User:Catjacket/sandbox

Faleme

[edit]Celine Cervera; Louis Champion; Patricia Chique; Eric Huysecom; Anne Mayor (2024). "Djoutoubouya, entre commerce transsaharien et interactions ouest-africains". Falémé: 12 ans de recherches archéologiques an Sénégal oriental, catalogue de l'expositions (Report). Musée Historique de Gorée. pp. 29–33. 13th century unbaked mud brick buildings, rectangles and circles. rare in West africa before 16th cent. - evidence of North African influence -- Mali rise at the same time, likely related -- evidence of working of copper (North African import), maybe gold too since close to Bambouk two ceramic traditions --one up to 12th century, second from 13th - more evidence for a break at the rise of the Mali empire middle of 12th century use of wild animals decreases, domestic animals appear, cotton increases - ties to TS trade

Miriam Truffa Giachet (2024). "Les perles en verre rancontent les échanges en Afrique de l'Ouest et hors de l'Afrique". Falémé: 12 ans de recherches archéologiques an Sénégal oriental, catalogue de l'expositions (Report). Musée Historique de Gorée. pp. 33–35. glass bead found in Mali east of IND dated to middle of 1st mil BCE, made in Egypt/Levant - oldest glass bead found in West Africa beads found 7-13th centuries mostly from middle east and south asia, distributed throughout african networks evidence of Ghana being more tied into the Atlantic economy, while Mali and Senegal are more tied to Venetian beads coming across the Sahara

Eric Huysecom; Nema Guindo; Klena Sanogo; David Glauser (2024). "Le fort d'Orléans, un établissement de la compagnie royale d'Afrique au coeur du Bambouk". Falémé: 12 ans de recherches archéologiques an Sénégal oriental, catalogue de l'expositions (Report). Musée Historique de Gorée. pp. 39–41. 1724 company erects a fort at Farabana upon invitation from king of Bambouk, occupied 24-34, 44-58. protect gold and slave commerce from raids from khassonke and moors, watch the brits. French lived in the village, objects from Europe very rare.

Museum

[edit]Institut Fondamental de l'Afrique Noire. Musée Historique de Gorée Exhibit (August 2024).

- Podor treasure - 1958 a few bracelets were found, podor residents dug up the rest and IFAN managed to buy some

- Tioubalel and Sinthiou Bara show different cermic cultures. SB 6th to 11th, prolly attacked/destroyed by Almoravids

- Lebu left SRV when Koli conquered it, stayed in Jolof for a while, then went to the peninsula - 1795 revolted against Damel Amadi Ngone Ndella Coumba, first serigne dakar Dial Diop. - Serigne Mohamed Diop ruled from before 1852 to death in 1873

- Sosso included upper Senegal - Djolof Mbengue founded Katite village near Yang Yang - Ndiadiane's first capital Tyeng - 1886 Damel Samba Laobe Fall defeated and killed by Alboury Ndiaye at Guille

KAYOR Liste des Souverains 1. Déthiéfou Ndiogou (1 S49) :règne court. 2. Amari Ngoné Sobel (1549-93) Damel-Teigne 3. Massamba Tako (1593-1600) 4. Mamalik Tioro. Teigne et Damel ? 5. Makourédia Kouly (1600-10) 6. Biram Banga Khourédia Kouly (1610 - 40) 1.1)aou Demba Khourédia Kouly (1640 - 47) 8. Madior Fatim Golagne (1647-64) 9. Biram Yasin Boubou (1664-81) 10. Déthiao Maram N galgou (1681-83) 11. Mafaly Faly Guèye (1683-84) 12. Ndiaye Sall (1684) 13. Makhourédia Diodio Diouf (1684-91) Bour Saloum-Dame1 14. Biran Mbenda Thilor (1691), (1691-93) 15. Madiakher (ca 1691) : règne court 16. Déthiélao Bassin Sow (1693-97) 17. Latsoukabé Ngoné Fall (1697-1719) Damel Teigne 18. Maïssa Teindé Wedj (1719-48) Damel Teigne

D'après Tanor Latsoukabé Fall (1974) 19. Maïssa Bigué Ngoné (1748-49), (1756-62) 20. Mawa Mbatio Sambe (1749 - 56) 21. Biram Kodou Ndoumé (1756): règne court 22. Biram Yombé Madjiguèn (1759 - 60) Bourba Dame! 23. Madior Dior Yasin Issa (1763 - 66) 24. Makodou Koumba Diaring (1766 - 77) Damel-Teigne 25. Biram Fatim Penda (1777 - 90), Damel Teigne 26. Amui Ngoné Ndella Koumba (1790 - 1809) Damel-Teigne 27. Biram Fatma Thioub (1809 - 32) Damel-Teigne 28. Maïssa Teindé Dior (1832 - 55) Damel-Teigne 29. Birima Ngoné Latin (1855 - 59) 30. Makodou Koumba Yandé (1859 - 61) 31. Madiodio Deguène Kodou (1861),(1864-68 32. Lat Dior Ngoné Latin (1862-63); (1868-82) Damel-Teigne 33. Samba Yaya Fall (1883) 34. Samba Laobé Fall (1883 - 86)

Liste des Souverains A. Dynastie Wagadu (avant le XVIe siècle) La famille maternelle Wagadu dirigea le Baol pendant plusieurs siècles. D'origine Soninké, elle à des familles serer (arrivées du Fouta-Toro au 11' et 12' siècles), Manding et wolof. Période mai connue. Le fondateur (premier teigne) est Khaya Manga Diata.

