Trousers

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2023) |

Man wearing a pair of trousers | |

| Material | |

|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Various |

Trousers (British English), slacks, or pants (American, Canadian and Australian English) are an item of clothing worn from the waist to anywhere between the knees and the ankles, covering both legs separately (rather than with cloth extending across both legs as in robes, skirts, dresses and kilts). In some parts of the United Kingdom, the word pants is ambiguous: it can mean trousers rather than underpants.[1] Shorts are similar to trousers, but with legs that come down only to around the area of the knee, higher or lower depending on the style of the garment. To distinguish them from shorts, trousers may be called "long trousers" in certain contexts such as school uniform, where tailored shorts may be called "short trousers" in the UK.

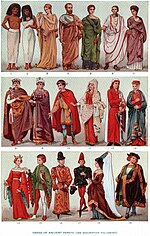

The oldest known trousers, dating to the period between the thirteenth and the tenth centuries BC, were found at the Yanghai cemetery in Turpan, Xinjiang (Tocharia), in present-day western China.[2][3] Made of wool, the trousers had straight legs and wide crotches and were likely made for horseback riding.[4][5] A pair of trouser-like leggings dating back to 3350 and 3105 BC were found in the Austria–Italy border worn by Ötzi. In most of Europe, trousers have been worn since ancient times and throughout the Medieval period, becoming the most common form of lower-body clothing for adult males in the modern world. Breeches were worn instead of trousers in early modern Europe by some men in higher classes of society. Distinctive formal trousers are traditionally worn with formal and semi-formal day attire. Since the mid-twentieth century, trousers have increasingly been worn by women as well.

Jeans, made of denim, are a form of trousers for casual wear widely worn all over the world by people of all genders. Shorts are often preferred in hot weather or for some sports and also often by children and adolescents. Trousers are worn on the hips or waist and are often held up by buttons, elastic, a belt or suspenders (braces). Unless elastic, and especially for men, trousers usually provide a zippered or buttoned fly. Jeans usually feature side and rear pockets with pocket openings placed slightly below the waist band. It is also possible for trousers to provide cargo pockets further down the legs.

Maintenance of fit is more challenging for trousers than for some other garments. Leg-length can be adjusted with a hem, which helps to retain fit during the adolescent and early adulthood growth years. Tailoring adjustment of girth to accommodate weight gain or weight loss is relatively limited, and otherwise serviceable trousers may need to be replaced after a significant change in body composition. Higher-quality trousers often have extra fabric included in the centre-back seam allowance, so the waist can be let out further.

Terminology

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2012) |

In Scotland, a type of tartan trousers traditionally worn by Highlanders as an alternative to the Great Plaid and its predecessors is called trews or in the original Gaelic triubhas. This is the source of the English word trousers. Trews are still sometimes worn instead of the kilt at ceilidhs, weddings etc. Trousers are also known as breeks in Scots, the cognate of breeches. The item of clothing worn under trousers is called pants. The standard English form trousers is also used, but it is sometimes pronounced in a manner approximately represented by [ˈtruːzɨrz], as Scots did not completely undergo the Great Vowel Shift, and thus retains the vowel sound of the Gaelic triubhas, from which the word originates.[6]

In North America, Australia and South Africa,[7] pants is the general category term, whereas trousers (sometimes slacks in Australia and North America) often refers more specifically to tailored garments with a waistband, belt-loops, and a fly-front. In these dialects, elastic-waist knitted garments would be called pants, but not trousers (or slacks).[citation needed]

North Americans call undergarments underwear, underpants, undies, or panties (the last are women's garments specifically) to distinguish them from other pants that are worn on the outside. The term drawers normally refers to undergarments, but in some dialects, may be found as a synonym for breeches, that is, trousers. In these dialects, the term underdrawers is used for undergarments. Many North Americans refer to their underpants by their type, such as boxers or briefs.[citation needed]

In Australia, men's underwear also has various informal terms including under-dacks, undies, dacks or jocks. In New Zealand, men's underwear is known informally as undies or dacks.[citation needed]

In India, underwear is also referred to as innerwear.[citation needed]

The words trouser (or pant) instead of trousers (or pants) is sometimes used in the tailoring and fashion industries as a generic term, for instance when discussing styles, such as "a flared trouser", rather than as a specific item. The words trousers and pants are pluralia tantum, nouns that generally only appear in plural form—much like the words scissors and tongs, and as such pair of trousers is the usual correct form. However, the singular form is used in some compound words, such as trouser-leg, trouser-press and trouser-bottoms.[8]

Jeans are trousers typically made from denim or dungaree cloth. In North America skin-tight leggings are commonly referred to as tights.[citation needed]

