Kachina

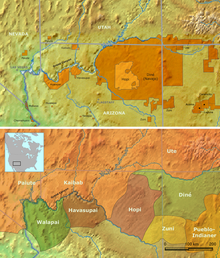

A kachina (/kəˈtʃiːnə/; also katchina, katcina, or katsina; Hopi: katsina [kaˈtsʲina], plural katsinim [kaˈtsʲinim]) is a spirit being in the religious beliefs of the Pueblo people, Native American cultures located in the south-western part of the United States. In the Pueblo cultures, kachina rites are practiced by the Hopi, Hopi-Tewa and Zuni peoples and certain Keresan tribes, as well as in most Pueblo tribes in New Mexico.

The kachina concept has three different aspects: the supernatural being, the kachina dancers, and kachina dolls (small dolls carved in the likeness of the kachina, that are given only to those who are, or will be responsible for the respectful care and well-being of the doll, such as a mother, wife, or sister).[2]

Overview

[edit]Kachinas are spirits or personifications of things in the real world. These spirits are believed to visit the Hopi villages during the first half of the year. The local pantheon of kachinas varies from pueblo community to community. A kachina can represent anything in the natural world or cosmos, from a revered ancestor to an element, a location, a quality, a natural phenomenon, or a concept; there may be kachinas for the sun, stars, thunderstorms, wind, corn, insects, as well as many other concepts.

Kachinas are understood as having human-like relationships: families such as parents and siblings, as well as marrying and having children. Although not worshipped,[3] each is viewed as a powerful being who, if given veneration and respect, can use his particular power for human good, bringing rainfall, healing, fertility, or protection, for example. The central theme of kachina beliefs and practices as explained by Wright (2008) is "the presence of life in all objects that fill the universe. Everything has an essence or a life force, and humans must interact with these or fail to survive."[4]

Commercialization

[edit]Beginning around 1900, there was a great deal of interest in the Kachina figurines, especially among tourists, and the dolls became sought-after collectibles. For this reason, many Hopi began making the figurines commercially to make a living.[5]

Hopi kachinas

[edit]In many ways the Kachina rites are the most important ceremonial observances in the Hopi religious calendar. Within Hopi religion, the kachinas are said to live on the San Francisco Peaks near Flagstaff, Arizona. To the Hopis, kachinas are supernatural beings who visit the villages to help the Hopis with everyday activities and act as a link between gods and mortals.[6]

According to Susanne and Jake Page, the katsinam are "the spirits of all things in the universe, of rocks, stars, animals, plants, and ancestors who have lived good lives."[citation needed]

The first ceremony of the year, the Powamu, occurs in February and is associated with the bean planting, the growing season, and coming of age. The last katsina ceremony, Niman, occurs in July and is associated with the harvest, after which the katsinam return to their home in the San Francisco Peaks.

Hopi kachina dolls, tihü, are ceremonial objects with religious meaning. Hopi carvers alter these, removing their religious meaning, to meet the demand for decorative commercial objects sought by non-Hopi.[7]

Wuya

[edit]The most important Hopi kachinas are known as wuya. In Hopi, the term wuya often refers to the spiritual beings themselves (said to be connected with the Fifth World, Taalawsohu), the dolls, or the people who dress as kachinas for ceremonial dances. These are all understood to embody all aspects of the same belief system. Some of the wuyas include:

- Ahöla

- Ahöl Maana

- Aholi

- Ahul

- Ahulani

- Akush

- Alosaka

- Angak

- Angwushahai-i

- Angwusnasomtaka

- Eototo

- Hahay-i Wuhti

- He-e-e

- Horo or Yohozro Wuhti

- Hu

- Huruing Wuhti

- Kalavi

- Kaletaka

- Ketowa Visena

- Kötsav

- Kököle

- Kokopelli

- Kokosori

- Kokyang Wuhti

- Koshari or Koyaala

- Kwasai Taka

- Lemowa

- Masau'u

- Mastop

- Maswik

- Mong

- Muyingwa

- Nakiatsop

- Nataska

- Ongtsomo

- Pahlikmana or Polik-mana

- Patsava Hú

- Patung

- Pöqangwhoya

- Pohaha or Pahana

- Saviki

- Shalako Taka

- Shalako Mana

- Söhönasomtaka

- Soyal

- Tanik'tsina

- Tawa

- Tiwenu

- Toho

- Tokoch

- Tsaveyo

- Tsa'kwayna

- Tsimon Maana

- Tsitot

- Tsiwap

- Tsowilawu

- Tukwinong

- Tukwinong Mana

- Tumas

- Tumuala

- Tungwup

- Ursisimu

- We-u-u

- Wiharu

- Wukoqala

- Wupa-ala

- Wupamo

- Wuyak-kuyta

Zuni kachinas

[edit]Religious ceremonies are central to the Zuni agrarian society. They revolve around the winter and summer solstices, incorporate the importance of weather, especially rain, and ensure successful crops. According to Tanner, "Father Sky and Mother Earth are venerated, as are the welcome kachinas who bring many blessings."[8]