B. Dynastie Fall (XVIe au X1Xe siècle) La famille paternelle Fall régna au Cayor et au Baol. La liste des teignes est la suivante:

1. Amary Ngoné Sobel Fall (ca 15204560-70) Damel-Teigne 2. Malamine Thioro (ca 1560-70-ca 1605) Teigne (et Damel?) 3. Lat Ndela Parar (ca 1605-20) 4."Tié Ndéla (ca 1620-65) 5. Mbisan Kura: règne court 6. Ma Kura: règne court 7. Thiandé: règne court 8. Mbaburi Diaw (ca 1669-78) 9. Tié Yasin (ca 1678-91) 10. Makodou Kumba: règne court 11. Tié Tiambal: règne court 12. Latsoukabé (ca 1692-1720). Damel-Teigne 13. Tié Kumba Diaring (1720 - 26) 14. Mali Kumba Diaring (1726 - 35) 15. Makodou K, mba Diaring (1735-1737?) (1756-78) Damel Teigne 16. Maïssa "fende Wed (1737-1748-49). Dame! Teigne 1'7. Tié Yasin isa (1748-49-50), (ca 1751) 18. Maawa (ca 1750-61) (ca 1751-56). Daniel Teigne

19. Amati Ngoné Ndéla Diaring (1778-87) (1790-1809) 20. Biram Fatim Penda (ca 1787-90) Dame! Teigne 21. Tié Yasin Dieng (ca 1809-12) 22. Tié Kumba Fatim Penda: Règne court 23. Amati Dior Borso (ca 1815 - 22) 24. Biram fatiin Thioub (ca 1822-32) Daniel-Teigne 25. Makodu Koumba Guelwar (1832-33); (1855-56-57); (1860) 26. Lat Déguen (ca 1833 - 42) 27. Mali Kumba Diaring (1842); (1845-46); (1848) 28. Massa Teindé Dior (42-ca 1845), (1848-54) Damel-Teigne 29. Tié Yasin Ngoné Déguen (1854-55), (1856-57-60), (1860-71) 30. Tié Yasin Dior Galo gang (1871-73)i (1874-90) 31. Lat Dior Ngone Latir (1873-74 Damel-Teigne 32. Tanor Gogn Dieng (1890-94) Inspiré de V . MARTIN et C. BECKER (1976)

WALO

Liste des souverains . Ndyadyan Ndyay (1186 - 1202). 2. Mbany Waad et ses soeurs (1 202 - 11) 3. Narka Mbody (1211 - 25) 4. Tyaaka Mbar (1225 - 42) 5. Amadu Faaduma (1242 - 51) 6. Tany Yaasin (1251 - 71) 7. Yérim Mbanyik (1271 - 78) 8. Tyukli (1278 - 87) 9. Naatago Tany (1287 - 1304) 10. Fara Yérim (1304 - 16) Mbay Yérim (1316 - 31) 12. Dembaané Yérim (1331 - 36) 13. Ndyak Kumba Sam Dyakekh (1336 - 43) 14. Fara Khet (1343 - 48) 15, Ndyak Kumba-gi-tyi-Ngéloga (1348 - 55) 16. Ndyak Kumba Nan Sangô (1355 - 67) 17. Ndyak Ko Ndyay Mbanyik (1367 - 80) 18. Mbany Naatago (1380 - 81) 19. Mombody Ndyak (1381 - 98) 20. Yérim Mbanyik konêgi (1398 - 1415) 21. Yérim Kodê (1415 - 85) 22. Fara Tako (1485 - 88) 23. Fara Penda Têg Rei (1488 - 96) 24. Tyaaka Daaro Khot (1496 - 1503) 25. Naatago Fara Ndyak (1503 - 08) 26. Naatago Yérim (1508 - 19)

27. Fara Penda Dyeng (1519 - 31) 28. Tany Fara Ndyak (1531 - 42) 29. Fara Koy Dyon ( I 542 - 49) 30. Fara Koy Dyôp (1549 - 52) 31. Fara Penda Langon Dyam (1552 - 56) 32. Fara Ko Ndaama (1556 - 63) 33. Fara Aysa Naalêw (1563 - 65) 34. Naatago Khari Daaro (1565 - 76) 35. Bor Tyaaka (1576 - 1640) 36. Yérim Mbanyik Aram Bakar (1640 - 74) 37. Naatago Aram Bakar (1674 - 1708) 38. Ndyak Aram Bakar (1708 - 33) 39. Yérim Ndate fitubu (1733 - 34) 40. MdS Mbody Kumba Khedy (1734) 41. Yérim Mbanyil Anta Dyop (1735) 42. Yérim Kodé Fara Mbunê (1735 - 36) 43. Ndyak Khuri (1736 - 80) 44. Fara Penda Têg Re] (1780 - 92) 45. Ndyak Kumba Khuri Yay (1792 - 1801) 46. Saayodo Yaasin Mbody (1801 - 06) 47. Kuli Mbaaba (1806 - 12) 48. Amar Faatim Borso (1812 - 21) 49. Yérim Mbanyik têg (1821 - 23) 50. Fara Penda Adam Sa! (1823 - 37) 51. Khêrfi Khari Daaro (1837 - 40) 52. Mt, Mbody Maalik (1840 - 55)

D'après Amadou Wade (publié V. Monteil, 1964)

s

DJOLOF Liste des souveraiits A. Période peu connue ■ . Ndiadiane Ndiaye (Amadou Fatimata Sall). Premier Bourba 2. Sarél•Idiadiane 3. Djiguélane Saré 4. Thioukaly Djiguelane 5. 'Leyti thioukaly 6. Dieulène Mbaye Leyti

