Theodore Bachenheimer

Theodore Herman Bachenheimer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s) | The G.I. General |

| Born | April 23, 1923 Braunschweig, Free State of Brunswick. Weimar Republic |

| Died | October 22, 1944 (aged 21) 't Harde, German-occupied Netherlands |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1942–1944 |

| Rank | Private first class |

| Battles / wars | World War II |

| Awards | |

| Spouse(s) |

Ethel Lucille Murfield

(m. 1943) |

| Relations | Katherina Bachenheimer (mother), Wilhelm Bachenheimer (father), Klaus Gutmann Bachenheimer (brother), Theodore Bachenheimer (uncle) |

Theodore Herman Bachenheimer (23 April 1923 – 23 October 1944), was an American soldier. In just three years, he achieved legendary status as one of the war's most daring reconnaissance scouts, he was better known as The Legendary Paratrooper or The G.I. General and was befriended by Martha Gellhorn.[note 1][1]

Private Bachenheimer had an extraordinary talent for war, but, in reality was a man of peace. 'In principle I am against any war,' he would say, 'I simply cannot hate anyone'.[2]

Held in high esteem by his fellow combatants, remembered by high ranking U.S. Army officers, Lieut. General James M. Gavin once said of him,'His bravery was, beyond question, of an exceptional high order. Bachenheimer stood out more from the venturesome his bravery took than because of the bravery itself'.

He chose to finish the task he started whatever the sacrifice. Bachenheimer, one of the most remarkable characters of his division, died at the age of twenty-one.

Biography

[edit]Bachenheimer was born in Braunschweig, Germany, the eldest of two sons. His father Wilhelm, born in Frankenberg, Hesse, Germany (1892–1942), a former student at the Music Academy of Frankfurt[3] and of German baritone nl:Eugen Hildach (1849–1924), was a musician, a singer and a lecturer of Jewish descent who served in the German Army during World War I (1914–16) and was once musical director of opera singer Maria Jeritza and voice teacher and coach of American actress Joan Blondell. His mother Katherina Boetticher (1899–1985) was an actress, his uncle and namesake (1888–1948), was a producer of light opera based in Hollywood,[4] The Merry Widow and The Waltz King are among the works he either directed or produced.[5] He also worked as an opera director for the California Opera Association; notably staging a production of Mozart's The Magic Flute at the Wilshire Ebell Theatre in Los Angeles in June 1942 with Marilyn Cotlow as The Queen of the Night, George London as Papageno and Johnny Silver as Monostatos.[6]

Following Hitler's rise to power, the Bachenheimers moved, firstly to Prague and afterwards to Vienna, sometime in September 1934 they boarded the Majestic in Cherbourg, France, and sailed for America, arriving in New York City on 19 September and finally settled in California. Because of his family background, Bachenheimer registered aged 18 years old as an arts student at the Los Angeles City College with the intention of becoming an opera singer. Prior to his U.S. army years, Bachenheimer worked briefly as a press agent for an ill-fated theatrical production.

Military

[edit]After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Bachenheimer volunteered for military service (13 December 1941[7]), and in May 1942[clarification needed] he was allocated to the 504th Infantry Regiment after successfully obtaining his parachuting certificate. In August 1942, he was transferred to Fort Bragg, North Carolina together with the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment which was attached to the 82nd Airborne Division. While the 504th was training at Fort Bragg, Bachenheimer, fluent in German, taught an intelligence class, where he would read out of a German infantry training manual.[8] Bachenheimer was granted U.S. citizenship on 23 October 1942 by the United States district court of Atlanta, Georgia, his petition for naturalization described him as a 5 ft 10, 160 lbs white male with brown hair and brown eyes, ruddy complexion, exhibiting a small scar on the tip of the chin.[9] On 23 March 1943, in Fayetteville, Cumberland County, North Carolina, he married Ethel Lou Murfield, whom he called Penny, from Fullerton, California who at the time was working for the Douglas Aircraft Company as a timekeeper.[10]

Bachenheimer took part in Operation Husky, fought in the battles for Salerno and Anzio, where his bravery[11] behind enemy lines made him a legend in the 82nd Airborne Division, earning him the nickname of The Legendary Paratrooper. From 1942 to 1944, Bachenheimer was the subject of articles in newspapers such as Star and Stripes, Collier's Weekly and the Los Angeles Times, and some of his exploits were broadcast in radio dispatches.

