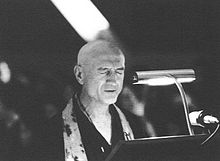

Philip Kapleau

Philip Kapleau | |

|---|---|

| |

| Title | Roshi |

| Personal life | |

| Born | August 20, 1912 New Haven, Connecticut, United States |

| Died | May 6, 2004 (aged 91) |

| Nationality | American |

| Religious life | |

| Religion | Buddhism |

| School | Zen Buddhism |

| Lineage | Independent |

| Senior posting | |

| Based in | The Rochester Zen Center |

| Successor | Bodhin Kjolhede |

Students

| |

| Part of a series on |

| Zen Buddhism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Western Buddhism |

|---|

|

Philip Kapleau (August 20, 1912 – May 6, 2004) was an American Zen Buddhist teacher. He trained in the Harada–Yasutani tradition, which is rooted in Japanese Sōtō and incorporates Rinzai-school koan study. He established Rochester Zen Center, which grew to become one of the most influential Zen communities in the West.[1][2] His independent lineage includes teachers active in the USA, Canada, Costa Rica, Mexico, Sweden, Finland, Germany, the UK and New Zealand.[3]

Early life

[edit]Kapleau was born in New Haven, Connecticut. As a teenager he worked as a bookkeeper. He briefly studied law and later became an accomplished court reporter. In 1945 he served as chief Allied court reporter for the Trial of the Major War Criminals Before the International Military Tribunal, which judged the leaders of Nazi Germany. It was the first of the series commonly known as the Nuremberg Trials.

Kapleau later covered the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, commonly known as the Tokyo War Crimes Trials. While in Japan he became intrigued by Zen Buddhism. He became acquainted with Karlfried Graf Dürckheim, then a prisoner at Sugamo Prison, who recommended that Kapleau attend informal lectures given by D.T. Suzuki in Kita-Kamakura.[4] After returning to America, Kapleau renewed his acquaintance with D.T. Suzuki who had left Kita-Kamakura to lecture on Zen at Columbia University. Disaffected with a primarily intellectual treatment of Zen, he moved to Japan in 1953 to seek its deeper truth.

Zen training

[edit]He trained initially with Soen Nakagawa, then rigorously with Daiun Harada at the temple Hosshin-ji. Later he became a disciple of Hakuun Yasutani, a dharma heir of Harada.[5] After 13 years' training, Kapleau was ordained as a priest by Yasutani in 1965 "according to the rites prescribed by the Patriarch Eihei Dogen" as described by Yasutani in a certificate from the Sanbo "Three Treasures" Buddhist Religious Association, dated June 28, 1964, and given permission to teach.

Work and teaching

[edit]Three Pillars of Zen

[edit]During his time in Japan, Kapleau transcribed other Zen teachers' talks, interviewed lay students and monks, and recorded the practical details of Zen Buddhist practice. His book, The Three Pillars of Zen, published in 1965, has been translated into 12 languages, and is still in print.[6][7] It was one of the first English-language books to present Zen Buddhism not as philosophy, but as a pragmatic and salutary way of training and living. James Ishmael Ford has described the book as monumentally important, stating "I cannot express how important that single book was in my life; and this has been true for so many others who've taken up the Zen way".[8]

Rochester Zen Center and wider sangha

[edit]

During a book tour in 1966, he was invited to teach meditation at a gathering in Rochester, New York, which led to the founding of the Rochester Zen Center.[1][9] Affiliate centers were founded around the world, including in Canada, Poland, Costa Rica, Germany, Sweden, Mexico and the UK.[10]

For almost 40 years, Kapleau taught at the Center and in many other settings around the world, and provided his own dharma transmission to several disciples.

He also introduced many modifications to the Japanese Zen tradition, such as chanting the Heart Sutra in the local language. He often emphasized that Zen Buddhism adapted so readily to new cultures because it was not dependent upon a dogmatic external form. At the same time he recognized that it was not always easy to discern the form from the essence, and one had to be careful not to "throw the baby out with the bathwater".

Break with Yasutani

[edit]

Kapleau ended his relationship with Yasutani formally in 1967 over disagreements about teaching as well as Kapleau's reservations about the conduct of Eido Shimano, whose pattern of sexual relationships with and alleged sexual harassment of female students was later exposed.[11][1] In a letter to Yamada Koun Roshi,[12] Kapleau wrote:

I never pretended to be [a dharma heir of Yasutani Roshi]. I have only said that he gave me permission to teach, and that is true. The first year he came to Rochester he gave me permission to hold daisan. He told me I could do that until he returned to the United States the following year, at which time he would have a public ceremony for me if everything went all right in the meantime. Unfortunately, everything did not go all right in the interim. Many things happened involving Eido Shimano, who was living in New York at that time. As a result of Eido’s behavior, when Yasutani Roshi came to New York the following year I phoned him and told him not bring Eido with him to Rochester. This was a foolish thing for me to say to the Roshi and he obviously resented it, because when he came to Rochester to hold a 7-day sesshin later on he was angry with me. I don't blame him. But I did apologize to him at the time. In any case, he refused to hold the ceremony. You should also know that before I left Japan Yasutani Roshi gave me a certificate saying I could ask as a missionary teacher for his sect of Zen. [...] Not only did he give me this certificate but he also gave me one of this robes and bowls. I interpreted this as evidence of our deep relationship at the time as an ordained disciple of his.

