Tribal assembly

| Politics of the Roman Republic | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

| 509 – 27 BC | ||||||||||

| Constitution and development | ||||||||||

| Magistrates and officials | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Senate | ||||||||||

| Assemblies | ||||||||||

| Public law and norms | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

The tribal assembly (Latin: comitia tributa) was one of the citizens' assemblies of ancient Rome, responsible, along with the plebeian council, for the passage of most Roman laws in the middle and late republics. They were also responsible for the elections of a number of junior magistracies: aediles and quaestors especially.

It organised citizens, by the middle republic, into thirty-five artificial tribes which were assigned by geography. The composition of the tribes packed the urban poor into four tribes out of the thirty-five. The requirement that citizens vote in person also discriminated against the rural poor who were not able to travel to Rome.

Each tribe possessed an internal structure and a single vote in the assembly, regardless of the number of citizens belonging to that tribe and determined by a majority of the citizens of that tribe present at the vote. Legislative proposals passed when a majority of tribes voted in favour; elections continued until a majority of tribes approved of sufficient candidates that all posts were filled.

The tribal assembly and the plebeian council were organised identically. What differed between them was the presiding magistrate, with the tribal assembly convened by consuls, praetors, or aediles and the plebeian council convened by plebeian tribunes. After the lex Hortensia in 287 BC endowed the plebeian council with full legislative powers, the two assemblies became practically identical.[1]

Duties

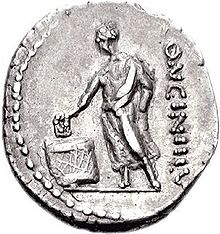

[edit]The comitia tributa in the classical republic was responsible for the election military tribunes, quaestors, and curule aediles. It also had power to enact legislation and try non-capital cases.[2] Because it was simpler than the comitia centuriata, by the middle and late republic, the tribal assembly had become the main form of legislative assembly.[3][4]

Like the other comitia the tribal assembly, as the embodiment of the people, was sovereign.[5] However, the fact that the business brought before it was entirely controlled by the aristocratic magistrates – the people had no right of initiative and could only vote on proposals brought by those magistrates – meant that the people had a largely passive role in the legislative process.[6]

Procedure

[edit]Like the other comitia, the tribes had to be summoned to vote by a magistrate with the right to do so (ius agendi cum populo) on a day on which it was religiously permitted to summon an assembly (a dies comitialis) and after favourable auspices in an inaugurated templum.[2]

The tribes met for legislative and judicial votes in the comitium, a meeting place before the senatorial curia in the forum that could fit between three and four thousand people, prior to 145 BC.[7][8][9] Afterwards it met in the forum or on the Capitoline hill. Elections c. 133 BC occurred on the Capitoline but sometime afterwards, tribal elections were instead conducted on the campus Martius.[10][11] Such changes may have been related to the then-ongoing movement towards secret ballot rather than oral voting.[12]

After some speeches by the presiding magistrate and those he invited, the magistrate ordered citizens to reassemble by tribe.[13] The tribes then voted without any deliberation; any public debate occurred prior to the legislative comitia through duelling contio where magistrates spoke to an unorganised crowd urging them one way or the other on upcoming legislation.[14] Citizens identified themselves to tribal officials (tribules). Prior to the introduction of the secret ballot – in various years between 139 and 107[15] – an official would have received the votes orally; afterwards officials counted wax tablets deposited in turns and returned the results to the presiding magistrate.[16]

Prior to the last quarter of the second century – perhaps 139 BC with the lex Gabinia – the tribes voted sequentially. However, afterwards, they voted simultaneously with the results then announced sequentially.[17] Under the sequential system, a first tribe was selected by lot from among the thirty-one rural tribes.[18] Scholars disagree as to whether the principium acted as an omen of results like the centuria praerogativa in the centuriate assembly.[19] Voting then continued either by lot or by a fixed order of tribes thereafter,[17][20] with the results of each tribe announced as a guide for future voters.[21] When voting became simultaneous, each tribe's vote was announced in a random order.[22]

