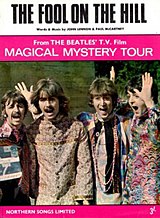

The Fool on the Hill

| "The Fool on the Hill" | |

|---|---|

Northern Songs sheet music cover | |

| Song by the Beatles | |

| from the EP and album Magical Mystery Tour | |

| Released | |

| Recorded | 25–27 September and 20 October 1967 |

| Studio | EMI, London |

| Genre | Psychedelic pop[1] |

| Length | 3:00 |

| Label | Parlophone (UK), Capitol (US) |

| Songwriter(s) | Lennon–McCartney |

| Producer(s) | George Martin |

| Licensed audio | |

| "The Fool on the Hill" (Remastered 2009) on YouTube | |

"The Fool on the Hill" is a song by the English rock band the Beatles from their 1967 EP and album Magical Mystery Tour. It was written and sung by Paul McCartney and credited to the Lennon–McCartney partnership. The lyrics describe the titular "fool", a solitary figure who is not understood by others, but is actually wise. McCartney said the idea for the song was inspired by the Dutch design collective the Fool, who derived their name from the tarot card of the same name, and possibly by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi.

The song's segment in the Magical Mystery Tour television film was shot separately from the rest of the film and without the other Beatles' knowledge. Accompanied by a professional cameraman, McCartney filmed the scene near Nice in France.

In 1968, Sérgio Mendes & Brasil '66 recorded a cover version of the song that reached the top ten in the US. By the late 1970s, "The Fool on the Hill" was one of McCartney's most widely recorded ballads. A solo demo and an outtake of the song were included on the Beatles' 1996 compilation album Anthology 2.

Background and lyrics

[edit]The song's lyrics describe the titular "fool", a solitary figure who is not understood by others, but is actually wise.[2] In his authorised biography, Many Years from Now, Paul McCartney says he first got the idea for the premise from the Dutch design collective the Fool, who were the Beatles' favourite designers in 1967 and told him that they had derived their name from the Tarot card of the same name.[3] According to McCartney, the song possibly relates to a character such as Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the Beatles' meditation teacher:[4]

"Fool on the Hill" was mine and I think I was writing about someone like Maharishi. His detractors called him a fool. Because of his giggle, he wasn't taken too seriously. It was this idea of a fool on the hill, a guru in a cave, I was attracted to ... I was sitting at the piano at my father's house in Liverpool hitting a D 6th chord, and I made up "Fool on the Hill".[5]

Alistair Taylor, in his book Yesterday, reports a mysterious incident involving a man who inexplicably appeared near him and McCartney during a walk on Primrose Hill and then disappeared again, soon after McCartney and Taylor had conversed about the existence of God. In Taylor's account, this incident prompted McCartney to write "The Fool on the Hill".[6]

McCartney played the song for John Lennon during a writing session for "With a Little Help from My Friends" in March 1967.[7] At this point, McCartney had the melody but the lyrics remained incomplete until September.[8] Lennon told him to write it down; McCartney said he did not need to, because he was sure he would not forget it.[9] In his 1980 interview with Playboy magazine, Lennon said, "Now that's Paul. Another good lyric. Shows he's capable of writing complete songs."[10]

Composition

[edit]The song involves alternations of D major and D minor in a similar manner to Cole Porter's alternations of C minor and C major in "Night and Day".[11] The verses are in the major key while the chorus changes to the parallel minor, indicating the confusion implied by the song title.[12] Ian MacDonald says the change to the parallel minor key effectively conveys "the simultaneously literal and metaphorical sense of the sun going behind a cloud".[13]

The D major tonality that begins with an Em7 chord on "Nobody wants to know him" moves through a ii7–V7–I6–vi7–ii7–V7 progression until the shift to the Dm tone and key on "but the fool". According to musicologist Dominic Pedler, other highlights are the use in the Dm section of a minor sixth (B♭) melody note on the word "sun" (with a Dm♯5 chord) and a major ninth (E melody note) on the word "world" (with a Dm chord).[14]

