Typhoon Alice (1979)

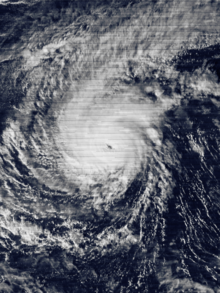

Alice at its peak intensity on January 7, 1979 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | December 31, 1978 |

| Dissipated | January 15, 1979 |

| Very strong typhoon | |

| 10-minute sustained (JMA) | |

| Highest winds | 175 km/h (110 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 930 hPa (mbar); 27.46 inHg |

| Category 3-equivalent typhoon | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/JTWC) | |

| Highest winds | 205 km/h (125 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 930 hPa (mbar); 27.46 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | None |

| Damage | ≤ $500,000 (1979 USD) |

| Areas affected | Marshall Islands, Guam |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1979 Pacific typhoon season | |

Typhoon Alice was an unusual and strong West Pacific tropical cyclone that caused extensive damage in the Marshall Islands in January 1979. The first tropical cyclone and the first typhoon of the 1979 Pacific typhoon season, Alice formed on December 31, 1978, from a tropical disturbance at both an atypically low latitude near the equator and during a time of year climatologically unfavorable for tropical cyclogenesis. The system strengthened as it tracked northwest, reaching tropical storm strength on January 1, 1979. Alice then began to move erratically through the Marshall Islands, causing heavy rainfall and gusty winds that destroyed crops throughout the archipelago. Significant damage occurred in Majuro and Enewetak Atoll, where gusts of 80 mph (130 km/h) were reported and one person was injured. Nuclear cleanup operations on Enewetak in the wake of postwar nuclear tests there were disrupted, with repair of cleanup facilities lasting several months. The damage toll was estimated at between US$50,000–$500,000.

After January 6, Alice strengthened into a typhoon and took a westward course, strengthening to its peak intensity with winds of 125 mph (205 km/h) two days later. A weakening trend began thereafter as the storm tracked south of Guam on January 10, prompting thousands to evacuate to shelters though ultimately causing minor damage. After passing the island Typhoon Alice reintensified to a secondary peak intensity before strong wind shear induced rapid weakening, resulting in the storm's dissipation on January 15.

Meteorological history

[edit]

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

The origins of Alice were traced back to a tropical disturbance over the Gilbert Islands on December 27, 1978, during a climatologically unfavorable time for tropical cyclone formation.[1] The disturbance was segmented into two components directly north and south of the equator.[2] Initially, the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) believed that the disturbance's placement near the equator meant further storm development was unlikely.[1] However, the system progressively organized and was classified as a tropical depression by the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) by 12:00 UTC on December 31.[3] The JTWC followed suit in the upgrade twelve hours later, and soon after declared a tropical cyclone formation alert at 03:00 UTC on January 1, 1979. Tracking towards the northwest, atmospheric conditions became more favorable for intensification farther from the equator. The tropical depression became sufficiently organized to be named Tropical Storm Alice by the JTWC at 18:00 UTC that day.[1] Over the next several days, Alice meandered through the Marshall Islands without much change in strength,[1][4] steered by a transient shortwave trough.[1]

The trough's influence soon abated, allowing a nearby ridge of high pressure to restrengthen and induce a westerly bearing to Alice's motion that would continue for five days.[1] Alice strengthened into a typhoon on January 6 and continued to intensify thereafter, reaching a peak intensity on January 8 with maximum sustained winds of 125 mph (205 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 930 mbar (hPa; 27.46 inHg).[4] Concurrently, the typhoon accelerated to a forward speed of 16 mph (26 km/h) and began to weaken. An area of wind shear southeast of Guam, described by the JTWC as a "frontal shear-line", slowed Alice's movement on January 9. A region of cooler and drier air north of this region was entrained also into the storm, causing Alice to lose some organization and weaken further. Two days later, a second trough over eastern Asia resulted in Alice curving north.[1] During this trek, the typhoon restrengthened and reached a secondary peak intensity with winds of 115 mph (185 km/h) on January 11, with satellite imagery indicating robust outflow.[1][4] However, this second peak was short-lived as Alice's circulation began to vertically decouple in the face of strong wind shear, exacerbated by Alice's low-level circulation moving directly into the westerly wind flow aloft.[1] The typhoon degenerated into a tropical storm on January 13 and weakened further into a tropical depression 18 hours later; these remnants dissipated by January 15.[1][3]

Preparations, impact, and aftermath

[edit]

In its earlier stages of development, Alice passed near several of the Marshall Islands.[1] At the time, nuclear waste cleanup operations were ongoing at Enewetak Atoll following the United States' postwar nuclear tests there. On January 4, storm preparations were ordered for military assets on the atoll, beaching boats, evacuating cargo ships, and securing buildings. Most personnel stationed at Lojwa Camp were evacuated to Enewetak Camp.[5] The center of the storm tracked within 50 mi (80 km) northeast of Kwajalein Atoll on the morning January 4 before passing within 30 mi (48 km) south of Enewetak two days later. Rough surf at Kwajalein damaged breakwaters and piers.[6] Sustained winds there reached 36 mph (58 km/h) with gusts to 51 mph (82 km/h). Significant shoreline damage occurred along the lagoon-facing shores of the Kwajalein Missile Range, compounded by Alice's nearly stationary movement.[7]

