Top-four primary

| A joint Politics and Economics series |

| Social choice and electoral systems |

|---|

|

|

|

This article or section appears to contradict itself on the invention of the top-four system. (August 2024) |

A final-four or final-five primary is an electoral system using a nonpartisan primary by multi-winner plurality in the first step.[1][2]

The Final-Four Voting system was first proposed by businessmen Katherine Gehl and Michael Porter in a 2017 report entitled "Why Competition in the Politics Industry is Failing America".[3] It was first advocated by FairVote in 2012.[4][5] FairVote proposed a statutory model in 2015.[6]

It was first used in the 2022 Alaska special election.

A top-four primary can be seen as a variation of a two-round system, in which the second round (general election) is always held, even if a candidate gains a majority in the first (primary) round. A candidate receiving 20% of the primary vote is logically guaranteed to pass a top-four primary.[7] One variation, called Final Five Voting, allows five candidates to pass the open primary.[8]

Usage

[edit]Top-four

[edit]Alaska

[edit]

The 2020 Alaska Measure 2 initiative in Alaska for top-four primary narrowly passed with 50.55% of the vote.[1] It will be used for all state and federal elections except presidential elections.

The Alaskan Independence Party sued, declaring Ballot Measure 2 as unconstitutional. On January 19, 2022, the Alaska Supreme Court ruled that the measure was constitutional.[9]

The nonpartisan primary is held using first past the post, with voters allowed one vote, and the four candidates with the most votes advancing to the general. The general election ballot allows candidates to be ranked, using Instant-runoff voting elimination to identify a majority winner. The first top-four primary election occurred on August 16, 2022.[10]

For Alaska's 2022 at-large congressional district special election, 48 candidates registered. Nine candidates were invited to a first panel discussion organized as an industry forum: 5 Republicans, 2 Democrats and 2 independents, based on various criteria.[11] Although there were 48 candidates, the top-4 candidates gained 68.8% of the vote in the June special election primary: Sarah Palin 27.01%, Nick Begich III 19.12%, Al Gross 12.63%, and Mary Peltola 10.08%. The 5th-finishing candidate, Tara Sweeney, had 5.92%.

Al Gross withdrew after the primary, and suggested that 5th-place Sweeney should be included in the final ballot, but this was not allowed.[12][13]

In the first round of the general election, Republican votes were split between first-rank preferences for Palin and Begich, creating a spoiler effect known as a center squeeze.[14][15][16] Begich was eliminated first.[17][18][19][20] In the instant runoff, Begich voters split their second choices between Palin and Peltola, and Peltola won. Despite Begich's greater overall popularity, Palin's second-choice votes were not allowed to transfer to Begich (which would have allowed Begich to win the election).

The highest-profile election held under the new system has been the 2022 U.S. Senate election in Alaska. Moderate Lisa Murkowski was reelected after not having to win a Republican primary that she narrowly lost twelve years earlier.[21]

In 2024, Alaskans narrowly voted down a measure to repeal the system and return to partisan primaries.[22] 50.11% voted to keep the system.

Missouri

[edit]The Better Elections campaign of Missouri collected 300,000 signature for a Top-Four Ranked-Choice Voting for local, state, and Federal Officials, needing 160,199 valid signatures. The initiative would have been voted on in November 2022.[23][24][2] But the legislature required the signatures to be distributed among six congressional districts to qualify, and the campaign did not collect enough in Missouri's 1st District. The initiative was rejected.[25][26] The ballot initiative will be attempted again.[27]

Top-five

[edit]Petitions sponsored by Katherine M. Gehl and Institute for Political Innovation.

Nevada

[edit]After a petition by Nevada Voters First for a Top-Five Ranked-Choice Voting Initiative received the minimum number of signatures, the proposal appeared on the ballot in November 2022.[28]

The initiative proposed to amend the Nevada Constitution to establish open top-five primaries and instant-runoff voting for general elections. It would allow the 35% of voters who are not registered to a party to influence the candidates who advance to the general election. The change would apply to congressional, gubernatorial, state executive offices, and state legislative elections. Implementing legislation would need to be adopted by July 1, 2025.[29]

It was narrowly approved by voters in 2022, and needed to be approved again in 2024 to take effect.[30] It was narrowly rejected.