Types

[edit]There are several different main types of pants and trousers, such as dress pants, jeans, khakis, chinos, leggings, overalls, and sweatpants. They can also be classified by fit, fabric, and other features. There is apparently no universal, overarching classification.[citation needed]

History

[edit]

Prehistory

[edit]

There is some evidence, from figurative art, of trousers being worn in the Upper Paleolithic, as seen on the figurines found at the Siberian sites of Mal'ta and Buret'.[9] Fabrics and technology for their construction are fragile and disintegrate easily, so often are not among artefacts discovered in archaeological sites. The oldest known trousers were found at the Yanghai cemetery, extracted from mummies in Turpan, Xinjiang, western China, belonging to the people of the Tarim Basin;[3] dated to the period between the thirteenth and the tenth century BC and made of wool, the trousers had straight legs and wide crotches, and were likely made for horseback riding.[4][5]

Antiquity

[edit]

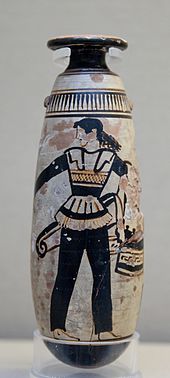

Trousers enter recorded history in the sixth century BC, on the rock carvings and artworks of Persepolis,[10][self-published source?] and with the appearance of horse-riding Eurasian nomads in Greek ethnography. At this time, Iranian peoples such as Scythians, Sarmatians, Sogdians and Bactrians among others, along with Armenians and Eastern and Central Asian peoples such as the Xiongnu/Hunnu, are known to have worn trousers.[11][12] Trousers are believed to have been worn by people of any gender among these early users.[13]

The ancient Greeks used the term ἀναξυρίδες (anaxyrides) for the trousers worn by Eastern nations[14] and σαράβαρα (sarabara) for the loose trousers worn by the Scythians.[15] However, they did not wear trousers since they thought them ridiculous,[16][17] using the word θύλακοι (thulakoi), pl. of θύλακος (thulakos) 'sack', as a slang term for the loose trousers of Persians and other Middle Easterners.[18]

Republican Rome viewed the draped clothing of Greek and Minoan (Cretan) culture as an emblem of civilization and disdained trousers as the mark of barbarians.[19] As the Roman Empire expanded beyond the Mediterranean basin, however, the greater warmth provided by trousers led to their adoption.[20] Two types of trousers eventually saw widespread use in Rome: the feminalia, which fit snugly and usually fell to knee length or mid-calf length,[21] and the braccae, loose-fitting trousers that were closed at the ankles.[22] Both garments were adopted originally from the Celts of Europe, although later familiarity with the Persian Near East and the Germanic peoples increased acceptance. Feminalia and braccae both began use as military garments, spreading to civilian dress later, and were eventually made in a variety of materials, including leather, wool, cotton and silk.[23]

Medieval Europe

[edit]Trousers of various designs were worn throughout the Middle Ages in Europe, especially by men. Loose-fitting trousers were worn in Byzantium under long tunics,[24] and were worn by many tribes, such as the Germanic tribes that migrated to the Western Roman Empire in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages, as evidenced by both artistic sources and such relics as the fourth-century costumes recovered from the Thorsberg peat bog (see illustration).[25] Trousers in this period, generally called braies, varied in length and were often closed at the cuff or even had attached foot coverings, although open-legged pants were also seen.[26]

By the eighth century there is evidence of the wearing in Europe of two layers of trousers, especially among upper-class males.[27] The under layer is today referred to by costume historians as drawers, although that usage did not emerge until the late sixteenth century. Over the drawers were worn trousers of wool or linen, which in the tenth century began to be referred to as breeches in many places. Tightness of fit and length of leg varied by period, class, and geography. (Open legged trousers can be seen on the Norman soldiers of the Bayeux Tapestry.)[28]

Although Charlemagne (742–814) is recorded to have habitually worn trousers, donning the Byzantine tunic only for ceremonial occasions,[29][30] the influence of the Roman past and the example of Byzantium led to the increasing use of long tunics by men, hiding most of the trousers from view and eventually rendering them an undergarment for many. As undergarments, these trousers became briefer or longer as the length of the various medieval outer garments changed, and were met by, and usually attached to, another garment variously called hose or stockings.[citation needed]

In the fourteenth century it became common among the men of the noble and knightly classes to connect the hose directly to their pourpoints[31] (the padded under jacket worn with armoured breastplates that would later evolve into the doublet) rather than to their drawers. In the fifteenth century, rising hemlines led to ever briefer drawers[32] until they were dispensed with altogether by the most fashionable elites who joined their skin-tight hose back into trousers.[33] These trousers, which we would today call tights but which were still called hose or sometimes joined hose at the time, emerged late in the fifteenth century and were conspicuous by their open crotch which was covered by an independently fastening front panel, the codpiece. The exposure of the hose to the waist was consistent with fifteenth-century trends, which also brought the pourpoint/doublet and the shirt, previously undergarments, into view,[34] but the most revealing of these fashions were only ever adopted at court and not by the general population.[citation needed]