In action during Operation Market Garden, he landed near Grave, the Netherlands, on 17 September 1944. After entering the city he met with a Dutch resistance member who introduced him to a local underground group, its leaders fled fearing a German ruse and the remaining members asked Bachenheimer to be their leader (with the underground rank of Major[12]) of the Dutch resistance group in Nijmegen called K.P. (Knokploegen, part of the newly formed Netherlands Forces of the Interior, who, in an ironic twist of fate, had accepted Prince Bernhard as their chief commander). It was in their midst that he was nicked The G.I. General, his army was known as The Free Netherlands Army, a Battalion consisted of more than three hundred fighters.[13] His partisans dubbed him Kommandant, Bachenheimers's HQ was set up in a steel factory situated in Groenestraat, south-west part of Nijmegen. By the end of September, Bachenheimer had moved his HQ to a primary school[11] situated just south of the steel factory. Bachenheimer's seconds-in-command, two other paratroopers of the 504th, were known as Bill One (Willard M. Strunk of Abilene, Kansas) and Bill Two (Bill Zeller of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, killed in action, Apr 7, 1945). Bachenheimer's resistance troop successfully[14] gathered intelligence about the occupation forces and the information was then transmitted forward to the 82nd Airborne Division and other allied officers who came to Bachenheimer for intel.

For his heroic actions in Nijmegen, Bachenheimer was recommended for a battlefield commission and was directed to report to division for an interview by a board of officers. On his way to his interview he picked up a helmet with a first lieutenant's bar on it, and was sent back for reconsideration.[14] Finally, Bachenheimer agreed to a battlefield commission as a second Lieutenant.[15]

The Windmill Line

[edit]According to statements by Airey Neave, he accompanied British intelligence officer Captain Peter Baker and PFC Bachenheimer for their crossing of the Waal river near Tiel on the night of 11–12 October[16] as he sent them on a secret mission to organize a rescue line named 'Windmill'. They were to set up their HQ working from a local resistance hotbed, the Ebbens family's farm, near Zoelen and the village of Drumpt[note 2] In addition to Bachenheimer and Baker, the other boarders at Ebbens's house were a group of young Dutchmen, a Jewish family, a wounded British paratrooper, Staff-Sergeant Alan Kettley of the Glider Pilot Regiment and Canadian military officer, Lieutenant Leo Jack Heaps (1922–1995). Heaps would be involved with Operation Pegasus, he would be later raised to the rank of Captain and awarded the Military Cross, his son is Canadian politician, Adrian Heaps. It was to prove IS 9's last mission under the command of James Langley[19] and fatal to Bachenheimer and Fekko Ebbens. Operation Windmill might have been used by the British Secret Intelligence Service as a justification for a Covert operation: Many of Neave's statements concerning the operation are at odds with Baker's[20] and Heaps's:[21] Captain Peter Baker and Lieutenant Leo Heaps stated that Bachenheimer volunteered to join Baker's secret HQ [22] but that Bachenheimer arrived a day or two after Baker's arrival.[21][20] Baker had been tasked to deploy the Operation codenamed 'Windmill' to establish the Windmill Line[note 3] on site. The goal was to bring back British paratroopers hidden by Dutch resistance in the Arnhem area (Ede, Netherlands) safely to the Allied lines after the failure of Market Garden using local resistance members as guides. Bachenheimer was also determined to establish telephone contact between areas of Germany and the Netherlands opposite his divisional front.[24]

