The Princess on the Glass Hill

| The Princess on the Glass Hill | |

|---|---|

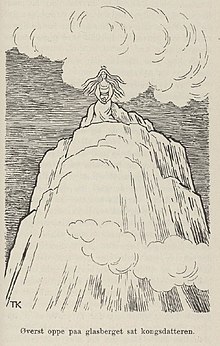

The princess sits atop the steep glass hill. Illustration from Barne-Eventyr (1915). | |

| Folk tale | |

| Name | The Princess on the Glass Hill |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 530 (The Princess on the Glass Hill) |

| Country | Norway |

| Published in | Norske Folkeeventyr, by Asbjornsen and Moe |

| Related | |

"The Princess on the Glass Hill" or "The Maiden on the Glass Mountain"[1] (Norwegian: Jomfruen på glassberget) is a Norwegian fairy tale collected by Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe in Norske Folkeeventyr.[2] It recounts how the youngest son of three obtains a magical horse and uses it to win the princess.

It is Aarne–Thompson type 530, which is named after it: the princess on the glass mountain. It is a popular type of tale, although the feats that the hero must perform in the second part, having obtaining the magical horse in the first, vary greatly.[3]

Synopsis

[edit]

A farmer's haymeadow was eaten every year on the Eve of the Feast of St. John the Baptist, also Midsummer. He set his sons, one by one, to guard it, but the older two were frightened off by an earthquake. The third, Boots also called Cinderlad, was despised by his brothers, who jeered at him for always sitting in the ashes, but he went the third year and stayed through three earthquakes. At the end, he heard a horse and went outside to catch it eating the grass. Next to it was a saddle, bridle, and full suit of armor, all in brass. He threw the steel from his tinderbox over it, which tamed it. When he returned home, he denied that anything had happened. The next year, the equipment for the horse was in silver, and the year after that, in gold.

The king of that country had a beautiful daughter and had decreed that whoever would marry her must climb a glass mountain to win her. She sat on the mountain with three golden apples in her lap; whoever took them would marry her and get half the kingdom.

The day of the trial, Boots's brothers refused to take him, but when the knights and princes had all failed, a knight appeared, whose equipment was brass. The princess was much taken with him, and when he rode one-third of the way up and turned to go back, she threw an apple to him. He took the apple and rode off too quickly to be seen. The next trial, he went in the equipment of silver and rode two-thirds of the way, and the princess threw the second apple to him. The third trial, he went in the equipment of gold, rode all the way, and took the third apple, but still rode off before anyone could catch him.

The king ordered everyone to appear, and in time Boots' two brothers came, and the king asked if there was anyone else. His brothers said that he sat in the ashes all three trials, but the king sent for him, and when questioned, Boots produced the apples, and therefore the king married his daughter to him and gave him half the kingdom.

Motifs

[edit]Origins

[edit]It has been suggested by scholarship (e.g., Carl von Sydow,[4] Hasan M. El-Shamy,[5] Emmanuel Cosquin,[6] Kurt Ranke)[7] that the origins of the tale type may have been first recorded in Ancient Egyptian literature, in The Tale of the Doomed Prince, wherein a prince needs to reach the princess's window by climbing a very tall tower.[8][9][10]

Researcher Inger Margrethe Boberg, in her study of the tale type through the use of the historic-geographic method, argued that the tale type must have originated with an equestrian people. Since variants are found among Germanic, Slavic, Indian, and Romano-Celtic peoples, and the main type (the princess sitting on the Glass Mountain) is distributed throughout Northern, Eastern and Central Europe, Boberg concluded that tale "came from the ages of Indo-European community". She also suggested that Finnish variants derived in part from Sweden and in part from Russia, variants among the Sámi originated from Norway, and Hungarian tales came from their neighbours.[11]

Professor John Th. Honti, in an opposite view from that of Boberg's, observed that she did not seem to be aware of the Ancient Egyptian story of The Tale of the Doomed Prince. According to Honti, the setting of the engagement challenge, the country of Naharanna or Nahrin, in ancient Syria, was famed for its high-towered constructions - and excavations give support to this claim.[12]

Another hypothesis was developed by Kaarle Krohn. In his Übersicht über einige Resultate der Märchenforschung, Krohn argued for a migration of the narrative from India, through Asia Minor and into Europe, until reaching Western Europe.[13][14]

Ossetian-Russian folklorist Grigory A. Dzagurov formulated a hypothesis that the versions with the tower developed in a southern region (possibly the Caucasus), migrated northwards via Russia and merged in Finland with the motif of the glass mountain - a motif that, to him, appears very late and seems to be geographically limited.[15]

The horse helper

[edit]The Aarne–Thompson–Uther tales types ATU 530, 531 (The Clever Horse) and 533 (The Speaking Horsehead) fall under the umbrella of Supernatural Helper in the folk/fairy tale index and pertain to a cycle of stories in which a magical horse helps the hero or heroine by giving advice and/or instructing him/her.[16]

Structure of the tale

[edit]

Scholarship recognizes that the tale can be divided in two parts: (1) the method of acquisition of the magical horse; and (2) the rescue of the princess (the Glass Mountain Challenge).[17][18]

Ashlad, the foolish hero

[edit]Folklorists Johannes Bolte, Jiří Polívka and Marian Roalfe Cox named the main character of the tale type männlichen Aschenbrödel (a Male Cinderella), because the protagonist usually sleeps in the ashes, or plays in ashes and soot.[19][20] Alternatively, he is usually found at home by the stove, in shabby and dirty clothes, and is often mocked by his family for this strange behaviour.[21] As such, English translations commonly name the protagonist "Ashboy", "Ashlad", "Cinderface" or some variation thereof. He appears as lazy and foolish at first, but as the story progresses, develops more heroic attributes.[22]

The acquisition of the horses

[edit]The motif of the brothers' vigil at a garden or meadow and the failure of the elder ones hark back to the ATU 550, The Golden Bird. Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald noted in Ehstnische Mährchen (1869) that in several variants the youngest of three brothers, often called stupid or simpleton, is helped by his father's spirit when he is told to hold a vigil for three nights.[23]

August Leskien acknowledged that the "numerous" Slavic variants "almost universally begin" with the father's dying wish for his sons to hold a vigil for his coffin or dead body at night.[24] The vigil on the grave is also considered to be "the most popular trial" in Lithuanian variants.[25]

The foolish youngest son is speculated by professor Gražina Skabeikytė-Kazlauskienė to have some connection with the ancestors, since it is by respecting his father's dying wish that he is granted the magical horses by his spirit.[26]

In these tales, either the hero receives one single horse, or tames/captures three horses of different colors: copper, silver and gold; of white, black and red;[27] or, as in Latvian variants, of silver, gold and diamond color.[28] Professor Heda Jason suggests that their different color gradient indicates the magical power of each horse.[29]

Hungarian scholars János Berze Nágy and Linda Dégh saw a possible connection between the copper, silver and golden horses of the Hungarian variants of type 530 with the táltos horse of Hungarian mythology. The same coloured horses appear in the context of another tale type: former type AaTh 468, "The Tree that Reached up to the Sky".[30]

The Glass Mountain challenge

[edit]Some scholars, such as Clara Ströbe,[31] Emil Sommer (de)[32] and Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald,[33] noted that the tale of a princess on the Glass Mountain seemed to hark back to the Germanic legend of Brunhilde, who lay atop a mountain, inaccessible to most people.