Men's clothes in Hungary in the fifteenth century consisted of a shirt and trousers as underwear, and a dolman worn over them, as well as a short fur-lined or sheepskin coat. Hungarians generally wore simple trousers, only their colour being unusual; the dolman covered the greater part of the trousers.[35]

Europe before the 20th century

[edit]Around the turn of the sixteenth century it became conventional to separate hose into two pieces, one from the waist to the crotch which fastened around the top of the legs, called trunk hose, and the other running beneath it to the foot. The trunk hose soon reached down the thigh to fasten below the knee and were now usually called "breeches" to distinguish them from the lower-leg coverings still called hose or, sometimes stockings. By the end of the sixteenth century, the codpiece had also been incorporated into breeches which featured a fly or fall front opening.[citation needed]

As a modernization measure, Tsar Peter the Great of Russia issued a decree in 1701 commanding every Russian man, other than clergy and peasant farmers, to wear trousers.[36]

Western dress shall be worn by all the boyars, members of our councils and of our court...gentry of Moscow, secretaries...provincial gentry, gosti,[3] government officials, streltsy,[4] members of the guilds purveying for our household, citizens of Moscow of all ranks, and residents of provincial cities...excepting the clergy and peasant tillers of the soil. The upper dress shall be of French or Saxon cut, and the lower dress...--waistcoat, trousers, boots, shoes, and hats--shall be of the German type

During the French Revolution of 1789 and following, many male citizens of France adopted a working-class costume including ankle-length trousers, or pantaloons (named from a Commedia dell'Arte character named Pantalone)[37] in place of the aristocratic knee-breeches (culottes). (Compare sans-culottes.) The new garment of the revolutionaries differed from that of the ancien regime upper classes in three ways:[citation needed]

- it was loose where the style for breeches had most recently been form-fitting

- it was ankle length where breeches had generally been knee-length for more than two centuries

- they were open at the bottom while breeches were fastened

Pantaloons became fashionable in early nineteenth-century England and the Regency era. The style was introduced by Beau Brummell (1778–1840)[38][39][40] and by mid-century had supplanted breeches as fashionable street-wear.[41] At this point, even knee-length pants adopted the open bottoms of trousers (see shorts) and were worn by young boys, for sports, and in tropical climates. Breeches proper have survived into the twenty-first century as court dress, and also in baggy mid-calf (or three-quarter length) versions known as plus-fours or knickers worn for active sports and by young schoolboys. Types of breeches are also still worn today by baseball and American football players, and by equestrians.[citation needed]

Sailors may[original research?] have played a role in the worldwide dissemination of trousers as a fashion. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, sailors wore baggy trousers known as galligaskins. Sailors also pioneered the wearing of jeans – trousers made of denim.[42] These became more popular in the late nineteenth century in the American West because of their ruggedness and durability.[citation needed]

Starting around the mid-nineteenth century, Wigan pit-brow women scandalized Victorian society by wearing trousers for their work at the local coal mines. They wore skirts over their trousers and rolled them up to their waists to keep them out of the way. Although pit-brow lasses worked above ground at the pit-head, their task of sorting and shovelling coal involved hard manual labour, so wearing the usual long skirts of the time would have greatly hindered their movements.[citation needed]

Medieval Korea

[edit]The Korean word for trousers, baji (originally pajibaji) first appears in recorded history around the turn of the fifteenth century, but pants may have been in use by Korean society for some time. From at least this time pants were worn by both sexes in Korea. Men wore trousers either as outer garments or beneath skirts, while it was unusual for adult women to wear their pants (termed sokgot) without a covering skirt. As in Europe, a wide variety of styles came to define regions, time periods and age and gender groups, from the unlined gouei to the padded sombaji.[43]

Women wearing trousers

[edit]See also: the Laws section below.

