User:Chlostall/sandbox

| This is a user sandbox of Chlostall. You can use it for testing or practicing edits. This is not the sandbox where you should draft your assigned article for a dashboard.wikiedu.org course. To find the right sandbox for your assignment, visit your Dashboard course page and follow the Sandbox Draft link for your assigned article in the My Articles section. |

African slaves owned by Native Americans was the practice owning Africans as property during the colonial period and early establishment of the United States. Although, chattel slavery was a primarily European institution several North American indigenous groups adopted slave ownership for several purposes, the predominant as a tactic to assimilate into European colonial society. Most of the indigenous tribes who participated in this practice resided in the Southwest where white European infrastructure thrive off of slave ownership.

Background

[edit]The interactions between African Slaves and Native Americans in antebellum United States is a complicated portion of history as slavery played a significant role in the creation and construction of America. This slavery institution relied largely on the enslavement of Africans owned by white European colonists and later white Americans after the United States gained independence from Great Britain.[1] However, white men were not the only slave holders in America as over time, some Native American tribes began to keep slaves as well, specifically the Five Civilized Tribes (Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole).[2]

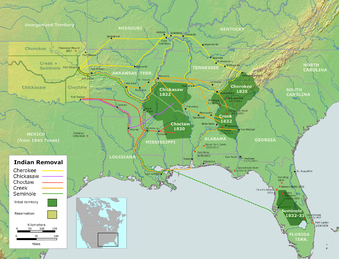

The earliest record of African and Native American contact is not well documented and scholars contest when the two groups first had contact. Some scholars argue that because of similarities between some African and Native American cultural artifacts, the two groups likely had transatlantic encounters before European discovery of the Americas.[1] This rhetoric cannot however be proved, and yet by the 18th century, African slaves and Native Americans had become a commonplace in colonial America. Native Americans and Africans have many interactions as oppressed communities.[3] Before the jump start of the Atlantic Slave Trade, European settlers enslaved some Native Americans, and major slave colonies such as Virginia and South Carolina enslaved thousands (30,000-53,000) Native Americans in the late 1600s and early 1700s.[4] African slaves quickly replaced Native American indentured servitude and eventually many Native Americans were moved off their land and forced to move westward. There are many examples of this forced removal, but one of the most famous was the Trail of Tears that forced peoples of the Cherokee nation to move westward to Oklahoma. [1]

African chattel slavery by Native Americans in the American Southeast

[edit]In an effort to avoid removal, some Native American tribes attempted to assimilate into white European society through strategies such as formal schooling, adopting Christianity, moving off the reservation, or even owning slaves. The Five Civilized Tribes implemented some of these practices which they have seen as beneficial; they were working to get along with the Americans to keep their territory. These 5 nations made the largest efforts of all the Native American peoples to assimilate into white society adoption of slavey was one of them.[2] They were the most receptive to whites pressures to adopt European cultures. The pressures from European Americans to assimilate, the economic shift of furs and deerskins, and the government's continued attempts to civilize native tribes in the south led to them adopting an economy based on agriculture.[3] Slavery itself was not a new concept to indigenous American peoples as in inter-Native American conflict tribes often kept prisoners of war, but these captures often replaced slain tribe members.[4] Native American “versions” of slavery prior to European contact came nowhere close to fitting the European definition of slavery as Native Americans did not originally distinguish between groups of people based on color, but rather traditions.[1] There are conflicting theories as to what caused the shift between traditional Native American servitude to the oppressive racialized enslavement the Five Civilized tribes adopted. One theory is the civilized tribes adopted slavery as means to defend themselves from federal pressure believing that it would help them maintain their southern lands.[2] Another narrative postulates that Native Americans began to feed into the European belief that Africans were somehow inferior to whites and themselves.[5] Some indigenous nations such as the Chickasaws and the Choctaws began to embrace the concept that African bodies were property, and equated blackness to hereditary inferiority.[6] In either case “The system of racial classification and hierarchy took shape as Europeans and Euro-Americans sought to subordinate and exploit Native Americans' and Africans' land, bodies, and labor.[1] Whether strategically or racially motivated the slave trade promoted Interactions Between The Five Civilized Tribes and African Slaves which led to new power relations among Native societies, elevating groups such as the Five Civilized Tribes to power and serving, ironically, to preserve native order.[7]