In some variants, the princess is not located atop a Glass Mountain. Instead she is trapped or locked in a high-store tower.[34] The latter type seems more common to Eastern Europe, Russian and Finland.[35]

French comparativist Emmanuel Cosquin noted that the motif of the hero's ascension on the Glass Mountain, in Western variants, was parallel to the motif of jumping to the roof of a palace, present in Indian variants.[36]

Carl von Sydow detected three oikotypes: the Glass Mountain belongs to the Teutonic one; the Slavic one contains the high tower; and the Indian version shows a high palisade.[37][38]

Scholar Kurt Ranke noted that another ecotype of the ATU 530 developed in the "West European-Celtic Romance" area, where tellings replace the Glass Mountain for a tournament.[39]

In some variants, the tournament part is similar to Iron John (Iron Hans), where the prince (who was working as a gardener) wears an armor to take part in the contest and catch the apples the princess throws. Under this lens, the tale type (ATU 530) becomes contaminated with similar tale types about a horse: ATU 314, "Goldener"; ATU 502, "Wild Man as Helper" and former type[a] AaTh/AT 532, "I Don't Know" (The Helpful Horse).[40]

Variants

[edit]Scholarship states that that tale type is one of the most popular,[41] being found all over Europe,[42] "particularly northern and eastern".[43] The tale is also present in collections from the Causasus, the Near East,[44] Turkey and India.[42] Folklorist Erika Taube argued that the tale type seemed widespread among the Turkic peoples.[45]

Europe

[edit]Scandinavia

[edit]The tale is said to be popular in Scandinavian countries.[46]

G. A. Åberg collected a variant from Pyttis (Pyhtää), in Nyland, titled Om pojtjin som bläi djift me kuggns dótro ("The boy who married the princess") that begins with the vigil at the father's grave.[47] He also collected two dialectal variants, Prinsässan up glasbjärji[48] and Prinsässan upa glasbjärji.[49]

Anders Allardt collected a dialectal variant from Liljendal, titled Torparpojtjis tjénsten (Swedish: Torparpojkens tjänst), wherein the youth acquires three horses, one shod with steel, another with silver, and the third with golden. He later climbs the Glass Mountain.[50]

Finnish folklorist Oskar Hackman summarized some Finnish-Swedish variants in his publication Finlands svenska folkdiktning. In one variant from Vörå, a father shares his property with his two elder sons, while giving nothing to the youngest. However, the father asks his third son to hold a vigil on his grave. He does and is given three pipes, with which he summons three horses: the first shining like the moon, the second shimmering like the stars, and the third glowing like the sun. Meanwhile, the local king builds a glass tower and announces that, whoever jumps high to touch his daughter's hand, shall marry her.[51]

In another Finnish-Swedish variant, from Oravais, a rich lord asks his three sons to hold a vigil on his grave. The elder two sends the youngest in their stead, and the youngest receives three pipes from his father's spirit, which he uses to summon three horses: the first of a copper colour, the second of a silver colour, the third of a golden colour. The local king places his daughter atop a great mountain and sets a challenge for any suitor.[52]

Norway

[edit]Scholar Ørnulf Hodne, in his book The Types of the Norwegian Folktale, listed 33 Norwegian variants of type 530, Prinsessen på Glassberget ("Princess on Glass Hill").[53][54]

Sweden

[edit]Benjamin Thorpe, in his compilation of Scandinavian fairy tales, provided a Swedish version on his book and listed variants across Norwegian, German and Polish sources.[55]

Several other variants have been collected in Sweden such as The Princess and the Glass Mountain,[56] and Prinsessan uppå Glas-berget[57] ("The Princess on the Glass Mountain") (from South Smaland),[58] George Webbe Dasent also gave abridged summaries of four other variants: one from "Westmanland" (Västmanland), a second from "Upland" (Uppland), a third from "Gothland" (Götaland) and a last one from "West Gothland" (Västergötland).[59]

A version of the tale exists in a compilation of Swedish fairy tales, by Frithjuv Berg. In this story, a young prince is tricked into releasing a dwarf his father captured. The prince is exiled from the kingdom to another realm and finds work as a shepherd. In this realm, the princess wants to marry no one, but the knight who dares climb the Glass Mountain. The prince wants to beat the princess's challenge, and the dwarf, in gratitude, gives him a shining steel armor and gray horse, a gleaming silver armor and white horse, and, finally, a bright gold armor and gold-coloured horse.[60]

Swedish folktale collectors George Stephens and Gunnar Olof Hyltén-Cavallius listed at least two Swedish variants that begin with a "Wild Man" character (akin to Iron Hans).[61] They also gave an abridged summary of a version where the peasant hero finds three horses and three armors, in silver and golden color and the third gem-encrusted.[62]

Denmark

[edit]Denmark also attests its own versions: one by Jens Nielsen Kamp (Prinsessen paa Glasbjaerget),[63] and a second, by Svend Grundtvig, translated as The Bull and the Princess at the Glass Mountain, where the hero's helper was a bull, and later it is revealed the bull was the titular princess's brother.[64] In a third variant by Svend Grundtvig, Den sorte Hest ("The black horse"), Kristjan, the youngest brother, herds his sheep to a meadow in the forest and discovers a cave with a (white, red and black) horse, a (white, red and black) armor and (white, red and black) sword. Kristjan then uses the horses to reach the princess atop a Glass Mountain.[65]

In a variant collected by Evald Tang Kristensen, titled Prinsessen på glasbjærget, Perde, the youngest son of a farmer, receives a stick from a donor. Later, when he takes the pigs to graze, he sees a troll with three heads on the first night; a troll with six heads on the second night, and a troll with nine heads on the third night. Perde kills the trolls and discovers their hideout in the mountain: he finds a black horse and a copper armor, a brown horse with a silver armor and a golden horse with a golden armor. After he beats the challenge of the Glass Mountain, he asks the princess to find him on his father's farm.[66]

Faroe Islands

[edit]Faroese linguist Jakob Jakobsen listed four Faroese variants, grouped under the banner Øskudólgur ("Ash-lad") and compared it to the Scandinavian versions available at the time.[67][68]

Western Europe

[edit]Professor Maurits de Meyere listed one variant under the banner "Le Mont de Cristal", attested in Flanders fairy tale collections, in Belgium.[69]

In an Austrian variant, Der Aschentagger, Hansl holds a vigil at his father's grave in the churchyard for three nights and is rewarded for his efforts. Later, his brothers take part in the king's challenge: to climb a very steep hill in order to gain the hand of the princess.[70]

In a Swiss variant from Schams, Der Sohn, der drei Nächte am Grab des Vaters wacht ("Of the Son, who watches his father's grave for three nights"), the youngest of three brothers - also the most foolish - fulfills his father's last wish for their sons to watch over his grave for three nights. He is rewarded by his father's spirit with three bridles and three splendid horses. Later, he uses the horses to beat the king's contest: to jump so high as to reach the princess in the tower for a kiss.[71]

The tale type reportedly exists in 66 versions in Ireland.[72]

France

[edit]Scholarship acknowledges that the tale type is one of the least or barely attested types in France and in Occitania.[73] It has been suggested that the region of Montiers-sur-Saulx was "the furthest extension" of the geographical reach of the tale type.[74]

Germany

[edit]

Kurt Ranke stated that the tale type was "very popular in Germany", and reported more than 60 variants.[75]

Ludwig Bechstein recorded a similar tale in Germany, titled Hirsedieb ("The Millet-Thief") (de), in his book of German fairy tales.[76] This version was translated as The Thief in the Millet and published in 1872.[77] Benjamin Thorpe also translated the tale, with the name Millet-Thief and indicated its origin as North Germany.[78]

Professor Hans-Jorg Uther classifies German tale Old Rinkrank, collected by the Brothers Grimm (KHM 196), as a variant of the tale type.[79] The story involves a king that builds a glass mountain and puts his daughter atop it, setting a challenge for any potential suitors.

Germanist Emil Sommer (de) collected another German variant, from Gutenberg, titled Der dumme Wirrschopf: the youngest brother discovers that a small grey man on a horse has been stealing his father's haystacks for years, but he spares the creature's life and gains three horses (in brown, white and black colors). The king then sets a challenge for all brave knights: to rescue his daughter, trapped at the top of the glass mountain.[80]

In a variant collected from Oldenburg by jurist Ludwig Strackerjan (de), Der Glasberg, the three sons of a farmer, Hinnerk, Klaus and Jan (the youngest and the most stupid), try to discover who or what has been stealing their father's straw from the barn. Only Jan is successful: he follows a giant into a secret cave and finds three armors and three horses.[81]

Heinrich Pröhle collected two variants about a "Männchen" (a small man) that gives the farmer's son the magnificent horses with which to beat the king's challenges: in the first variant, the farmer's son uses the horses to fetch three wreaths the princess throws, and later she has a tall wall built for him to fail.[82] In the second variant, a small man gives the youngest son a golden key; when the king announces the challenge of the Glass Mountain, the farmer's son uses three different getups: a silver armor on a white horse, a golden armor on a black horse and a gem-encrusted armor on the spotted horse.[83]

In a variant collected by medievalist Karl Bartsch from Mecklenburg, Der dumme Krischan, Fritz, Johan and Krischan are tasked with a midnight watch on their father's coffin, but only Krischan obeys, and is rewarded three horses (of a white, bay and black color, respectively).[84]

Johann Reinhard Bünker collected a variant from the Heanzisch dialect (Ta' Këinich mit 'n Prant'), where the father asks his sons to hold a vigil on his grave for three nights - each son on each night.[85]

A study of fifteen versions of the tale was published by Wilhelm Wisser, with the name Ritt auf den Glasberg. In some of the variants he collected, the hay thieves are giants, the horse itself or human robbers. In other versions, the ride up the Glass Mountain is to redeem the princess from a curse, or is replaced by a simple horse-riding contest with the magical horses the hero found.[86]