In Western society, it was Eastern culture that inspired French designer Paul Poiret (1879–1944) to be one of the first to design pants for women. In 1913, Poiret created loose-fitting, wide-leg trousers for women called harem pants, which were based on the costumes of the popular ballet Sheherazade. Written by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov in 1888, Sheherazade was based on a collection of legends from the Middle East called 1001 Arabian Nights.[44]

In the early twentieth century, women air pilots and other working women often wore trousers. Frequent photographs from the 1930s of actresses Marlene Dietrich and Katharine Hepburn in trousers helped make trousers acceptable for women. During World War II, women employed in factories or doing other "men's work" on war service wore trousers when the job demanded it. In the post-war era, trousers became acceptable casual wear for gardening, the beach, and other leisure pursuits. In Britain during World War II the rationing of clothing prompted women to wear their husbands' civilian clothes, including trousers, to work while the men were serving in the armed forces. This was partly because they were seen as practical for work, but also so that women could keep their clothing allowance for other uses. As this practice of wearing trousers became more widespread and as the men's clothing wore out, replacements were needed. By the summer of 1944, it was reported that sales of women's trousers were five times more than the previous year.[45]

In 1919, Luisa Capetillo challenged mainstream society by becoming the first woman in Puerto Rico to wear trousers in public. Capetillo was sent to jail for what was considered to be a crime, but the charges were later dropped.[citation needed]

In the 1960s, André Courrèges introduced long trousers for women as a fashion item, leading to the era of the pantsuit and designer jeans and the gradual erosion of social prohibitions against girls and women wearing trousers in schools, the workplace and in fine restaurants.[citation needed]

In 1969, Rep. Charlotte Reid (R-Ill.) became the first woman to wear trousers in the US Congress.[46]

Pat Nixon was the first American First Lady to wear trousers in public.[47]

In 1989, California state senator Rebecca Morgan became the first woman to wear trousers in a US state senate.[48]

Hillary Clinton was the first woman to wear trousers in an official American First Lady portrait.[49]

Women were not allowed to wear trousers on the US Senate floor until 1993.[50][51] In 1993, Senators Barbara Mikulski and Carol Moseley Braun wore trousers onto the floor in defiance of the rule, and female support staff followed soon after; the rule was amended later that year by Senate Sergeant-at-Arms Martha Pope to allow women to wear trousers on the floor so long as they also wore a jacket.[50][51]

In Malawi women were not legally allowed to wear trousers under President Kamuzu Banda's rule until 1994.[52] This law was introduced in 1965.[53]

Since 2004 the International Skating Union has allowed women to wear trousers instead of skirts in ice-skating competitions.[54]

In 2009, journalist Lubna Hussein was fined the equivalent of $200 when a court found her guilty of violating Sudan's decency laws by wearing trousers.[55]

In 2012 the Royal Canadian Mounted Police began to allow women to wear trousers and boots with all their formal uniforms.[56]

In 2012 and 2013, some Mormon women participated in "Wear Pants to Church Day", in which they wore trousers to church instead of the customary dresses to encourage gender equality within the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.[57][58] More than one thousand women participated in 2012.[58]

In 2013, Turkey's parliament ended a ban on women lawmakers wearing trousers in its assembly.[59]

Also in 2013, an old bylaw requiring women in Paris, France to ask permission from city authorities before "dressing as men", including wearing trousers (with exceptions for those "holding a bicycle handlebar or the reins of a horse") was declared officially revoked by France's Women's Rights Minister, Najat Vallaud-Belkacem.[60] The bylaw was originally intended to prevent women from wearing the pantalons fashionable with Parisian rebels in the French Revolution.[60]

In 2014, an Indian family court in Mumbai ruled that a husband objecting to his wife wearing a kurta and jeans and forcing her to wear a sari amounts to cruelty inflicted by the husband and can be a ground to seek divorce.[61] The wife was thus granted a divorce on the ground of cruelty as defined under section 27(1)(d) of the Special Marriage Act, 1954.[61]

Until 2016 some female crew members on British Airways were required to wear British Airways' standard "ambassador" uniform, which has not traditionally included trousers.[62]

In 2017, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints announced that its female employees could wear "professional pantsuits and dress slacks" while at work; dresses and skirts had previously been required.[63] In 2018 it was announced that female missionaries of that church could wear dress slacks except when attending the temple and during Sunday worship services, baptismal services, and mission leadership and zone conferences.[64]

In 2019, Virgin Atlantic began to allow its female flight attendants to wear trousers.[65]

Parts of trousers

[edit]

Pleats

[edit]Pleats are located just below the waistband on the front typify many styles of formal and casual trousers, including suit trousers and khakis. There may be one, two, three, or no pleats, which may face either direction. When the pleats open toward the pockets they are called reverse pleats (typical of most trousers today) and when they open toward the fly they are known as forward pleats.[66]