Slavery in the Indian Territory

[edit]In the 1830s, all of the Five Civilized Tribes were relocated, many of them forcibly to the Indian Territory (later, the state of Oklahoma). The institution of owning enslaved Africans came with them. Of the estimated 4,500 to 5,000 negroes who formed the slave class in the Indian Territory by 1839, the great majority were in the possession of the mixed bloods.[2]

Other responses to African chattel slavery by Native Americans

[edit]Tensions varied between African American and Native Americans in the south, as each nation dealt with the ideology behind enslavement of Africans differently.[3] In the late 1700s and 1800s, some Native American nations gave sanctuary to runaway slaves while others were more likely to capture them and return them to their white masters or even re-enslave them.[5] Still, others incorporated runaway slaves into their societies, sometimes resulting in intermarriage between the Africans and the Native American, which was a common place among the Creek and Seminole.[8][1] Although, some Native Americans may have had a strong dislike of slavery, because they too were seen as a people of a subordinate race than white men of European descent, they lacked the political power to influence the racialistic culture that pervaded the Non-Indian South.[1] It is unclear if Native American slaveholders sympathized with African American slaves as fellow people of color, class more than race may be a more useful prism through which to view masters of color.[2] Missionary work was an efficient method the United States used to persuade Native Americans to accept European methods of living[2] Missionaries vociferously denounced Indian removal as cruel, oppressive, and feared such actions would push Native Americans away from converting.[9]

Interestingly, these same missionaries reported that Native American slave owners were brutal and indulgent masters, even though accounts of Indian freedmen gave different accounts of being treated relatively well without tyrannical treatment.[8] The earliest record of African and Native American contact occurred in April 1502, when Spanish explorers brought an African slave with them and encountered a band.[10][better source needed] Thereafter, Native Americans interacted with enslaved Africans and African Americans in every way possible.[clarification needed][11][12] In the early colonial days, Native Americans were enslaved along with Africans, and both often worked with European indentured laborers.[11][13][14] "They worked together, lived together in communal quarters, produced collective recipes for food, shared herbal remedies, myths and legends, and in the end they intermarried."[12][15] Because both races were non-Christian, Europeans considered them other and inferior to Europeans. They worked to make enemies of the two groups. In some areas, Native Americans began to slowly absorb white culture.[11]