German philologist Karl Müllenhoff mentioned a variant from Dithmarschen where the hero, Dummhans, steals the eye of a one-eyed giant that has been stealing the crops. In return for the eye, the giant gives Dummhans three sets of armor and three horses in order to climb the Glass Mountain.[87] In another variant he collected, Das Märchen vom Kupferberg, Silberberg und Goldberg, Hans works as a king's hare herder and, on three occasions, finds a (copper, silver, gold) sword, a horse with a (copper, silver, gold) bridle and a dog with a (copper, silver, gold) collar.[88]

Josef Haltrich (de) collected a variant from the Transylvanian Saxons, titled Der Wunderbaum ("The Wonderful Tree"): a shepherd boy, while herding his sheep to graze in the fields, sees a tall tree reaching to the heavens. He decided to climb up the tree and arrives at a copper kingdom, then a silver kingdom and finally a golden kingdom. In each of the kingdoms, there is a pool, where he dips his feet, hands and hair, and takes a twig from each kingdom. He climbs downs the tree and cannot see his sheep, so he travels to another realm. The king of this realm sets a challenge of the Glass Mountain for all potential suitors of his daughter.[89]

Professor Wilhelm Wisser collected a "Plattdeutsche" (Low German) variant titled Simson, tu dich auf!. The story begins when a father's three sons vow to keep watch on their garden, but only the youngest, dumb Hans, is successful. Hans discovers that three giants come in the night and retreat to a cave in the mountain by reciting an incantation "Simson, tu dich auf!" (akin to "Open, Sesame!"). Hans kills the giants, opens the cave and discovers magical horses. Later, the king establishes the challenge of the Glass Mountain ("glåsern Barg").[90]

In a variant from Flensberg, Knæsben Askfis, a farmer's three sons, Pe'r, Poul and Knaesben Askfis try to discover the hay thief, by hiding in a haystack. Knaesben Askfis hides in a haystack and is carried by the thief to a castle. He jumps out of the haystack and kills the thief. He also discovers in the castle three horses, of black, gray and white colors. Later the king sends his daughter to a glass mountain with three golden apples, to await for her future husband.[91]

Some variants from Hessen were collected, in fragmented and in complete form.[92]

Professor Alfred Cammann (de) collected a "West Prussian" variant, "Der gläserne Berg", wherein the king, after his wife's death, erects the Glass Mountain and sends his daughter there. Meanwhile, a farmer's three sons are sent to guard their fields, when a mysterious old man appears to each son and asks for a bit of food. The older sons insult the man and their food is turned into excrement; the youngest shares his food and the man alerts him about the magical horses that come in the night.[93]

Otto Knoop collected a German-language variant from the historical region of the Hinterpommern (Farther Pomerania), named Der dumme Hans. Hans, the youngest and foolish son, is paid talers by his brothers to go in their place for the night vigil for their father's corpse in the barn. Hans gains three whistles, of silver, golden and diamond colors, from his father's spirit. Later, he summons the horses to climb the Glass Mountain.[94]

Eastern Europe

[edit]In the Bosnian fairy tale Die Pferde der Wilen ("The Horse of the Vilas"), the youngest of three brothers stands guard in a meadow and captures three wild horses, respectively, of a white, a black and a reddish-brown color. With them, he beats the Sultan's challenges and gains the Sultan's daughters as wives for him and his brothers.[95]

In a Romanian variant, Der Gänsehirt ("The Gooseherd"), the youth, as a baby, was lulled by a nanny that whispered that he would grow up to marry the king's daughter. Years later, the boy intends to make it a reality. He goes to his three pastor godfathers, and the second gives him three feathers (copper, silver and gold) to summon three horses (copper, silver and gold) to climb up the Glass Mountain. He uses the horses to reach the kingdom located atop the glass mountain to woo the king's daughter.[96]

In the Croatian tale Vilen weiden einen Hirseacker ab, a farmer plants fields of millet, but on some nights the entire crop is destroyed by something. He orders his sons to stand guard, but only the youngest is successful: he captures the horse that has been eating the millet. Suddenly, a vila appears and gives him a copper bridle, a silver bridle and a golden bridle. Later, the king announces that whoever fetches a golden apple from the palace's roof shall gain his daughter for wife.[97]

Poland

[edit]The tale type is said to be one of the most frequent in Polish tradition,[98] with several variants grouped under the banner Szklanna Góra (The Glass Mountain),[99][100][101] which is the name of the tale type in the Polish tale corpus.[102]

Polish ethnographer Oskar Kolberg, in his extensive collection of Polish folktales, compiled several variants: O trzech braciach rycerzach ("About three knightly brothers"),[103] O głupim kominiarzu,[104] O głupim z trzech braci ("About the foolish of the three brothers"),[105] Klechda.[106]

In a Masurian (Poland) tale, Der Ritt in das vierte Stockwerk ("The Ride to the Fourth Floor"), the youngest son of a farmer holds a vigil on his father's grave, receives a magical horse and tries to beat the King's challenge: to find the princess in the fourth floor of the castle.[107]

Swedish folktale collectors George Stephens and Gunnar Olof Hyltén-Cavallius listed a Polish variant collected by Woycicki, named Der Glasberg ("The Glass Mountain").[108]

In the Polish version O Jasiu Głuptasiu, wieszczym Siwku Złotogrzywku i Śwince Perłosypce ("About foolish Jasiu, the prophetic Siwku with Golden-Mane, the Golden-Beaked Duck and the Swine with Pearls"), foolish Jasiu holds a vigil for his father's coffin and his spirit teaches him a spell to summon the marvellous Sivko horse, the golden-beaked duck and a swine with pearls. The foolish boy uses the horse to grab the princess's ring from a tall pole. Later, after Jasiu and the princess are married, his brothers insist that their younger brother should find the duck and the swine and present them to the king.[109]

In the Polish-Gypsy version Tale of a Foolish Brother and of a Wonderful Bush, collected by Francis Hindes Groome, the youngest son, a foolish boy, beats a bush with a stick and summons a fairy who grants him a silver horse, a golden horse and a diamond horse. In the second part of the tale, the foolish boy dresses up as a prince and defeats an invading army.[110]

Polish ethnographer Stanisław Chełchowski collected a variant from Przasnysz, titled O Trzech Braciach ("About Three Brothers"), wherein the youngest holds a vigil for his father and receives a cane. With the cane, he summons the horses to reach the princess on the second floor on the castle. Later, he uses the cane to summon an army to repel an enemy invasion.[111]

Polish ethnographer Stanisław Ciszewski (pl) collected a variant from Szczodrkowice, titled O dwóch braciach mądrych a trzecim głupim, który wjechał na szklanną górę po królewnę i ożenił się z nią ("About two smart brothers and a foolish one, who climbs the Glass Mountain and marries the princess"). The youngest brother receives a silver, a golden and a diamond horse from his father's spirit after the vigil on his grave.[112]

Bulgaria

[edit]The tale type is also present in the Bulgarian tale corpus, with the title "Келеш с чудесен кон спечелва царската дъщеря" ("The Boy with Wonderful Horses Wins the Tsar's Daughter").[113]

Seventeen variants have also been collected in Bulgaria, some naming the hero Ash-boy or a variation thereof. In one Pomak tale, the hero Pepelífchono receives a white, a black and a red horse and uses them to win the king's daughters for himself and his brothers.[114]

The title of the Bulgarian tale "Най-Малкият брат и трите коня" (Nay-Malkiyat brat i tritye konya; "The Youngest Brother and the Three Horses") attests the presence of the three horses, akin to other variants.[115][116]

In the tale Drei Brüder ("Three Brothers"), the youngest son, mockingly called Grindkopf, tames a horse that has been ruining his father's fields and receives a tuft of white, red and black hair. He uses the hair to summon three horses in white, red and black color to jump over a large ditch three times in order to reach each of the king's daughters. In the second part of the tale, after his marriage to the youngest princess, Grindkopf moves to a small house near the palace.[117]

Slovakia

[edit]Professors Viera Gasparíková and Jana Pacálová state that the tale type is very popular in Slovakia, with "numerous variants [početné slovenské varianty]" collected.[118]

In the Slovak variant Popelvár špatná tvár ("Ugly-faced Ashface"), first collected by Pavol Dobšinský and later published by literary historian Michal Chrástek (sk), the youngest son, a foolish prince mockingly named "Popelvár špatná tvár" by his brothers, stands guard in his father's meadow of soft silk. The youth is the only one kind enough to share his food with a little mouse, who gives him a bridle to tame three ferocious horses that have been trampling the meadow. Some time later, the queen plants a golden egg, a golden ring and a golden crown inside a golden towel, upon a high hill, and announces that she will marry the man who is able to get the three items. Popelvár špatná tvár tries his luck with the tamed horses, of copper, silver and golden color.[119]