B. Période mieux connue 13. Léléfouly Fack: sécession du Kayor 14. Thioukaly Dieulène: règne court 15. Alboury Sarr Ndao: (1570 - 76) 16. Guirane Boury Dieulène (1577 - 1617) 17. Biram Peinda Tabara Mibata (1618 - 48) 18. Biram Mbacouré Peinda Tabara (1649 - 79?) 19. bakar Peinda Kholé (1680 - 1710?) 20. Bakantam Ganne (1711 - 16?) 21. Alboury Diakhéré Lodo (1717 - 18?) 22. Birayamb Madigu.ène Ndao (1719 - 52?) 23. Lat Codou Madjiguène Ndao (1753 - 60?) 24. Bakautam Bouri Gnabou (1761 - 62?) 25. Mbakom Passe (1763 - 76?) 26. Mbaboury (1797 - 1829?) Birayamb Coumba Guèye (1830) 28. Alboury Tam Coumba (1830 - 42) 7. Biram Dieulène 8. Biram Ndiémé Eler 9. Tassé Dagoulène 10. Biram Coura Kane 11. Boucaré Bigué 12. Biram Ndiémé Coumba 29. Baka Codou Bigué Fakontaye (1843 - 44) 30. Birayamb Aram Khourédia (1845 - 46?) 31. Biram Peinda Coumba N'Gouille: règne court 32. Mbagne Paté Coumba Ngouye: règne court 33. Lat Codou Madiguème Peya: règne court 34. Alboury Peya Biram: règne court 35. Bakantam Yago (1850 - 51) 36. Tanor Coura Ngouye (1852 - 53) 37. Birayamb Madjiguène Peya (1853 - 57) 38. Bakantam Khary Dialor (1858 70) 39. Ahmadou Che ikhou (1871 - 75) Mmanay 40. Alboury Ndiagne (1875 - 90) D'après O. Ndiaye Leyti (1966)

SALOUM Liste des souverains Mbégan Ndour (1493 - 1513). Guiranokhap Ndong (1513 - 20 3, Latmingué Dielén Ndiaye 0520 - 4e Samba Lambour Ndiaye (1343 - 47) S. Séni Diémé Dielén Ndiaye (1547 - 50) 6. Lathilor Badiane 1550 - 59) 7. Walbouny Diélén Ndiaye (1559 - 67) 8. Maléotane Diouf (1567 - 1612) 9. Sambaré Diop (1612 - 14) 10. Biram Ndiémé Koumba Ndiaye (1614 - 37) I i. Ndéné Ndiaye Marone Ndao (1637 - 39) 12. MbagneDiémel Ndiaye (1639 - 45) 13. Waldiodio Ndiaye (1645 - 54) 14. Amakodou Ndiaye (1654 - 89) 15. Amafal Fall (1689) règne court 16. Amadiouf Diouf (1690 - 96) 17. Sengane kéwé Ndiaye (1696 - 1790) 18. Lathilor Ndong (1726 - 30) 19. Amui:» Steck Ndiaye (1730 - 32)

20. Biram Khourédia Tiék Ndao (1732 - 34) 21. Néné Ndiaye Bigué Ndao (1734 - 53) Mbagne Diop (1753 - 60) 23. Mbagne Diogop Ndiaye Mbodj (1760 - 67) 24. Sandéné Kodou Bigué Ndao (1767 - 69) 25. Sengane Diogop Mbodj (1769 - 76) 26. Ndéné diogop Mbodj (1776 - 78) 27. Sengane déguène Ndiaye (1778) 28. Sandéné Kodou Fall Ndao(1778 - 87) 29. Biram N. Niakhana Ndiaye (17874 803) 30. Maoumba Diogop Mbodji (1803 - 10) 31. Ndéné Nialdutna Ndiaye (1810 - 17) 32. Biram Khourédia Mbodj Ndiaye (1817- 23) 33. Ndéné Mbarou Ndiaye (1823) 34. Balé Ndoungou Khourédia Ndao (1823 51) 35. Bala Adama Ndiaye (1851 - 54) 36. Socé Bigué Ndiaye (1854 - 55) 37. Koumba Ndama Mbodj (1855 - 59) 38. Samba Laobé Fall (1859 - 64) 39. Fakha Fall (1864 - 71) 40. Niawout Mbodj (1871 - 76) 41. Sadiouka Mbodj (1876 - 79) 42. Guédal Mbodj (1879 - 96) 43. Sémou Djimit Diouf (1896 - 99) 44. Ndiené Ndiénoum Ndao (1899 - 1902) 45. Ndéné Diogop Diouf (1902 - 03) 46. Sémou Ngouye Diouf (1903 - 13) 47. Gori Tioro Diouf (1913 - 19) 48. Mahawa Tioro Diouf (1919 - 35) 49. Fodé Ngouye Diouf (1935 - 69) D'après Abdou Bouri Ba (1976)

Mali

[edit]The history of the Mali Empire begins when the first Mande people entered the Manding region during the period of the Ghana Empire. After its fall, the various tribes established independent chiefdoms. In the 12th century, these were briefly conquered by the Sosso Empire under Soumaoro Kante. He was in turn defeated by a Mande coalition led by Sundiata Keita, who founded the Mali Empire.

