Mal'ta–Buret' culture

Location of Mal'ta–Buret' | |

| Geographical range | Irkutsk Oblast, Siberia, Russian Federation |

|---|---|

| Period | Upper Paleolithic |

| Dates | 24,000–15,000 BP |

| Type site | Site of Mal'ta (52°51′00″N 103°31′03″E / 52.850045°N 103.517383°E)[1] Site of Buret' (approx. 53°00′10″N 103°30′31″E / 53.002647°N 103.508696°E) |

| Preceded by | Mousterian (Denisova Cave)[2] Aurignacian? |

| Followed by | Afontova Gora |

The Mal'ta–Buret' culture (also Maltinsko-buretskaya culture) is an archaeological culture of the Upper Paleolithic (generally dated to 24,000-23,000 BP but also sometimes to 15,000 BP).[5] It is located roughly northwest of Lake Baikal, about 90km to the northwest of Irkutsk, on the banks of the upper Angara River.

The type sites are named for the villages of Mal'ta (Мальта́), Usolsky District and Buret' (Буре́ть), Bokhansky District (both in Irkutsk Oblast).

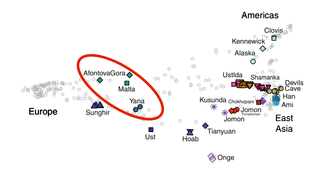

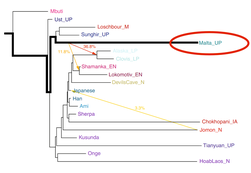

A boy whose remains were found near Mal'ta is usually known by the abbreviation MA-1 (or MA1). Discovered in the 1920s, the remains have been dated to 24,000 BP. According to research published since 2013, MA-1 belonged to the population of Ancient North Eurasians, who were genetically "intermediate between modern western Eurasians and Native Americans, but distant from east Asians",[6] and partial genetic ancestors of Siberians, American Indians, and Bronze Age Yamnaya and Botai[7] people of the Eurasian steppe.[8][9] In particular, modern-day Native Americans, Kets, Mansi, and Selkup have been found to harbour a significant amount of ancestry related to MA-1.[10]

Much of what is known about Mal'ta comes from the Russian archaeologist Mikhail Gerasimov. Better known later for his contribution to the branch of anthropology known as forensic facial reconstruction, Gerasimov made revolutionary discoveries when he excavated Mal'ta in 1927. Until his findings, the Upper Paleolithic societies of Northern Asia were virtually unknown. Over the remainder of his career, Gerasimov twice more visited Mal'ta to excavate and research the site.

Material culture

[edit]Habitation and tools

[edit]

Mal'ta consists of semi-subterranean houses that were built using large animal bones to assemble the walls, and reindeer antlers covered with animal skins to construct a roof that would protect the inhabitants from the harsh elements of the Siberian weather.[12] These dwellings built from mammoth bones were similar to those found in Upper Paleolithic Western Eurasia, such as in the areas of France, Czechoslovakia, and Ukraine.[11]

Evidence seems to indicate that Mal'ta is the most ancient known site in eastern Siberia, with the nearby site of Buret'.[12][13] However, relative dating illustrates some irregularities. The use of flint flaking and the absence of pressure flaking used in the manufacture of tools, as well as the continued use of earlier forms of tools, seem to confirm the fact that the site belongs to the early Upper Paleolithic. Yet it lacks typical skreblos (large side scrapers) that are common in other Siberian Paleolithic sites. Additionally, other common characteristics such as pebble cores, wedge-shaped cores, burins, and composite tools have never been found. The lack of these features, combined with an art style found in only one other nearby site (the Venus of Buret'), make Mal'ta culture unique in Siberia.

Art

[edit]There were two main types of art during the Upper Paleolithic: mural art, which was concentrated in Western Europe, and portable art. Portable art, typically some type of carving in ivory tusk or antler, spans the distance across Western Europe into Northern and Central Asia. Artistic remains of expertly carved bone, ivory, and antler objects depicting birds and human females are the most commonly found; these objects are, collectively, the primary source of Mal'ta's acclaim.[12]

In addition to the female statuettes there are bird sculptures depicting swans, geese, and ducks. Through ethnographic analogy comparing the ivory objects and burials at Mal'ta with objects used by 19th and 20th-century Siberian shamans, it has been suggested that they are evidence of a fully developed shamanism.