Raided: Betrayal, arrest and interrogations

[edit]On the night of 16 October, three days after glider pilot Kettley left, the Ebbens's farm was raided by the Wehrmacht, two German soldiers were killed[25] and during their search, the Germans found a stock of arms and some papers. Ebbens was in the middle of a meeting with one of the resistance leaders for the Betuwe region.[26] when his farm was raided. IS9 was first informed of the raid around 2am in the early morning hours of 17 October by a local resistance member who crossed the river to inform them that both men had died. Neave consequently blamed Baker and Bachenheimer for the failed operation: According to Major Airey Neave[27] (codenamed Saturday[28]), Baker and Bachenheimer disobeyed a written order[note 4] to remain in military uniform and not to leave the safe house during daylight hours, despite the nature of their tasks being at practical odds with such an instruction[30] and Neave praising and recruiting Leo Heaps who himself had abandoned the Ebbens farms shortly before the raid took place during daytime hours wearing civilian clothing rushing to flee a German patrol who had stopped him.

The truthfulness of Airey Neave's claims and the motivation behind his putting the blame squarely on Baker and Bachenheimer is highly questionable. Neave may have been misinformed initially about Baker and Bachenheimer not wearing their uniforms, since the men were in bed when the raid took place around 0:30am on 17 October and the Germans took some time to discover 2 allied uniforms. The Germans initially misidentified their captives as including one Englishman and one Canadian, quite probably based on the Canadian uniform jacket left behind by Leo Heaps. Airey Neave failed to mention master scout Bachenheimer's work in the Betuwe region near Driel and Renkum[31] in the days and weeks leading up to the crossing where the successful rescue mission later known as Operation Pegasus took place.

Following their arrest, Bachenheimer and Baker were brought to a local school in Zoelen where they were interrogated for some hours, but they remained unmolested. They managed to establish a false identity and said they were cut off from their units and had lost their way in a no man's land between the Waal and the Rhine.[27] The two men were taken to a POW transit camp[11] at Culemborg, from where they and other captives had to march 30 miles to another POW camp situated at Amersfoort. After the Germans had camouflaged their trains with freshly cut tree branches to protect against allied air raids, Bachenheimer and Baker were put in separate boxcars on a transport train to Stalag XI-B, Fallingbostel. Before boarding, Bachenheimer and Baker gave each other messages for friends hoping one day to meet again in Los Angeles:[32]

Maybe we can do business together, we could start a Californian branch of your firm and call it 'The Mouseketeers'[33] said Bachenheimer to Baker.

Baker would reach the camp on the night of 26 October, (when news that both men had been arrested, the "Windmill line" was abandoned, the other escape route via Renkum codenamed Operation Pegasus went ahead as scheduled.[29]). Fekko Ebbens was moved to Renswoude on 14 November[26] and shot in retaliation for terrorist activity, his farm was burned to the ground.

Death

[edit]The intrepid Bachenheimer managed to escape at night (20–21 October) from his boxcar with three other allied soldiers,[34] one of whom mentioned the American paratrooper insisted he would be the last to make the jump to safety. They waited for Bachenheimer along the tracks, but he did not surface and probably jumped off a bit further north between Harderwijk and Nunspeet. Bachenheimer was recaptured for the last time by the Germans somewhere between Nijkerk and the village of 't Harde, possibly trying to reestablish contact with his resistance force. According to unnamed local sources, around 9pm on 22 October or 4am on 23 October, a Wehrmacht truck stopped along the Eper(grind)weg[11] in 't Harde, in front of the house of the De Lange family when three gunshots were heard. Later that morning, the German Commander of a nearby army base ('Truppenübungsplatz Oldebroek') had the local municipality fetch Bachenheimer's body from the base. His body exhibited two gunshot wounds, one in his neck and one in the back of his head, both deemed lethal. Among the few items retrieved from Bachenheimer's body, were personal papers, his Dog tags, suspenders, his gold wedding ring and a silver ring engraved with the inscription Ik hou van Holland ("I love Holland"). A memorial monument marks the spot where he was probably shot, although no confirmed eyewitness reports are known by name and some doubt remains as to the exact moments and motivation leading up Bachenheimer's death.