Five Civilized Tribes adoption of chattel slavery

[edit]The adoption and adaptation of Euro-American institutions in cruel irony did nothing to shield Native Americans from U.S. domination and created divisions within the tribes themselves.[16] Benjamin Hawkins, Superintendent of the tribes south of the Ohio River from the late eighteenth century through the early nineteenth, encouraged the major Southeast tribes to adopt chattel slavery in order to have labor for plantations and large-scale agricultural production, as part of their assimilation of European-American ways.[17] The pressures from European Americans to assimilate, the economic shift of furs and deerskins, and the government's continued attempts to civilize native tribes in the south led to them adopting an economy based on agriculture.[18] Some of what would become known as the "Five Civilized Tribes" had also acquired African American slaves as plunder from during the Revolutionary War which was allowed by their British allies."[18] The Five Civilized Tribes adopted some practices which they saw as beneficial; they were working to get along with the Americans and to keep their territory. The civilized tribes adopted slavery as means to defend themselves from federal pressure believing that it would help them maintain their southern lands.[16] Tensions varied between African American and Native Americans in the south, as by the early 1800s sanctuary for runaway slaves changed sometimes slaves had a 50% chance that Native Americans may capture them and return them to their white masters or even re-enslave them.[18] In contrast to white slaveholders, Native American slaveholders didn't use justifications for slavery nor maintain a fictional view of seeing slaves as part of the family.[18] However, the status of individual slaves could change if captors adopted or married African American slaves, but enslaved people as a whole had always been linked to their lack of kin ties.[18] Though some Native Americans had a strong dislike of slavery they lacked political power and a paternalist culture that pervaded the non-Indian south; as white men were seen as absolute masters in their households.[18] It is unclear if Native American slaveholders sympathized with African American slaves as fellow people of color, class more than race may be a more useful prism through which to view masters of color.[18] Missionaries and supporters of the American Board vociferously denounced Indian removal as cruel, oppressive, and feared such actions would push Native Americans away from converting.[19] Christianity emerged as an important fault line separating some Native Americans and African Americans as most African Americans by the early 1800s had accepted the teachings of missionaries while few Native Americans particularly the Choctaw and Chickasaw in the south converted and still practiced traditional spiritual beliefs.[18][19] Many Native Americans saw the attempts of missionization as a part U.S. expansion.[19] Furthermore, not all African Americans in Indian Territory were slaves, as some were free.[18] An example of this would be a town on the eastern part of the Choctaw Nation was home to a diverse community that included free African Americans as well as people of mixed African-Choctaw descent.[18] In Indian Territory these communities were not a rarity and complicated the taking of censuses commissioned by the U.S. government.[18] In 1832, census takers commissioned by the U.S. government in Creek country struggled to categorize the diverse group of people who resided there; unsure how to count African American wives of Creek men, nor where to place people of mixed African-Native descent.[18]

The federal government's expulsion of the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Creek (Muscogee) tribes opened the door to the rapid growth of plantation slavery across the "Deep South", but Indian removal also pushed chattel slavery westward, setting the stage for more conflicts.[16] Unlike other tribes that were physically forced to move out of the "Deep South" the government actively sought to have the Choctaw and Chickasaw nations forcefully unified governmentally.[16] The Choctaw and Chickasaw saw each other as different people and were bitter enemies in the 1700s, but in 1837 a treaty was made unifying the two tribes.[16] The two tribes agreed to the union but a treaty made in 1855 allowed the two tribes to separate as different governments.[16]

Cherokee

[edit]The Cherokee was the tribe that held the most slaves. In 1809, they held nearly 600 enslaved blacks.[11] This number increased to almost 1,600 in 1835, and to around 4,000 by 1860, after they had removed to Indian Territory.[11] Cherokee populations for these dates are: 12,400 in 1809;, 16,400 in 1835; and 21,000 in 1860.[11] The proportion of Cherokee families who owned slaves did not exceed ten percent, and was comparable to the percentage among white families across the South, where a slaveholding elite owned most of the laborers.[11] In the 1835 census, only eight percent of Cherokee households contained slaves, and only three Cherokee owned more than 50 slaves.[11] Joseph Vann had the most, owning 110 like other major planters.[11] Of the Cherokee who owned slaves, 83 percent held fewer than 10 slaves.[11] Of the slave-owning families, 78 percent claimed some white ancestry.[11]