The Zuni believe that the kachinas live in the Lake of the Dead, a mythical lake which is reached through Listening Spring Lake. This is located at the junction of the Zuni River and the Little Colorado River. Although some archaeological investigations have taken place, they have not been able to clarify which tribe, Zuni or Hopi, developed the Kachina Cult first. Both Zuni and Hopi kachinas are different from each other but have certain similarities and features. In addition, both Zuni and Hopi kachinas are highly featured and detailed, while the kachinas of the Rio Grande Pueblos look primitive in feature.[clarification needed] The Hopis have built their cult into a more elaborate rite, and seem to have a greater sense of drama and artistry than the Zunis. On the other hand, the latter have developed a more sizable folklore concerning their kachinas.[9]

According to Clara Lee Tanner, "...kachina involves three basic concepts: first, a supernatural being; second, the masked dancer (and the Zuni is a kachina when he wears the mask), and third the carved, painted, and dressed doll." The list of Zuni kachinas includes:[8]

- A'Hute

- Ainawua

- Ainshekoko

- Anahoho

- A'thlanna

- Atoshle Otshi

- Awan Pekwin

- Awan Pithlashiwanni

- Awan Tatchu

- Awek Suwa Hanona

- Bitsitsi

- Chakwaina

- Chakwaina Okya

- Chathlashi

- Chilili

- Eshotsi

- Hainawi

- Hehea

- Hehe'a

- Hemokatsiki

- Hemushikiwe

- Hetsululu

- Hilili Kohana

- Hututu

- Ishan Atsan Atshi

- Itetsona

- Itsepasha

- Kakali

- Kalutsi

- Kanatshu

- Kanilona

- Kiaklo

- Kianakwe

- Kianakwe Mosona

- Kokokshi

- Kokothlanna

- Kokwele

- Komokatsiki

- Kothlamana

- Koyemshi

- Kwamumu

- Kwamumu Okya

- Kwelele

- Lapilawe

- Mahedinasha

- Mitotasha

- Mitsinapa

- Mókwala

- Mukikwe

- Mukikw' Okya

- Muluktaka

- Muyapona

- Nahalisho

- Nahalish Awan Mosona

- Nahalish Okya

- Nalashi

- Na'le

- Na'le Okya

- Na'le Otshi

- Natashku

- Natshimomo

- Nawisho

- Neneka

- Nepaiyatemu

- Ohapa

- Oky'enawe (Girls)

- Ololowishkia

- Owiwi

- Paiyatamu

- Pakoko

- Pakok'Okya

- Pasikiapa

- Pautiwa

- Posuki

- Potsikish

- Saiyapa

- Saiyatasha

- Saiyathlia

- Salimopia Itapanahnan'ona

- Salimopia Kohan'ona

- Salimopia Shelow'ona

- Salimopia Shikan'ona

- Salimopia Thlian'ona

- Salimopia Thluptsin'ono

- Sate'tshi E'lashokti

- Shalako (6)

- Shalako Anuthlona

- Shi-tsukia

- Shulawitsi

- Shulawitsi An Tatchu

- Shulawitsi Kohanna

- Shumaikoli

- Siwolo

- Suyuki

- Temtemshi

- Thlelashoktipona

- Thlewekwe

- Thlewekwe Okya

- Tomtsinapa

- Tsathlashi

- Upikaiapona

- Upo'yona

- Wahaha

- Wakashi

- Wamuwe

- Wilatsukwe

- Wilatsukw' Okya

- Wo'latana

- Yamuhakto

- Yeibichai

Ceremonial dancers

[edit]Many Pueblo Indians, particularly the Hopi and Zuni, have ceremonies in which masked men, called kachinas, play an important role. Masked members of the tribe dress up as kachinas for religious ceremonies that take place many times throughout the year. These ceremonies are social occasions for the village, where friends and relatives are able to come from neighboring towns to see the dance and partake in the feasts that are always prepared. When a Hopi man places a mask upon his head and wears the appropriate costume and body paint, his personal identity is lost and the spirit of the kachina he is supposed to represent takes its place. Besides the male kachinas are many female kachinas called kachin-manas, but women never take the part of male or female kachinas.[10]

The most widely publicised of Hopi kachina rites is the "Snake Dance", an annual event during which the performers danced while handling live snakes.[11]

Clowns

[edit]