The Keita dynasty ruled the Empire for its entire history, with the exception of the third mansa, Sakura, who was a freed slave who took power from one of Sundiata's sons. Upon his death, the Keita line was re-established, and soon led the empire to the peak of its wealth and renown under Mansa Musa. His pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324 became legendary for the vast sums of gold that he gave as gifts and alms, to the point where it created an inflationary crisis in Egypt. Mansa Musa also extended the empire to its greatest territorial extent, re-annexing the city of Gao in the east.

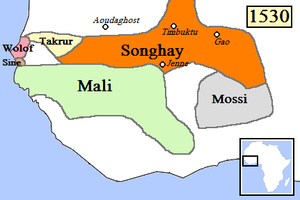

After Mansa Musa's death, the empire slowly weakened. By the mid 15th century, the Sunni dynasty of Gao had established themselves as an independent power. Sunni Ali established the rival Songhai Empire and pushed the Malians out of the Niger bend region and back to their core territories in the south and west. The next century and a half saw Mali repeatedly battle the Songhai and the rising power of the Fula warlords Tenguella and his son Koli Tenguella.

When the Songhai were destroyed by a Moroccan invasion in 1593, Mansa Mahmud IV saw an opportunity to restore Malian pre-eminence in the Niger bend, but a catastrophic defeat outside Jenne in 1599 crippled his prestige. Upon his death, his sons fought over the throne and the empire splintered.

Wagadou

[edit]In the first millennium BC, early cities and towns were founded along the middle Niger River, including at Dia which reached its peak around 600 BC,[1] and Djenne-Djenno, which founded around 250 BC. By the 6th century AD, the lucrative trans-Saharan trade in gold, salt and slaves had begun in earnest, facilitating the rise of West Africa's great empires.

The Manden city-state of Ka-ba (present-day Kangaba) served as the capital and name of the province. From at least the beginning of the 11th century, Mandinka kings ruled Manden from Ka-ba in the name of the Ghanas.[2] The ruler was elected from among the heads of the major clans, and at this time had little real power.[3]

Wagadou's control over Manden ended in the 12th century.[4] The Kangaba province, free of Soninké influence, splintered into twelve kingdoms with their own faama.[5]

In approximately 1140 the Sosso kingdom of Kaniaga, a former vassal of Wagadou, began conquering the lands of its old rulers. In 1203, the Sosso king and sorcerer Soumaoro Kanté came to power and reportedly terrorised much of Manden.[6]

According to Niane's version of the epic, Sundiata Keita was born in the early 13th century. during the rise of Kaniaga. He was the son of Niani's faama, Nare Fa (also known as Maghan Kon Fatta, meaning the handsome prince). Sundiata's mother was Maghan Kon Fatta's second wife, Sogolon Kédjou.[7]

Sundiata, according to the oral traditions, did not walk until he was seven years old.[5] However, once Sundiata eventually gained use of his legs he grew strong and respected, but by that time his father had died. A son from his first wife Sassouma Bérété was crowned instead. As soon as Sassouma's son Dankaran Touman took the throne, he and his mother forced the increasingly popular Sundjata into exile along with his mother and two sisters. Before Dankaran Touman and his mother could enjoy their power, King Soumaoro set his sights on Niani forcing Dankaran to flee to Kissidougou.[7]

After many years in exile, first at the court of Wagadou and then in Mema, a delegation from his home reached Sundjata and begged him to combat the Sosso and free the kingdoms of Manden.

Leading the combined armies of Mema, Wagadou and the Mandinka city-states, Sundiata led a revolt against the Kaniaga Kingdom around 1234.[8] The combined forces of northern and southern Manden defeated the Sosso army at the Battle of Kirina (also known as Krina) in approximately 1235.[9] This victory resulted in the fall of the Kaniaga kingdom and the rise of the Mali Empire. Maghan Sundiata was declared "faama of faamas" and received the title "mansa", which translates as "king". At the age of 18, he gained authority over all the 12 kingdoms in an alliance that became the Mali Empire. He was crowned under the throne name Sundjata Keita becoming the first Mandinka emperor. And so the name Keita became a clan/family and began its reign.[5]

The reign of Mansa Sundiata Keita saw the conquest of several key places in the Mali Empire. He never personally took the field again after Kirina, but his generals continued to expand the frontier, especially in the west where they reached the Gambia River and the marches of Tekrur. This enabled him to rule over a realm larger than even the Ghana Empire in its apex.[9] When the campaigning was done, his empire extended 1,000 miles (1,600 km) east to west with those borders being the bends of the Senegal and Niger rivers.[10] After unifying Manden, he added the Wangara goldfields, making them the southern border. The northern commercial towns of Oualata and Audaghost were also conquered and became part of the new state's northern border. Wagadou and Mema became junior partners in the realm and part of the imperial nucleus. The lands of Bambougou, Jalo (Fouta Djallon), and Kaabu were added into Mali by Fakoli Koroma (known as Nkrumah in Ghana, Kurumah in the Gambia, Colley in Casamance, Senegal),[5] Fran Kamara (Camara) and Tiramakhan Traore (Trawally in the Gambia),[11] respectively.