In 1827 the Cherokee developed a constitution, which was part of their acculturation. It prohibited slaves and their descendants (including mixed-race) from owning property, selling goods or produce to earn money; and marrying Cherokee or European Americans. It imposed heavy fines on slaveholders if their slaves consumed alcohol.[11] No African Americans, even if free and of partial Cherokee heritage, could vote in the tribe.[11] If a mother was of partial African descent, her children could not vote in the tribe, regardless of the father's heritage; the Cherokee also prohibited any person of Negro or mulatto parentage from holding an office in the Cherokee government.[11][20] Such laws reflected state slavery laws in the Southeast, but Cherokee laws did not impose as many restrictions on slaves nor were they strictly enforced.[11] In their constitution, the Cherokee council made strong efforts to regulate the marrying of Cherokee women to white men, but made little effort to control whom Cherokee men chose to marry or have a union with.[21] It was not uncommon nor rampant for Cherokee men to have unions with African American women who were slaves, but there was little incentive for them to legalize the union as children born to slave women or any woman of African descent were not seen as Cherokee citizens at the time due to the rule of The Cherokee Constitution.[20][21] Some sexual relationships between Cherokee men and African American women were also informal so prohibitions on marriage wouldn't affect them.[21] The lack of legal prohibitions on such unions points to the unwillingness of lawmakers, many of whom belonged to slaveholding families, to infringe on the prerogatives of masters over slaves or to constrain the sexual behavior of men in the tribe.[21] However, the Cherokee did not recognize marriages between African Americans and Cherokee citizens and declared people of African descent as forbidden marriage partners in effort to keep a divide between the two racial groups.[21] Though few cases on record indicate such unions did occur, in 1854 a Cherokee named Cricket was charged with taking a colored wife, and for unclear reasons the Cherokee courts tried him and acquitted him.[21] It is speculated that maybe the court was attempting to express disapproval, the relationship may have been considered less formal, or etc.[21] The "1855 Act" made no room for formal relationships between African Americans and Cherokee citizens and was partially derived from the "1839 Act" preventing amalgamation with colored persons, which was still in effect but did not prevent such unions from occurring.[21] By 1860 the slave population in the Cherokee nation made up 18% of the entire population of the nation with most slaves being culturally Cherokee, only spoke the Cherokee language, and were immersed in Cherokee traditions.[20] The Cherokee also had no laws the manumission of slaves; manumission was given for numerous reasons.[22][23]

Choctaw

[edit]The Choctaw bought many of their slaves from Georgia.[19] The Choctaw held laws in their constitution which also mirrored the "Deep South".[16] The Choctaw in Indian Territory did not allow anyone with African heritage to hold office even if they were of partial heritage.[16] The Choctaw 1840 constitution also didn't allow free African Americans to settle in the Choctaw nation meaning they were not allowed to own or obtain land, but white men who could get permission in writing from the Chief or the United States Agent to reside in the Choctaw nation.[16][19] The Choctaw nation further barred those of partial African heritage from being recognized as Choctaw citizens, but a white man married to a Choctaw woman would be eligible for naturalization.[16] In response to proslavery ideology in the Native American nations creating a climate of animosity toward free African Americans the Choctaw General Council enacted legislation in October 1840 that mandated the expulsion of all free black people "unconnected with the Choctaw & Chickasaw blood" by March 1841.[19] Those who remained were at risk of being sold at an auction and enslaved for life.[19] W.P.A. interviews conducted varied among former slaves of the Choctaw tribe, one former slave Edmond Flint asserted that his bondage by the Choctaw didn't differ from being a slave under a white household, but indicated that within the Choctaw there were humane and inhumane masters[18] Choctaw slaveholders and those who were not slaveholders were a major focus for missionaries wanting to convert those who weren't Christian.[19] One Methodist newspaper in 1829 stated,

What account will our people render to God if, through their neglect, this people, now ripe for the gospel, should be forced into the boundless wilds beyond the Mississippi, in their present state of ignorance?[19]