Benefits

[edit]- More choices for voters while protecting majority rule

- A traditional top-two blanket primary often reduces the field too far, eliminating strong candidates who otherwise deserve attention in the debates and general election.

- Not too many choices

- Limiting the general election to four candidates helps focus attention to a small set of candidates. In round two (general election) voters only need to rank 3 choices to be able to express a preference between the final two candidates in identifying a majority winner.

- In contrast, some municipal elections use instant-runoff voting (IRV) with a single round of voting, remove the primary to save money and give voters more choice in the higher turnout general election[31] however this risks a general election with dozens of candidates, making it harder for voters to know which candidates can win, and which candidates need to be ranked to express a vote among the final two.

- All voters help decide who advances

- Replacing a closed partisan primary with a blanket primary can help protect a moderate strong incumbent from being knocked out in a closed party primary by a more extreme candidate within that party. An incumbent only needs to make top-four to advance.[32]

- Any challenger to an incumbent, even within the same party, can advance if they also are able to make the top-four.

Drawbacks

[edit]Vote splitting

[edit]Primary

[edit]With a pick-one, top-four primary, advancing top-four candidates maintains a threat of vote splitting, though to a lesser degree than a pick-one nonpartisan blanket primary top-two primary. There may be multiple candidates eliminated below fourth place, while some could have advanced if fewer candidates had run and split their vote. For illustration, a party with 48% could theoretically win all top-four if their four candidates each earned 12%, while a stronger 52% majority party might equally split their votes at 10.4% each and lose all five candidates. Vote-splitting will be experienced as threatening to parties who may lose all their candidates, compared to a closed primary where one candidate from each party always advances. To avoid vote-splitting for the general election, parties must still try to discourage too many candidates running under their label, and party voters need to be informed which candidates are most likely to advance to avoid wasting their vote. The use of sequential-elimination ranked IRV in the primary can lessen the effects of vote splitting.

General

[edit]Vote splitting can also be an issue in the ranked-choice voting general election.[33][34][35][36][14][15][16] Candidates are eliminated based only on first-choice votes, which become split between similar candidates vying for them. The transfer of votes between candidates can mitigate this effect somewhat (if two candidates have identical appeal to voters and their votes largely transfer to each other) but does not eliminate it in the general case, as advocates claim.[37][38] Multiple candidates from the same party can split the vote due to vote exhaustion, where voters do not rank all candidates on a ballot. This can result in the winner of the election being elected by a minority of voters.[39]

In the 2024 United States House of Representatives election in Alaska, a super PAC linked to the Democratic Party spent money to elevate three Republican candidates into the general election. Politico stated it would be easier for the Democratic incumbent, Mary Peltola to win "if three Republicans are splitting the GOP vote".[40]

Voter deception

[edit]Lawyer Kenneth Jacobus, who filed an unsuccessful 2021 lawsuit against Alaska's top-four primary, argued that because political parties cannot nominate candidates, the system violates parties' freedom of association and makes it easier for candidates to deceive voters. For example, a left-wing candidate could run under the Republican Party label in order to get votes. Alaska Assistant Attorney General Margaret Paton-Walsh argued in response that political parties could still influence the election by endorsing and providing support for candidates.[41]

Variations

[edit]The uniting feature of all variations is to reduce the field of candidates in a primary round, and confirming a majority winner in the general election. Ranked ballots enables a majority winner among more than two candidates.

Final Five Voting

[edit]- Final-Five Voting is a voting system that combines a single ballot primary that includes candidates of all parties in an instant runoff style general election. The Final-Five Voting concept was originated by Katherine Gehl and Michael Porter in their book, The Politics Industry: How Political Innovation Can Break Partisan Gridlock and Save Our Democracy (2020).[42]

- Allowing five candidates to advance could, for example, allow two strong Democrats, two strong Republicans and one independent to advance, allowing intra-party and inter-party differences of opinion to be debated.[8][43][44] However, Final Five Voting is still vulnerable to vote-splitting, which could cause it to advance candidates all from the same party, even if the majority of voters preferred a different party.