In a second variant by Pavol Dobšinský, Popelvár – Hnusná tvár ("Ashface - ugly-face"), a farmer orders his three sons to guard their crop of oats from whatever is coming at night. Popelvár and his brothers have a meal before their duty, and his brothers soon fall asleep, leaving Popelvár the only one awake. The youth climbs up a tree to await for something's arrival. The "something" is three horses, of golden, silver and copper color, which Popelvár tames and receives a bridle of each respective color. Later, the king sets a challenge: he will give his daughter's hand in marriage for the one who can jump very high and take out a ring, an apple and the golden handkerchief from the castle's highest arch.[120]

Slovak author Ján Kollár published a variant titled Tátoš a biela Kňažná ("The Tátos Horse and the White Princess"), wherein it is the princess who sets the engagement challenge for her suitor: she puts a sword, an apple and a little flag on the highest tower for anyone brave enough to jump very high and obtain them.[121] Despite the unusual form, the tale is still classified as AT 530, or "Neznámy rytier sa na zázračných koňoch preteká o princeznú" ("The Mysterious Rider reaches the Princess on Wonderful Horses").[122]

Czech Republic

[edit]In a Moravian tale, Mr. Cluck, the titular Mr. Cluck (actually, the devil) gives Hans a black horse and a suit of armor, a silver armor with a brown horse and a white horse with another suit of armor. Hans uses the horses to beat the king's three tasks.[123]

In another Moravian tale, Jak se pasák stal králem ("How the herdsman became king"), the herdsman is warned not to take the sheep to graze on a certain meadow, where three giants are said to roam. He shared his food with an old lady by the well and receives a stick that turns someone into dust. The herdsman uses the stick to kill the giants and obtains three keys to open three different doors, of copper, silver and golden colours. Then the king announces a challenge for all brave knights: he hides three treasures (a golden sword, his sceptre and his crown) atop a Glass Mountain, and whoever brings them back, shall marry his daughter and inherit the kingdom. The herdsman opens each door with a key he found and mounts a splendid horse with golden color and diamond hooves.[124]

In the variant O mramorovém kopci ("The Marble Mountain"), the youngest son, foolish Honza, watches his father's haystacks to protect them from a thief. Later, he sees that a bird is the culprit and latches onto the animal to capture it. Honza is transported to a castle where he finds a talking horse. When the king announces that he will give his daughter to anyone who scales the marble mountain. Honza seizes the opportunity, rides the talking horse and succeeds three times, in silver, golden and diamond armors.[125]

In the Moravian tale Janíček s voničkou ("Janicek with the perfume"), Janicek, a prince, dresses in peasant attire and travels to a king's castle. On his way, he gives alms to four beggars and is rewarded with four magical items: a musket, a club, a whistle and a bag. He employs himself as a shepherd in the king's country. One day, he herds the sheep to the forest and sees a castle in the distance. He enters the castle and faces a giant, killing him with the musket. The next day and the day after, he kills the giant's other brothers and takes control of the castle. Soon after, he opens a closet and two servants appear. Janicek also takes three fragrant flowers from the garden and gives to the princess. Later, once each month, a procession of princes pass under the princess's balcony, and each time Janicek grabs her handkerchief when riding a white horse with silver bridle, a red horse with golden bridle, and a black horse with diamond ornaments.[126]

Author Božena Němcová published a variant titled Diwotworný meč, wherein the prince acquires a magical sword and is helped by a talking horse. Some time later, the prince travels to a kingdom where the king built a dam on a huge circle, placing his daughter upon it, and promised his daughter for anyone who jumped very high and got the gifts his daughter held with her. The prince is successful and the tale continues as ATU 314, "The Goldener" (the prince as gardener), after the horse instructs the prince to disguise himself as a lame and ugly gardener.[127]

Czech author Václav Tille (writing under pseudonym Václav Říha) published the tale Tátoš: a man's three sons are tasked with guarding his fields. On the first two nights, a fox approaches the older brothers and asks for a bit of food to eat. Both shoo it away. On the third night, the youngest son, Jan, shares a bit of food with the fox and it warns him of the Tátoš (a powerful and magical horse) that comes in the night. Jan tames the horse and uses it to beat the king's challenge: to jump very high and reach the three princesses sat atop a "gallery" ornate with diamonds and gems. In the second part of the tale (type ATU 530A), the king sends his new sons-in-law after a cooper pine tree with silver branches and golden pines, and a jumping goat with golden horns and a white beard.[128]

Serbia

[edit]In a Serbian fairy tale, The Three Brothers, of considerable complexity and length, after their father dies, three brothers need to decide what to do with his properties. However, for two years, the farm's haystacks are devoured by winged horses led by fairies. On the third year, the eldest brother tames one of the horses and gets a piece of hair to summon the winged steed, should the need arise. When the brothers go their separate ways, the eldest one arrives at three different kingdoms where each king sets a horse-racing contest: any competitor should ride their horse and jump to reach the princess on the other side of a wide and deep ditch.[129]

In a second Serbian tale, collected by Elodie Lawton Mijatovich, The Dream of the King's Son, the youngest prince reveals his prophetic dream: his brothers, his mother and his father would serve him in the future. The king promptly expels him from home. He later finds work with an old man, who, in reality, want to kill the prince. The youth escapes with a talking golden horse and flees to another kingdom, where the king announces that any suitor should jump over a large ditch to reach the princess.[130]

Slovenia

[edit]In a Slovene variant titled Trije kmečki sinovi ("The Three Peasant Sons"), three sons volunteer to guard their father's crops from whatever is destroying the fields. The first two brothers meet a little mouse that asks for food and rebuff it, but the third brother, who "played in ashes and straw" shares his food. As a reward, the little mouse informs the boy about the horse and gives him a bridle: a copper bridle for the copper horse in the first night, a silver bridle for the silver horse in the second night, and finally a golden bridle for the golden horse in the third night. The boy tames the wild horses and receives a stick to summon them. Soon after, the king issues a proclamation that whoever climbs the tall tower on the high mountain and grab the golden ball shall marry the princess. This tale was collected in Porabje (Rába Valley), by Károly Krajczár (Karel Krajcar), from an old storyteller named Tek Pista (hu).[131][132]

In a tale from Prekmurje, Pepelko, a peasant couple has three sons, the older two help the father in the fields and the third helps his mother in the kitchen, which is why he is always covered in soot and ashes. When the mother dies, she asks for a hazelnut tree to be planted on her grave. Time passes, and the king decided that his daughter must marry. But she is too stubborn, for she will only marry the man who can reach her balcony by jumping and take her ribbon off her hair. The three brothers want to try his luck, but Pepelko cracks a hazelnut from the tree and finds a horse and garments. He wears the fine clothes and accomplishes the impossible task. The princess becomes enamoured of the mysterious stranger and repeats the challenge two other times: to take her golden necklace from her neck, and to allow her to put a ring on their finger as soon as they reach her.[133][134]

In a Slovenian tale translated into Russian with the title "Стеклянный мост" ("The Glass Bridge"), a commoner has three sons, the elder two smart and the youngest called Zapechnik ("the one that stays on the pech' [oven]"), for he is lazy and stays on the pech' all day. On his deathbed, the man asks his three sons to come to his grave at night in the cemetery for their inheritance. The man dies. Soon after, the elder two, too afraid to go visit to their father's grave, sends their youngest in their stead. Their father's spirit appears on each night and gives Zapechnik a nut, which he hides in the cemetery. Later, the king prepares a suitor selection test for his daughter, the princess: he commissions a glass bridge to be built, and any suitor must jump over it to win the princess's hand. Zapechnik goes back to the cemetery to crack open each nut: inside, a suit of armor and a horse, which he uses to beat the challenge.[135]

Mari people

[edit]In a tale from the Mari people titled "Конь с серебряной гривой" ("The Horse with the Silver Mane"), a beautiful princess wants to get married, so she sets a suitor contest. Meanwhile, a father on his deathbed leaves divides his properties among his three sons and asks them to light 40 candles on his grave for three nights. The two elder brothers buy the candles, but are too afraid to visit his grave at night. The youngest son, named Kori, fulfills his wish and, on the third night, a white winged horse with silver mane appears to him, thanks him for his filial devotion, and gives him three tufts of hair. Kori returns from the vigil and learns that the princess will only marry the bravest and most agile suitor. The brothers go to compete, and Kori summons the horse, named Argamak, to ride him and beat the princess's challenge: to touch a kerchief fixed on a huge poplar, and to run and jump into the princess's verandah to steal the ring from her finger.[136]