Bachenheimer was due to be given the rank of 2nd lieutenant within a month.[35]

Every year, on Dutch National Remembrance day (4 May), a wreath is laid at his memorial monument site at Eperweg in 't Harde. The monument is maintained by local school children.

In April 1946, Bachenheimer's remains were recovered from Oldebroek General Cemetery "De Eekelenburg" and reburied at the U.S. Military Cemetery at Neuville-en-Gondroz in Belgium. In April 1949, at the request of his mother, Bachenheimer's body was repatriated to the U.S. and reburied in the Beth Olam Jewish Cemetery located at the Hollywood Forever Cemetery in Hollywood, California.[11]

Heaps's book

[edit]Canadian military officer Leo Heaps set the date of his arrival at Ebbens's farm (in company of Kettley) on 3 October, Bachenheimer and Baker were already there. Heaps dated his departure on 5 October, putting Kettley in charge of securing the property. Heaps's The Grey Goose of Arnhem, published in 1976, contradicts Neave's version of the story, published in 1969 as well as that of Baker published in 1946, casting some serious doubts on the entire chronology of events.

Leo Heaps insisted he wanted to leave the farm since he suspected an upcoming German raid. Dressed in civilian clothing, he was escorted to the river by members of the resistance. In the middle of Tiel, a German stronghold, Heaps's bicycle suffered a flat tire and he had to walk as the other resistance members accompanying him cycled on. When he passed a group of German soldiers, one of them placed a hand on his shoulder to stop him and Heaps dashed off on his bicycle, unharmed, leaving the German patrol to wonder what just happened according to Heaps's own memoir.[36] Upon crossing the river back to safety, Heaps was invited by Airey Neave to join his intelligence outfit IS-9. Heaps was never blamed by Airey Neave for not wearing his uniform during daytime hours despite potentially endangering the Ebbens farm of being shot as a spy. Nor did Heaps and Neave ever mention how the Germans had sent a quisling member of the Abwehr by the name of Johannes Dolron[37] to stay at the Ebbens farm around the time of Heap's departure and near apprehension in early October. Dolron arrived around the time of Heaps's flee for safety and Dolron left the farm after 12 days, only to inform the local German command of the goings on at the farm just prior to the raid.[38]

Dutch resistance leader, Christiaan Lindemans questioning[39] at Camp 020, may give indirect evidences to support Heaps's claims. During his interrogation by MI-9 agents, Lindemans mentioned a trip he made to Eindhoven, returning the same evening, ordered by Prince Bernhard on 21 October 1944 to talk with Peter, leader of a resistance group in Eindhoven. Just like this Peter, Baker was the chief of a resistance group in the Netherlands and connected with Eindhoven. Lindemans acknowledged that he had given the name of Captain Baker to a FrontAufklärungsTruppe (FAT) on 15 September 1944 at the Abwehr station in Driebergen. There is a strong possibility that Bachenheimer and Baker's captures were the result of a German counterintelligence operation based on details supplied by Bernhard sent Lindemans or the escape and near apprehension of Leo Heaps.

Military decorations

[edit]On 14 June 1944, Bachenheimer was awarded the Silver Star for gallantry in action demonstrated during the fighting for Anzio, and on 7 January 1952 (by Royal Decree n°24, signed by her HRH Queen Juliana of the Netherlands), was awarded posthumously the Bronze Cross[note 5] for distinguished and brave conduct against the enemy at Nijmegen.

| " | It seems to me that these young boys who paid with their lives are forgotten very soon. But i have not forgotten and i never will.[40] | " |

| – Katherina Bachenheimer, Letter to the Quartermaster General of the Memorial Division, 12 March 1947 | ||

Remembering Private Bachenheimer

[edit]Bachenheimer is eligible[41][42] for the award of the Medal of Honor for his outstanding leadership, gallantry and exceptional devotion to duty during World War II but also for a posthumous promotion and for reburial in Arlington National Cemetery.