Recording

[edit]The Beatles recorded "The Fool on the Hill" for their Magical Mystery Tour film project.[15] It was the band's first project following the death of their manager, Brian Epstein; according to publicist Tony Barrow, McCartney envisaged the film establishing a "whole new phase of their career" with himself as "the film producer of the Beatles".[16] McCartney first taped a solo demo of the song on 6 September 1967.[17] This version was later released on the Anthology 2 compilation.[8] Recording began in earnest on 25 September, with significant overdubs by the Beatles on 26 September. Mark Lewisohn said that the 26 September version was "almost a re-make".[18] A take from 25 September – noticeably slower, somewhat heavier and with slightly different vocals[19] – is also included on Anthology 2.[20] After another session on 27 September, where McCartney added another vocal,[21] the song sat for a month before flutes were added on 20 October.[22] The recording includes a tape loop of bird-like sounds, heard towards the end of the song, that recalls the seagull effect heard in "Tomorrow Never Knows".[23]

Sequence in Magical Mystery Tour film

[edit]According to Alistair Taylor, McCartney "disappeared" in late October and it was only on his return that the others learned that he had been to France to film a sequence for "The Fool on the Hill".[24] McCartney flew to Nice with cameraman Aubrey Dewar and filmed the sequence at dawn on 31 October. The location was in the mountains inland from the city. McCartney mimed to the song as Dewar filmed the sunrise.[25] The clip was the only musical segment filmed at an exterior location and using professional photography,[26] and the shoot took place when the rest of the Magical Mystery Tour footage was well into the editing stage.[27][28] Peter Brown, who was coordinating the Beatles' business affairs following Epstein's death, recalled that McCartney phoned him from Nice asking for new camera lenses to be sent out for the shoot. According to Brown, the cost for the location filming was considerable, at £4000.[29] In Taylor's description, the footage was "terrific" and "really complemented the song".[24]

The clip shows McCartney in contemplation[30] and cavorting on the hillside.[31] He recalled that he "ad-libbed the whole thing" and that his directions to Dewar were: "Right get over there: Let me dance. Let me dance from this rock to this rock. Get a lot of the sun rising ..."[32] According to author Philip Norman, while the non-musical portions of Magical Mystery Tour were uninspired, the "serial pop video" aspect of the TV film succeeds as a "tour through three rapidly emerging solo talents" in Lennon, McCartney and Harrison. He says the sequence for McCartney's "almost 'Yesterday'-size future standard" shows the singer "on a Provençal mountainside, all big brown eyes and turned-up overcoat".[33] Author Jonathan Gould describes the sequence as "over-lush footage of Paul on a hill ... playing the Fool as if the Fool were a model in a fashion ad".[34]

Release

[edit]"The Fool on the Hill" and the five other songs from the television film were compiled for release on a double EP, except in the United States, where Capitol Records chose to augment the line-up with the Beatles' non-album single tracks from 1967 and create an LP record.[35][36] The Capitol release took place on 27 November 1967, while Parlophone issued the EP on 8 December.[37][38] "The Fool on the Hill" appeared as the opening track on side three in the EP package.[39] On the LP, it was sequenced as the second track on side one,[40] following "Magical Mystery Tour".[41]

The song's segment in the Magical Mystery Tour film proved the most problematic during the editing process since McCartney and Dewar had failed to use a clapperboard.[42] The film was broadcast in the UK on BBC1 on 26 December, but in black and white rather than colour.[43][44] It was the Beatles' first critical failure.[45] As a result of the unfavourable reviews, networks in the US declined to show the film there.[43][46] Brown blamed McCartney for its failure. Brown said that during a private screening for management staff, the reaction had been "unanimous ... it was awful", yet McCartney was convinced that the film would be warmly received, and ignored Brown's advice to scrap the project and save the band from embarrassment.[47] In Many Years from Now, McCartney cites the inclusion of Lennon's "I Am the Walrus" as justification for Magical Mystery Tour and highlights the sequence for "The Fool on the Hill" as another of the film's redeeming features.[48]