Pockets

[edit]In modern trousers, men's models generally have pockets for carrying small items such as wallets, keys or mobile phones, but women's trousers often do not – and sometimes have what are called Potemkin pockets, a fake slit sewn shut.[67] If there are pockets, they are often much smaller than in men's clothes.[67] In 2018, journalists at The Pudding found less than half of women's front pockets could fit a thin wallet, let alone a handheld phone and keys.[67][68] 'On average, the pockets in women's jeans are 48% shorter and 6.5% narrower than men's pockets.'[68] This gender difference is usually explained by diverging priorities; as French fashion designer Christian Dior allegedly said in 1954: 'Men have pockets to keep things in, women for decoration.'[68]

Cuffs/Bottom hem

[edit]Trouser-makers can finish the legs by hemming the bottom to prevent fraying. Trousers with turn-ups (cuffs in American English), after hemming, are rolled outward and sometimes pressed or stitched into place.[66]

Fly

[edit]A fly is a covering over an opening join concealing the mechanism, such as a zipper, velcro, or buttons, used to join the opening. In trousers, this is most commonly an opening covering the groin, which makes the pants easier to put on or take off. The opening also allows men to urinate without lowering their trousers.[citation needed]

Trousers have varied historically in whether or not they have a fly. Originally, hose did not cover the area between the legs. This was instead covered by a doublet or by a codpiece. When breeches were worn, during the Regency period for example, they were fall-fronted (or broad fall). Later, after trousers (pantaloons) were invented, the fly-front (split fall) emerged.[69] The panelled front returned as a sporting option, such as in riding breeches, but is now hardly ever used, a fly being by far the most common fastening.[70] Most flies now use a zipper, though button-fly pants continue to be available.[66]

Trouser support

[edit]At present, most trousers are held up through the assistance of a belt which is passed through the belt loops on the waistband of the trousers. However, this was traditionally a style acceptable only for casual trousers and work trousers; suit trousers and formal trousers were suspended by the use of braces (suspenders in American English) attached to buttons located on the interior or exterior of the waistband. Today, this remains the preferred method of trouser support amongst adherents of classical British tailoring. Many men claim this method is more effective and more comfortable because it requires no cinching of the waist or periodic adjustment.[citation needed]

Society

[edit]In modern Western society, males customarily wear trousers and not skirts or dresses. There are exceptions, however, such as the ceremonial Scottish kilt and Greek fustanella, as well as robes or robe-like clothing such as the cassocks of clergy and the academic robes, both rarely worn today in daily use. (See also Men's skirts.)

Among certain groups, low-rise, baggy trousers exposing underwear became fashionable; for example, among skaters and in 1990s hip hop fashion. This fashion is called sagging or, alternatively, "busting slack".[71]

Cut-offs are homemade shorts made by cutting the legs off trousers, usually after holes have been worn in fabric around the knees. This extends the useful life of the trousers. The remaining leg fabric may be hemmed or left to fray after being cut.[citation needed]

Religion

[edit]Based on Deuteronomy 22:5 in the Bible ("The woman shall not wear that which pertaineth unto a man"), some groups, including the Amish, Hutterites, some Mennonites, some Baptists, a few Church of Christ groups, and most Orthodox Jews, believe that women should not wear trousers. These groups permit women to wear underpants as long as they are hidden.[citation needed] By contrast, many Muslim sects approve of pants as they are considered more modest than any skirt that is shorter than ankle length. However, some mosques require ankle length trousers for both Muslims and non-Muslims on the premises.[72]

The Catholic Pope Nicholas I approved of both men and women wearing pants. In 866, he wrote in response to the Bulgar Kahn St Boris the Baptiser, "For whether you or your women wear or do not wear pants neither impedes your salvation nor leads to any increase of your virtue." He then proceeded to expound the virtue of wearing the "spiritual pants" in the form of a temperate life while restraining disordered passions.[73]

Laws

[edit]France

[edit]In 2013, a law requiring women in Paris to ask permission from city authorities before "dressing as men", including wearing trousers (with exceptions for those "holding a bicycle handlebar or the reins of a horse") was declared officially revoked by France's Women's Rights Minister, Najat Vallaud-Belkacem.[60] The bylaw was originally intended to prevent women from wearing the pantalons fashionable with Parisian rebels in the French Revolution.[60]

India

[edit]In 2014, an Indian family court in Mumbai ruled that a husband objecting to his wife wearing a kurta and jeans and forcing her to wear a sari amounts to cruelty inflicted by the husband and can be a ground to seek divorce.[61] The wife was thus granted a divorce on the ground of cruelty as defined under section 27(1)(d) of Special Marriage Act, 1954.[61]