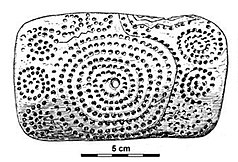

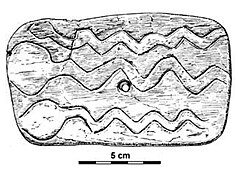

Also, there are engraved representations on slabs of mammoth tusk. One is the figure of a mammoth, easily recognizable by the trunk, tusks, and thick legs. Wool also seems to be etched, by the placement of straight lines along the body. Another drawing depicts three snakes with their heads puffed up and turned to the side. It is believed that they were similar to cobras.

Venus figurines

[edit]

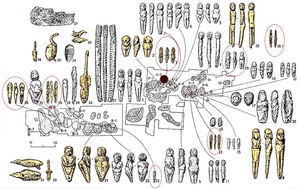

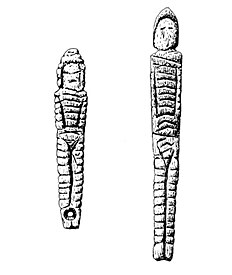

Perhaps the best example of Paleolithic portable art is something referred to as "Venus figurines".[12] The Mal'ta boy (dated 24,000 BP) was buried with various artefacts and a Venus figurine.[20] Until they were discovered in Mal'ta, "Venus figurines" were previously found only in Europe.[12] Carved from the ivory tusk of a mammoth, these images were typically highly stylized, and often involved embellished and disproportionate characteristics (typically the breasts or buttocks). It is widely believed that these emphasized features were meant to be symbols of fertility. Around thirty female statuettes of varying shapes have been found in Mal'ta. The wide variety of forms, combined with the realism of the sculptures and the lack of repetitiveness in detail, are definite signs of developed, albeit early, art.

At first glance, what is obvious is that the Mal'ta Venus figurines are of two types: full-figured women with exaggerated forms, and women with a thin, delicate form. Some of the figures are nude, while others have etchings that seem to indicate fur or clothing. Conversely, unlike those found in Europe, some of the Venus figurines from Mal'ta were sculpted with faces. Most of the figurines were tapered at the bottom, and it is believed that this was done to enable them to be stuck into the ground or otherwise placed upright. Placed upright, they could have symbolized the spirits of the dead, akin to "spirit dolls" used nearly worldwide, including in Siberia, among contemporary people.

Context of the Venus figurines

[edit]

The Mal'ta figurines garner interest in the western world because they seem to be of the same basic form as European female figurines of roughly the same time period, suggestion some cultural and cultic connection.[12] This similarity between Mal'ta and Upper Paleolithic Europe coincides with other suggested similarities between the two, such as in their tools and dwelling structures.

A 2016 genomic study shows that the Mal'ta people have no genetic connections to the Dolní Věstonice people from the Gravettian culture. The researchers conclude that the similarity between the figurines may be either due to cultural diffusion or to a coincidence, but not to common ancestry between the populations.[23]

Symbolism

[edit]Discussing this easternmost outpost of paleolithic culture, Joseph Campbell finishes by commenting on the symbolic forms of the artifacts found there:

We are clearly in a paleolithic province where the serpent, labyrinth, and rebirth themes already constitute a symbolic constellation, joined with the imagery of the sunbird and shaman flight, with the goddess in her classic role of protectress of the hearth, mother of man's second birth, and lady of wild things and of the food supply.[24]

Archaeogenetics

[edit]

MA-1 is the only known example of basal Y-DNA R* (R-M207*) – that is, the only member of haplogroup R* that did not belong to haplogroups R1, R2 or secondary subclades of these. The mitochondrial DNA of MA-1 belonged to an unresolved subclade of haplogroup U.[25]

The remains of the Mal'ta boy (MA-1) are currently in the Hermitage Museum (Saint-Petersburg).