In 1973, three years after the Beatles' break-up, "The Fool on the Hill" was included on the band's compilation album 1967–1970.[49] The song plays over the opening titles of the 2010 Jay Roach film Dinner for Schmucks, marking a relatively rare example of a Beatles recording being licensed for use in a feature film. Reports at the time claimed that Paramount/DreamWorks paid $1.5 million for the song, although Paramount later said that the figure was under $1 million.[50] In 2011, a new mix of "The Fool on the Hill" was issued as an iTunes-exclusive bonus track with the download release of the Beatles' 2006 album Love.[51]

Critical reception

[edit]Unlike the film, the Magical Mystery Tour EP and album were well received by critics.[43][52] Bob Dawbarn of Melody Maker described the EP as "six tracks which no other pop group in the world could begin to approach for originality combined with the popular touch".[53] He found "The Fool on the Hill" likeable from the first listen as a "typical Beatle lyrical ballad", and said it would make an "excellent single A-side".[54] In Saturday Review magazine, Mike Jahn highlighted the song as an example of how the album successfully conveyed the Beatles' "acquired Hindu philosophy and its subsequent application to everyday life", in this instance by describing "a detached observer, a yogin, who meditates and watches the world spin".[55] Richard Goldstein of The New York Times rued that, more so than Sgt. Pepper, the soundtrack demonstrated the Beatles' departure from true rock values and an over-reliance on studio artifice and motif, such that when "the hero of 'The Fool On The Hill' sees the world spinning round, we whirl gently amid dizzy rhythms". He nevertheless found the song "so easy to adore", with a melody that he deemed "the most haunting thing on the album", and concluded: "The fool as visionary is a common theme ... But there are lovely ways of presenting cliché, and this is one of them."[56]

Rex Reed, in a highly unfavourable review of the LP for HiFi/Stereo Review, described "The Fool on the Hill" as "the only item on the disc that is not distorted so much that you can't understand the lyrics" and admired the flutes on the recording. Having dismissed the Beatles as "lousy entertainers and downright untalented, tone-deaf musicians", he added that the song "will probably be picked up by people who can sing, and then maybe I will like it even more".[57] Robert Christgau, writing for Esquire in May 1968, said the song "shows signs of becoming a favorite of the Simon & Garfunkel crowd and the transcendental meditators, who deserve it. A callow rendering of the outcast-visionary theme, it may be the worst song the Beatles have ever recorded." Christgau added that McCartney "should know better by now", but also conceded that the new material was meant to be heard in the context of the Magical Mystery Tour TV film.[58] In his article "Rock and Art" for Rolling Stone in July that year, Jon Landau rued that the basic values of rock 'n' roll music had been lost to an artistic aesthetic, a trend he found particularly evident in the Beatles' recent work. He said the song represented the "complete negation of their earlier selves" and contained "all the qualities that the early Beatles sought to deflate: it is pious, subtly self-righteous, humorless and totally unphysical."[59]

NME critics Roy Carr and Tony Tyler described the song as "exquisite" and paired it with "I Am the Walrus" as being "by far the most outstanding cuts" on the Magical Mystery Tour soundtrack.[60] Writing in his book The Beatles Forever, Nicholas Schaffner identified the same tracks as "two of the most impressive Beatle songs ever". He said "The Fool on the Hill" was among McCartney's "most irresistible, universal" ballads, with a lyric that successfully transposed into pop music the literary theme established through fairy tales, through stories of monarchs prizing their court jester over more learned counsel, and in Dostoevsky's popular novel The Idiot.[61]