The Choctaw did allow their slaves to worships at Christian missions.[19] For Africans rebuilding their religious lives in the Native American nations sustained a sense of connection to the kin and communities that had been left behind.[19] Missionaries were able to establish mission churches and school in the Choctaw lands with permission from the tribe's leaders, but the issues of slavery created aversion between the Choctaw and the missionaries.[19] The missionaries argued that human bondage didn't reflect a Christian society, and believed it highlighted native people's laziness, cruelty, and resistance to "civilization."[19] In the 1820s a heated debate over to allow slaveholding Choctaw into mission churches occurred, but a final decision was made with missionaries not wanting to alienate slaveholding Native Americans as potential converts and so received them at prayer meetings and granted church membership with the hope of enlightening them through discussion and prayer.[19] During this time, missionaries did see Choctaws and African Americans as racially and intellectually inferior with converted Africans as intellectually and morally sounder than non-Christian Native Americans.[19] Cyrus Kingsbury a leader of the American Board believed him and the other missionaries had brought civilization to the Choctaw whom he deemed as uncivilized people.[19] A few Choctaw slaveholders believed that having their slaves learn how to read the Bible would cause them to become spoiled slaves, and this added to the persistent mistrust the Choctaw had for missionaries.[19] One Choctaw slaveholder Israel Folsom informed Kingsbury that the Folsom family would no longer attend Kingsbury's church because of its antislavery position.[19] The Choctaw grew tired of the missionaries condescending attitudes or questioned pedagogical approach toward both Native American pupils and African worshippers, they withdrew their children, slaves, and financial support from the mission schools and churches.[19] The Choctaw masters whether they converted to Christianity or not did not rely on religion as a weapon of control on in interaction with their slaves, but did regulate where enslaved peoples could have religious gatherings.[19] In 1850 the U.S. Congress made its most dramatic legislative move against free African Americans in the United States with its approval of the Fugitive Slave Act, which added to the tensions free African Americans felt in the Choctaw Nation.[19] However, even with Choctaw lawmakers determined measures to separate the Choctaw from free African Americans some free African Americans remained in the nation undisturbed.[19] In 1860 census takers from Arkansas documented several households that were dominantly African American in the Choctaw nation.[19] The kidnappings of free African Americans by white men became a serious threat even for those in Native American nations.[19] Though paternalism sometimes motivated prominent Native Americans to protect free black people, political leaders and slaveholders generally viewed free African Americans as magnets for white thieves and thus a menace to slaveholders and national security.[19] In 1842 Choctaw Peter Pitchlynn wrote to U.S. secretary of war, complaining about the "armed Texans" who charged into Choctaw country and kidnapped the Beams family; citing it as evidence white Americans disregard for Native American sovereignty.[19] The Beams family case went on from the 1830s to 1856 when the Choctaw court ruled that the family was indeed a free black family.[19]

Chickasaw

[edit]The Chickasaw also held similar laws mimicking the culture of the American south.[16] After the Revolutionary War the Chickasaw like many other tribes were the targets of assimilation, they were pressed into giving up their trading of deerskins, and communal hunting grounds.[16] The secretary of war Henry Knox under George Washington set two interrelated goals: peaceful land acquisitions and programs focused on assimilating Native Americans in the south.[16] The Chickasaw became familiarized with chattel slavery through the British and French allies, and began to adopt this form of slavery in the early 19th century.[16] The heavy decline of the white-tailed deer population aided in the pressure for the Chickasaw to adopt chattel slavery, the Chickasaw conceded that they could no longer rely primarily on hunting.[16] It is unclear when the Chickasaw began to think of themselves as potential slave owners of African and African Americans as people they could own as property.[16] The shift toward buying, selling, and exploiting slave labor for material gain accompanied broader, ongoing changes in the ways Chickasaw acquired and valued goods.[16] The Chickasaw excelled in the production of cotton, corn, livestock, and poultry to not only feed their families, but to sell to American families.[16] U.S. Indian agents tracked Chickasaw acquisition of slaves and didn't discourage it, federal officials believed the exploiting of slave labor might enhance Native Americans' understandings of the dynamics of property ownership and commercial gain.[16] The Chickasaw obtained many slaves born in Georgia, Tennessee, or Virginia .[16][19] In 1790 Major John Doughty wrote to Henry Knox, Chickasaws owned a great many horses & some families have Negroes & cattle.[16] Among the Chickasaw who were slaveholders many had European heritage mostly through a white father and a Chickasaw mother.[16] The continued assimilation heavily came through intermarriage as some assimilationists viewed intermarriage as another way to expedite natives' advancement toward civilization, and supported the underlying belief in white superiority.[16] A number of Chickasaw with European heritage rose to prominence because they were related to already politically powerful members of the tribe, not because of racial makeup.[16] Though the Chickasaw did not necessarily prize Euro-American ancestry they did embrace a racial hierarchy that degraded those with African heritage and associated it with enslavement.[16] A further cultural change among the Chickasaw was to have enslaved men work in the fields along with enslaved women, within the Chickasaw tribe agricultural duties belonged to the women.[16] Chickasaw legislators would later condemn sexual relationships between Chickasaw and black people; Chickasaws were punished for publicly taking up with an African American slave with fines, whippings, and ultimately expulsion from the nation.[16] This legislation was also an attempt to keep boundaries between race and citizenship within the tribe.[16] The Chickasaw were also unique among the other civilized tribes as they saw their control over slaves as a particular form of power that could, and should be enacted through violence.[16] The Chickasaw in some cases also practiced the separation of families something not practiced among the other tribes.[16]