Primary

[edit]| Pick-one | Ranked-choice | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple | With floor threshold | Sequential elimination | With floor and consolidation thresholds |

|

|

|

|

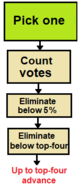

- Pick-One, Top-Four Advance

- The simplest voting top-four primary uses pick-one, allowing only one choice to be expressed, and the top-four candidates advance, first proposed by FairVote in 2012[4] for giving twice as many choices as a traditional top-two primary. The eventual winner of any runoff system will likely be in this top-four set, but in a primary of many candidates, there will be vote-splitting and like-minded voters are not allowed the chance to consolidate behind a strongest choice.

- A lower threshold may be included to eliminate candidates below it. This may allow fewer than four candidates to advance and focus attention on the strongest candidates in the general election.

- Use IRV Sequential-Elimination for Top-Four

- Using ranked ballots and IRV in the open primary is not necessary, but it minimizes the risks of vote splitting where a party might lose all their candidates. A IRV sequential-elimination process will maximize the number of voters helping to pick the top set of candidates who advance.

- With sequential-elimination, a party (or any group) with 20% of the vote, with members ranking only within their party, they will be guaranteed to advance at least one strongest candidate.[45]

- Minimum Thresholds in Top-Four

- Minimum thresholds may be required to pass the primary. There are two types of threshold - a lower floor threshold on the first count with first-rank support, and a higher consolidation threshold with elimination of lower candidates. Thresholds are often used in exhaustive ballot runoffs if candidates don't voluntarily withdraw.[46] In a top-four process, there is an implicit threshold of 20% above which a candidate is logically guaranteed to make the top-four.

- A 5% floor threshold may be required for first choice viability, and a 10% consolidation threshold with transfer votes from a sequential-elimination. Including thresholds may result in fewer than four candidates advancing, rewarding stronger candidates with more attention.

- For example, if four candidates remaining have A=48%, B=45%, C=5%, and D=2% of the vote, it can be argued it is better to also eliminate C and D, allowing voter attention to focus on the strongest two candidates.

- Lower-end thresholds, like a 1% floor threshold and 5% consolidation threshold can still be useful over no thresholds as a vetting process.

- Threshold passed helps vet candidates as serious and deserving of journalistic attention, debate/forum inclusion, and general election ballot access. These significant weaker candidates may be unable to win, but they can help change the quality of campaign issues that are addressed. Stronger candidates have an incentive to pick sides on the issues of weaker candidates to earn lower rank support from their voters.

An argument in favor of a pick-one top-four primary is that people's first rank choices are most important and the eventual winner of the election will most likely be among the top-four first-rank choices. A pick-one top-four primary can be considered a single non-transferable vote (SNTV) system. An argument in favor of using IRV sequential-elimination in the primary is that more voters help pick the top-four, and marginally more will be happy with supporting at least one in the general election.[clarification needed]

Post-primary

[edit]- Voluntary Drop-out Between Primary and General

- If a party advances two (or more) candidates among the top-four, candidates may desire to drop out and endorse another, helping a party focus resources and earn more positive attention on that one strongest choice. To aid this process, election rules may include a final date for candidates to drop-out and be voluntarily excluded from the general election ballot. That final date would ideally be after a public debate/forum, along with feedback from public polls.

| Sequential | Top-two |

|---|---|

|

|

General

[edit]- Sequential-Elimination IRV in General election

- An instant-runoff voting general election eliminates one candidate at a time, allowing ballots for eliminated candidates to move to their next viable choice. This process continues until one candidate consolidates a 50%+1 of the vote.[5]

- Top-two Advancement or Batch-style Elimination IRV in General election

- A top-two IRV advancement may be preferable for major parties or candidates, allowing the top-two candidates to advance to compete head-to-head in a final count. A top-two IRV or batch-style IRV elimination was used in 3 states in 1912: Florida, Indiana, and Minnesota (called preferential voting, replaced by party primaries by the 1930s).[47][48]

- Top-two IRV makes no difference among three candidates, but among four, a top-two may cause vote-splitting between third and fourth place: they could both be eliminated without a chance to consolidate. This risk of vote splitting can encourage one of two like-minded candidates to drop out, if both are polling below top-two.

- Top-two IRV is consistent with majority rule among four candidates. The top-two candidates control the largest pair-combined majority of the vote. Candidates who believe they can win don't want to risk falling from second place to third and lose their chance to compete head-to-head against their strongest rival.