Bob Woffinden said the film project was undertaken too quickly after Epstein's death, at McCartney's insistence, and McCartney's misguided leadership was also reflected in the "particularly narcissistic" sequence he created for "The Fool on the Hill".[62] Tim Riley writes that unlike the sharp insights offered by fools in Shakespeare's works, the lyrics teach the listener "Little or nothing, except how to pull the heartstrings." Riley concludes: "Possibilities in this song outweigh its substance – it's the most unworthy Beatles standard since 'Michelle.'"[26] Ian MacDonald admires the melody as "poignantly expressive" and says the lyric "skirts sentiment by never committing itself, remaining open to several different interpretations".[63] He describes the song as "an airy creation, poised peacefully above the world in a place where time and haste are suspended" and says that its "timeless appeal ... lies in its paradoxical air of childlike wisdom and unworldliness".[64] Writing for Rough Guides, Chris Ingham includes "The Fool on the Hill" among the Beatles' "essential" songs.[65] He calls the melody "bewitching" and adds: "part of the joy of the piece is the finely judged lyrical ambiguity that, along with the beautiful spaciousness of the arrangement (all flutes, recorders, bass harmonica and whispery brushes on the drums), allows a myriad of implied meanings to float beguilingly into the imagination of the listener."[66]

In 2012, "The Fool on the Hill" was ranked the 420th-best classic rock song of all time by New York's Q104.3.[67] In 2006, Mojo ranked it 71st in the magazine's list of "The 101 Greatest Beatles Songs".[68] In 2018, the music staff of Time Out London ranked it at number 34 on their list of the best Beatles songs.[69]

McCartney live performances

[edit]The Beatles were no longer performing concerts when they released "The Fool on the Hill". McCartney considered including it in the set list for his and Wings' 1975–76 world tour[70] – the first time he conceded to playing Beatles songs with Wings – but decided against it.[71] Wings performed it throughout their 1979 tour of the UK.[72][73]

McCartney included "The Fool on the Hill" on his 1989–1990 world tour.[74] Keen to embrace his Beatles past, he played it on the same multi-coloured piano he had used for writing during the 1960s; he introduced the instrument as the "Magic Piano".[75] His performances of the song incorporated sound bites from Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech.[76] In his press conference on the final day of the world tour, McCartney commented that the song was about "someone who's got the right answer but people tend to ridicule him".[77] A live version from McCartney's concert at London's Wembley Arena on 13 January 1990[78] was included on the album Tripping the Live Fantastic.[79] The song surfaced again for McCartney's 2001–2002 tours, and another live version appeared on the Back in the U.S. album.[80]

Cover versions

[edit]Sérgio Mendes & Brasil '66

[edit]| "The Fool on the Hill" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single by Sérgio Mendes & Brasil '66 | ||||

| from the album Fool on the Hill | ||||

| B-side | "So Many Stars" | |||

| Released | July 1968 | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 3:15 | |||

| Label | A&M | |||

| Songwriter(s) | Lennon–McCartney | |||

| Producer(s) | Sérgio Mendes, Herb Alpert, Jerry Moss[84] | |||

| Sérgio Mendes & Brasil '66 singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Official audio | ||||

| "The Fool on the Hill" on YouTube | ||||

Sérgio Mendes & Brasil '66 recorded "Fool on the Hill", using their approach of marrying a simple bossa nova rhythm with a string accompaniment.[85] The co-lead vocals were by Lani Hall and Karen Philipp. Released as a single in late July 1968,[84] the song reached number 6 on the US Billboard Hot 100[85] and topped Billboard's Easy Listening chart for six weeks.[86] It was also the title track of Mendes' 1968 album Fool on the Hill.[85]

In 2018, Mendes recalled that he was introduced to the Beatles' Magical Mystery Tour album over Christmas 1967 by Herb Alpert, his producer. Impressed with the melody of "The Fool on the Hill", he thought, "Wow, I think I can do a totally different arrangement." He said McCartney later wrote him a letter to thank him for his version of the song.[81]

Other artists

[edit]By the late 1970s, "The Fool on the Hill" was one of McCartney's most widely recorded ballads.[87] According to Ingham, it was especially popular among cabaret performers during the late 1960s.[65] In 1971, a recording by Shirley Bassey peaked at number 48 on the UK singles chart.[88] Helen Reddy recorded the song for All This and World War II,[89] a 1976 film in which wartime newsreel was set to a soundtrack of Lennon–McCartney songs.[90] According to author Robert Rodriguez, it was one of the few "clever juxtapositions" in the film,[91] as the song plays over footage of Adolf Hitler at his mountain hideaway in Berchtesgaden.[92] The duo Eurythmics, nine years after disbanding, reunited in January 2014 to perform "The Fool on the Hill" for The Night That Changed America: A Grammy Salute to the Beatles.[93][94]