-

Mal'ta boy (MA-1), dated 24,000 BP, with tomb artifacts, Hermitage Museum, Saint-Petersburg.[26]

-

Grave artifacts of the Mal'ta boy (MA-1)

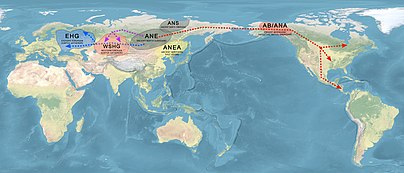

The term Ancient North Eurasian (ANE) has been given in genetic literature to an ancestral component that represents descent from the people similar to the Mal'ta–Buret' culture and the closely related population of Afontova Gora.[10][27]

A people similar to MA1 and Afontova Gora were important genetic contributors to Native Americans, Siberians, Europeans, Caucasians, Central Asians, with smaller contributions to Middle Easterners and some East Asians.[28] Lazaridis et al. (2016) notes "a cline of ANE ancestry across the east-west extent of Eurasia."[28] The "ANE-cline", as observed among Paleolithic Siberian populations and their direct descendants, developed from a sister lineage of Europeans with significant admixture from early East Asians.[29][30]

MA1 is also related to two older Upper Paleolithic Siberian individuals found at the Yana Rhinoceros Horn Site called Ancient North Siberians (ANS).[31]

References

[edit]- ^ Lbova, Liudmila (2021). "The Siberian Palaeolithic Site of Mal'ta: A Unique Source for The Study of Childhood Archaeology". Evolutionary Human Sciences: Fig. 1-3.

- ^ Fagan, Brian M. (5 December 1996). The Oxford Companion to Archaeology. Oxford University Press. p. 644. ISBN 978-0-19-977121-9.

- ^ "Plate with the image of mammoth". Art of Mal'ta. Novosibirsk State University.

- ^ The mammoth engraving is item 37 in this inventory

- ^ Bednarik, Robert G. (2013). "Pleistocene Palaeoart of Asia". Arts. 2 (2): 48. doi:10.3390/arts2020046.

- ^ Raghavan, Maanasa (2014). "Upper Palaeolithic Siberian genome reveals dual ancestry of Native Americans". Nature. 505 (7481): 87–91. Bibcode:2014Natur.505...87R. doi:10.1038/nature12736. PMC 4105016. PMID 24256729.

In the first two principal components, MA-1 is intermediate between modern western Eurasians and Native Americans, but distant from east Asians

- ^ a b Jeong, Choongwon; Balanovsky, Oleg; Lukianova, Elena; Kahbatkyzy, Nurzhibek; Flegontov, Pavel; Zaporozhchenko, Valery; Immel, Alexander; Wang, Chuan-Chao; Ixan, Olzhas; Khussainova, Elmira; Bekmanov, Bakhytzhan; Zaibert, Victor; Lavryashina, Maria; Pocheshkhova, Elvira; Yusupov, Yuldash; Agdzhoyan, Anastasiya; Sergey, Koshel; Bukin, Andrei; Nymadawa, Pagbajabyn; Churnosov, Michail; Skhalyakho, Roza; Daragan, Denis; Bogunov, Yuri; Bogunova, Anna; Shtrunov, Alexandr; Dubova, Nadezda; Zhabagin, Maxat; Yepiskoposyan, Levon; Churakov, Vladimir; Pislegin, Nikolay; Damba, Larissa; Saroyants, Ludmila; Dibirova, Khadizhat; Artamentova, Lubov; Utevska, Olga; Idrisov, Eldar; Kamenshchikova, Evgeniya; Evseeva, Irina; Metspalu, Mait; Robbeets, Martine; Djansugurova, Leyla; Balanovska, Elena; Schiffels, Stephan; Haak, Wolfgang; Reich, David; Krause, Johannes (23 May 2018). "Characterizing the genetic history of admixture across inner Eurasia". bioRxiv 10.1101/327122.