In popular culture

[edit]

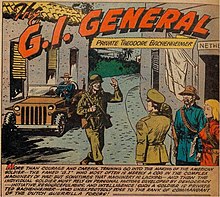

Bachenheimer was featured in the Real Life comics issue n°25, published 1 September 1945, as the character of the G.I. General.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Gellhorn met Bachenheimer through Baker.

- ^ Ebbens's address[17] had been given by Dignus Kragt (1917-2008) also known as Frans Hals, Kragt was a member of the SAS Belgian Regt of Operation Fabian (16 Sept 1944-14 March 1945) and an MI-9 agent. Operation Fabian was to collect intelligence concerning enemy concentrations in the northwest Netherlands and to locate V-2 rocket launch sites.[18] Belgian born Gilbert Sadi-Kirschen (codenamed Captain Fabian King) was head of Operation Fabian, Sadi-Kirschen and his team were dropped in the Netherlands 48 hours before Operation Market-Garden would begin, King's unit became part of Operation Pegasus. On 23 July 1948, Captain Dignus Kragt of the Intelligence Corps (345755) was awarded the Medal of Freedom with gold palm and on 15 February 1952 the Bronze Lion. Kragt assisted fellow officer, Brigadier John Hackett in his escape.

- ^ The Windmill incident was the subject of a post-war enquiry.[23]

- ^ On 6 October, Neave asked IS9's Langley (codenamed P15) the permission to send Baker across enemy lines, Langley agreed on condition that Baker remained in uniform at all times.[29]

- ^ Dutch counterpart of the British Distinguished Service Order.

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ Baker (1946), p. 141.

- ^ Gellhorn, Martha (December 2, 1944). "Rough and Tumble". Collier's Weekly: 70.

- ^ Music and Dance in California and the West. Vol. II (1940). Bureau of Musical Research, Hollywood, edited by José Rodriguez and compiled by William J. Perlman.

- ^ "The Final Curtain". The Billboard. 20 November 1948. p. 53.

- ^ "Chicago Stagebill Yearbook", 1947.

- ^ Isabel Morse Jones (27 June 1942). "'The Magic Flute' Given With English Book At Ebell". Los Angeles Times. p. 9.

- ^ United States World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946.

- ^ Tyler Fox interview of Baldino, Fred J. Corp. Co. A, 504th Para. Inf. Feb. 15, 2013.

- ^ Georgia, Naturalization Records, 1793-1991.

- ^ North Carolina, County Marriages 1762-1979.

- ^ a b c d e A. Visser - Het verhaal achter ons monument (mei, 1980)

- ^ Baker (1946), p. 140.

- ^ Gavin (1978).

- ^ a b Nordyke (2008)

- ^ Breuer, William B. Daring Missions of World War II. John Wiley & Sons.

- ^ Neave (1969).

- ^ Foot, Langley (1979).

- ^ Davies (1998).

- ^ Routledge (2002), p. 153.

- ^ a b Baker, Peter (1955). My testament. Calder. OCLC 493089578.

- ^ a b Heaps, Leo (6 April 2020). The grey goose of Arnheim : the story of the most amazing mass escape of World War II. Sapere Books. ISBN 978-1-913518-11-0. OCLC 1353782781.

- ^ Foot, M.R.D.; Langley, James (1979). MI9: The British Secret Service That Fostered Escape and Evasion 1939-1945, and its American Counterpart. London. p. 223.

- ^ Routledge (2002), p. 152.

- ^ Baker (1946), Strijkert Investigation (2023)

- ^ Neave (1969), p. 308.

- ^ a b Heaps (1976).

- ^ a b Neave, Airey (1969). The Escape Room. Doubleday. p. 305.

- ^ Neave (2010).

- ^ a b Routledge (2002).