This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: other cover artists may not meet WP:SONGCOVER. (March 2020) |

The following are among the many other artists who have covered the song: the Four Tops, Björk, Sarah Vaughan, Aretha Franklin, Petula Clark, John Williams, Santo & Johnny, Ray Stevens, Bobbie Gentry, Eddie Fisher, Lena Horne with Gábor Szabó, Micky Dolenz, Stone the Crows, Vera Lynn, Enoch Light, Andre Kostelanetz, the Boston Pops Orchestra, Corry Brokken, the King's Singers, Zé Ramalho, Bud Shank, Mulgrew Miller, the Chopsticks, Mark Mallman, Lana Cantrell, Barry Goldberg, Sharon Tandy, Libby Titus, the Singers Unlimited, Isabelle Aubret and Eddy Mitchell.[30]

Personnel

[edit]According to Ian MacDonald (except where noted), the following musicians played on the Beatles' recording:[7]

The Beatles

- Paul McCartney – vocals, piano, acoustic guitar, recorder, bass, penny whistle[95]

- John Lennon – classical guitar, bass harmonica, Jew's harp

- George Harrison – 12-string acoustic guitar,[96] bass harmonica

- Ringo Starr – drums, maracas, finger cymbals

Additional musicians

- Christopher Taylor, Richard Taylor, Jack Ellory – flutes

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Rolling Stone Staff (24 September 2024). "The 101 Greatest Soundtracks of All Time". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 5 October 2024.

...featuring studio-tweaked psych-pop bedrock like "I Am the Walrus", "The Fool on the Hill", and the title track...

- ^ Gould 2007, p. 455.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 343.

- ^ Ingham 2006, p. 201.

- ^ Miles 1997, pp. 365–66.

- ^ Womack 2014, p. 280.

- ^ a b MacDonald 1998, p. 237.

- ^ a b Winn 2009, p. 121.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 366.

- ^ Sheff 2000, p. 186.

- ^ Pedler 2003, pp. 183–84.

- ^ Riley 2002, p. 239.

- ^ MacDonald 1998, p. 339.

- ^ Pedler 2003, p. 184.

- ^ Sounes 2010, p. 178.

- ^ Greene 2016, p. 38.

- ^ Lewisohn 2005, p. 123.

- ^ Lewisohn 2005, p. 126.

- ^ Anthology 2 (booklet). The Beatles. Apple Records. 1996. pp. 41–42. 31796.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Winn 2009, pp. 125–26.

- ^ Lewisohn 2005, p. 127.

- ^ Winn 2009, p. 132.

- ^ Womack 2014, p. 281.

- ^ a b Barrow, Tony (1999). The Making of The Beatles' Magical Mystery Tour. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 0-7119-7575-2. No page numbers appear.

- ^ Miles 2001, p. 282.

- ^ a b Riley 2002, p. 240.

- ^ Ingham 2006, p. 161.

- ^ Sounes 2010, p. 198.

- ^ Brown & Gaines 2002, p. 254.

- ^ a b Fontenot, Robert. "The Beatles Songs: 'The Fool on the Hill' – The history of this classic Beatles song". About.com Entertainment. oldies.about.com. Archived from the original on 4 April 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 131.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 365.

- ^ Norman 2008, p. 528.

- ^ Gould 2007, p. 456.

- ^ Lewisohn 2005, p. 131.

- ^ Greene 2016, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Miles 2001, pp. 284, 285.

- ^ Winn 2009, p. 80.

- ^ Miles 2001, p. 285.

- ^ Turner 2012, p. 251.

- ^ Ingham 2006, p. 47.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 364.

- ^ a b c Everett 1999, p. 132.

- ^ Greene 2016, pp. 38–39.

- ^ MacDonald 1998, p. 224.

- ^ Greene 2016, p. 39.

- ^ Brown & Gaines 2002, pp. 254–55.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 372.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, pp. 158, 207.