- For example, a tough top-four election case might look like: A=40%, B=25.01%, C=24.99%, D=10%. A sequential-elimination IRV would eliminate D and allow their transfer votes to decide which of B or C advances, while the top-two IRV process would let A and B compete head-to-head for a winner. The system has no knowledge which of A, B, or C can win a final majority, so it can be argued most fair to reward the voters of B with the chance to compete head-to-head against A for having more top-choice support. This potential vote splitting can be considered to punish D voters, those who support C next, for not compromising immediately to a stronger choice. However supporters for C and D both retain a chance to help identify the majority preference between A and B via their lower ranked choices.

- Condorcet Methods or Round Robin Voting in General election

- Edward B. Foley, American lawyer, law professor, election law scholar, promotes a Round-robin voting[49] process (Like Round-robin tournaments) in a top-four general election.[50] This identifies a head-to-head Condorcet winner, using ranked ballots to determine all 6 permutations pairwise majority preferences among 4 candidates (A versus B, A v. C, A v. D, B v. C, B v. D, C v. D). If one candidate can beat the other 3 pairwise, they win as the strongest majority candidate.

- Condorcet elections differ from runoff elections in that all lower preferences are considered, and how a voter ranks lower preferences can affect whether higher choices win or lose. This fact may encourage tactics such as bullet voting for a favorite or burying strongest rivals. (In contrast IRV meets a Later-no-harm criterion which promises to never let lower choices harm higher ones, because they are ignored unless all higher ones are eliminated, but it does not make it safe to rank a favorite first.)

- This can cause surprising results. Theoretically a choice who is no one's first choice can win, for being everyone's second choice. (IRV, in contrast, can eliminate a candidate even when the electorate preferred them over all others.)

- It is also possible there will be no Condorcet winner. For instance, in the Rock, Paper, Scissors game each choice beats one, and loses to one. These circular ties are rare, but in such cases, special rules must be decided to break the "cycle" to pick a winner.

- For example, the Black method uses the Borda count instead if there is a cycle (named after Duncan Black). Better special rules ideally would attempt to minimize the benefits of insincere tactical voting.

Summary

[edit]All of these variations, including a traditional nonpartisan blanket primary, allow a majority to confirm the winner.

- A top-four primary allows twice as many choices in the general election as a top-two.

- A sequential-elimination IRV process in the primary is important because the primary is best designed to help like-minded voters consolidate to their strongest collective choice.

- Including a floor threshold (like 5%) with batch-elimination and consolidation threshold (like 10%) with sequential-elimination in the primary will help advance only the strongest candidates, which may be less than four.

- A top-two IRV process in the general election may be preferred because the consolidation process is complete and voters for the top-two first-rank candidates will feel they have earned the right to compete head-to-head.

- A Round Robin Voting or Condorcet process in the general election may be preferred because it more deeply reflects voters will by using all ranked preferences, rather than just top ones.

| # | Round one (primary) | Round two (general) | Implementations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pick-one, top-two advance | Pick-one | Traditional nonpartisan blanket primary | |

| 1 | Pick-one, top-four advance | Top-two IRV | |

| 2 | Pick-one, top-four advance | Ranked IRV, sequential-elimination | Alaska[9] |

| 3 | Ranked-choice, sequential-elimination until at most four remain | Ranked IRV, sequential-elimination | |

| 4 | Ranked-choice, sequential-elimination until at most four remain | Top-two IRV | |

| 5 | (Any top-four process) | Round-robin voting |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Alaska Voters Approve Landmark Nonpartisan Election Reforms". 18 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Missouri Top-Four Ranked Choice Voting Elections for Local, State, and Federal Officials Initiative (2022)".

- ^ Gehl & Porter (September 2017). "Why Competition In The Politics Industry Is Failing America" (PDF). Harvard Business School. Retrieved May 7, 2024.

- ^ a b Fixing Top Two in California The 2012 Elections and a Prescription for Further Reform

- ^ a b Top Four FairVote August 2013

- ^ "FAIRVOTE'S 2015 POLICY GUIDE: MODEL STATUTORY LANGUAGE".

- ^ Top Four Why Top Four Gives More Voice to Voters (FairVote)

- ^ a b "Final-Five Voting".

