Tongu do dia toinges mo thúath

Tongu do dia toinges mo thúath is an Old Irish oath which translates to "I swear by the god by whom my people (túath) swear". It is common in early Irish literature, and especially the heroic sagas, where characters swear it in declaring they will perform some feat.

This phrase has been variously interpreted as a relic of Irish paganism, a scholarly Christian invention, and the descendent of a proto-Indo-European formula. The aspect of taboo in this oath has also been discussed.

Tongu do dia in early Irish literature

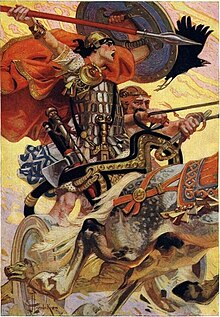

[edit]In early Irish literature, and especially in the prose epics, characters are frequently made to swear formulaic oaths. These oaths functions as asseverations, preceding declarations that the character will perform some action or fulfil some threat. Cú Chulainn is frequently made to swear such oaths in the epic Táin Bó Cúailnge.[1][2] For example, in the earliest recension of the Tain, when told that to kill Fóill, son of Nechtain Scéne, he must kill him with the first blow, he says the following:

tongu do dia toinges mo thúath, nocon imbéra-som for Ultu a cles sin dorísse diano tárle mánaís mo phoba Conchobair as mo láim-sea

I swear by the god by whom my people swear, he shall not play that trick again on Ulstermen, if once the broad spear of my master Conchobar reach him from my hand.[1]

The oath in this passage, tongu do dia toinges mo thúath ("I swear by the god by whom my people swear"), is a very common one in early Irish literature.[2] The oath appears in several forms. Ruairí Ó hUiginn has listed 25 variants. Among the commonest are tongu do dia toinges mo thúath, tongu a toinges mo thiath immurgu ("I swear indeed by what my people swear") and tongu do dia a tonges mo thiath ("I swear to god what my people swear"). There are also forms where "gods" is substituted for "god".[3] The word thúath (a conjugation of túath) is translated here as "people", but is occasionally also translated as "tribe".[4][5]

Interpretation

[edit]

This oath has frequently been interpreted as a hangover of Celtic pagan Ireland, preserved in early Irish literature.[6] Joseph Vendryes made a connection with the Celtic god Teutates, a tribal deity whose name has the same root as thúath,[7] a proposal which has been followed by Myles Dillon[8] and Proinsias Mac Cana.[5] Gearóid Mac Niocaill proposed that the pagan god behind this oath was the tribe's ancestor god, and Kenneth H. Jackson that he was its tutelary god.[6] Kevin Murray argues that a phrase from the Old Irish poem Scéla Mosauluim can be construed as giving the name of the god behind this oath as Tigernmas, though he admits "the balance of probability" is against it.[9]

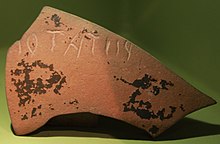

The aspect of taboo in the oath (which avoids the name of the god being sworn by) has also been noted.[10] Vendryes argued that the suppression of the name of the god in an oath to that god was typical of Celtic religion. He compares it to Strabo's reference to a nameless god of the Celtiberians, and Lucan's poetic description in the Pharsalia of Gauls dreading gods whom they do not know.[7] John T. Koch proposed that the formula, alongside the Welsh oath tyghaf tyghet ("I swear a destiny on you") and a Gaulish phrase from the Chamalières tablet,[a] originated as a taboo alteration of an oath sworn to Lugus (a god whose name, he argues, derives from a Celtic word for oath).[12] Stefan Schumacher and Thomas Charles-Edwards have argued that identifying the Welsh and Irish oaths poses difficulties, as the pun in the Welsh oath between tyngaf 'to swear' and tynghaf 'to destine' relies on phonological developments unique to Middle Welsh, not traceable to proto-Celtic, where the words are distinct.[13]

Against the identifications of the phrase as a remnant of pagan culture, Ó hUiginn has argued that the phrase "has every appearance of being a contrived learned phrase", an innovation in the early Irish epics dating to the Christian period rather than "an inherited pre-Christian archaism".[14] He argues that the archaic grammatical features in this phrase show a "syntactic imbalance", which would be unexpected in a genuine idiomatic expression. His proposal is that a Christian author attempted to contrive an archaic pagan oath (suitable to the pagan background of the Old Irish epics) out of the Christian formula toing do dia ("I swear to god").[15] Kim McCone and Tom Sjöblom have followed Ó hUiginn's analysis.[16][13]

Calvert Watkins, who points to "conservative nature of the [Irish] language and of oath-taking in general", has paralleled this oath with two others from Indo-European languages: (1) an oath of the Kievan Rus' from the Primary Chronicle, "May we be accursed of the god whom we worship",[b] and (2) an oath from a litany of the mysteries of Isis, "I swear by the gods whom I worship".[c] He suggests that these oaths, with the peculiar feature of invoking one's own gods in a restrictive relative clause, ultimately derive from an Indo-European source.[17] Watkins does not agree with Ó hUiginn that the phrase shows "syntactic imbalance". He considers Ó hUiginn's proposed explanation of the phrase "most unlikely", in view of the absence of documentation for this development, and the small number attestations of the Christian formula.[18]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The phrase in question is toncnaman toncsiiontio (lines 7-8), which is of uncertain meaning.[11] For discussion, see Schmidt 1981, pp. 266–267, Koch 1992, pp. 249–251, and Lambert 2002, pp. 278–279.