- ^ Goldstein, Patrick; Rainey, James (22 July 2010). "The Big Picture: How did Jay Roach get a Beatles song for 'Dinner for Schmucks'?". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ EMI Music/Apple Corps Ltd/Cirque du Soleil (1 February 2011). "The Beatles' Grammy-Winning 'LOVE' Album and 'All Together Now' Documentary Film to Make Digital Debuts Exclusively on iTunes Worldwide" (Press release). PR Newswire. Archived from the original on 1 August 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, p. 90.

- ^ Shaar Murray, Charles (2002). "Magical Mystery Tour: All Aboard the Magic Bus". Mojo Special Limited Edition: 1000 Days That Shook the World (The Psychedelic Beatles – April 1, 1965 to December 26, 1967). London: Emap. p. 128.

- ^ Dawbarn, Bob (25 November 1967). "Magical Beatles – in Stereo". Melody Maker. p. 17.

- ^ Jahn, Mike (December 1967). "The Beatles: Magical Mystery Tour". Saturday Review. Available at Rock's Backpages Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine (subscription required).

- ^ Goldstein, Richard (31 December 1967). "Are the Beatles Waning?". The New York Times. p. 62.

- ^ Reed, Rex (March 1968). "Entertainment (The Beatles Magical Mystery Tour)" (PDF). HiFi/Stereo Review. p. 117. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (May 1968). "Columns: Dylan-Beatles-Stones-Donovan-Who, Dionne Warwick and Dusty Springfield, John Fred, California (May 1968, Esquire)". robertchristgau.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2015. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- ^ Gendron 2002, pp. 210, 346.

- ^ Carr & Tyler 1978, p. 70.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, pp. 90, 91.

- ^ Woffinden 1981, pp. 1, 3.

- ^ MacDonald 1998, pp. 237, 238.

- ^ MacDonald 1998, p. 238.

- ^ a b Ingham 2006, p. 48.

- ^ Ingham 2006, pp. 200–01.

- ^ "The Top 1,043 Classic Rock Songs of All Time: Dirty Dozenth Edition". Q1043.com. Archived from the original on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ^ Alexander, Phil; et al. (July 2006). "The 101 Greatest Beatles Songs". Mojo. p. 68.

- ^ Time Out London Music (24 May 2018). "The 50 Best Beatles songs". Time Out London. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ Riley 2002, pp. 359–60.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, p. 182.

- ^ Madinger & Easter 2000, p. 254.

- ^ Badman 2001, p. 238.

- ^ Madinger & Easter 2000, p. 317.

- ^ Sounes 2010, p. 421.

- ^ Pereles, Jon (13 December 1989). "More Nostalgia Than Rock in Paul McCartney's Return". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 February 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2011.

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 340.

- ^ Badman 2001, p. 439.

- ^ Madinger & Easter 2000, p. 334.

- ^ Ingham 2006, p. 122.

- ^ a b Shand, John (26 March 2018). "Sergio Mendes story: Making songs by the Beatles and Bacharach shine anew". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 27 July 2019. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ Stanley, Bob (13 September 2013). "Pop Gets Sophisticated: Soft Rock". Yeah Yeah Yeah: The Story of Modern Pop. Faber & Faber. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-571-28198-5.

- ^ Margolis, Lynne (1 January 1998). "Sergio Mendes". In Knopper, Steve (ed.). MusicHound Lounge: The Essential Album Guide. Detroit: Visible Ink Press. pp. 328–329.

- ^ a b Billboard Review Panel (3 August 1968). "Spotlight Singles". Billboard. p. 74.

- ^ a b c Ginell, Richard S. "Sergio Mendes/Sergio Mendes & Brasil '66 Fool on the Hill". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 22 June 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ^ Whitburn 1996.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, p. 91.

- ^ "Shirley Bassey". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ Film Threat admin (1 October 2004). "The Bootleg Files: 'All This and World War II'". Film Threat. Archived from the original on 27 July 2019. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, pp. 171–72.

- ^ Rodriguez 2010, p. 91.

- ^ Badman 2001, p. 196.