- ^ a b "Alaska Ballot Measure 2, Top-Four Ranked-Choice Voting and Campaign Finance Laws Initiative (2020)".

- ^ "Alaska Division of Elections".

- ^ "Alaska U.S. House candidates use industry forum to try to stand out in crowded field". 13 May 2022.

- ^ "Independent al Gross says he's ending Alaska House bid".

- ^ "Alaska judge sides with elections office in decision keeping Tara Sweeney off U.S. House special election ballot".

- ^ a b Samuels, Iris (October 11, 2022). "Republican U.S. House candidates in Alaska continue to attack each other while urging voters to 'rank the red'". Anchorage Daily News. Retrieved 2022-10-15.

Begich and Palin … split the Republican share of the vote in an August special election, allowing Peltola to come away with the victory

- ^ a b Derysh, Igor (2022-09-01). ""Scam to rig elections": Tom Cotton fumes over Sarah Palin loss as GOP fans cry "stolen election"". Salon. Retrieved 2022-10-15.

Peltola would have still won under traditional rules because she finished first while the two Republicans split the GOP vote share.

- ^ a b "Trump-backed Sarah Palin loses special election for Alaska congressional seat". World Socialist Web Site. 2 September 2022. Retrieved 2022-10-15.

the Republican vote was split nearly equally between Palin and Nick Begich

- ^ Graham-Squire, Adam; McCune, David (2022-09-18). "A Mathematical Analysis of the 2022 Alaska Special Election for US House". arXiv:2209.04764 [econ.GN].

Begich wins both of his head-to-head matchups against the other two candidates

- ^ "Did the 2022 Alaska congressional special election have a Condorcet winner?". Politics Stack Exchange. Retrieved 2022-10-15.

- ^ "It's official: Sarah Palin cost the GOP a House seat". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2022-10-15.

the other Republican in the race, Nick Begich, would have defeated Rep.-elect Mary Peltola (D) if the race had boiled down to the two of them.

- ^ Montalbano, Sarah. "Alaska's Ranked-Choice Voting Was a Fiasco. Nevada Should Take Note". The American Spectator. Retrieved 2022-10-15.

Palin and Begich split the Republican first-choice votes with 31.3 percent and 28.5 percent respectively … The FairVote analysis reveals that in any scenario except the one that played out, Begich would have won.

- ^ https://apnews.com/article/2022-midterm-elections-donald-trump-alaska-223ea5a590c1b9c4f7905ab4b7849e6f

- ^ Kitchenman, Andrew (2024-11-20). "Alaska chooses to keep ranked choice voting, Begich defeats Peltola, unofficial results show". Alaska Beacon. Retrieved 2024-12-11.

- ^ "Campaigns for ranked-choice voting ballot initiatives in Missouri, Nevada have raised millions ahead of signature deadlines – Ballotpedia News". 20 April 2022.

- ^ "Signatures submitted for ranked-choice voting initiative in Missouri – Ballotpedia News". 10 May 2022.

- ^ Keller, Rudi (2022-07-18). "Fate of Missouri marijuana initiative petition unclear as signature count continues". Missouri Independent. Retrieved 2023-01-31.

Better Elections did not have sufficient signatures in the 1st District, where tabulation is complete.

- ^ Ashcroft, John R. "Constitutional Amendment to Article VIII, Relating to Elections for State and Federal Officials, version 1 2022-051" (PDF).

- ^ Keller, Rudi (2022-06-16). "Ranked-choice voting proposal may miss Missouri ballot, campaign says". Missouri Independent. Retrieved 2023-01-31.

- ^ "Supreme Court: Ranked-choice voting can go to ballot, but not tax petitions, vouchers". 28 June 2022.

- ^ "Nevada Top-Five Ranked Choice Voting Initiative (2022)".

- ^ "Indy Explains: Nevada passed the ranked-choice voting, open primary ballot question. What happens next?". The Nevada Independent. 2022-11-25. Retrieved 2024-06-01.

- ^ "2020's Elections Show Cities and States Leading on Democracy Reform". 4 November 2020.

- ^ "Will Ranked-Choice Voting Help or Hurt Lisa Murkowski?". 30 June 2021.