Ancient DNA studies have already shown that human populations of this region have dramatically transformed over time. For example, the Upper Paleolithic genomes from the Mal'ta and Afontova Gora archaeological sites in southern Siberia revealed a genetic profile, often referred to as "Ancient North Eurasians (ANE)", which is deeply related to Paleolithic/Mesolithic hunter-gatherers in Europe and also substantially contributed to the gene pools of modern-day Native Americans, Siberians, Europeans and South Asians.

- ^ Raghavan & Skoglund et al. 2014.

- ^ Haak & Lazaridis et al. 2015.

- ^ a b Flegontov & Changmai et al. 2015.

- ^ a b Dolitsky, Alexander B.; Ackerman, Robert E.; Aigner, Jean S.; Bryan, Alan L.; Dennell, Robin; Guthrie, R. Dale; Hoffecker, John F.; Hopkins, David M.; Lanata, José Luis; Workman, William B. (1985). "Siberian Paleolithic Archaeology: Approaches and Analytic Methods [and Comments and Replies]". Current Anthropology. 26 (3): 361–378. doi:10.1086/203280. ISSN 0011-3204. JSTOR 2742734. S2CID 147371671.

The Upper Paleolithic inhabitants of the European region spanned by France, Czechoslovakia, and the Ukraine led a hunting life resembling that of the people of Mal'ta and Buret' and built similar dwellings of matching construction from the bones of extinct large mammals

- ^ a b c d e f Tedesco, Laura Anne. "Mal'ta (ca. 20,000 B.C.)". The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ Karen Diane Jennett (May 2008). "Female Figurines of the Upper Paleolithic" (PDF). Texas State University. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

- ^ Lbova, Liudmila (2021). "The Siberian Palaeolithic Site of Mal'ta: A Unique Source for The Study of Childhood Archaeology". Evolutionary Human Sciences. 3. doi:10.1017/ehs.2021.5. PMC 10427291. S2CID 231980510.

- ^ Photograph: "Miniature sculpture of a teenager in overalls". Art of Mal'ta. Novosibirsk State University.

- ^ a b c Bednarik, Robert G. (2013). "Pleistocene Palaeoart of Asia". Arts. 2 (2): 46-76. doi:10.3390/arts2020046.

- ^ Photograph: "Figurine of dressed teenager". Art of Mal'ta. Novosibirsk State University.

- ^ Photograph: "Anthropomphic figurine (Buret')". Art of Mal'ta. Novosibirsk State University.

- ^ [1]

- ^ "Ancient DNA from Siberian boy links Europe and America". BBC News. 20 November 2013.

- ^ "Ancient DNA from Siberian boy links Europe and America". BBC News. 20 November 2013.

- ^ Lbova, Liudmila; Volkov, Pavel (1 June 2016). "Processing technology for the objects of mobile art in the Upper Paleolithic of Siberia (the Malta site)". Quaternary International. 403: 17. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.10.019. ISSN 1040-6182.

- ^ Fu, Qiaomei; Posth, Cosimo; et al. (May 2, 2016). "The genetic history of Ice Age Europe". Nature. 504 (7606): 200–5. Bibcode:2016Natur.534..200F. doi:10.1038/nature17993. hdl:10211.3/198594. PMC 4943878. PMID 27135931.

- ^ Campbell, Joseph (1987). Primitive Mythology. pp. 331. ISBN 0-14-019443-6.

- ^ Raghavan, Maanasa; Skoglund, Pontus; Graf, Kelly E.; Metspalu, Mait; Albrechtsen, Anders; Moltke, Ida; Rasmussen, Simon; Stafford Jr, Thomas W.; Orlando, Ludovic; Metspalu, Ene; Karmin, Monika; Tambets, Kristiina; Rootsi, Siiri; Mägi, Reedik; Campos, Paula F.; Balanovska, Elena; Balanovsky, Oleg; Khusnutdinova, Elza; Litvinov, Sergey; Osipova, Ludmila P.; Fedorova, Sardana A.; Voevoda, Mikhail I.; DeGiorgio, Michael; Sicheritz-Ponten, Thomas; Brunak, Søren; Demeshchenko, Svetlana; Kivisild, Toomas; Villems, Richard; Nielsen, Rasmus; Jakobsson, Mattias; Willerslev, Eske (January 2014). "Upper Palaeolithic Siberian genome reveals dual ancestry of Native Americans". Nature. 505 (7481): 87–91. Bibcode:2014Natur.505...87R. doi:10.1038/nature12736. PMC 4105016. PMID 24256729.