- ^ Appleford, Steve (28 January 2014). "McCartney and Starr Team Again as Eurythmics, Grohl Honor the Beatles". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 26 July 2019. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ Kaye, Ben (11 February 2014). "Watch: The Beatles tribute concert featuring Paul McCartney, Dave Grohl, Eurythmics, and more". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on 26 July 2019. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ George Martin interviewed on the Pop Chronicles (1969)

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 138.

Sources

[edit]- Badman, Keith (2001). The Beatles Diary Volume 2: After the Break-Up 1970–2001. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-8307-6.

- Brown, Peter; Gaines, Steven (2002) [1983]. The Love You Make: An Insider's Story of the Beatles. New York, NY: New American Library. ISBN 978-0-4512-0735-7.

- Carr, Roy; Tyler, Tony (1978). The Beatles: An Illustrated Record. London: Trewin Copplestone. ISBN 0-450-04170-0.

- Everett, Walter (1999). The Beatles as Musicians: Revolver through the Anthology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512941-0.

- Gendron, Bernard (2002). Between Montmartre and the Mudd Club: Popular Music and the Avant-Garde. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-28737-9.

- Gould, Jonathan (2007). Can't Buy Me Love: The Beatles, Britain, and America. New York, NY: Harmony Books. ISBN 978-0-307-35337-5.

- Greene, Doyle (2016). Rock, Counterculture and the Avant-Garde, 1966–1970: How the Beatles, Frank Zappa and the Velvet Underground Defined an Era. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-6214-5.

- Ingham, Chris (2006). The Rough Guide to the Beatles. London: Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-84353-720-5.

- Lewisohn, Mark (2005) [1988]. The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions: The Official Story of the Abbey Road Years 1962–1970. London: Bounty Books. ISBN 978-0-7537-2545-0.

- MacDonald, Ian (1998). Revolution in the Head: The Beatles' Records and the Sixties. London: Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-6697-8.

- Madinger, Chip; Easter, Mark (2000). Eight Arms to Hold You: The Solo Beatles Compendium. Chesterfield, MO: 44.1 Productions. ISBN 0-615-11724-4.

- Miles, Barry (1997). Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 0-8050-5249-6.

- Miles, Barry (2001). The Beatles Diary Volume 1: The Beatles Years. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 0-7119-8308-9.

- Norman, Philip (2008). John Lennon: The Life. New York, NY: Ecco. ISBN 978-0-06-075402-0.

- Pedler, Dominic (2003). The Songwriting Secrets of the Beatles. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-8167-6.

- Riley, Tim (2002) [1988]. Tell Me Why – The Beatles: Album by Album, Song by Song, the Sixties and After. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81120-3.

- Rodriguez, Robert (2010). Fab Four FAQ 2.0: The Beatles' Solo Years, 1970–1980. Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-1-4165-9093-4.

- Schaffner, Nicholas (1978). The Beatles Forever. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-055087-5.

- Sheff, David (2000) [1981]. All We Are Saying: The Last Major Interview with John Lennon and Yoko Ono. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-25464-4.

- Sounes, Howard (2010). Fab: An Intimate Life of Paul McCartney. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-723705-0.

- Turner, Steve (2012) [1994]. A Hard Day's Write: The Stories Behind Every Beatles Song. London: Carlton Books. ISBN 978-1-78097-096-7.

- Whitburn, Joel (1996). The Billboard Book of Top 40 Hits (6th ed.). New York: Billboard Publications.

- Winn, John C. (2009). That Magic Feeling: The Beatles' Recorded Legacy, Volume Two, 1966–1970. New York, NY: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-307-45239-9.

- Woffinden, Bob (1981). The Beatles Apart. London: Proteus. ISBN 0-906071-89-5.

- Womack, Kenneth (2014). The Beatles Encyclopedia: Everything Fab Four. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-39171-2.

External links

[edit]- Alan W. Pollack's Notes on "The Fool on the Hill"

- Handwritten lyrics of The Fool on the Hill in The Beatles Loan at the British Library

- The Fool on the Hill on YouTube