Italy

[edit]In Rome in 1992, a 45-year-old driving instructor was accused of rape. When he picked up an 18-year-old for her first driving lesson, he allegedly raped her for an hour, then told her that if she was to tell anyone he would kill her. Later that night she told her parents and her parents agreed to help her press charges. While the alleged rapist was convicted and sentenced, the Supreme Court of Cassation overturned the conviction in 1998 because the victim wore tight jeans. It was argued that she must have necessarily have had to help her attacker remove her jeans, thus making the act consensual ("because the victim wore very, very tight jeans, she had to help him remove them...and by removing the jeans...it was no longer rape but consensual sex"). The court stated in its decision "it is a fact of common experience that it is nearly impossible to slip off tight jeans even partly without the active collaboration of the person who is wearing them."[74] This ruling sparked widespread feminist protest. The day after the decision, women in the Italian Parliament protested by wearing jeans and holding placards that read "Jeans: An Alibi for Rape". As a sign of support, the California Senate and Assembly followed suit. Soon Patricia Giggans, executive director of the Los Angeles Commission on Assaults Against Women, (now Peace Over Violence) made Denim Day an annual event. As of 2011 at least 20 U.S. states officially recognize Denim Day in April. Wearing jeans on this day, 22 April, has become an international symbol of protest.[citation needed] In 2008 the Supreme Court of Cassation overturned the ruling, so there is no longer a "denim" defense to the charge of rape.[75]

Malawi

[edit]In Malawi, women were not legally allowed to wear trousers under President Kamuzu Banda's rule until 1994.[52] This law was introduced in 1965.[53]

Puerto Rico

[edit]In 1919, Luisa Capetillo challenged mainstream society by becoming the first woman in Puerto Rico to wear trousers in public. Capetillo was sent to jail for what was then considered to be a crime, but, the judge later dropped the charges against her.[citation needed]

Turkey

[edit]In 2013, Turkey's parliament ended a ban on women lawmakers wearing trousers in its assembly.[59]

Sudan

[edit]In Sudan, Article 152 of the Memorandum to the 1991 Penal Code prohibits the wearing of "obscene outfits" in public. This law has been used to arrest and prosecute women wearing trousers. Thirteen women including journalist Lubna al-Hussein were arrested in Khartoum in July 2009 for wearing trousers; ten of the women pleaded guilty and were flogged with ten lashes and fined 250 Sudanese pounds apiece. Lubna al-Hussein considers herself a good Muslim and asserts "Islam does not say whether a woman can wear trousers or not. I'm not afraid of being flogged. It doesn't hurt. But it is insulting." She was eventually found guilty and fined the equivalent of $200 rather than being flogged.[55]

United States

[edit]In May 2004, in Louisiana, Democrat and state legislator Derrick Shepherd proposed a bill that would make it a crime to appear in public wearing trousers below the waist and thereby exposing one's skin or "intimate clothing".[76] The Louisiana bill did not pass.[citation needed]

In February 2005, Virginia legislators tried to pass a similar law that would have made punishable by a $50 fine "any person who, while in a public place, intentionally wears and displays his below-waist undergarments, intended to cover a person's intimate parts, in a lewd or indecent manner". (It is not clear whether, with the same coverage by the trousers, exposing underwear was considered worse than exposing bare skin, or whether the latter was already covered by another law.) The law passed in the Virginia House of Delegates. However, various criticisms to it arose. For example, newspaper columnists and radio talk show hosts consistently said that since most people that would be penalized under the law would be young African-American men, the law would thus be a form of racial discrimination. Virginia's state senators voted against passing the law.[77][78]

In California, Government Code Section 12947.5 (part of the California Fair Employment and Housing Act (FEHA)) expressly protects the right to wear pants.[79] Thus, the standard California FEHA discrimination complaint form includes an option for "denied the right to wear pants".[80]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Hanks, Patrick, ed. (1979). Collins English Dictionary. London: Collins. p. 1061. ISBN 978-0-00-433078-5.

pants pl. n. 1. British. an undergarment reaching from the waist to the thighs or knees. 2. the usual U.S. name for trousers.

- ^ Mayke Wagner; Moa Hallgren-Brekenkamp, Dongliang Xu, Xiaojing Kang, Patrick Wertmann, Carol James, Irina Elkina, Dominic Hosner, Christian Leipeg, Pavel E.Tarasovh, "The invention of twill tapestry points to Central Asia: Archaeological record of multiple textile techniques used to make the woollen outfit of a ca. 3000-year-old horse rider from Turfan, China", Archaeological Research in Asia, Volume 29, March 2022, 100344, doi:10.1016/j.ara.2021.100344.

- ^ a b Smith, Kiona N., "The world's oldest pants are a 3,000-year-old engineering marvel", Ars Technica, 4 April 2022.

- ^ a b Beck, Ulrike; Wagner, Mayke; Li, Xiao; Durkin-Meisterernst, Desmond; Tarasov, Pavel E. (22 May 2014). "The invention of trousers and its likely affiliation with horseback riding and mobility: A case study of late 2nd millennium BC finds from Turfan in eastern Central Asia". Quaternary International. 348: 224–235. Bibcode:2014QuInt.348..224B. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2014.04.056. ISSN 1040-6182.