Application of the lot made the order in which an electoral candidate received votes important, making electoral results partially determined by chance, since all remaining votes were discarded once all posts were filled.[17] The effect of the lot was such that candidates who were more popular among the tribal blocs could be passed over by another candidate who reached a majority more rapidly.[22] In elections, the results became binding when the presiding magistrates completed the task of creating their successors by swearing in the winners.[23]

Turnout in tribal assemblies could at times be extremely low. Cicero, in Pro Sestio, mentions that if a tribe had no voters turn up at all, citizens in other tribes could be transferred by lot to vote for the empty tribe instead.[24] Regardless, estimates of the size of the voting spaces imply maximum voter turnout between 0.66 and 1.85%.[25]

History

[edit]In the historical period the Roman republic had three kinds of citizen assemblies: the curiate, centuriate, and tribal assemblies.[26] The curiae were likely organised by birth; the centuriae were organised instead by wealth (and later incorporated some tribal organisation); the tribus were organised by residence.[27]

Development

[edit]The Livian narrative indicates that the first assembly organised on a tribal basis was the plebeian concilium in 471 BC.[28] The tribal assembly – contra concilium plebis, see § Distinction from the plebeian council below, – came into existence some time before 447 BC,[2] when the assembly is first attested as electing quaestors.[29][30] Before the conquest of Veii c. 396 BC there were 21 tribes;[31] the number of tribes reached the classical number of thirty-five in 241 BC. It was not thereafter changed.[32]

The tribal assembly over time came to elect more kinds of magistrates. After the election of quaestors, it started to elect curule aediles in 366 BC, military tribunes in 311, and commissions for the establishment of colonies by 197 BC.[33] Trials before the people (Latin: iudicium populi) were also held before the tribes under the presidency of aediles by 329 and under plebeian tribunes by 212.[34]

Social war

[edit]

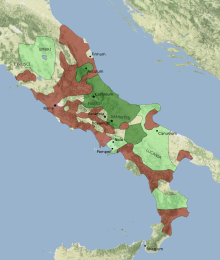

In the aftermath of the Social war (91–87 BC), the Rome's Italian allies received Roman citizenship. How the allies would be incorporated into the Roman citizen body for voting purposes was a highly politicised and difficult question. Various proposals to that effect were brought.

The first was in the lex Julia to give citizenship to the allies.[35] This proposed the creation of a few new tribes – two, eight, or ten – into which the vast numbers of new citizens could be packed and forced to vote last, depriving them of political influence proportionate to their numbers.[36][37] A plebeian tribune of 88 BC named Publius Sulpicius Rufus brought legislation to overturn these arrangements and, passed with force and a political deal with Gaius Marius, enrolled the new citizens in the existing set of thirty-five tribes.[38][39] Although Sulpicius' legislation was abrogated after the then-consul Sulla marched on Rome, his successor Lucius Cornelius Cinna brought and implemented similar legislation in the coming years. By Sulla's return from the east after the First Mithridatic War, re-enrolling the Italians into a few tribes was politically (and militarily) impossible; Sulla and the senate did nothing to disturb it.[40]

Enrolment of the new citizens among the existing tribes made them a target for Roman political electioneering, which relied on the aristocrats plying voters with gifts and patronage.[41] However, the impact of enrolment for the far-flung Italians was minimal since political rights could only be exercised in person at Rome at the initiative of the urban magistrates.[42] Regardless, integrating these new citizens into the urban elite's patronage structures and mobilising them for political struggles at Rome was a fraught and disruptive process which contributed to the stormy politics of the next generation.[43]

Decline

[edit]The tribal assembly is still attested into the imperial era. The last known law passed by any comitia is the lex Cocceia agraria in AD 98.[44][45] It met at least into the third century AD. Memories of the tribes and elections continued into late antiquity, even though the institutions themselves were obsolete.[46]

Apportionment

[edit]While each tribe had each vote and voters were not ranked by wealth for voting purposes, the number of voters within each tribe was not the same. The newer tribes created in the third and fourth centuries likely had within them more voters than the older tribes closer to Rome. Nor was it entirely likely that the outlying tribes' poorer voters would have the time to make themselves physically present in Rome for an assembly. This likely favoured, for rural tribes, wealthy landowners who could afford to make the journey to Rome and have their votes counted.[21] However, this effect may have been mediated in the late republic by population inflows to Rome itself. Since there were no completed censuses between 70 and 28 BC, persons registered in a rural tribe who moved into the city were likely never reassigned to an urban one, meaning that votes were likely dominated by residents of the city.[47]