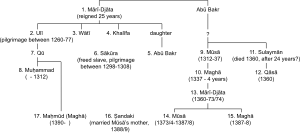

Different oral traditions conflict with each other, as well as with Ibn Khaldun, about the transfer of power following Sunjata's death.[13] There was evidently a power struggle of some kind involving the gbara or great council and donson ton or hunter guilds. In the interregnum following Sunjata's death, the jomba or court slaves may have held power.[14] Some oral traditions agree with Ibn Khaldun in indicating that a son of Sunjata, named Yerelinkon in oral tradition and Wali in Arabic, took power as Sunjata's successor.[15] Ibn Khaldun regarded Wali as one of Mali's greatest rulers.[16] He went on the hajj during the reign of Mamluk sultan Baibars (1260–1277).[a]

Wali was succeeded by his brother Wati, about whom nothing is known,[18][19] and then his brother Khalifa. Khalifa would shoot arrows at his subjects, so he was overthrown and killed.[16] He was replaced by Abu Bakr, a son of Sunjata's daughter. Abu Bakr was the first and only mansa to inherit through the female line, which has been argued to be either a break from or a return to tradition.[20] Then an enslaved court official, Sakura, seized power. Sakura was able to stabilize the political situation in Mali. Under his leadership, Mali conquered new territories and trade with North Africa increased.[21] He went on the hajj during the reign of Mamluk sultan an-Nasir Muhammad (1298–1308) and was killed in Tajura on his way back to Mali.[22] After Sakura's death, power returned to the line of Sunjata, with Wali's son Qu taking the throne.[22] Qu was succeeded by his son Muhammad, who launched two voyages to explore the Atlantic Ocean.[b] After the loss of the first expedition, Muhammad led the second expedition himself. He left Kanku Musa, a grandson of Sunjata's brother Mande Bori, in charge during his absence. Eventually, due to Muhammad's failure to return, Musa was recognized as mansa.[25]

Musa Keita I (Mansa Musa)

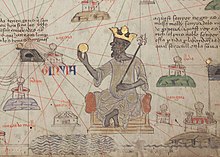

[edit]Kankan Musa, better known as Mansa Musa probably took power in approximately 1312, although an earlier date is possible.[26][27] His reign is considered the golden age of Mali.[28] He was one of the first truly devout Muslims to lead the Mali Empire. He attempted to make Islam the faith of the nobility,[29] but kept to the imperial tradition of not forcing it on the populace. He also made Eid celebrations at the end of Ramadan a national ceremony. He could read and write Arabic and took an interest in the scholarly city of Timbuktu, which he peaceably annexed in 1324. Via one of the royal ladies of his court, Musa transformed Sankore from an informal madrasah into an Islamic university. Islamic studies flourished thereafter.

Mansa Musa Keita's crowning achievement was his famous pilgrimage to Mecca, which started in 1324 and concluded with his return in 1326. Accounts of how many people and how much gold he spent vary. All of them agree that he took a very large group of people; the mansa kept a personal guard of some 500 men,[30] and he gave out so many alms and bought so many things that the value of gold in Egypt and Arabia depreciated for twelve years.[31] When he passed through Cairo, historian al-Maqrizi noted "the members of his entourage proceeded to buy Turkish and Ethiopian slave girls, singing girls and garments, so that the rate of the gold dinar fell by six dirhams."

Mosques were built in Gao and Timbuktu along with impressive palaces also built in Timbuktu. By the time of his death in 1337, Mali had control over Taghazza, a salt-producing area in the north, which further strengthened its treasury.

That same year, after the Mandinka general known as Sagmandir put down yet another rebellion in Gao,[29] Mansa Musa came to Gao and accepted the capitulation of the King of Ghana and his nobles.

Mansa Musa Keita was succeeded by his son, Maghan Keita I, in 1337.[29] Mansa Maghan Keita I spent wastefully and was the first lacklustre emperor since Khalifa Keita. But the Mali Empire built by his predecessors was too strong for even his misrule and it passed intact to Musa's brother, Souleyman Keita in 1341.

Souleyman Keita

[edit]Mansa Souleyman Keita (or Suleiman) took steep measures to put Mali back into financial shape, thereby developing a reputation for miserliness.[29] It is during his reign that Fula raids on Takrur began. There was also a palace conspiracy to overthrow him hatched by the Qasa (the Manding term meaning Queen) Kassi and several army commanders.[29] Mansa Souleyman's generals successfully fought off the military incursions, and the senior wife Kassi behind the plot was imprisoned.

The mansa also made a successful hajj, kept up correspondence with Morocco and Egypt and built an earthen platform at Kangaba called the Camanbolon where he held court with provincial governors and deposited the holy books he brought back from Hedjaz.

The only major setback to his reign was the loss of Mali's Dyolof province in Senegal. The Wolof populations of the area united into their own state known as the Jolof Empire in the 1350s. Still, when Ibn Battuta arrived at Mali in July 1352, he found a thriving civilisation on par with virtually anything in the Muslim or Christian world. Mansa Souleyman Keita died in 1360 and was succeeded by his son, Camba Keita.

Mari Djata Keita II

[edit]After a mere nine months of rule, Mansa Camba Keita was deposed by one of Maghan Keita I's three sons. Konkodougou Kamissa Keita, named for the province he once governed,[5] was crowned as Mansa Mari Djata Keita II in 1360. He ruled oppressively and nearly bankrupted Mali with his lavish spending. Mansa Mari Djata Keita II became seriously ill in 1372,[29] and power moved into the hands of his ministers until his death in 1374.

Musa Keita II

[edit]The reign of Mari Djata Keita II was ruinous and left the empire in bad financial shape, but the empire itself passed intact to the dead emperor's brother. Mansa Fadima Musa Keita, or Mansa Musa Keita II, began the process of reversing his brother's excesses.[29] He did not, however, hold the power of previous mansas because of the influence of his kankoro-sigui.