Gusts of 80 mph (130 km/h) were measured at Enewetak where "considerable" damage was observed;[6] the tropical storm battered the atoll for over six hours.[8] The damage was worst at Enewetak Camp and minor at Japtan and Lojwa Camps on the atoll. A water tower was blown down and sheet metal was torn from the roofs and walls of buildings. Some buildings collapsed due to the winds.[5] Large rocks were washed onto the runway at Enewetak Auxiliary Airfield.[6] Storm surge inundated the Mid-Pacific Research Laboratory grounds under 5 ft (1.5 m) of water and washed out roads. A few boats, including a Landing Craft Utility and LCM-8, sustained minor damage.[5] The storm cut off all power, forcing nuclear waste cleanup crews on the atoll to use emergency generators.[8] "Extensive" damage was reported in Majuro, the capital of the Marshall Islands, and crops were destroyed throughout the archipelago.[9] One person suffered minor injuries at Enewetak,[10] and the damage toll was estimated at between US$50,000–$500,000.[6] Population density and species richness of the sea snail genus Conus decreased as a result of the typhoon.[11] Alice's presence also disrupted U.S. Coast Guard search and rescue operations for a missing sailboat with two onboard, preventing search planes from departing out of Kwajalein Atoll.[12] U.S. President Jimmy Carter declared the Marshall Islands a disaster area,[1] with federal disaster assistance activated for eight atolls.[13] Initial recovery efforts following Alice at Enewetak lasted three weeks and cost over $264,000, while longer-term repair and replacement of nuclear cleanup facilities lasted several months.[5]

With Typhoon Alice expected to track near Guam, the island's civil defense force was placed on alert.[9] All schools were closed aside from 20 used as shelters,[14] housing thousands of evacuees.[15] The United States Navy evacuated a submarine tender and submarines from the island.[9] The United States Air Force was evacuated 14 B-52 bombers and five tanker planes from Andersen Air Force Base to Kadena Air Force Base in Okinawa.[9][15] Alice ultimately moved within 90 mi (140 km) south of Guam on January 10, causing minor damage as strong winds and large waves affected the island.[6]

See also

[edit]- Other systems named Alice

- List of tropical cyclones near the Equator

- Typhoon Hester (1952) – a similar strong typhoon that formed in December and persisted into January.

- Typhoon Mary (1977) – an erratic typhoon that formed in December 1977 before striking the Philippines in January 1978

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Shewchuk, John D. (1979). "Typhoon Alice (01)" (PDF). 1979 Annual Tropical Cyclone Report (Report). Annual Tropical Cyclone Report. Guam, Northern Mariana Islands: Joint Typhoon Warning Center. pp. 16–17. Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ^ Ogura, Yoshi; Chin, Hung-Neng (August 1987). "A Case Study of Cross-Equatorial Twin Vortices Over the Pacific in Northern Winter Using FGGE Data" (PDF). Journal of the Meteorological Society of Japan. 65 (4). Tokyo, Japan: J-STAGE: 669–674. doi:10.2151/jmsj1965.65.4_669. Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ^ a b RSMC Best Track Data: 1970–1979 (Report). Tokyo, Japan: Japan Meteorological Agency. October 21, 1992. Archived from the original (TXT) on May 7, 2021. Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ^ a b c "1978 Typhoon ALICE (1978361N02180)". International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship. Asheville, North Carolina: University of North Carolina-Asheville. Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Soil Cleanup Operations". The Radiological Cleanup of Enewetak Atoll (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Defense Nuclear Agency. 1981. pp. 348–352. Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "January 1979" (PDF). Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena. 21 (1). Asheville, North Carolina: National Centers for Environmental Information: 7. January 1979. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 21, 2019. Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ^ Lee, Michael T. (December 1985). US Department of the Army Permit Application for Discharge of Fill Material for the Kwajalein Atoll Causeway Project (Environmental Impact Statement). United States Army Corps of Engineers. p. IV-6. Retrieved July 20, 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b "International briefs". The Calgary Herald. Calgary, Alberta, Canada. United Press International. January 6, 1979. p. A4. Retrieved July 20, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d "Guam Braces for Typhoon Alice". The Honolulu Advertiser. Honolulu, Hawaii. January 9, 1979. p. C-1. Retrieved July 20, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Typhoon Grows, Takes Aim at Guam". The Tampa Tribune. No. 7. Tampa, Florida. United Press International. January 8, 1979. p. 2-A. Retrieved July 20, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Kohn, Alan J. (December 1980). "Populations of Tropical Intertidal Gastropods Before and After a Typhoon" (PDF). Micronesica. 16 (2). Mangilao, Guam: University of Guam. Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ^ "Storm Alice Hampers Search for Pair". Hawaii Tribune-Herald. No. 3. Hilo, Hawaii. United Press International. January 3, 1979. p. 10. Retrieved July 20, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Vulnerability and Adaptation (V&A) Assessment for the Water Sector in Majuro, Republic of the Marshall Islands (PDF) (Report). Apia, Samoa: Pacific Adaptation to Climate Change Programme. June 2014. p. 15. ISSN 2312-8224. Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ^ "Guam Typhoon Alert Cancelled". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Vol. 68, no. 9. Honolulu, Hawaii. Gannett News Service. January 9, 1979. p. A-8. Retrieved July 20, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Guam hammered by wind". The Boston Globe. Vol. 215, no. 10. Boston, Massachusetts. Reuters. January 10, 1979. p. 4. Retrieved July 20, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.