Each of the tribes was artificial; they did not correspond to any real bond of antecedence but instead to a geographic district in which a voter's properties were.[48] The thirty-five tribes were divided into two groups: the thirty-one "rural" tribes and four "urban" tribes. Initially they were merely differences in residence but by the middle republic the "urban" tribes had become socially inferior.[49] Imperial-era evidence indicates that the urban tribes had some 34 times more citizens at Rome than the rural tribes.[50]

The four urban tribes were assigned to Rome and were Suburana, Palatina, Esquilina, and Collina.[51] Suburana and Esquilina were especially disfavoured.[52] They were perceived as less prestigious: it was a possible punishment from the censors to be relegated from a rural tribe to an urban one.[53] Moreover, so to restrict the influence of manumitted slaves and dilute their individual votes, these were the four tribes into which all freedmen were assigned regardless of their locations of actual residence. While attempts were made at various times to assign freedmen to rural tribes and win their political support, such attempts were always reverted.[54][55]

The other thirty-one rural tribes were, in traditional order – assigned in a counter-clockwise order by geography around Rome – with exception of Aemilia whose place in the order is not known,

- Romilia,

- Voltinia,

- Voturia,

- Horatia,

- Maecia,

- Scaptia,

- Pomptina,

- Oufentina,

- Papiria,

- Teretina,

- Falerna,

- Lemonia,

- Pupinia,

- Poblilia,

- Menenia,

- Aniensis,

- Camilia,

- Claudia,

- Cornelia,

- Velina,

- Quirina,

- Sergia,

- Pollia,

- Clustumina,

- Stellatina,

- Fabia,

- Tromentina,

- Sabatina,

- Galeria, and

- Arnensis.[56]

Each tribe corresponded to a geographic area. Initially, in the archaic period they were expanded largely by extending the neighbouring tribe and attaching whatever the relevant territory contiguously.[57] However, when Rome conquered substantial territories, such as after the victory over Veii, new tribes were established therein.[58] However, they were also sometimes associated with specific ethnic areas, lumped together as a single tribe after conquest. Both poor and rich citizens benefited from new tribes: the poor received land allotments and the rich, by changing tribe, gave themselves political influence in a tribe which, due to distance from Rome, sent few voters but received a same vote regardless.[58]

The continued expansion of formal Roman territory, made it sometimes inconsistent as to which tribe a new town should be assigned. Sometimes, a town could be assigned to an existing tribe on the basis that it was the same radial direction from Rome as the existing tribe.[59] Other times, tribes expanded contiguously but with little attention paid to radial direction, such as along the Tyrrhenian coast.[60] Towns could also be grouped by original ethnicity and enrolled in the same tribe: the land of the ager Gallicus for example was mostly enrolled into the tribe Pollia.[61] Finally, tribes could be assigned arbitrarily, or at least for reasons not now knowable, or for gerrymandering-like political reasons.[62]

By the middle republic, the tribes had become hugely malapportioned, especially so for the huge and distant tribes Pollia and Velina.[63] Further expansion of Roman territory in the aftermath of the Social war and the eventual decision to enrol the Italians into the existing thirty-five tribes rather than confine them to a limited number of new tribes, compounded the chaos. The Latins, who were ancient Roman allies were enfranchised and registered likely based on the tribe previously assigned to their magistrates (since 125 BC magistrates of Latin towns received Roman citizenship and a tribe).[64] Other Latins were assigned to tribes that were known to have few citizens.[65] The Italians who fought against Rome, however, were assigned by ethnicity to tribes that were not allotted to the Latins.[66] By the end of the post-Social war enrolments, the tribes remained malapportioned (though to an extent less so with expansion of some of the smaller tribes) and had also become largely non-contiguous, with some tribes divided into up to six different districts.[67]

In the late republic the older rural tribes close by to Rome may have become depopulated by urban inflow and the yeoman decline. Such tribes would have become akin to rotten boroughs where aristocratic families controlled tribal votes malapportioned to a tiny electorate.[21] However, it is not clear whether rural tribesmen migrating to Rome were routinely re-enrolled into the urban tribes. That after the Sullan period the censors were never able to complete their tasks suggests that no such re-enrolment occurred.[47]