Kankoro-sigui Mari Djata, who had no relation to the Keita clan, essentially ran the empire in Musa Keita II's stead. Ibn Khaldun recorded that in 776 A.H or 1374/1375 AD he interviewed a Sijilmasan scholar named Muhammad b. Wasul who had lived in Gao and had been employed in its judiciary. The latter told Ibn Khaldun about devastating struggle over Gao between Mali imperial forces against Berber Tuareg forces from Takedda.[32] The text of Ibn Khaldun says "Gao, at this time is devastated".[32] It seems quite possible that an exodus of the inhabitants took place at this juncture and the importance of the city was not revived until the rise of the Songhai empire.[32]

The Songhai settlement effectively shook off Mali's authority in 1375. Still, by the time of Mansa Musa Keita II's death in 1387, Mali was financially solvent and in control of all of its previous conquests short of Gao and Dyolof. Forty years after the reign of Mansa Musa Keita I, the Mali Empire still controlled some 1,100,000 square kilometres (420,000 sq mi) of land throughout Western Africa.[33]

Maghan Keita II

[edit]The last son of Maghan Keita I, Tenin Maghan Keita (also known as Kita Tenin Maghan Keita for the province he once governed) was crowned Mansa Maghan Keita II in 1387.[5] Little is known of him except that he only reigned two years. He was deposed in 1389, marking the end of the Faga Laye Keita mansas.

Sandaki Keita

[edit]Mansa Sandaki Keita, a descendant of kankoro-sigui Mari Djata Keita, deposed Maghan Keita II, becoming the first person without any Keita dynastic relation to officially rule Mali.[29] Sandaki Keita should not however be taken to be this person's name but a title. Sandaki likely means High Counsellor or Supreme Counsellor, from san or sanon (meaning "high") and adegue (meaning counsellor).[34] He only reigned a year before a descendant of Mansa Gao Keita removed him.[5]

Mahmud Keita, possibly a grandchild or great-grandchild of Mansa Gao Keita, was crowned Mansa Maghan Keita III in 1390. During his reign, the Mossi emperor Bonga of Yatenga raided into Mali and plundered Macina.[29] Emperor Bonga did not appear to hold the area, and it stayed within the Mali Empire after Maghan Keita III's death in 1400.

Rise of Songhai

[edit]In the early 15th century, Mali was still powerful enough to conquer and settle new areas. One of these was Dioma, an area south of Niani populated by Fula Wassoulounké.[5] Two noble brothers from Niani, of unknown lineage, went to Dioma with an army and drove out the Fula Wassoulounké. The oldest brother, Sérébandjougou Keita, was crowned Mansa Foamed or Mansa Musa Keita III. His reign saw the first in a string of many great losses to Mali. In 1433–1434, the Mali Empire lost control of Timbuktu to the Tuareg, led by Akil Ag-Amalwal.[35][36] Three years later, Oualata also fell into their hands.[29]

Following Musa Keita III's death, his brother Gbèré Keita became emperor in the mid-15th century.[5] Gbèré Keita was crowned Mansa Ouali Keita II and ruled during the period of Mali's contact with Portugal. In the 1450s, Portugal began sending raiding parties along the Gambian coast.[37] The Gambia was still firmly in Mali's control, and these raiding expeditions met with disastrous fates before Portugal's Diogo Gomes began formal relations with Mali via its remaining Wolof subjects.[38] Alvise Cadamosto, a Venetian explorer, recorded that the Mali Empire was the most powerful entity on the coast in 1454.[38]

Despite their power in the west, Mali was losing the battle for supremacy in the north and northeast. The new Songhai Empire conquered Mema,[29] one of Mali's oldest possessions, in 1465. It then seized Timbuktu from the Tuareg in 1468 under Sunni Ali Ber.[29]

In 1477, the Yatenga emperor Nasséré made yet another Mossi raid into Macina, this time conquering it and the old province of BaGhana (Wagadou).[39]

Mansa Mahmud Keita II came to the throne in 1481 during Mali's downward spiral. It is unknown from whom he descended; however, another emperor, Mansa Maghan Keita III, is sometimes cited as Mansa Mahmud Keita I. Still, throne names do not usually indicate blood relations. Mansa Mahmud Keita II's rule was characterised by more losses to Mali's old possessions and increased contact between Mali and Portuguese explorers along the coast. In 1481, Fula raids against Mali's Tekrur provinces began.

The growing trade in Mali's western provinces with Portugal witnessed the exchange of envoys between the two nations. Mansa Mahmud Keita II received the Portuguese envoys Pêro d'Évora and Gonçalo Enes in 1487.[5] The mansa lost control of Jalo during this period.[40] Meanwhile, Songhai seized the salt mines of Taghazza in 1493. That same year, Mahmud II sent another envoy to the Portuguese proposing alliance against the Fula. The Portuguese decided to stay out of the conflict and the talks concluded by 1495 without an alliance.[40]

Songhai forces under the command of Askia Muhammad I defeated the Mali general Fati Quali Keita in 1502 and seized the province of Diafunu.[29] In 1514, the Denianke dynasty was established in Tekrour and it was not long before the new kingdom of Great Fulo was warring against Mali's remaining provinces.[41]

In 1534, Mahmud III, the grandson of Mahmud II, received another Portuguese envoy to the Mali court by the name of Pero Fernandes.[42] This envoy from the Portuguese coastal port of Elmina arrived in response to the growing trade along the coast and Mali's now urgent request for military assistance against Songhai.[43] Still, no help came from the envoy and further possessions of Mali were lost one by one. The date of Mahmud's death and identity of his immediate successor are not recorded, and there is a gap of 65 years before another mansa's identity is recorded.[44]