Kalmyk people

[edit]Hungarian Mongolist Ágnes Birtalan translated the tales collected by linguist Gábor Bálint in the 19th century from Kalmyk sources. In the eighth tale of his collection, named Ačit köwǖn ("The benefaction of the son") or Öwgnǟ γurwn köwǖn ("The old man’s three sons") by Birtalan, after his wife dies, an old man marries his two daughters to two yellow giants and orders his three sons to hold a vigil on his grave, one on each night. The elder brothers send their youngest, who is rewarded by his father's spirit with three horses: a yellow brown horse on the first night, a black brown horse on the second night, and a blue grey horse on the third. Later, the king sets a challenge: he will marry his three daughters to any suitor who can jump on a horse and steal an apple from the king's three daughters, sat on a high tree. The youngest brother accomplishes this and marries the youngest princess. However, his wife is kidnapped by a yellow giant and later he has to find another horse to get her back.[137]

Komi people

[edit]Linguist Paul Ariste collected two variants from the Komi people. In the first one, a poor couple have four sons, the youngest named Ivan the Fool. When the man notices their wheat fields are being trampled every night, and orders his sons to keep watch at night. The three elders pretend to go to the fields, and lie to their father that they did. When it is Ivan's turn, he discovers a white horse that appears at midnight. He approaches the horse and captures it. In return, the white horse says he can help Ivan and departs. In the same kingdom, a Tsar sets an engagement challenge for his daughter's suitors: he ties a golden ring to a church cross, and whoever gets it, shall marry the princess. Ivan the Fool summons the white horse and rides it to the church, succeeding in the third time.[138]

In another variant collected by Paul Ariste and titled Once there was an old farmer, a farmer has three sons, Ivan, Vasilyi and Peder (Fedor). On his deathbed, the man asks his three sons to hold a vigil on his grave for three nights, one on each night. The two elder brothers send Peder on the first two nights, and their father's spirit gifts him with a black horse in the first night and a grey horse in the second. Peder goes in the last night and is gifted with a chestnut horse. Some time later, a local Tsar sets a challenge: he places his daughter, Jelena Prekrasa, sat on the church cross, and whoever jumps high enough to get her golden ring from her finger, shall marry her.[139]

Mordvin people

[edit]In a tale from the Mordvin people titled "Три брата" ("Three Brothers"), a father has three sons, the elder two smart and the youngest a fool. On his deathbed, he asks his sons to watch over his grave for three nights. After he dies, the elder two sends their youngest brother in their place. Their father's spirit gives the third son a black hair (that summons a black horse with golden bridle) on the first night; on the second night, a gray-white hair (which summons a gray horse with silver bridle) and on the third night a red hair (which summons a pig and 12 piglets). In the kingdom, the king announces a challenge: his daughter, the princess, shall marry one that can jump to reach her highest room atop a tower and take out her golden ring.[140]

Chuvash people

[edit]In a tale from the Chuvash people titled "Кукша" ("Kuksha"; English: "Baldhead"), a man has three sons. The youngest, Ivan, is bald, so his brothers psuh him around and call him Kuksha. One day, on his deathbed, the man asks his sons to bury him and hold a vigil for three nights. After he dies, the eldest orders Kuksha to go in his place to their father's grave. Once there, the man's spirit appears to the boy, who confides in him about being mistreated by his elder brothers. His father's spirit tells him not to worry, and gives him a copper ring. On the next nights, Kuksha gets a silver ring and a golden one. Meanwhile, a local rich man sets a challenge: any of his daughter's suitor shall jump over a five-story building. Kuksha's brothers go to try their luck, and the boy uses the copper ring to summon a black horse. He rides it the first time, but cannot beat the challenge. The rich man tells the people to return in three years time for a repeat of the challenge. Again, Kuksha uses the silver ring to summon a gray horse, and, in a third attempt after another three years, uses the golden ring to summon a bay mount and win the challenge.[141]

Gagauz people

[edit]In a tale from the Gagauz people with the title "Кюллю-Пиперчу" ("Kyullyu Piperchu"), an old man finds his fields are being trampled every night, and his sons offer to stand guard on the fields. The elder two fail on their vigils, due to falling asleep, but the third son, the titular Piperchu (named so for always playing in the ashes) discovers the culprit: a "sea horse". Piperchu tames the horse and, in return, it allows the youth to pluck three hair from its tail, one black, one red (bay) and one gray. Later, Piperchu's brothers to town and go back home to tell their father the padishah announce a challenge: he will marry his daughter to anyone who can jump to the third floor of the palace to reach the princess's window. Piperchu's brothers go ahead of him, while he rides behind them on a lame donkey. After they are out of sight, Piperchu summons the black horse on his first attempt, a bay horse on the second, and a gray on the third attempt.[142]

Baltic Region

[edit]Estonia

[edit]The tale type is said to be quite popular in Estonia,[143] amounting to a number between 157 and 180 variants in Estonian archives.[144] According to Estonian folklorists, the introductory episode is the vigil on the father's grave, which rewards the third son with a copper, a silver and a golden horse that can be summoned with similarly coloured whistles or whips.[145]

An Estonian variant, The Princess who slept for seven years, translated by William Forsell Kirby, begins with the Snow White motif of the princess in a death-like sleep. Her glass coffin is placed atop a glass mountain by her father, the king, who promises her daughter to any knight that can climb the mountain. A peasant's youngest son stands vigil at his father's grave and is given a bronze horse by his father's spirit.[146] The tale was first collected by Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald in Ehstnische Mährchen (1869), with the title Wie eine Königstochter sieben Jahre geschlafen.[147] The tale was also translated as La Montagne de Verre by Xavier Marmier.[148]

Finland

[edit]Finnish author Eero Salmelainen collected a Finnish tale from Karelia originally titled Tuhkimo, which Emmy Schreck translated as Der Aschenhans. In this tale, the youngest son of a farmer, called Tuhkimo ("The One of the Ashes"), prays at his father's grave for three nights and is rewarded for his filial piety with a copper-bridled black horse, a silver-bridled "water-grey" horse and a golden-bridled snow-white horse. Tuhkimo (or Aschenhans) uses the horses to reach the king's daughter, atop the tallest tower.[149][150] This tale also merges with ATU 675,"The Lazy Boy" or "At the Pike's Behest".

In another Finnish variant collected by Salmelainen, Tytär kolmannessa linnan kerroksessa[151] or Das Mädchen im dritten Stockwerke der Hofburg ("The Girl in the Third Floor of the Castle"), a variant of the above,[152] the youngest son, Tuhkimo ("Aschenbrödel") visits his father's grave for three nights and receives a red horse with a "Sternblässe" (a star-like shape on its head), a gray horse with a "Mondblässe" (a moon-shaped patch on its head) and a black horse with a "Sonneblässe" (a sun-shaped mark). He uses them to reach the princess on the third store of the palace.[153]

In a tale collected by August von Löwis de Menar with the title Das Zauberroß ("The Magic Steed"), the dumb hero gets from the devil a magical horse that can make him a handsome knight. The youth, named Aschenhans, will try his luck when the king announces his daughter's hand in marriage for anyone who can reach her, inside a house atop a "hall three fathoms large".[154]

In a Finnish tale translated as Aschenputtel ("The Ash-Sitter"; "Male Cinderella"), a father has three sons, the youngest named Aschenputtel for he spends his time on the oven and wears a shirt dirtied with soot. One day, he notices that someone has been stealing the hay in their barn, and tasks his three sons to guard it. The elder two hide in the haystack and see some thieves, but decides to do nothing. The youngest, Aschenputtel, hides is a sack and waits for the thieves. The bag he is in is taken by the bandits; he springs out of the bag and hits one with a stick, while the others thieves kill each other in the fracas. Aschenputten goes to the thieves' hideout, kills an old woman there and finds armours and three steeds. Later, the king announces that whoever can climb a glass mountain to fetch the princess' portrait shall marry her. Aschenputtel rides the three horses he found at the hideout, each studded with diamond hooves, to beat the challenge.[155]

Sámi people

[edit]The tale type has also been collected from the Inari Sami. A variant was translated into English with the name The Poor Boy and the King's Daughter, where, after his father dies, the poor youngest son captures a golden horse and rescues the king's daughter from a mountain.[156]