Distinction from the plebeian council

[edit]The tribal assembly and the plebeian council were organised on the same principles and voted by tribes. After the lex Hortensia in 287 BC endowed the plebeian council with full legislative powers, the two assemblies became practically identical.[1] The modern orthodoxy distinguishes a comitia tributa from a concilium plebis, where the latter is a meeting of plebeians alone. Under this formulation, there are two tribal assemblies, one of the whole people and one of plebeians only.[68]

Some scholars believe that there was, however, only one tribal assembly. In this formulation, the only tribal assembly was the plebeian council and that for most, if not all, of the republican era tribal assemblies were convened by plebeian tribunes and not by curule magistrates such as consuls and praetors. Under this view, the statements that a consul or praetor legislated before the tribes were simplifications meant to express a curule magistrate leaning on a friendly tribune.[69] This view rejects the modern "orthodoxy"[70] from Theodor Mommsen that the separation reflected plebeians' status as a "state within a state"[71][72] and accentuates the difference between tribal and centuriate assemblies, placing the former as the people organised for a civil purpose (domi) within the pomerium and the latter as organised for a military one (militiae) on the campus Martius outside that sacral boundary.[73]

Andrew Lintott, in Constitution of the Roman Republic (1999), rejects the single tribal assembly hypothesis, noting that in the historical period there are multiple cases where laws were brought before the tribes by curule magistrates.[74] Belief in an early weak comitia tributa may have emerged during Sulla's consulship when he brought legislation – appealing to an invented Servian tradition – to make the comitia centuriata the sole legislative assembly.[75]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Lomas 2018, p. 189.

- ^ a b c Momigliano & Cornell 2012.

- ^ Cornell 2022, pp. 226–27, noting also that by the middle republic the distinction between tribal assembly and plebeian council was "mere technicality".

- ^ Sandberg 2018, noting that "in later republican times, most legislative assemblies were tribal ones, convened by tribunes of the plebs".

- ^ Lomas 2018, p. 297; Lintott 1999, p. 40.

- ^ Lomas 2018, p. 297.

- ^ Cornell 2022, p. 227, citing Cic. Amic., 96; Varro Rust., 1.2.9.

- ^ Vishnia 2012, p. 133, noting that Gaius Licinius Crassus was responsible for moving from the comitium to the forum.

- ^ Lomas 2018, p. 234, noting maximum capacity.

- ^ Mouritsen 2017, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Lintott 1999, p. 55, noting a terminus post quem with Tiberius Gracchus' tribunate in 133 BC.

- ^ Vishnia 2012, p. 134.

- ^ Vishnia 2012, p. 129.

- ^ Tatum 2009, p. 221.

- ^ Vishnia 2012, p. 129, noting introduction of secret ballot for elections in 139, for non-treason trials in 137, for legislation in 131 or 130, and for treason trials in 107.

- ^ Vishnia 2012, p. 121.

- ^ a b c Mouritsen 2017, p. 50.

- ^ Vishnia 2012, pp. 97, 121.

- ^ The principium as omen: Cornell 2022, p. 227. Rejecting the principium as omen: Mouritsen 2017, p. 50.

- ^ Cornell 2022, p. 227, asserting the order was determined by lot.

- ^ a b c Cornell 2022, p. 227.

- ^ a b Vishnia 2012, p. 122.

- ^ Vishnia 2012, pp. 122, 123.

- ^ Mouritsen 2017, p. 56; Vishnia 2012, p. 128. Both cite Cicero, Pro Sestio, 109

- ^ Vishnia 2012, p. 126, noting figures provided by Mouritsen at 0.66% and Nicolet at 1.85%.

- ^ Lomas 2018, p. 136; Cornell 1995, p. 25.

- ^ Cornell 1995, p. 116.

- ^ Momigliano & Cornell 2012, citing Livy, 2.56.2.

- ^ Pina & Díaz 2019, p. 196, citing Tac. Ann., 11.22.

- ^ Badian & Honoré 2012.

- ^ Lomas 2018, p. 188.