- ^ a b Beck, Ulrike; Wagner, Mayke; Li, Xiao; Durkin-Meisterernst, Desmond; Tarasov, Pavel E. (2014). "First pants worn by horse riders 3,000 years ago". Quaternary International. 348. Science News: 224–235. Bibcode:2014QuInt.348..224B. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2014.04.056. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ "The History and Tradition of Highland Dancing". Historic UK. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ Mackenzie, Laurel; Bailey, George; Danielle, Turton (2016). "Our Dialects: Mapping variation in English in the UK". www.ourdialects.uk. University of Manchester. Lexical Variation > Clothing. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ "Pair of pants". World Wide Words. 28 April 2001. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ Nelson, Sarah M. (2004). Gender in archaeology: analyzing power and prestige. Gender and Archaeology. Vol. 9. Rowman Altamira. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-7591-0496-9.

- ^ "AS old As a History*". persianwondersvideo.blogspot.com.au.

- ^ Payne, Blanche. History of Costume. Harper & Row, 1965. pp. 49–51

- ^ Sekunda, Nicholas. The Persian Army 560–330 BC. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- ^ Lever, James (1995, 2010). Costume and Fashion: A Concise History. Thames and Hudson. p. 15.

- ^ ἀναξυρίδες, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ^ σαράβαρα, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ^ Euripides, Cyclops, 182

- ^ Aristophanes, Wasps, 1087

- ^ θύλακος, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ^ Lever, James. Costume and Fashion: A Concise History. Thames and Hudson, 1995, 2010. p. 50.

- ^ Payne, Blanche (1965). History of Costume. Harper & Row. p. 97

- ^ "Feminalia.", The Fashion Encyclopedia. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ "Braccae - Fashion, Costume, and Culture: Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear through the Ages". Fashionencyclopedia.com. 24 July 2003. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ Lever, James (1995, 2010). Costume and Fashion: A Concise History. Thames and Hudson. p. 40.

- ^ Payne, Blanche. History of Costume. Harper & Row, 1965. p. 124

- ^ Payne, Blanche. History of Costume. Harper & Row, 1965. Pp. 136–138

- ^ Lever, James. Costume and Fashion: A Concise History. Thames and Hudson, 1995, 2010. p. 51.

- ^ Payne, Blanche. History of Costume. Harper & Row, 1965. p. 142

- ^ Payne, Blanche. History of Costume. Harper & Row, 1965. pp. 142, 154

- ^ Einhard. The Life of Charlemagne. University of Michigan Press, 1960.

- ^ Lever, James. Costume and Fashion: A Concise History. Thames and Hudson, 1995, 2010. pp. 50–51.

- ^ Payne, Blanche. History of Costume. Harper & Row, 1965. p. 180

- ^ Lever, James. Costume and Fashion: A Concise History. Thames and Hudson, 1995, 2010. p. 58.

- ^ Payne, Blanche. History of Costume. Harper & Row, 1965. p. 207

- ^ Payne, Blanche. History of Costume. Harper & Row, 1965. p. 200

- ^ "Pannonian Renaissance". Mek.oszk.hu. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ "Edicts and Decrees". Cengage Learning. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- ^ Italian Culture in the Drama of Shakespeare and His Contemporaries, ed. Michele Marrapodi 2007

- ^ "Empire/Directoire Image Review-Men". Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ^ "History: Regency Origins". Black Tie Guide. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ^ "Beau Tie: The Legacy of Beau Brummell, Inventor of the Modern Suit". Mjbale.com. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ^ Gill, Eric (1937). Trousers & The Most Precious Ornament. London: Faber and Faber. OCLC 5034115.

- ^ "The History of Denim". FragranceX. February 2019.

- ^ Lee, Kyung Ja, and Hong Na Young and Chang Sook Hwan, translated by Shin Jooyoung. Traditional Korean Costume. Global Orient, 2003 p. 231.

- ^ "Trousers for Women". Fashionencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ "Clothing3". World War 2 Ex RAF. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ "Update: First woman to wear pants on House floor, Rep. Charlotte Reid". The Washington Post. 21 December 2011.

- ^ "First Lady - Pat Nixon | C-SPAN First Ladies: Influence & Image". Firstladies.c-span.org. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ^ "A first: Woman senator dons pants". Lodi News-Sentinel. UPI. 7 February 1989.

- ^ "Flashback: Top 7 Hillary Rodham Clinton pant suits". Rare. 8 June 2021.