In the Sámi tale The Three Brothers, a father's dying wish is for his sons to visit his grave for three nights, but only Ruöbba, the youngest, respects his last will. As such, his father's spirit grants him a cane to open a hidden storehouse with a horse and splendid garments. Then, the king announces his daughter is sitting atop a mountain and a knight brave enough should ride or jump and reach her to allow her to mark an imprint of her ring on the knight's flesh.[157] Its collectors acknowledged it as a variant of the Norwegian tale.[158]

Lithuania

[edit]According to Lithuanian folklorist Bronislava Kerbelyte, the tale type is reported to register 330 (three hundred and thirty) Lithuanian variants, under the banner The Princess on The Glass Mountain, with and without contamination from other tale types.[159] Another research indicates that the number is still high, but amounting to 254 (two hundred and fifty-four) variants.[160]

In some variants of the tale type, the hero tames three horses: in one version, the horse of the sun (saulės arklį), the horse of the moon (mėnesio arklį) and the horse of the star (žvaigždės arklį);[161] in another, three steeds with astronomical motifs on their bodies, and the first two are renamed "Sun-horse" and "Moon-horse".[162] In another Lithuanian variant, the foolish brother, while guarding the oat field, captures the third horse, which was "bright as the moon", and narrative explicitly refers to it as "Moon-horse" (mėnesio arkliuką).[163]

German professor Karl Plenzat (de) tabulated and classified some Lithuanian variants, originally collected in German language. In three of them, the hero finds three horses, of a silver, golden and diamond colors.[164]

In a Lithuanian tale, Little White Horse, the youngest of three brothers stands vigil at midnight on his father's barley field and captures a magical, flying steed of a white color.[165] This tale was also collected by August Leskien with the name Vom Dümmling und seinem Schimmelchen.[166]

Latvia

[edit]The work of Latvian folklorist Peteris Šmidts (lv), beginning with Latviešu pasakas un teikas ("Latvian folktales and fables") (1925-1937), recorded 77 variants of the tale type, plus another eleven in his annotations, all under the banner Ķēniņa meita glāžu kalnā ("The King's Daughter on the Mountain of Glass"). The tale is also said to record nearly 420 (four hundred and twenty) variants in Latvian archives.[167]

In a Latvian variant collected in 1877, "Братъ дуравъ и его звѣри помощники" ("The foolish brother and his animal helpers"), the youngest brother, taken as a fool by his brothers, uses a silver horse, a golden goat and a diamond horse to climb up the mountain and retrieve a handkerchief and a ring for the princess.[168] In another variant, the foolish brother rides a silver horse on the first day, a golden horse on the second day and a diamond horse on the third day.[169]

In another Latvian variant, "Братъ дуракъ и отцовская могила" ("The foolish brother and his father's grave"), the foolish brother is the only one to visit his father's grave at night. For his efforts, his father's spirit gives him two sticks with which he can summon a shining horse of gold and diamond colors.[170]

Professor Stefania Ulanowska (pl) published a variant collected from Latgale, originally in Latgalian, titled Ap div bruoli gudri, trešš duraks (Polish: O dwu braciach rozumnych, trzecim durniu; English: "About two smart brothers and the foolish third one"). In this version, the youngest brother visits his father's grave at midnight in his brothers' stead and his father's spirit gives him a copper, a silver and a golden horse. The father explicitly tells his son that he would have given the copper and the silver horses for his elder sons, had they come.[171]

In another variant, "Серебряный конь, золотой конь, алмазный конь" ("Silver Horse, Golden Horse, Diamond Horse"), a poor man, as his dying wish, asks his three sons to stand guard on his grave for three nights. The elder brothers feign sleep and the youngest, the most foolish of all three, fulfills his father's request. For his efforts, his father's spirit gives him three two-sided whistles in different colors: a silver, a golden and a diamond one. The father's spirit explains that if his son blows on one side of the whistle, the respective horse appears in garments of that color, and if he blows on the other side, the horse will be dismissed. Some time later, the king announces a challenge: he places his daughter on a glass mountain and promises her hand to anyone brave enough to climb it on horseback and take her ring as proof of their bravery. The youngest uses the horses on three days, each time reaching a bit higher than the last, and getting the princess's ring with the diamond horse. At the end of the tale, the foolish hero gives his brothers two of the magic whistles.[172]

In a Latvian variant from Aumeisteri, translated into Hungarian with the title A királykisasszony az üveghegyen ("The King's Daughter on the Glass Hill"), the foolish third brother holds a vigil on his father's grave for three nights and receives a silver whistle, a golden whistle, and a diamond whistle to summon three horses of these colours. He uses the horses to beat the king's challenge to climb the Glass Mountain.[173]

In another tale, The Princess on the Glass Mountain, a father asks his three sons to hold a vigil on his grave for three nights. After he dies, the elder two send the youngest brother, whom they consider a fool, in their place. Their father's spirit gives the foolish brother a silver whistle on the first night, a golden whistle on the second night, and a diamond whistle on the third night. Later, a king establishes a suitor test for his daughter: he commissions the building of a glass mountain, places the princess atop it and a diamond ring on her finger. The foolish brother, for three days, summons a silver horse, a golden horse and a diamond horse, climbs the glass mountain and wins the challenge.[174]

Southern Europe

[edit]Variants have been attested in Spain with the name The Horse of Seven Colors (Catalan: Es cavallet de set colors).[175]

In a Portuguese variant, As Três Nuvens ("The Three Clouds"), the youngest son of a rich farmer goes to investigate a seemingly haunted property that belongs to his father. He takes his guitar with him and, before he sleeps, hits some notes on the strings, an event that disenchants three fairy maidens in the form of clouds: a black one, a "parda" (brownish) and a white one. When the king announces three tournaments, the youth summons the fairies, which grant him the armors and the horses.[176]

A scholarly inquiry by Italian Istituto centrale per i beni sonori ed audiovisivi ("Central Institute of Sound and Audiovisual Heritage"), produced in the late 1960s and early 1970s, found two variants of the tale across Italian sources, under the name La Principessa sulla Montagna di Cristallo.[177]

Author Iuliu Traian Mera published a Romanian variant titled Cenuşotca ("[Male] Cinderella"). In this tale, an old man has three sons, the youngest mockingly named Cenuşotca, for he spends his days near the fireplace/oven and dresses in shabby clothes. One day, the man prepares to harvest his large crops, but, the next morning, everything is trampled over, as if a horse trotted through his fields. His elder sons decide to keep watch, each on each night, but they fall asleep and fail. The third night, Cenuşotca offers to watch over the fields and finds a wild horse. He jumps over the horse and manages to tame it. Recognizing Cenuşotca as its new master, the horse allows the youth to take three hairs of its mane, one in silver colour, the second of a golden colour, and the third of a diamond colour. Meanwhile, the local Imparatul Verde ("Green Emperor") sets a task for any suitor brave enough to marry his daughter: he ties a golden crown to a high flag pole on the castle walls, and any rider shall jump very high to take it off the flag pole. Cenuşotca summons three horses and makes three attempts to fetch the crown, the first with the silver horse and in silver clothes; the second with a gold horse and in golden clothes, and finally with a diamond horse and in diamond garments.[178]

Chechnya

[edit]In a variant from Chechnya, Die Drei Brüder ("The Three Brothers"), a father asks his three sons to hold a vigil for him for three nights, each son on each night. On the first two nights, the oldest and the middle brother do not stay at their father's grave for the whole night out of fear. On the final night, the youngest son completes the vigil and witnesses the arrival of three horses: a black, a red and a white one. The youth tames the three horses and gains three horsehairs from each one. Later, a sovereign with three daughters orders his slaves to dig a deep ditch and erect three high platforms.[179]

In another Chechen tale, translated as "Три брата" ("Three Brothers"), a father, sensing his approaching death, asks his three sons to build him a grave out of rock salt, and to visit the grave. The sons bury him and visit his resting place. The brothers notice that the tombstone is being chipped away, and decide to protect it during the night. The elder brother sleeps through his three nights vigil, so does the middle brother. As for the youngest, in the first night, a black mist descends near the grave, and the youngest attacks it; the mist becomes a black horse that he tames. In the second night, a white apparition becomes a gray horse, and in the third night, a red mist becomes a bay horse. The youth tames all three and is given one of their hairs in return. Some time later, the three brothers take part in a series of contests set by the prince: a racing contest; to get his daughter's ring from beneath a tree at the foot of Mount Kazbek; to get two falcons from a nest atop a high mountain; and to fetch a ram located in a deep well.[180] In another version of the tale, titled "Три брата, три облака, три волшебных коня и три княжеские дочери" ("Three Brothers, Three Clouds, Three Magical Horses and Three Princesses"), the youngest brother is named Ali; and the test of the falcons is to ride up the mountain to steal a feather from their nest.[181]