In 1544 or 1545,[c] a Songhai force led by kanfari Dawud, who later succeeded his brother Askia Ishaq as ruler of the Songhai Empire, sacked the capital of Mali and purportedly used the royal palace as a latrine.[45] However, the Songhai do not maintain their hold on the Malian capital.[46]

Mali's fortunes seem to have improved in the second half of the 16th century. Around 1550, Mali attacked Bighu in an effort to regain access to its gold.[47] Songhai authority over Bendugu and Kala declined by 1571, and Mali may have been able to reassert some authority over them.[46] The breakup of the Wolof Empire allowed Mali to reassert authority over some of its former subjects on the north bank of the Gambia, such as Wuli, by 1576.[48]

Collapse

[edit]The swan song of the Mali Empire came in 1599, under the reign of Mansa Mahmud IV. The Songhai Empire had fallen to the Saadi Sultanate of Morocco eight years earlier, and Mahmud sought to take advantage of their defeat by trying to capture Jenne.[49] Mahmud sought support from several other rulers, including the governor of Kala, Bukar. Bukar professed his support, but believing Mahmud's situation to be hopeless, secretly went over to the Moroccans. The Malian and Moroccan armies fought at Jenne on 26 April, the last day of Ramadan, and the Moroccans were victorious thanks to their firearms and Bukar's support, but Mahmud was able to escape.[50]

It would be the Mandinka themselves that would cause the final destruction of the empire. Around 1610, Mahmud Keita IV died. Oral tradition states that he had three sons who fought over Manden's remains. No single Keita ever ruled Manden after Mahmud Keita IV's death, resulting in the end of the Mali Empire.[51]

Notes

[edit]- ^ His hajj was during the reign of Baibars, which was from 1260 to 1277.[17]

- ^ There is some ambiguity over the identity of the mansa responsible for the voyages. The voyage is often incorrectly attributed to a Mansa Abu Bakr II, but no such mansa ever reigned.[23] The account of the voyage does not mention the mansa by name, only indicating that it was Musa's immediate predecessor. According to Ibn Khaldun, Musa's immediate predecessor was Muhammad.[24]

- ^ 952 AH

References

[edit]- ^ Arazi, Noemie. "Tracing History in Dia, in the Inland Niger Delta of Mali -Archaeology, Oral Traditions and Written Sources" (PDF). University College London. Institute of Archaeology.

- ^ Heusch, Luc de: "The Symbolic Mechanisms of Sacred Kingship: Rediscovering Frazer". The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 1997.

- ^ Cissoko 1983, pp. 57.

- ^ Lange, Dierk (1996), "The Almoravid expansion and the downfall of Ghana", Der Islam 73 (2): 313–351

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Niane 1975

- ^ "African Empires to CE 1500". Fsmitha.com. 2007-01-17. Retrieved 2009-09-16.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

sundiatawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Mali | World Civilization". courses.lumenlearning.com. Retrieved 2020-05-10.

- ^ a b Blanchard 2001, p. 1117.

- ^ VMFA. "Mali: Geography and History". Vmfa.state.va.us. Archived from the original on 2001-10-30. Retrieved 2009-09-16.

- ^ Mike Blondino. "LEAD: International: The History of Guinea-Bissau". Leadinternational.com. Archived from the original on 1 November 2010. Retrieved 2009-09-16.

- ^ Levtzion 1963.

- ^ Gomez 2018, p. 93.

- ^ Gomez 2018, pp. 93, 95.

- ^ Gomez 2018, p. 96.

- ^ a b Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 333.

- ^ Levtzion 1963, p. 344.

- ^ Gomez 2018, p. 97.

- ^ Niane 1959.

- ^ Gomez 2018, p. 94.

- ^ Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 334.

- ^ a b Levtzion 1963, p. 345.

- ^ Fauvelle 2018, p. 165.

- ^ Levtzion 1963, p. 346.

- ^ Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 269.

- ^ Levtzion 1963, pp. 349–350.

- ^ Bell 1972, pp. 224–225.

- ^ Levtzion 1963, pp. 347.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Stride, G. T., & C. Ifeka: "Peoples and Empires of West Africa: West Africa in History 1000–1800". Nelson, 1971.

- ^ "African". Sarasota.k12.fl.us. Archived from the original on 31 May 2008. Retrieved 2009-09-16.

- ^ "Kingdom of Mali". Bu.edu. Archived from the original on 31 August 2009. Retrieved 2009-09-16.

- ^ a b c Saad, Elias N. (14 July 1983). Social History of Timbuktu: The Role of Muslim Scholars and Notables 1400-1900 (Cambridge History of Science Cambridge Studies in Islamic Civilization ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 29–30. ISBN 0521246032.

- ^ Imperato & Imperato 2008, p. 203.

- ^ Cooley 1966, p. 66.

- ^ Hunwick 1999, pp. 12, 30.

- ^ Levtzion 1973, p. 81.

- ^ Thornton, John K.: Warfare in Atlantic Africa, 1500–1800. Routledge, 1999.

- ^ a b Cosmovisions.com [dead link]

- ^ "Mossi (1250–1575 AD) – DBA 2.0 Variant Army List". Fanaticus.org. 2006-08-21. Archived from the original on 2 August 2009. Retrieved 2009-09-16.

- ^ a b "Etext.org". Archived from the original on 11 July 2006.

- ^ Kelly Mass (December 9, 2023). African History A Closer Look at Colonies, Countries, and Wars. Efalon Acies. ISBN 9791222482699. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

Denianke dynasty was established at Tekrour in 1514, leading to war with Mali's surviving regions by Great Fulo's new kingdom.

- ^ "The history of Africa – Peul and Toucouleur". Retrieved 2009-09-16.