- ^ Tan 2023, p. 110; Forsythe 2005, p. 179.

- ^ Stewart 2012, noting that the election of colonial administrations may be documented as early as 296 or 467 BC as well.

- ^ Stewart 2012, citing: Livy, 8.22.3, 25.3; Valerius Maximus, 8.1.7.

- ^ Gabba 1994, p. 123.

- ^ Mouritsen 1998, p. 163, adding in n. 32, that the number of new tribes is unclear: "Sisenna, 17P, mentions an early proposal to create two new tribes, while Velleius, 2.20.2, states that the new citizens were to be inscribed in eight [new] tribes".

- ^ Steel 2013, p. 86 n. 25, citing Appian, Bella civilia, 1.49, for ten new tribes.

- ^ Seager 1994, pp. 167–68 (distribution among the tribes, Marius' support), 169–71 (Sulla's response); Mouritsen 1998, pp. 168, 171, noting Sulpicius brought legislation to distribute the freedmen among the rural tribes as well, citing Livy, Periochae, 77.

- ^ Broughton 1952, p. 41, citing: Asc., 64C; Appian, Bella civilia, 1.55–56; Livy, Periochae, 77.

- ^ Mouritsen 1998, p. 168.

- ^ Mouritsen 1998, p. 170.

- ^ Mouritsen 1998, pp. 169–70.

- ^ Mouritsen 1998, p. 171.

- ^ Momigliano & Cornell 2012; Stewart 2012.

- ^ Bujuklic, Zika (1999). "Ancient and modern concepts of lawfulness". Revue internationale des droits de l'antiquité. 46: 123–64. See p. 154 n. 69, citing Dig., 47.21.3.1 (Callistratus).

- ^ Millar 1998, pp. 198–99.

- ^ a b Cornell 2022, p. 228.

- ^ Cornell 2022, p. 227, noting that the urban elite voted based on the location of their country estates while the landless urban poor voted in the urban tribes.

- ^ Lomas 2018, p. 293.

- ^ Taylor & Linderski 2013, p. 149.

- ^ Taylor & Linderski 2013, p. 70, attributing the order to Varro and Festus.

- ^ Taylor & Linderski 2013, p. 148.

- ^ Taylor & Linderski 2013, p. 138.

- ^ Taylor & Linderski 2013, pp. 132–33.

- ^ Lomas 2018, pp. 293–94, noting reform attempts to enrol freedmen in the rural tribes and revise the senate rolls by Appius Claudius Caecus then-censor in 308 BC that were quickly reverted and unsuccessful, respectively.

- ^ Taylor & Linderski 2013, p. 74.

- ^ Taylor & Linderski 2013, p. 41.

- ^ a b Taylor & Linderski 2013, p. 48.

- ^ Taylor & Linderski 2013, pp. 86–87, noting this stopped due to infeasibility by the second century BC.

- ^ Taylor & Linderski 2013, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Taylor & Linderski 2013, pp. 90–91, noting also that Pollia became one of the largest tribes due to continued expansion into formerly Gallic land.

- ^ Taylor & Linderski 2013, pp. 91–93.

- ^ Taylor & Linderski 2013, p. 99.

- ^ Taylor & Linderski 2013, pp. 108–10.

- ^ Taylor & Linderski 2013, p. 111.

- ^ Taylor & Linderski 2013, p. 114.

- ^ Taylor & Linderski 2013, pp. 116–17, noting that Romilia, Pupinia, and Sabatina remained relatively small and over-weighted.

- ^ Lintott 1999, p. 53.

- ^ Lintott 1999, p. 53; Forsythe 2005, pp. 180–81, citing Livy, 2.56.2 referring to a tribal electoral comitia for plebeian officials termed comitia tributa.

- ^ Lintott 1999, p. 53 n. 62.

- ^ Forsythe 2005, pp. 176, 180.

- ^ But see Cornell 1995, p. 265.

- ^ Forsythe 2005, p. 181.

- ^ Lintott 1999, pp. 53–54, noting the lex Quinctia in 9 BC, the lex Gabinia Calpurnia de Delo in 58, a lex Cornelia during Sulla's dictatorship, and an epigraphic law attributed directly to a praetor.