Caucasus Region

[edit]According to scholar K. S. Shakryl, tale type 530 appears in the Caucasus in combination with type 550 or type 552A.[182]

In an Avar language version collected by Anton Schiefner, Der schwarze Nart, the youngest prince heeds his father's request to pay his final respects on his grave for three nights. In the first night, the prince tames a "himmelfarbener Apfelschimmel" stallion ("a sky-coloured" gray horse); in the second, a red horse and in the third night a black steed. All animals give him a bit of horsehair to summon them. Later, the first horse is described as a "blue" ride, with blue ornaments, and he uses it to beat the challenge of the "King of the Occident": to jump very high and reach the princess on a tower.[183] Anton Schiefner also connected the tale to similar European variants of The Three Enchanted Princes, a folktype classified as ATU 552, "The Girls Who Married Animals".[184]

Philologist Adold Dirr published an Armenian variant, Das Feuerpferd ("The Fire-Horse"), extracted from his book on Eastern Armenian language.[185] The youngest brother tames the titular Fire-Horse and in return learns a command to summon it. Later, the king invites the entire kingdom for a banquet and a challenge: to reach his daughter on the highest tower on horseback.[186]

In a Kabardian tale translated into Russian as "Три брата" ("Three Brothers"), an old knyaz has three sons. On his deathbed, he asks his sons to hold a vigil on his grave for three nights, a son on each night. He is buried and the youngest is sent by his brothers to guard their father's grave. On the first night, a knight in red armor and bay horse tries to desecrate the father's grave, but the third son defeats the knight and takes his garments. On the second night, the same event happens, but with a white knight on a white horse, and on the third night, with a black knight on a black horse. Time passes; a rich knyaz announces a series of games and trials for his daughter's hand. The youth's older brothers join in the games and leave him home, but he rides one horse on each day of competitions: he rides the red horse and shoots an arrow at a high target; he rides the white horse and joins a horse-racing contest, and lastly the black horse to defeat a bull.[187]

Ossetian-Russian folklorist Grigory A. Dzagurov published a tale from the Ossetians with the title "Фунуктиз, младший из трех братьев" ("Funuktiz, the Youngest of Three Brothers"), three brothers live together, the youngest named Funuktiz, for he likes to play in the ashes. One day, they learn that their cereal crops near the forest are being trampled by a wild horse, and organize a watch. The elder two claim they will have the first turns, but sleep elsewhere. Finally, the youngest, Funuktiz goes himself one night and finds the wild horse; he approaches the animal and grabs it by its mane. The horse recognizes the youth a his new master and gives him a bridle. Later, an aldar has a beautiful daughter locked up in a tower for her whole life, and announces a challenge: whoever can reach the girl and steal the ring from her finger shall have her for wife. Funuktiz takes part in the challenge on the wild horse and, after two tries, he snatches her ring.[188]

Georgia

[edit]Georgian scholarship registers variants of type ATU 530, "Magic Horse", in Georgia, and notes that the type "contaminates" with type 552A, "Animals as Brothers-in-Law".[189] In the Georgian variants, the hero (the third and foolish brother) holds a vigil on his father's grave, gains the horse and jumps high to reach the princess on a tower.[190]

In a Georgian variant, sourced as Mingrelian, The Priest's Youngest Son, a father's dying wish is for his three sons to read the psalter over his grave, one son on each night. However, only the youngest son appears and is rewarded with three horses. He later rides the horses to jump very high in order to kiss the princess on the castle's balcony.[191]

Azerbaijan

[edit]Azerbaijani scholarship classifies tale type 530 in Azerbaijan as Azeri type 530, "Qəbir üstündə keşik çəkmə" ("Holding a vigil on the grave"): the youngest son holds a vigil on his father's grave and gains three horses which he uses to beat the king's challenge (either jumping over a ditch or jumping to reach the princess on a balcony).[192]

In an Azeri tale published by Azeri folklorist Hənəfi Zeynallı with the title "Мелик-Джамиль" ("Melik-Jamil"), a king is dying and as a last request asks his three sons, Melik-Achmed, Melik Jamshid and Melik-Jamil, to hold a vigil on his grave for three nights, and to marry their sisters to whoever passes by 40 days after his death. The youngest, Melik-Jamil, fulfills his father's wish and protects his grave against three assailants: one on a dark brown horse, the other on a white one and the third on a red. The prince steals the horses and uses them to win another king's trial: to jump over a large ditch to get his daughters. He gets the third one, but she is kidnapped by a man whose soul lies in an external place (type ATU 302, "Ogre's Heart in an Egg").[193]

Americas

[edit]United States

[edit]A variant named The Three Brothers was recorded from West Virginia by Ruth Ann Musick, which she identified as hailing from a Polish source (a man named John Novak).[194] The tale begins with the night vigil on the father's grave by the youngest son, who is awarded by his father's spirit with a switch, a magic ring and a magic horse. A neighbouring king has a daughter who lives on a glass hill, and the youth and their brothers decide to try their luck. Only the youth accomplishes it, with the help of a black horse, a roan coloured one and a white one.[195]

Richard Dorson collected a variant titled Cinders in Michigan, from a man named Frank Valín: the princess waits at the top of the glass mountain with her photograph, and the bashful Tuhkimo, with the help of an old man, rides horses with silver, golden and diamond shoes to scale the mountain.[196] He also collected a variant from a man named Joe Woods. In his tale, Crazy Johnny, or Marble Castle, the king builds a marble castle atop a great mountain to house his daughter. When she is 18 years old, she requests her father to issue a challenge: anyone who "can climb the back horse to the castle" will be her husband. Elsewhere, "a mile from the city", gullible Johnny observes ants carrying a silver ring. He takes it from them. He scrubs the ring a voice tells him it is his servant. When Johnny learns of the engagement challenge, he uses the ring to wish for a silver-, golden- and diamond-coloured horse and garments to beat the challenge. When he marries the princess, a neighbouring king issues a declaration of war. Johnny, once again, dons the splendid clothes and summons an army three times with ring. When the princess's father asks about his good-for-nothing son-in-law, Johnny plays up the foolish act by a pond full of frogs.[197]

A variant from New Mexico was collected by José Manuel Espinosa in the 1930s from a sixty-three-year-old Sixto Cháves, who lived in Vaughn, New Mexico. The tale was republished by Joe Hayes in 1998 with the title El caballo de siete colores ("The Horse of Seven Colors"). In this tale, three brothers move to another city and take up a job offer to hold a vigil on the prince's garden. The youngest brother discovers the horse of seven colors. In another city, the king promises to give their daughters in marriage to anyone who can snatch rings from the balcony of the palace.[198]

Latin America

[edit]Variants of the tale type ATU 530 are attested and widespread in Latin-American traditions with the name The Horse of Seven Colors.[199][200] Scholarship points to its presence in regions of Hispanic colonization.[201]

A variant was collected from the Qʼanjobʼal language and translated into English.[202]

Mexico

[edit]A variant was collected from Tepecano people in the state of Jalisco (Mexico) by J. Alden Mason titled Fresadiila and published in the Journal of American Folklore. Despite not following the tale type to the letter, the youth Fresadilla captures the "caballo con siete colores" and later takes part in a rodeo as a mysterious horseman, to the delight of the crowd and admiration of his clueless brothers.[203]

Puerto Rico

[edit]J. Alden Mason and Aurelio Espinosa collected some Puerto Rican variants grouped under the title El Caballo de Siete Colores ("The Horse of Seven Colors"). In 5 of these variants, the story begins with the night vigil on the father's fields by his three sons and the discovery of the culprit by the youngest son: a mysterious multicoloured horse. In another, El Caballo de Siete Colores, the youngest brother is saved by the multicoloured horse, and later rides the mount to grab a "sortija" (a ring) on the palace's balcony.[204]

Venezuela

[edit]Professor John Bierhost (de) collected and published a Venezuelan version titled "The Horse of Seven Colors".[205]

Argentina

[edit]Folklorist and researcher Berta Elena Vidal de Battini collected a variant from Neuquén Province (Argentina), titled El Caballo de Siete Colores ("The Horse of Seven Colors"): youngest son Manuelito traps a talking horse that has been eating his father's wheat crops, but frees him in exchange for the services of the horse. Manuelito's envious brothers try to kill the boy, but fail, thanks to the horse's protection. Later, Manuelito becomes aware of a princess in a city who will marry the man who can ride at full speed and grab an apple from the princess's hand.[206][b]