— Letter to Yamada Koun Roshi, February 17, 1986

According to James Ishmael Ford, "Kapleau had completed about half of the Harada-Yasutani kōan curriculum, the koans in the Gateless Gate and the Blue Cliff Record,"[2] and was entitled to teach, but did not receive dharma transmission. According to Andrew Rawlinson, "Kapleau has created his own Zen lineage."[13]

Kapleau's dharma heir Bodhin Kjolhede has been offered tranmission in the Sōto lineage, which he declined. He explained his decision in a teisho:

Since I never worked extensively with any Soto teacher, such certification would, I believe, be a mere formality, and contrary to the spirit of Zen’s ‘mind-to-mind transmission.’ Roshi Kapleau’s seal – and now my twenty years of teaching experience – is more than enough for me.

— Teisho given by Roshi Bodhin Kjolhede on January 8, 1995

Writings

[edit]Kapleau was an articulate and passionate writer. His emphasis in writing and teaching was that insight and enlightenment are available to anyone, not just austere and isolated Zen monks. Also well known for his views on vegetarianism, peace and compassion, he remains widely read, and is a notable influence on Zen Buddhism as it is practiced in the West. Today, his dharma heirs and former students teach at Zen centers around the world.

Kapleau's book To Cherish All Life: A Buddhist Case for Becoming Vegetarian condemns meat-eating. He argued that Buddhism enjoins vegetarianism on the principle of nonharmfulness.[14]

Grist for the mill

[edit]A favorite saying of Philip Kapleau was "grist for the mill" which means that all of our troubles and trials can be useful or contain some profit to us. In this spirit, his gravestone is one of the millstones from Chapin Mill, the Buddhist retreat center whose land was donated by a founding member of the Rochester Zen Center, Ralph Chapin.[15]

Later life and death

[edit]He suffered from Parkinson’s Disease for several years. While his physical mobility was reduced, he enjoyed lively and trenchant interactions with a steady stream of visitors throughout his life. On May 6, 2004, he died peacefully in the backyard of the Rochester Zen Center, surrounded by many of his closest disciples and friends.

Lineage

[edit]Kapleau appointed several successors, some of whom have subsequently appointed successors or authorized teachers:[3]

- Bishop, Mitra (born 12 April, 1941). Founder and head of the Mountain Gate monastic center, NM and the Hidden Valley Zen Center, CA.

- Henry, Michael Danan (born 12 November, 1939). Also a teacher appointed by Robert Aitken. Founding teacher at the Zen Center of Denver (now teacher of Old Bones Sangha).

- Kempe, Karin Roshi. Teacher at the Denver Zen Center. In 2008 the Head of Zendo at Zen Center of Denver.

- Morgareidge, Ken. Teacher at the Denver Zen Center until 2021 [186]. Currently teaching independently. In 2005-2007 the Head of Zendo at Zen Center of Denver.

- Sheehan, Peggy. Teacher at the Denver Zen Center [186]. In 2001-2005 the Head of Zendo at Zen Center of Denver.

- Martin, Rafe. Teacher at Endless Path Zendo, author.

- Holmgren, Hoag. Teacher at Mountain Path Sangha, author.

- Gifford, Dane Zenson (1949–2016). Former teacher at the Toronto Zen Centre.

- Graef, Sunyana (born 1948). Former teacher at the Toronto Zen Centre, head of the Vermont Center. Teacher at the Casa Zen in Costa Rica.

- Henderson, Taigen (born 1949) Since 2005 Dharma Heir of Sunyana Graef and the abbot of the TZC. Teacher at the Toronto Zen Centre.

- Kjolhede, Peter Bodhin (1948-). Abbot at the Rochester Zen Center and founder of the “Cloud-Water Sangha”.[16]

- Odland, Kanja (born 1963). Ordained as a priest in 1999 and authorised to teach by Kjolhede in 2001. Teacher at Zengården, the head temple and retreat center of the Swedish Zen Buddhist Society (Zenbuddhistiska Samfundet).

- Ross, Lanny Sevan Keido Sei'an (born 7 September, 1951). Also holds the Dharma Transmission in the Jiyu Kennett and Robert Aitken lineages bestowed on him in 2007 by James Zeno Myoun Ford. Former teacher at the Chicago Zen Center in Evanston, IL, US.