- ^ Lbova, Liudmila (2021). "The Siberian Paleolithic site of Mal'ta: a unique source for the study of childhood archaeology". Evolutionary Human Sciences. 3: 8, Fig. 6-1. doi:10.1017/ehs.2021.5. S2CID 231980510.

- ^ Lazaridis, Iosif; Nadel, Dani; Rollefson, Gary; et al. (16 June 2016). "Genomic insights into the origin of farming in the ancient Near East". Nature. 536 (7617): 419–424. Bibcode:2016Natur.536..419L. bioRxiv 10.1101/059311. doi:10.1038/nature19310. PMC 5003663. PMID 27459054.

- ^ a b Lazaridis et al. 2016, p. 10.

- ^ Vallini et al. 2022, Supplementary Information, p. 17: "Paleolithic Siberian populations younger than 40 ky are consistently described as a mix of European and East Asian ancestries".

- ^ Villalba-Mouco, Vanessa; van de Loosdrecht, Marieke S.; Rohrlach, Adam B.; Fewlass, Helen; Talamo, Sahra; Yu, He; Aron, Franziska; Lalueza-Fox, Carles; Cabello, Lidia; Cantalejo Duarte, Pedro; Ramos-Muñoz, José; Posth, Cosimo; Krause, Johannes; Weniger, Gerd-Christian; Haak, Wolfgang (2023-03-01). "A 23,000-year-old southern Iberian individual links human groups that lived in Western Europe before and after the Last Glacial Maximum". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 7 (4): 597–609. doi:10.1038/s41559-023-01987-0. ISSN 2397-334X. PMC 10089921. PMID 36859553.

This is because the ancestry found in Mal'ta and Afontova Gora individuals (Ancient North Eurasian ancestry) received ancestry from UP East Asian/Southeast Asian populations54, who then contributed substantially to EHG55.

- ^ Sikora, Martin; Pitulko, Vladimir V.; Sousa, Vitor C.; Allentoft, Morten E.; Vinner, Lasse; Rasmussen, Simon; Margaryan, Ashot; de Barros Damgaard, Peter; de la Fuente, Constanza; Renaud, Gabriel; Yang, Melinda A.; Fu, Qiaomei; Dupanloup, Isabelle; Giampoudakis, Konstantinos; Nogués-Bravo, David; Rahbek, Carsten; Kroonen, Guus; Peyrot, Michaël; McColl, Hugh; Vasilyev, Sergey V.; Veselovskaya, Elizaveta; Gerasimova, Margarita; Pavlova, Elena Y.; Chasnyk, Vyacheslav G.; Nikolskiy, Pavel A.; Gromov, Andrei V.; Khartanovich, Valeriy I.; Moiseyev, Vyacheslav; Grebenyuk, Pavel S.; Fedorchenko, Alexander Yu; Lebedintsev, Alexander I.; Slobodin, Sergey B.; Malyarchuk, Boris A.; Martiniano, Rui; Meldgaard, Morten; Arppe, Laura; Palo, Jukka U.; Sundell, Tarja; Mannermaa, Kristiina; Putkonen, Mikko; Alexandersen, Verner; Primeau, Charlotte; Baimukhanov, Nurbol; Malhi, Ripan S.; Sjögren, Karl-Göran; Kristiansen, Kristian; Wessman, Anna; Sajantila, Antti; Lahr, Marta Mirazon; Durbin, Richard; Nielsen, Rasmus; Meltzer, David J.; Excoffier, Laurent; Willerslev, Eske (June 2019). "The population history of northeastern Siberia since the Pleistocene" (PDF). Nature. 570 (7760): 182–188. Bibcode:2019Natur.570..182S. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1279-z. PMID 31168093. S2CID 174809069.