- ^ De Jong, Loe (1981). Het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in de tweede wereldoorlog. Staatsuitgeverij. ISBN 90-12-03401-9. OCLC 489963450.

- ^ Leo., Heaps, The Grey Goose of Arnhem : The Story of the Most Amazing Mass Escape of World War II, ISBN 978-1-7052-8096-6, OCLC 1232475442, retrieved 2023-01-17

- ^ Baker (1955), p. 150.

- ^ Baker (1955).

- ^ Baker (1955), pp. 151–152.

- ^ Baker (1946), p. 156.

- ^ Leo Heaps - The Grey goose of Arnhem

- ^ De Betuwe In Stelling - Victor Laurentius

- ^ Laurentius, Victor (2000). De Betuwe in stelling : de ondergrondse, 1940-1945 & de stellingenoorlog en de evacuatie 1944-1945. Arend Datema Instituut. ISBN 90-801173-9-0. OCLC 67642292.

- ^ "German Intelligence Agents and Suspected Agents, Christian Lindemans, alias Christian Brant, German codename King Kong", 1944 Nov 10-1944 Nov 19, Reference KV 2/233, National Archives

- ^ Van Lunteren (2014).

- ^ Thompson, James G. (September 2003). Complete Guide to United States Marine Corps Medals, Badges and Insignia: World War II to Present. Medals of America Press.

- ^ Dalessandro, Robert J. Army Officer's Guide. Stackpole Books.

Bibliography

- Baker, Peter (1946). Confession of Faith. Falcon Press.

- Baker, Peter (1955). My Testament. London: John Calder.

- Baldino, Fred (2001). "Odyssey of the PFC General". The Airborne Quarterly.

- Van Lunteren, Frank; Margry, Karel (2002). "The Odyssey of Private Bachenheimer". After the Battle.

- Carter, Ross S. (1996). Those Devils in Baggy Pants. Buccaneer Books.

- De Groot, Norbert A. (1977). Als Sterren Van De Hernel [Like Stars from Heaven].

- François, Bill (1961). "The Legendary Paratrooper". Veterans of Foreign Wars.

- Lofaro, Guy. The Sword of St. Michael: The 82nd Airborne Division in World War II. Da Capo Press.

- Loomis, William Raymond (1958). Fighting Firsts. Vantage Press.

- Neave, Airey (1969). The escape room. Doubleday.

- Heaps, Leo (1976). The Evaders. New York: Morrow.

- Gavin, James M. (1978). On to Berlin. New York: Viking Press.

- Foot, M.R.D.; Langley, J.M (1979). MI 9 – the British Secret Service That Fostered Escape and Evasion, 1939-1945 and its American Counterpart. London.

- Davies, Barry (1998). The Complete Encyclopedia of the SAS. Virgin Publishing.

- Nordyke, Phil (2008). More Than Courage: Sicily, Naples-Foggia, Anzio, Rhineland, Ardennes-Alsace, Central Europe: Combat History of the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment in World War II. Zenith Press.

- Routledge, Paul (2002). Public Servant, Secret Agent: The Elusive Life and Violent Death of Airey Neave. Fourth Estate.

- Neave, Airey (2010). Saturday at M.i.9: The Classic Account of the Ww2 Allied Escape Organisation. Pen & Sword Military.

- Bowman, Martin W. (2013). The Shrinking Perimeter. Pen & Sword Aviation.

- Van Lunteren, Frank (2014). The Battle of the Bridges The 504 Parachute Infantry Regiment in Operation Market Garden. Casemate Publishers.

External links

[edit]- About Face The Story of the Jewish Refugee Soldiers of World War II: [1]

- 1923 births

- 1944 deaths

- Jewish emigrants from Nazi Germany to the United States

- Jewish American military personnel

- United States Army personnel killed in World War II

- Recipients of the Silver Star

- Recipients of the Bronze Cross (Netherlands)

- Burials at Hollywood Forever Cemetery

- United States Army soldiers

- 20th-century American Jews