Seminole

[edit]The Seminoles took a unique path compared to the other four civilized tribes.[24] The Seminoles targeted and held African American captives, but didn't codify racial slavery.[24] Instead they kept to their traditions to absorb outsiders. Drawing on the chiefly political organization of their ancestors, Seminoles welcomed African Americans, but this increasingly isolated the Seminoles from the rest of the South and even from other Native Americans leading to them being seen as major threats to the plantation economy.[24] The Seminoles were also unique because they absorbed the remaining Yuchis population.[24] African American runaway slaves began to seek refuge in Florida with the Seminoles in the 1790s.[24] One plantation owner in Florida, Jesse Dupont, declared that his slaves began to escape around 1791, when two men ran away to Seminole country he also stated:

An Indian Negro stole a wench and child and since she has been amongst the Indians she has had a Second.[24]

Seminole country quickly became the new locus of black freedom in the region.[24] While the other major Southern Native American nations began to pursue black slavery, political centralization and a new economy, Seminoles drew on culturally conservative elements of native culture and incorporated African Americans as valued members of their communities.[24] Together, they created a new society, one that increasingly isolated them from other southerners.[24] Like other Southern Native Americans, Seminoles accumulated private property, and elites passed down enslaved African Americans and their descendants to relatives. The Seminoles maintained traditional captivity practices longer than other Native Americans, and continued to captive white Americans.[24] The practice of capturing white Americans decreased in the early 19th century with the First Seminole War producing the regions last white captives.[24] Though later to do so than other Native Americans in the south, Seminoles too narrowed their captivity practices.[24] They grew pessimistic about incorporating non-natives into their families as adoptees and almost exclusively targeted people of African descent during their 19th century wars against American expansion.[24] When General Thomas Jesup enumerated the origins of African Americans among the Seminoles to the secretary of war in 1841, he began with "descendants of negroes taken from citizens of Georgia by the Creek confederacy in former wars."[24] When a group of Seminole warriors pledged to join the British in the American Revolution, they stipulated that "Whatever horses or slaves or cattle we take we expect to be our own."[24] Out of the sixty-eight documented captives in the Mikasuki War (1800-1802), 90% were African Americans.[24] The Seminoles repeatedly took up arms to defend their land.[24] They fought in three major conflicts, the Patriot War, the First Seminole War, and the Second Seminole War and were in countless skirmishes with slavescatchers.[24] The Seminoles were at war with the United States far longer than other Southern Native American nations, the Seminoles continued to take black captives, and encouraged African Americans to join them in their fight against American imperialism.[24] The Seminoles continued to destroy and raid plantations.[24] Throughout 1836, Seminole warriors continued to best U.S. troops, but more alarming to white Americans was the relationship between Seminoles and African Americans.[24] They feared that the alliance grew with each passing day, as the Seminoles captured slaves and enticed others to escape.[24] After witnessing the unrest among Creeks forced to emigrate, General Thomas Jesup believed that the Second Seminole War could ignite the entire South in a general uprising, wherein people of color might destroy the region's plantation economy as well as their white oppressors.[24]