- ^ "Africa and Slavery 1500–1800 by Sanderson Beck". San.beck.org. Retrieved 2009-09-16.

- ^ Person 1981, p. 643.

- ^ Gomez 2018, p. 331.

- ^ a b Person 1981, p. 618.

- ^ Wilks 1982, p. 470.

- ^ Person 1981, p. 621.

- ^ Ly-Tall 1984, p. 184.

- ^ al-Sadi, translated in Hunwick 1999, pp. 234–235

- ^ Jansen 1996.

Primary sources

[edit]- al-Bakri, Kitāb al-masālik wa-ʼl-mamālik [The Book of Routes and Realms], translated in Levtzion & Hopkins 2000

- al-Idrisi (1154), Nuzhat al-mushtāq fī ikhtirāq al-āfāq نزهة المشتاق في اختراق الآفاق [The Pleasure of Him Who Longs to Cross the Horizons], translated in Levtzion & Hopkins 2000

- Ibn Khaldun, Kitāb al-ʻIbar wa-dīwān al-mubtadaʼ wa-l-khabar fī ayyām al-ʻarab wa-ʼl-ʻajam wa-ʼl-barbar [The Book of Examples and the Register of Subject and Predicate on the Days of the Arabs, the Persians and the Berbers]. Translated in Levtzion & Hopkins 2000.

- al-Sadi, Taʾrīkh al-Sūdān, translated in Hunwick 1999

Other sources

[edit]- Bell, Nawal Morcos (1972). "The Age of Mansa Musa of Mali: Problems in Succession and Chronology". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 5 (2): 221–234. doi:10.2307/217515. ISSN 0361-7882. JSTOR 217515.

- Blanchard, Ian (2001). Mining, Metallurgy and Minting in the Middle Ages Vol. 3. Continuing Afro-European Supremacy, 1250–1450. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 3-515-08704-4.

- Cissoko, Sekene Mody (1983). "Formations sociales et État en Afrique précoloniale : Approche historique". Présence Africaine. COLLOQUE SUR « LA PROBLÉMATIQUE DE L'ÉTAT EN AFRIQUE NOIRE » (127/128): 50–71. doi:10.3917/presa.127.0050. JSTOR 24350899. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- Conrad, David C. (2004). Sunjata: a West African epic of the Mande peoples. Indianapolis: Hackett. ISBN 0-87220-697-1.

- Cooley, William Desborough (1966) [1841]. The Negroland of the Arabs Examined and Explained. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-1799-7.

- Delafosse, Maurice (1912). Haut-Sénégal Niger (in French). Vol. I. Le Pays, les Peuples, les Langues. Paris: Maisonneuve & Larose.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Delafosse, Maurice (1912). Haut-Sénégal Niger (in French). Vol. II. L'Histoire. Paris: Maisonneuve & Larose.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Delafosse, Maurice (1912). Haut-Sénégal Niger (in French). Vol. III. Les civilisations. Paris: Maisonneuve & Larose.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Fauvelle, François-Xavier (2018) [2013]. The Golden Rhinoceros: Histories of the African Middle Ages. Troy Tice (trans.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-18126-4.

- Gomez, Michael A. (2018). African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400888160.

- Goodwin, A. J. H. (1957). "The Medieval Empire of Ghana". South African Archaeological Bulletin. 12 (47): 108–112. doi:10.2307/3886971. JSTOR 3886971.

- Hunwick, John O. (1999). Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Saʻdi's Taʼrīkh al-Sūdān down to 1613, and other contemporary documents. Islamic history and civilization : studies and texts. Leiden; Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-11207-0.

- Imperato, Pascal James; Imperato, Gavin H. (2008). Historical Dictionary of Mali. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5603-5.

- Jansen, Jan (1996). "The Representation of Status in Mande: Did the Mali Empire Still Exist in the Nineteenth Century?". History in Africa. 23: 87–109. doi:10.2307/3171935. hdl:1887/2775. JSTOR 3171935. S2CID 53133772.

- Levtzion, N. (1963). "The thirteenth- and fourteenth-century kings of Mali". Journal of African History. 4 (3): 341–353. doi:10.1017/S002185370000428X. JSTOR 180027. S2CID 162413528.

- Levtzion, Nehemia (1973). Ancient Ghana and Mali. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-8419-0431-6.

- Levtzion, Nehemia; Hopkins, John F.P., eds. (2000). Corpus of Early Arabic Sources for West Africa. New York: Marcus Weiner Press. ISBN 1-55876-241-8. First published in 1981 by Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-22422-5

- Ly-Tall, M. (1984). "The decline of the Mali Empire". In Niane, D. T. (ed.). Africa from the Twelfth to the Sixteenth Century. General history of Africa. Vol. 4. Paris: UNESCO. pp. 172–186. ISBN 92-3-101-710-1.

- Niane, Djibril Tamsir (1959). "Recherches sur l'Empire du Mali au Moyen Age". Recherches Africaines (in French). Archived from the original on 2007-05-19.

- Niane, D. T. (1975). Recherches sur l'Empire du Mali au Moyen Âge. Paris: Présence Africaine.

- Person, Yves (1981). "Nyaani Mansa Mamudu et la fin de l 'empire du Mali". Publications de la Société française d'histoire des outre-mers: 613–653.

- Wilks, Ivor (1982). "Wangara, Akan and Portuguese in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries. II. The Struggle for Trade". The Journal of African History. 23 (4): 463–472. doi:10.1017/S0021853700021307. JSTOR 182036. S2CID 163064591.