- ^ a b Givhan, Robin (21 January 2004). "Moseley Braun: Lady in red". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ a b "The Long and Short of Capitol Style". Roll Call.

- ^ a b Sarah DeCapua, Malawi in Pictures, 2009, pg 7.

- ^ a b "Malawi-vroue mag broek dra" [Malawi: Women may wear pants]. Beeld (in Afrikaans). Johannesburg. 1 December 1993. p. 9. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ "Slovak Pair Tests New ISU Costume Rules". Skate Today. 5 December 2004. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ a b Gettleman, Jeffrey; Arafat, Waleed (8 September 2009). "Sudan Court Fines Woman for Wearing Trousers". The New York Times.

- ^ Moore, Dene (16 August 2012). "Female Mounties earn right to wear pants and boots with all formal uniforms". The Vancouver Sun. The Canadian Press. Retrieved 16 January 2025.

- ^ Gryboski, Michael (16 December 2013). "Mormon Women Observe 'Wear Pants to Church' Sunday to Promote Gender Equality". Christian Post.

- ^ a b Seid, Natalie (14 December 2013). "LDS Women Suit Up For Second 'Wear Pants to Church Day'". Boise Weekly. Archived from the original on 8 April 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ^ a b "Turkey lifts ban on trousers for women MPs in parliament". Yahoo! News. 14 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d "It Is Now Legal for Women to Wear Pants in Paris". Time. New York. 4 February 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Wife's jeans ban is grounds for divorce, India court rules". Gulf News. Dubai. PTI. 28 June 2014. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- ^ "Because It Is 2016, British Airways Finally Agrees Female Employees May Wear Pants To Work". ThinkProgress. 6 February 2016.

- ^ Dalrymple II, Jim (30 June 2017). "The Mormon Church Just Allowed Female Employees To Wear Pants. Here's Why That's A Big Deal". Buzzfeed News. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ^ "Female Mormon missionaries given option to wear dress slacks". News 95.5 and AM750 WSB. 20 December 2018. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- ^ Yeginsu, Ceylan (5 March 2019). "Virgin Atlantic Won't Make Female Flight Attendants Wear Makeup or Skirts Anymore". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- ^ a b c "Parts of trousers". ENGLISH FOR TAILORS. Retrieved 26 November 2024.

- ^ a b c Clark, Pilita (7 November 2022). "Women are big losers in the politics of pockets". Financial Times. Retrieved 10 November 2022.

- ^ a b c Diehm, Jan; Thomas, Amber (August 2018). "Women's Pockets are Inferior". The Pudding. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- ^ Croonborg, Frederick: The Blue Book of Men's Tailoring. Croonborg Sartorial Co. New York and Chicago, 1907. p. 123

- ^ "Button Fly Jeans". www.apparelsearch.com. Retrieved 26 November 2024.

- ^ "Huckaby: Pants off to the kids busting slack at school". Online Athens. 26 August 2007. Archived from the original on 4 December 2015. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ "Mosque Manners : Dress Code". Szgmc.ae. Archived from the original (JPG) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ Murphy, Conrad. "St. Nicholas I And The Question Of Trousers". Catholic Link. Catholic-Link.org. Archived from the original on 15 January 2025. Retrieved 20 January 2025.

- ^ Faedi, Benedetta (2009). "Rape, Blue Jeans, and Judicial Developments in Italy". Columbia Journal of European Law. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ Owen, Richard (23 July 2008). "Italian court reverses 'tight jeans' rape ruling". Irish Independent. Dublin. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ "House Bill number 1626" (PDF). Legislature of Louisiana. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2004. Retrieved 30 September 2009.

It shall be unlawful for any person to appear in public wearing his pants below his waist and thereby exposing his skin or intimate clothing.

- ^ "Bill Tracking - 2005 session : Legislation". Leg1.state.va.us. 4 February 2005. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ "LOCI-HEREIN:A Blog About Today And Tomorrow, With Insights From Yesterday.: 50 bucks to Freeball".

- ^ "California Government Code - GOV § 12947.5". Codes.lp.findlaw.com. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ "Instructions for Obtaining a Right-to-Sue Notice" (PDF). California Department Of Fair Employment & Housing. July 2021. p. 5. DFEH-IF903-7X-ENG. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

I ALLEGE THAT I EXPERIENCED: [...] AS A RESULT I WAS: Denied the right to wear pants

External links

[edit] Quotations related to Trousers at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Trousers at Wikiquote The dictionary definition of trousers at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of trousers at Wiktionary Media related to Trousers at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Trousers at Wikimedia Commons- (video) Etymology of 'Pants', from Mysteries of Vernacular Archived 1 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- (video) The Invention of the Trousers, from German Archaeological Institute