- ^ Maskin, Eric (2022-06-17). "How to Improve Ranked-Choice Voting and Democracy". Capitalism and Society. Rochester, NY: 3. SSRN 4138767.

- ^ Poundstone, William (2013). Gaming the vote : why elections aren't fair (and what we can do about it). New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 180. ISBN 978-1-4299-5764-9. OCLC 872601019.

IRV is subject to something called the "center squeeze." A popular moderate can receive relatively few first-place votes through no fault of her own but because of vote splitting from candidates to the right and left.

- ^ "Rebutting false and misleading testimony from RCV advocates". Oregon State Legislature. 2022.

RCV does not eliminate spoilers or vote-splitting, and studies show that they can occur in 1 in 5 competitive elections

- ^ Hamlin, Aaron (2019-02-07). "The Limits of Ranked-Choice Voting". The Center for Election Science. Retrieved 2022-10-15.

On the surface, with all the ranking transfers that RCV does, it looks like RCV addresses the vote splitting issue. But it only does so a little bit.

- ^ McGuire, Brendan (2020-12-31). "The Top-Four Primary and Alaska Ballot Measure 2". Alaska Law Review. 37 (2): 311. ISSN 0883-0568.

There are four core arguments in favor of top-four primary systems: … (d) avoid "vote splitting."

- ^ Brittingham, Audrey (2021-06-10). "Ranked Choice Voting: How Voters Have Responded to a Failing Political System". Indiana Journal of Law and Social Equality. 9 (2): 262.

It eliminates "vote splitting" or the idea of "throwing your vote away" in order to vote your conscience.

- ^ Sbano, Angela (2021-03-02). ""How Should Alaskans Choose?: The Debate Over Ranked Choice Voting"". Alaska Law Review. 37 (2): 304. Retrieved 2024-07-26.

- ^ Mutnick, Ally (2024-08-06). "Dem-linked super PAC elevates Republicans ahead of Alaska primary". POLITICO. Retrieved 2024-08-13.

- ^ Ruskin, Liz (2021-07-13). "This lawsuit stands between Alaskans and a new ranked choice election system". KTOO. Retrieved 2024-07-26.

- ^ Santucci, Jack (March 25, 2021). "Wiley Online Library". Governance. 34 (2): 596–599. doi:10.1111/gove.12587. Retrieved May 7, 2024.

- ^ "Opinion: It's time to get rid of party primaries". CNN. 12 March 2021.

- ^ "'Final Five' bill would drastically alter how Wisconsin sends people to Congress". 14 December 2021.

- ^ Top Four Primary Ranked Choice Voting for U.S. House Elections

- ^ DFL Call 2008/2009 Archived 2008-02-21 at the Wayback Machine Page 27: VIII. Endorsement for U.S. Senate: 22. General Endorsement Rules: Dropoff rule: Candidates receiving less than 5% will be dropped after the first ballot. On subsequent ballots, the dropoff threshold will be raised by 5% each ballot to a maximum of 25%. After the fifth ballot and each subsequent ballot, the lowest remaining candidates will be dropped so that no more than two candidates remain. In the event that application of the dropoff rule would eliminate all but one candidate, then the two candidates who received the highest percent of the vote on the prior ballot shall be the remaining candidates.

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20120211230909/http://archive.fairvote.org/irv/vt_lite/history.htm In the United States, IRV election laws were first adopted in 1912. Four states -- Florida, Indiana, Maryland, and Minnesota -- used versions of IRV for party primaries. Of the four states with IRV, only the Maryland law used the standard IRV sequential elimination of bottom candidates, while the others used batch elimination of all but the top two candidates.

- ^ Hoag, Clarence Gilbert (1914). Effective Voting: An Article on Preferential Voting and Proportional Representation. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ^ "The Constitution and Condorcet: Democracy Protection through Electoral Reform" Edward B. Foley, Drake Law Review, forthcoming, June 3, 2022 (pp. 10-11, Round-Robin Voting)

- ^ Foley, Edward B. (3 June 2022). "The Constitution and Condorcet: Democracy Protection through Electoral Reform". doi:10.2139/ssrn.4127560. SSRN 4127560.

External links

[edit]- Gustafson, Zane (2020-12-28). "A Top-Four Primary Would Give Voters More Choices". Sightline Institute. Retrieved 2021-03-31.