The writer William Loren Katz suggests that Native Americans treated their slaves better than European Americans in the Southeast.[25] Federal Agent Hawkins considered the form of slavery the tribes were practicing to be inefficient because the majority didn't practice chattel slavery.[17] Travelers reported enslaved Africans "in as good circumstances as their masters."[25] A white Indian Agent, Douglas Cooper, upset by the Native Americans failure to practice a harsher form of bondage, insisted that Native Americans invite white men to live in their villages and "control matters."[25] One observer in the early 1840s wrote, "The full-blood Indian rarely works himself and but few of them make their slaves work. A slave among wild Indians is almost as free as his owner."[16] Frederick Douglass stated in 1850,

The slave finds more of the milk of human kindness in the bosom of the savage Indian, than in the heart of his Christian master.[26]

Katz thought that slaveholding contributed to divisiveness among tribes of the Southeast and promoted a class hierarchy based on "white blood."[25] Some historians believe that class division was related more to the fact that several of the leadership clans accepted mixed-race chiefs, who were first and foremost on these tribes, and promoting assimilation or accommodation. The Choctaw and Chickasaw nations were also exceptions to the Cherokee, Creek, and Seminole nations; as these tribes abolished slavery immediately after the end of the Civil War the Chickasaw and Choctaw didn't free all of their slaves until 1866.[16]

In 1850 the U.S. Fugitive Slave Law was created and in both ways divided Native Americans in Indian Territory.[16] Runaway slaves in Indian Territory was exceptionally debatable among Native Americans and the U.S. government.[16] Native Americans heavily felt U.S. lawmakers were overstepping their boundaries reaching over federal authority.[16] In the nineteenth century, European Americans began to migrate west from the coastal areas, and encroach on tribal lands, sometimes in violation of existing treaties.[citation needed] Bands along the frontier, in closer contact with traders and settlers, tended to become more assimilated, often led by chiefs who believed they needed to change to accommodate a new society; indeed, some chiefs were mixed-race and were related to elected American officials.[citation needed] Other chiefs had been educated in American schools, and had learned American language and culture.[citation needed] These[who?] were the most likely to become slaveholders and adopt other European practices.[citation needed] Others of their people, often located at more of a distance, held to more traditional practices, and such cultural divisions were the cause of conflict, for instance the Creek Wars (1812–1813) and similar tensions suffered by other Southeast tribes.[citation needed]

With the US increasing pressure for Indian Removal, tensions became higher. Some chiefs believed removal was inevitable and wanted to negotiate the best terms possible to preserve tribal rights, such as the Choctaw Greenwood LeFlore. Others believed they should resist losing ancestral lands.[11] For instance, members of the Cherokee Treaty Party, who believed removal was coming, negotiated cessions of land which the rest of the tribe repudiated.[11] This conflict was carried to Indian Territory, where opponents assassinated some of the signatories of the land cession treaty, for alienating communal land. The tensions among the Native Americans of the Southeast was principally about land and assimilation rather than slavery. Most chiefs agreed that armed resistance was futile.[11] The Five Civilized Tribes took African-American slaves with them to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) when they were removed from the American Southeast by the US Government.[citation needed]

| This is a user sandbox of Chlostall. You can use it for testing or practicing edits. This is not the sandbox where you should draft your assigned article for a dashboard.wikiedu.org course. To find the right sandbox for your assignment, visit your Dashboard course page and follow the Sandbox Draft link for your assigned article in the My Articles section. |

- ^ a b c d e f g Jr, Alton, ed. (2004). "Companion to African American History". pp. 121–139. doi:10.1111/b.9780631230663.2004.00009.x. ISBN 9780631230663.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b c d e f Doran, Michael (1978). "Negro Slaves of the Five Civilized Tribes". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 68 (3). Taylor & Francis, Ltd: 335–350. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1978.tb01198.x. JSTOR 2561972.