- ^ a b Gakuhari, Takashi; Nakagome, Shigeki; Rasmussen, Simon; Allentoft, Morten E. (25 August 2020). "Ancient Jomon genome sequence analysis sheds light on migration patterns of early East Asian populations". Communications Biology. 3 (1): Fig.1 A, B. doi:10.1038/s42003-020-01162-2. ISSN 2399-3642. PMC 7447786. PMID 32843717.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bednarik, Robert G. (1994). "The Pleistocene Art of Asia". Journal of World Prehistory. 8 (4): 351–75. doi:10.1007/bf02221090. S2CID 161683955.

- Chard, Chester S. (1974). Northeast Asia in Prehistory. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299064303.

- Dolitsky, A.B.; Ackerman. R.E.; et al. (1985). "Siberian Paleolithic Archaeology: Approaches and Analytic Methods". Current Anthropology. 26 (3): 361–78. doi:10.1086/203280. S2CID 147371671.

- Flegontov, Pavel; Changmai, Piya; et al. (Feb 11, 2016). "Genomic study of the Ket: a Paleo-Eskimo-related ethnic group with significant ancient North Eurasian ancestry". Scientific Reports. 6: 20768. arXiv:1508.03097. Bibcode:2016NatSR...620768F. doi:10.1038/srep20768. PMC 4750364. PMID 26865217.

- Haak, W.; Lazaridis, I.; et al. (2015). "Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe". Nature. 522 (7555): 207–11. arXiv:1502.02783. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..207H. doi:10.1038/nature14317. PMC 5048219. PMID 25731166.

- Jones, Eppie R.; Gonzalez-Fortes, Gloria; et al. (2015). "Upper Palaeolithic genomes reveal deep roots of modern Eurasians". Nature Communications. 6: 8912. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.8912J. doi:10.1038/ncomms9912. PMC 4660371. PMID 26567969.

- Lazaridis, Iosif; Patterson, Nick; et al. (2014). "Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans". Nature. 513 (7518): 409–13. arXiv:1312.6639. Bibcode:2014Natur.513..409L. doi:10.1038/nature13673. PMC 4170574. PMID 25230663.

- Martynov, Anatoly I, The Ancient Art of Northern Asia, trans. Demitri B. Shimkin and Edith M. Shimkin. Chicago, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1991.

- Raghavan, Maanasa; Skoglund, Pontus; et al. (2014). "Upper Palaeolithic Siberian Genome Reveals Dual Ancestry of Native Americans". Nature. 505 (7481): 87–91. Bibcode:2014Natur.505...87R. doi:10.1038/nature12736. PMC 4105016. PMID 24256729.

- Schlesier, Karl H (2001). "More on the Venus Figurines". Current Anthropology. 42 (3): 410–412. doi:10.1086/320478. S2CID 162218369.

- Sieveking, Ann (1971). "Palaeolithic Decorated Bone Discs" T". The British Museum Quarterly. 35 (1/4): 206–229. doi:10.2307/4423083. JSTOR 4423083.

- Vallini, Leonardo; Marciani, Giulia; Aneli, Serena; Bortolini, Eugenio; et al. (2022). "Genetics and Material Culture Support Repeated Expansions into Paleolithic Eurasia from a Population Hub Out of Africa". Genome Biology and Evolution. 14 (4). doi:10.1093/gbe/evac045. PMC 9021735. PMID 35445261.

![Mal'ta boy (MA-1), dated 24,000 BP, with tomb artifacts, Hermitage Museum, Saint-Petersburg.[26]](http://up.wiki.x.io/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b5/Mal%27ta_boy_%28MA-1%29_with_tomb_artifacts%2C_Hermitage_Museum%2C_Saint-Petersburg.jpg/198px-Mal%27ta_boy_%28MA-1%29_with_tomb_artifacts%2C_Hermitage_Museum%2C_Saint-Petersburg.jpg)