- Poromaa, Mikael Sante (born 1958). Ordained as a Zen priest in 1991. Kjolhede gave him sanction to teach in 1998. Teacher at Zengården, the head temple and retreat center of the Swedish Zen Buddhist Society (Zenbuddhistiska Samfundet).

- Wrightson, Charlotte Amala (born 1958). Ordained as a Zen priest in 1999. Sanctioned to teach in 2004. Kjolhede gave her Dharma Transmission in Feb 2012. Teacher at the Auckland Zen Center, New Zealand.

- Kjolhede, Sonja Sunya. Teacher at the Windhorse Zen Community, near Asheville, NC. Teacher at the Polish affiliate center (established by D. Gifford) of the Rochester Zen Center. Sister of Peter Kjolhede, wife of Lawson Sachter.

- Low, Albert (1928–2016). Teacher at the Montreal Zen Center.

- Sachter, Lawson David. Teacher at the Windhorse Zen Community, near Asheville, NC and spiritual director of the Clear Water Zen Center in Florida. Husband of Sonja Kjolhede.

Two students ended their formal affiliation with Philip Kapleau, establishing independent teaching-careers:[3]

- Packer, Toni (1927–2013) Teacher at Springwater Center (formerly named Genesee Valley Zen Center), Rochester.

- Clarke, Richard (born 31 January, 1933) From 1967 to 1980 a student of Philip Kapleau, but neither ordained by P. Kapleau nor sanctioned by him to teach. Teacher at the Living Dharma Center, Amherst, MA and Coventry, CT

Bibliography

[edit]- Awakening to Zen (New York: Scribner, 1997) ISBN 0-684-82973-8

- Straight to the Heart of Zen (Boston: Shambhala, 2001) ISBN 1-57062-593-X

- The Three Pillars of Zen (New York: Anchor Books, 2000) ISBN 0-385-26093-8

- The Wheel of Death (London: George Allen & Unwin LTD, 1972) ISBN 0-04-294074-5

- The Zen of Living and Dying: A Practical and Spiritual Guide (Boston: Shambhala, 1998) ISBN 1-57062-198-5

- To Cherish All Life: A Buddhist Case for Becoming Vegetarian (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1982) ISBN 0-940306-00-X

- Zen: Dawn in the West (Garden City, N.Y.: Anchor Press, 1979) ISBN 0-385-14273-0

- Zen: Merging of East and West (New York: Anchor Books, 1989) ISBN 0-385-26104-7

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c Ford p. 154

- ^ a b Ford p. 155

- ^ a b c Sanbo Kyodan: Harada-Yasutani School of Zen Buddhism and its Teachers

- ^ Albert Stunkard, "Philip Kapleau’s First Encounter with Zen", (Chapter 1) in Zen Teaching, Zen Practice: Philip Kapleau And The Three Pillars Of Zen, Weatherhill 2000, edited by Kenneth Kraft; ISBN 978-0834804401.

- ^ Yasutani p. XXVI

- ^ Yasutani p. XXV

- ^ "Zen Teaching, Zen Practice: Philip Kapleau and The Three Pillars of Zen". thezensite. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

First published in 1965, it has not been out of print ever since, has been translated into ten languages and, perhaps most importantly, still inspires newcomers to take up the practice of Zen Buddhism.

- ^ Ford p. 153

- ^ "Wayback Machine" (PDF). web.archive.org. Retrieved 2024-11-18.

- ^ "Wider Sangha - Rochester Zen Center". Retrieved 2024-12-05.

- ^ Sharf, Robert, H. (1995). "Sanbokyodan. Zen and the Way of the New Religions". Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. 22 (3–4): 446. doi:10.18874/jjrs.22.3-4.1995.417-458.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Wayback Machine" (PDF). web.archive.org. Retrieved 2024-12-05.

- ^ Ford p. 156

- ^ King, Sallie B. (1983). "Recent Dissertations in Religion". Religious Studies Review. 9 (2): 196–199. doi:10.1111/j.1748-0922.1983.tb00266.x.

- ^ "Chapin Mill Grounds - Rochester Zen Center". Retrieved 2024-11-18.

- ^ "Cloud-Water Sangha - Rochester Zen Center". Retrieved 2024-10-25.

References

[edit]- Ford, James Ishmael (2006). Zen Master Who?: A Guide to the People and Stories of Zen. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-509-8.

- Prebish, Charles S. (1999). Luminous Passage: The Practice and Study of Buddhism in America. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21697-0.

Philip Kapleau.

- Yasutani, Hakuun (1996). Flowers Fall: A Commentary on Zen Master Dogen's Genjokoan. Shambala. ISBN 978-1570626746.

- Nhat Hanh, Thich (1974). Zen Keys. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-47561-6.

- Kraft, Kenneth (2000). Zen Teaching, Zen Practice. Weatherhill. ISBN 86-7348-235-6.