- ^ a b c Deloria, Philip J; Salisbury, Neal, eds. (2004). "A Companion to American Indian History". pp. 339–356. doi:10.1111/b.9781405121316.2004.00020.x. ISBN 9781405121316.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b Seybert, Tony (August 4, 2004). "Slavery and Native Americans in British North America and the United States: 1600 to 1865". Archived from the original on 2004-08-04.

- ^ a b Krauthamer, Barbara (2013). Black Slaves, Indian Masters : Slavery, Emancipation, and Citizenship in the Native American South. Chapel Hil: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9781469607108.

- ^ Krauthamer, Barbara (2013). Black Slaves, Indian Masters : Slavery, Emancipation, and Citizenship in the Native American South. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. pp. 17–19. ISBN 9781469607108.

- ^ Bragdon, Kathleen (2010). "Slavery in Indian Country: The Changing Face of Captivity in Early America (review)". Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 42. Harvard University Press: 301–302. doi:10.1162/JINH_r_00232. S2CID 141954638.

- ^ a b Doran, Michael (1978). "Negro Slaves of the Five Civilized Tribes". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 68 (3). Taylor & Francis, Ltd.: 342. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1978.tb01198.x. JSTOR 2561972.

- ^ Krauthamer, Krauthamer (2013). "Chapter Two: Enslaved People, Missionaries, and Slaveholders: Christianity, Colonialism, and Struggles over Slavery". Black Slaves, Indian Masters : Slavery, Emancipation, and Citizenship in the Native American South. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. pp. 46–76. ISBN 9781469607108.

- ^ Dirks, Jerald F. (2006). Muslims in American History: A Forgotten Legacy. Beltsville, MD: Amana Publications. p. 204. ISBN 1590080440. Retrieved March 8, 2017.[better source needed]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Cite error: The named reference

amslavwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

slavbegwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

laubwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Dorothy A. Mays (2008). Women in early America. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851094295. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ^ Brown, Audrey & Knapp, Anthony; et al. (2008). "Work, Marriage, Christianity". African American Heritage and Ethnography. Archived from the original on January 21, 2008. Retrieved March 8, 2017 – via nps.gov.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Content production credits are available for these materials. - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai Krauthamer (2013), "Black Slaves, Indian Masters" [Ch. 1], in Black Slaves, pp. 17–45.[page needed]

- ^ a b Tiya Miles (2008). Ties That Bind: The story of an Afro-Cherokee family in slavery and freedom. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520250024. Retrieved 2009-10-27.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Snyder (2010), "Racial Slavery" [Ch. 7], in Slavery, pp. 182–212.[page needed]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Krauthamer (2013), "Enslaved People, Missionaries, and Slaveholders" [Ch. 2], in Black Slaves, pp. 46-76.[page needed]

- ^ a b c Fay A. Yarbrough (2008). Race and the Cherokee Nation Chap. 3 The 1855 Marriage Law. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 40–72.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Fay A. Yarbrough (2008). Race and the Cherokee Nation Chap. 2 Racial Ideology in Transition. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 39–55.

- ^ William G. McLoughlin (1986). Cherokee Renascence in the New Republic. Princeton University Press.

- ^ William G. McLoughlin (1986). Cherokee Renascence in the New Republic. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691006277. Retrieved 2016-01-09.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Snyder (2010), "Seminoles and African Americans" [Ch. 8], in Slavery, pp. 213–248.[page needed]

- ^ a b c d William Loren Katz (2008). "Africans and Indians: Only in America". William Loren Katz. Archived from the original on 2007-05-29. Retrieved 2008-09-20.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

ismwas invoked but never defined (see the help page).