schie". Tentrotterdam.nl. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

Bibliography

[edit]- Jones, Andrew. Plunderphonics,Pataphysics & Pop Mechanics: An Introduction to Musique Actuelle. SAF Publishing Ltd, 1995.

- Beaumont, Keith (1984). Alfred Jarry: A Critical and Biographical Study. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-01712-X.

- Bök, Christian (2002). 'Pataphysics: The Poetics of an Imaginary Science. Northwestern University Press. ISBN 978-0-8101-1877-5.

- Brotchie, Alistair, ed. (1995). A True History of the College of ’Pataphysics. Atlas Press. ISBN 0-947757-78-3.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Alistair Brotchie, Stanley Chapman, Thieri Foulc and Kevin Jackson, ed. (2003). 'Pataphysics: definitions and citations. London: Atlas Press. ISBN 1-900565-08-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Brotchie, Alistair (2011). Alfred Jarry: A Pataphysical Life. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-01619-3.

- Clements, Cal (2002). Pataphysica. iUnivers, Inc. ISBN 0-595-23604-9.

- Hugill, Andrew (2012). 'Pataphysics: A useless guide. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-01779-4.

- Jarry, Alfred (1980). Gestes et opinions du Docteur Faustroll, pataphysicien (in French). France: Gallimard. ISBN 2-07-032198-3.

- Jarry, Alfred (1996). Exploits and opinions of Dr. Faustroll, pataphysician. Exact Change. ISBN 1-878972-07-3.

- Jarry, Alfred (2006). Collected works II - Three early novels. London: Atlas Press. ISBN 1-900565-36-6.

- Shattuck, Roger (1980). Roger Shattuck's Selected Works of Alfred Jarry. Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-5167-1.

- Taylor, Michael R. (2007). Thomas Chimes Adventures in 'Pataphysics. Philadelphia Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87633-253-5.

- Vian, Boris (2006). Stanley Chapman (ed.). 'Pataphysics? What's That?. London: Atlas Press. ISBN 1-900565-32-3.

- Morton, Donald. "Pataphysics of the Closet." Transformation: Marxist Boundary Work in Theory, Economics, *Politics and Culture (2001): 1-69.

- Powrie, Phil. "René Daumal and the pataphysics of liberation." Neophilologus 73.4 (1989): 532-540.

External links

[edit]- (in French) Collège de ’Pataphysique

- London Institute of 'Pataphysics

- Patakosmos, the complete ‘Pataphysics Institute map of the world

- Musée Patamécanique

- (in Italian) Autoclave di Estrazioni Patafisiche

- (in Dutch) De Nederlandse Academie voor 'Patafysica

- (in German) Institut für 'Pataphysik

- 'Marcel Duchamp and 'Pataphysics'

- Pataphysics by Jean Baudrillard (translated by Drew Burk)

- (in Spanish) Alfred Jarry y el Collége de Pataphysique; la Ciencia de las soluciones imaginarias - Adolfo Vásquez Rocca[dead link]

- (in Italian) Ubuland, information on Italian pataphysics.

- UbuWeb, resource of pataphysical, avant-garde, ethnopoetic and outsider arts.

- (in French) Calendrier 'Pataphysique, Gregorian to 'Pataphysical calendar converter