Brazil

[edit]Author Elsie Spicer Eells recorded a Brazilian variant titled The Three Horses: the youngest of three brothers tries to seek his own fortune and arrives at a kingdom where the royal gardens were being trampled by wild horses. He manages to tame the horses and gain their trust. In return, the steeds (one of a white color, another of a black color and the third of a sorrel tone) help him win the hand of the princess.[207]

Brazilian folklorist Sergio Romero collected a variant from Sergipe, Chico Ramela: the Virgin Mary, the hero's godmother, disguised as an old lady, instructs the titular Chico Ramela on how to free his elder brothers from the princess. Soon after, the ungrateful brothers take him as their servant and the trio reaches another kingdom. In this new place, the hero discovers and tames three horses.[208]

In another variant, from Minas Gerais, Os Cavalos Mágicos ("The Magical Horses"), by Lindolfo Gomes, the Virgin Mary gives the hero some items to use in his midnight watch for the three enchanted horses.[209]

Asia

[edit]Middle East

[edit]In an Arab tale, "Три призрака" ("Three Ghosts"), a father's dying wish is for his three sons, Omar, Zeid and Muhammed, to guard his grave for three days and three nights. When the time comes, Mohammed fills in for his brothers, and stops three ghostly riders (a white, a black, and a red) to seek revenge on his father. He defeats the ghosts and steal their horses. Next, a padishah announces a racing contest: whoever defeats his daughter, the vizier's daughter and the magistrate's daughter, shall win them for wives. Mohammed uses the horses and wins them as wives for himself and his brothers.[210]

Turkey

[edit]Scholars Wolfram Eberhard and Pertev Naili Boratav established a catalogue for Turkish folktales, the Typen türkischer Volksmärchen ("Turkish Folktale Catalogue"). In their joint work, Eberhard and Boratav grouped tales with the helpful horse under Turkish type TTV 73, "Das wunderbare Pferde" ("The Wonderful Horse"), which corresponded in the international classification to tale type AaTh 530.[211] Eberhard and Boratav listed three Turkish variants: in one, the hero rides the horse up a Crystal Mountain as part of an engagement challenge; in another, the hero has to take off the princess's ring while riding past her.[212]

Researcher Barbara K. Walker published a Turkish tale titled Keloğlan and the Magic Hairs, collected from an informant from Trabzon. In this tale, Keloğlan is a bald-headed boy. His two older brothers order him around. One day, Keloğlan hears the town crier's announcement and goes back home to tell his brothers: the padishah is summoning all horsemen skillful enough to take part in a challenge for the hand of the princess. After his elder brothers go to the padishah's palace, Keloğlan takes out a white hair that an old man gave him and summons a white horse with white garments. Back to the padishah's palace, the princess declares she shall marry one that can jump on a horse over the ravine behind the palace. Keloğlan, in white garments, beats the challenge, but, since he rode back to his home, neither the padishah nor the princess can find him. So the princess issues a second challenge the next day: to jump over an even wider part of the ravine. Keloğlan takes out a tuft of brown hair and summons a brown horse with brown garments, and rides to the second challenge. Thirdly, the princess orders a giant hurdle to be built, and two women to stand behind it with two red stamps to mark the horseman that jumps over it. Keloğlan takes out a black hair and summons a black horse with black garments. He beats the challenge, and is stamped with the red marks, and vanishes back to his house soon after. The princess then asks her father to summon every man to the palace, so that she can identify the mysterious horseman.[213]

Assyrian people

[edit]French orientalist Frédéric Macler collected a Chaldean variant titled Le Testament du Roi ("The King's Will"). In this story, the king asks his sons to ensure that his coffin will not be disturbed after he is interred. His youngest son is the only one to pay heed to the king's request and, during three nights, stops three bandits from desecrating his father's grave and taking revengs on his corpse. The youth kills the bandits and steals their (red, black and white) garments and (red, black and white) horses. Later, he takes part in a horse-racing contest to win three brides for himself and his brothers.[214] The tale was later translated to Russian language by Russo-Assyrian author Konstantin P. (Bar-Mattai) Matveev with the title "Завещание царя" ("The King's Testament"), and published in a compilation of folktales from the Assyrian people.[215]

Iraq

[edit]In an Iraqi folktale, collected by E. S. Drower, The Boy and the Deyus, a dying king has two wishes for his sons and daughters: one, to guard his tomb from any one who tries to profane his grave, and to marry his daughters to the first passersby. The youngest son guards the tomb from three "deyus", one riding a "coal-black" mare in the first night, a second one on a red mare and a third on a white mare. The prince kills the deyus and takes the mares for himself. Meanwhile, the youth also marries his sisters to three passing "darwishes". Later on, the prince learns of a challenge set by a neighbouring Sultan: he ordered a wide and deep ditch to be dug out and their daughters to be put there, until someone rescued them.[216]

Pamir Mountains

[edit]In a tale from the Pamir Mountains, "Царевич и маланг" ("The Prince and the Malang"), a king orders his three sons, two from one wife and the youngest from another, to guard his grave. The first two princes fail, but the youngest protects the grave: a cloud descends from the sky and materializes next to the king's grave. It is a diva, who has promised three horses to the king, but delivers the horses to the prince. Meanwhile, a king with no children is contacted by a malang with an apple as a birthing implement to give to his wife, with the promise to deliver one of his daughters to him. Three daughters are born and, after they grow up, he builds a "козлодранья" (a racing course for a typical Central Asian equestrian game, like the Buzkashi), with enormous walls adorned with battlements. He wraps three kerchiefs around poles, plants them like flags, and announces that he will win his daughters for wife who circles the square three times and removes the kerchiefs. The youngest son summons the horse, beats the challenge and wins a wife. The tale continues as he has to deal with the malang, who comes to collect his due.[217]

Tajikistan

[edit]In a Tajik tale, "Отцовское наставление" ("A Father's Instructions"), a miller shares his property with two of his sons, while the youngest is advised to visit his father's grave for three nights. While working as a shepherd for his brothers, he takes the flock to his father's grave before sunrise for three times, and each time a winged horse appears, the first of a black color, the second of a chestnut horse and the third of a white color - each giving a hair of their mane to the youth. One day, the king announces a contest: to know the best rider in the kingdom, they must climb up a set of 40-step ladders. The youngest brother uses the horses to win the contest.[218]

Turkmenistan

[edit]In a tale from Turkmenistan, "Мамед" ("Mamed"), an old man marries his three daughters to three animals: the oldest to the wolf, the middle one to the tiger, and the youngest to the lion. Some time later, the old man is dying, and asks his three sons to hold a vigil on his grave for three nights. Only the youngest fulfills the request: on each night, a knight riding on a horse appears in a whirlwind near the grave, and gives him a tuft of hair, each from a different horse (the first red, the second a chestnut horse, and the third a gray horse). Then, the king announces that whoever jumps over a plane tree riding a horse, shall marry his daughters. Mamed summons the horses, jumps over the plane tree and throws an apple each time for each of the three princesses. Mamed gives the elder princesses to his brothers and marries the youngest. One day, a div on a horse kidnaps his wife and his animal brothers-in-law help him to rescue her (tale type ATU 552, "The Girls who Married Animals").[219]

Uzbekistan

[edit]In an Uzbek tale titled "Завещание отца" ("The Father's Will"), a father asks his sons to guard his grave when he dies. The youngest promises to do so. When the time comes, the youngest goes to his grave and on each night, at midnight, a horse appears and circles the grave to honor its fallen rider: a white horse on the first, a black horse on the second, and a roan/red horse on the last. Each horse gives him a tuft of hair. Some time later, the three brothers go to the city, where the local ruler build a verandah on top of a high palace wall, with a steep staircase for access. The ruler promises to marry his daughter to anyone who climbs the staircase to reach the princess, be it on horse, on camel or on donkey.[220]

Iran

[edit]Professor Ulrich Marzolph, in his catalogue of Persian folktales, listed three Iranian variants of type 530, Die Grabwache; Prinzessinnen erlangt ("The Grave Watch; Princesses Won"). These tales are about the youngest prince holding a vigil on his father's grave, his killing/defeating three knights that wanted to attack it, and obtaining three magical horses.[221]

In a variant published by professor Mahomed-Nuri Osmanovich Osmanov (ru) with title "Сказка о трех померанцах" ("The tale of the Three Pomerancs"), a dying merchant orders his sons to guard his grave for three nights. Meanwhile, a padishah erects a glass pillar and places three pomerancs atop of it; he declares that whoever gets the big fruit, shall marry his eldest daughter, and so and so forth for the other daughters. The merchant's youngest son digs up a hole next to his father's grave, and awaits through the night until a rider appears on a horse to burn the grave. The son defeats the rider three times and gets hairs from his three horses.[222]

Afghanistan