- ^ Forsythe 2005, p. 233.

Bibliography

[edit]Modern sources

[edit]- Broughton, Thomas Robert Shannon (1952). The magistrates of the Roman republic. Vol. 2. New York: American Philological Association.

- Crook, John; et al., eds. (1994). The last age of the Roman Republic, 146–43 BC. Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 9 (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-85073-8. OCLC 121060.

- Gabba, E. "Rome and Italy: the Social War". In CAH2 9 (1994), pp. 104–28.

- Seager, R. "Sulla". In CAH2 9 (1994), pp. 165–207.

- Cornell, Tim (1995). The beginnings of Rome. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-01596-0. OCLC 31515793.

- Cornell, Tim C (2022). "Roman political assemblies". In Arena, Valentina; Prag, Jonathan (eds.). Companion to the political culture of the Roman republic. Wiley Blackwell. pp. 220–35. ISBN 978-1-119-67365-1. LCCN 2021024437.

- Forsythe, Gary (2005). A critical history of early Rome. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-94029-1. OCLC 70728478.

- Hornblower, Simon; et al., eds. (2012). The Oxford classical dictionary (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-954556-8. OCLC 959667246.

- Badian, Ernst; Honoré, Tony. "quaestor". In OCD4 (2012). doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.5470

- Momigliano, Arnaldo; Cornell, Tim. "comitia". In OCD4 (2012). doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.1747

- Lomas, Kathryn (2018). The rise of Rome. History of the Ancient World. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. doi:10.4159/9780674919938. ISBN 978-0-674-65965-0. S2CID 239349186.

- Millar, Fergus (1998). The crowd in Rome in the late republic. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-10892-1.

- Mouritsen, Henrik (1998). Italian unification. London: British Institute of Classical Studies. ISBN 0-900587-81-4.

- Mouritsen, Henrik (2017). Politics in the Roman republic. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-03188-3. LCCN 2016047823.

- Lintott, Andrew (1999). Constitution of the Roman republic. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926108-6. Reprinted 2009.

- Pina Polo, Francisco; Díaz Fernández, Alejandro (23 September 2019). The Quaestorship in the Roman Republic. KLIO / Beihefte. Neue Folge. De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110666410. ISBN 978-3-11-066641-0. S2CID 203212723.

- Sandberg, Kaj (31 December 2018). "Comitia and concilia". The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah20037.pub2.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - Steel, Catherine (2013). The end of the Roman republic, 149 to 44 BC: conquest and crisis. Edinburgh History of Ancient Rome. Edinburgh University Press. doi:10.1515/9780748629022. ISBN 978-0-7486-1944-3.

- Stewart, Roberta (26 October 2012). "Tribus". The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. Wiley. doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah20132.

- Tan, James (2023). "Geography and the reform of the comitia centuriata". Classical Quarterly. 73 (1): 109–126. doi:10.1017/S0009838823000484. ISSN 0009-8388.

- Tatum, W Jeffrey (2009). "Roman democracy?". In Balot, Ryan K (ed.). A companion to Greek and Roman political thought. Wiley. pp. 214–27. doi:10.1002/9781444310344. ISBN 978-1-4051-5143-6.

- Taylor, L R; Linderski, Jerzy (2013) [First ed. published 1960]. The voting districts of the Roman republic: the thirty-five urban and rural tribes (Updated ed.). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-11869-4. OCLC 793581620.

- Vishnia, Rachel Feig (2012). Roman elections in the age of Cicero: society, government, and voting. Routledge Studies in Ancient History. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-87969-9.

Ancient sources

[edit]- Appian (1913) [2nd century AD]. Civil Wars. Loeb Classical Library. Translated by White, Horace. Cambridge – via LacusCurtius.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Cicero. De legibus.

- Cicero. De re publica.

- Cicero. Pro Sestio.

- Livy (1905) [1st century AD]. . Translated by Roberts, Canon – via Wikisource.

- Livy (2003). Periochae. Translated by Lendering, Jona – via Livius.org.

- Valerius Maximus. Factorum et dictorum memorabilium.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

External links

[edit]- Devereaux, Bret (21 July 2023). "How to Roman Republic 101, Part I: SPQR". A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry. Retrieved 27 November 2023.