User:A.D.Hope/subpage

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2011) |

| Angevin Civil War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| English royalists (Angevin Empire) |

English rebels Kingdom of France Kingdom of Scotland Duchy of Brittany County of Flanders County of Boulogne | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

King Henry II Richard de Luci Ranulf de Glanvill |

Eleanor of Aquitaine (wife of Henry II) (POW) Henry the Young King (son of Henry II) Richard, Count of Poitou (son of Henry II) Geoffrey II, Duke of Brittany (son of Henry II) Robert de Beaumont(POW) Hugh Bigod David, Earl of Huntingdon William de Ferrers (POW) Hugh de Kevelioc (POW) William the Lion (POW) Louis VII of France Philip I of Flanders Matthew of Boulogne † | ||||||||

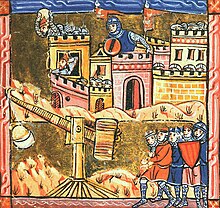

The Angevin Civil War was a successful rebellion against King Henry II of England by three of his sons, his wife Eleanor of Aquitaine, and their supporters. The primary cause of the conflict was Henry's unwillingness to grant his lands to his children, particularly his eldest son Henry 'the Young King', who despite being crowned as junior King of England in 1163 had no actual control over the kingdom.

conflict ended with Henry's deposition and the division of his territories between his children, a process Henry had already been planning for.

Background

[edit]King Henry II ruled England, Normandy, and Anjou, while his wife Queen Eleanor ruled the vast territory of Aquitaine. In 1173 Henry had four legitimate sons (from oldest to youngest): Henry, called the "Young King", Richard (later called "the Lionheart"), Geoffrey, and John "Lackland", all of whom stood to inherit some or all of these possessions. Henry also had an illegitimate son named Geoffrey, born probably before the eldest of the legitimate children.[1]

Henry "the Young King" was 18 years old in 1173 and praised for his good looks and charm. He had been married for a long time to the daughter of Louis VII, the King of France and Eleanor's ex-husband. Henry the Young King kept a large and glamorous retinue but was constrained by his lack of resources: "he had many knights but he had no means to give rewards and gifts to the knights".[2] The young Henry was therefore anxious to take control of some of his ancestral inheritances to rule in his own right.

The immediate practical cause of the rebellion was Henry II's decision to bequeath three castles, which were within the realm of the Young King's inheritance, to his youngest son, John, as part of the arrangements for John's marriage to the daughter of the Count of Maurienne. At this, Henry the Young King was encouraged to rebel by many aristocrats who saw potential profit and gain in a power transition. His mother Eleanor had been feuding with her husband, and she joined the cause as did many others upset by Henry's possible involvement in the murder of Archbishop Thomas Becket in 1170, which had left Henry alienated throughout Christendom.

In March 1173 Henry the Young King withdrew to the court of his father-in-law, Louis, in France and was soon followed by his brothers Richard and Geoffrey. Eleanor tried to join them but was stopped by Henry II on the way and held in captivity. The Young King and his French mentor created a wide alliance against Henry II by promising land and revenues in England and Anjou to the Counts of Flanders, Boulogne, and Blois; William the Lion, King of the Scots, would have Northumberland. In effect, the Young King would seize his inheritance by breaking it apart.

- ^ Fryde et al. 1996, p. 36

- ^ Bartlett 2000, p. 55