Clown personages play dual roles. Their prominent role is to amuse the audience during the extended periods of the outdoor celebrations and Kachina Dances where they perform as jesters or circus clowns. Barry Pritzker stated, regarding the role of clowns in Hopi dances,

The clowns play an important role-embodying wrong social behavior, they are soon put in their place by the katsinam for all to see. The presence of clowns in the morality play makes people more receptive to the messages of proper social convention and encourages a crucial human trait: a keen sense of humor.[7]: 29

The clown's more subtle and sacred role is in the Hopis' ritual performances. The sacred functions of the clowns are relatively private, if not held secret by the Hopi, and as a result have received less public exposure. When observing the preparations taking place in a Kiva of a number of Pai'yakyamu clowns getting ready for their ceremonial performance, Alexander Stephen was told, "We Koyala [Koshari] are the fathers of all Kachina."[12]

The Hopi have four groups of clowns, some of which are sacred. Adding to the difficulty in identifying and classifying these groups, there are a number of kachinas whose actions are identified as clown antics. Barton Wright's Clowns of the Hopi identifies, classifies, and illustrates the extensive array of clown personages.[13]

Kachina dolls

[edit]Kachina dolls are small brightly painted wooden "dolls" which are miniature representations of the masked impersonators. These figurines are given to children not as toys, but as objects to be treasured and studied so that the young Hopis may become familiar with the appearance of the kachinas as part of their religious training. During Kachina ceremonies, each child receives their own doll. The dolls are then taken home and hung up on the walls or from the rafters of the house, so that they can be constantly seen by the children. The purpose of this is to help the children learn to know what the different kachinas look like. It is said that the Hopi recognize over 200 kachinas and many more were invented in the last half of the nineteenth century. Among the Hopi, kachina dolls are traditionally carved by the maternal uncles and given to uninitiated girls at the Bean Dance (Spring Bean Planting Ceremony) and Home Dance Ceremony in the summer. These dolls are very difficult to classify not only because the Hopis have a vague idea about their appearance and function, but also because these ideas differ from mesa to mesa and pueblo to pueblo.[14]

Origins

[edit]There are two different accounts in Hopi beliefs for the origins of kachinas. According to one version, the kachinas were good-natured spirit-beings who came with the Hopis from the underworld.[15] The kachinas wandered with the Hopis over the world until they arrived at Casa Grande, where both the Hopis and the kachinas settled. With their powerful ceremonies, the kachinas were of much help and comfort, for example bringing rain for the crops. However, all of the kachinas were killed when the Hopis were attacked and the kachinas' souls returned to the underworld. Since the sacred paraphernalia of the kachinas were left behind, the Hopis began impersonating the kachinas, wearing their masks and costumes, and imitating their ceremonies in order to bring rain, good crops, and life's happiness.

Another account says that the Hopis came to take the kachinas for granted, losing all respect and reverence for them, so the kachinas returned to the underworld. However, before they left, the kachinas taught some of their ceremonies to a few faithful young men and showed them how to make the masks and costumes. When the other Hopi realized their mistake, they remorsefully turned to the kachinas' human substitutes, and the ceremonies have continued since then.[16]

See also

[edit]Notes

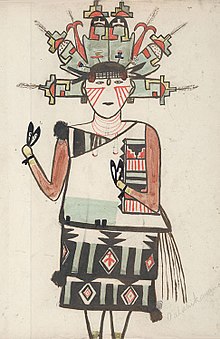

[edit]- ^ Sacred Women in North American Rock Art, August 20, 2011. Image is from the Bureau of American Ethnology 21st Annual Report.

- ^ Colton, Harold Sellers (1959). Hopi Kachina Dolls: with a Key to their Identification (rev. ed.). Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-0-8263-0180-2.

- ^ Wright (1965), p. 4.

- ^ Wright (2008), p. 4.

- ^ "Appendix 3", Hopi Katsina Songs, UNP - Nebraska, pp. 383–405, doi:10.2307/j.ctt1d98bd5.16, retrieved 2022-10-30

- ^ Dockstader, Frederick J. (1954). The Kachina and the White Man: a study of the influences of White culture on the Hopi kachina cult. Bloomsfield Hills, Mich.: Cransbrook Institute of Science. p. 9.

- ^ a b Pritzker, Barry (2011). The Hopi. New York: Chelsea House. pp. 26–33. ISBN 9781604137989.

- ^ a b Wright, Barton (1988). History and Background of Zuni Culture, in Patterns and Sources of Zuni Kachinas. Hamsen Publishing Company. pp. 37–39, 155. ISBN 9780960132249.

- ^ Dockstader, Frederick J. (1954). The Kachina and the White Man: a study of the influences of White culture on the Hopi kachina cult. Bloomfield Hills, Mich.: Cransbrook Institute of Science. pp. 28–29.