- ^ Original Church Slavonic: "da iměemŭ kljatvŭ otŭ boga vů níže věruemů".[17]

- ^ Original Greek: "epómnumai dè kai hoùs proskunō theoús".[17] For more on this oath see Burkert 1987, p. 50.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Ó hUiginn 1989, p. 332.

- ^ a b Watkins 1990, p. 48.

- ^ Ó hUiginn 1989, pp. 332–336.

- ^ McCone 1991, p. 234.

- ^ a b Mac Cana 1970, p. 23.

- ^ a b Ó hUiginn 1989, p. 338.

- ^ a b Vendryes 1948, p. 33.

- ^ Dillon 1964, p. 60.

- ^ Murray 2003.

- ^ Sjöblom 2000, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Lambert 2002, pp. 278–279.

- ^ Koch 1992, pp. 252, 261.

- ^ a b Sjöblom 2000, p. 98.

- ^ Ó hUiginn 1989, p. 340.

- ^ Ó hUiginn 1989, pp. 338–339.

- ^ McCone 1991, pp. 234–235.

- ^ a b c Watkins 1989, p. 792.

- ^ Watkins 1990, pp. 48–50.

Bibliography

[edit]- Burkert, Walter (1987). Ancient Mystery Cults. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03387-0.

- Dillon, Miles (1964). "Celtic religion and Celtic society". In Raftery, Joseph (ed.). The Celts. Cork / Dublin: The Mercier Press. pp. 59–71.

- Koch, John Thomas (1992). "Further to tongu do dia toinges mo thúath, &c". Études Celtiques. 29: 249–261. doi:10.3406/ecelt.1992.2008.

- Lambert, Pierre-Yves (2002). "L-100". Recueil des inscriptions gauloises. II, fasc. 2, Textes gallo-latins sur instrumentum. Paris: Éd. du CNRS. pp. 269–280.

- Mac Cana, Proinsias (1970). Celtic Mythology (1st ed.). Feltham: Hamlyn.

- McCone, Kim (1991). Pagan Past and Christian Present in Early Irish Literature. Maynooth Monographs. Vol. 3. Maynooth: An Sagart.

- Murray, Kevin (2003). "A reading from Scéla Moṡauluim". Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie. 53 (1): 198–201. doi:10.1515/ZCPH.2003.198.

- Ó hUiginn, Ruairí (1989). "Tongu do dia toinges mo thúath and related expressions". In Ó Corráin, D.; Breatnach, L.; McCone, K. (eds.). Sages, Saints and Storytellers: Celtic Studies in Honour of Professor James Carney. Maynooth: An Sagart. pp. 332–341.

- Schmidt, K.-H. (1981). "The Gaulish inscription of Chamalières". Bulletin of the Board of Celtic Studies. 29: 256–268.

- Sjöblom, Tom (2000). Early Irish Taboos: A Study in Cognitive History. Helsinki: University of Helsinki. ISBN 978-951-45-9071-9.

- Vendryes, Joseph (1997) [1948]. La religion des Celtes. Spézet: Coop Breizh.

- Watkins, Calvert (1989). "New parameters in historical linguistics, philology, and culture history". Language. 65 (4): 783–799. JSTOR 414934.

- Watkins, Calvert (1990). "Some Celtic phrasal echoes". In Matonis, A. T. E.; Melia, D. F. (eds.). Celtic Language, Celtic Culture: A Festschrift for Eric P. Hamp. Van Nuys, CA: Ford & Bailie. pp. 47–56.

Further reading

[edit]- Breatnach, Liam (1980). "Some remarks on the relative in Old Irish". Ériu. 31: 1–9. JSTOR 30008209.

- Charles-Edwards, Thomas (1995). "Mi a dynghaf dynghed and related problems". In Eska, J. F.; Gruffydd, R. G.; Jacobs, N. (eds.). Hispano-Gallo-Brittonica: Essays in Honour of Prof. Ellis Evans. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. pp. 1–15.

- Dictionary of the Irish Language, s.v., "tongaid".

- Ó Murchú, Liam P. (1992). "The literary asseveration in Irish". Études Celtiques. 29: 327–332. doi:10.3406/ecelt.1992.2015.

- Schumacher, Stefan (1995). "Old Irish *tucaid, tocad and Middle Welsh tynghaf tynghet re-examined". Ériu. 46: 49–57. JSTOR 30007873.