- ^ Colton, Harold Sellers (1959). Hopi Kachina Dolls: with a Key to their Identification (rev. ed.). Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. pp. 2–4. ISBN 978-0-8263-0180-2.

- ^ "Hopi people". Encyclopedia Britannica. 28 March 2008.

- ^ Stephen, Alexander. Hopi Journal of Alexander M. Stephen. Edited by E. C. Parsons. Columbia University Contributions to Anthropology, 23, 2 volumes; 1936. P411-12.

- ^ Wright, Barton. Clowns of the Hopi. Northland Publishing; ISBN 0-87358-572-0. 1994.

- ^ Colton, Harold Sellers (1959). Hopi Kachina Dolls: with a Key to their Identification. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-0-8263-0180-2.

- ^ The underworld is a concept common to all the Pueblo Indians. It is a place where the spirits or shades live: the newly born come from there and the dead return there.

- ^ Dockstader, Frederick J. (1954). The Kachina and the White Man: a study of the influences of White culture on the Hopi kachina cult. Bloomfield Hills, Mich.: Cranbrook Institute of Science. pp. 10–11.

References

[edit]- Anderson, Frank G. (1955). The Pueblo Kachina Cult: A Historical Reconstruction. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology, 11, 404–419.

- Anderson, Frank G. (1956). Early documentary material on the Pueblo kachina cult. Anthropological Quarterly, 29, 31–44.

- Anderson, Frank G. (1960). Inter-tribal relations in the Pueblo kachina cult. In Fifth International Congress of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences, selected papers (pp. 377–383).

- Dockstader, Frederick J. The Kachina & The White Man: A Study of The Influence of White Culture on The Hopi Kachina Cult, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan: Cranbook Institute of Science, 1954.

- Dozier, Edward P. (1970). The Pueblo Indians of North America. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

- Glenn, Edna "Kachinas," in Hopi Nation: Essays on Indigenous Art, Culture, History, and Law, 2008.

- Kennard, Edward A. & Edwin Earle. "Hopi Kachinas." New York: Museum of The American Indian, Hye Foundation, 1971.

- Schaafsma, Polly. (1972). Rock Art in New Mexico. Santa Fe: State Planning Office..

- Pecina, Ron and Pecina, Bob. Hopi Kachinas: History, Legends, and Art. Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 2013. ISBN 978-0-7643-4429-9; pp. 124–138

- Schaafsma, Polly (Ed.). (1994). Kachinas in the pueblo world. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

- Schaafsma, Polly; & Schaafsma, Curtis F. (1974). Evidence for the origins of the Pueblo katchina cult as suggested by Southwestern rock art. American Antiquity, 39 (4), 535-545.

- Schlegel, Alice, "Hopi Social Structure as Related to Tihu Symbolism," in Hopi Nation: Essays on Indigenous Art, Culture, History, and Law, 2008.

- Sekaquaptewa, Helen. "Me & Mine: The Life Story of Helen Sekaquaptewa." Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press, 1969.

- Stephen, Alexander M. "Hopi Journal." New York: Columbia University Press, 1936.

- Stephen, Alexander. Hopi Journal of Alexander M. Stephen. Edited by E. C. Parsons. Columbia University Contributions to Anthropology, 23, 2 volumes; 1936.

- Stewart, Tyrone. Dockstader, Frederick. Wright, Barton. "The Year of The Hopi: Paintings & Photographs by Joseph Mora, 1904-06." New York, Rizzoli International Publications, 1979.

- Talayesua, Don C. "Sun Chief: The Autobiography of a Hopi Indian." New Haven, Connecticut: Institute of Human Relations/Yale University Press, 1942.

- Titiev, Mischa. "Old Oraibi: A Study of The Hopi Indians of the Third Mesa." Cambridge, Massachusetts: Peabody Museum, 1944.

- Wright, Barton. Clowns of the Hopi. Northland Publishing; ISBN 0-87358-572-0. 1994

- Wright, Barton (1965). Roat, Evelyn (ed.). This is a Hopi Kachina. USA: Museum of Northern Arizona.

- Wright, Barton. "Hopi Kachinas: The Complete Guide to Collecting Kachina Dolls." Flagstaff, Arizona: Northland Press, 1977.

- Wright, Barton, "Hopi Kachinas: A Life Force," in Hopi Nation: Essays on Indigenous Art, Culture, History, and Law, 2008.

- Wright, Barton (2008), "Hopi Kachinas: A Life Force", Hopi Nation: Essays on Indigenous Art, Culture, History, and Law, USA: Univ. of Nebraska Digital Commons, 6.3, retrieved 2010-06-22

External links

[edit]- Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology: Rainmakers From the Gods

- Native paths: American Indian art from the collection of Charles and Valerie Diker, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on kachinas