Texella cokendolpheri

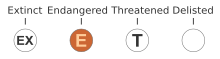

The Cokendolpher cave harvestman, Texella cokendolpheri, is a species of cave-living harvestman (daddy longlegs) native to Bexar County, Texas. The original common name, the Robber Baron Cave harvestman, stemmed from the cave which the harvestman inhabits. The scientific name and the current common name honor the prominent arachnologist, James Cokendolpher, who identified the species.[1] T. cokendolpheri is one of twenty-eight species within the North American harvestman genus Texella. The first formal description of the harvestman took place in 1992[1] and the species’ listing under the Endangered Species Act followed eight years later.[2] Current threats to the species include habitat loss and interactions with invasive fire ants.[3]

| Texella cokendolpheri | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Chelicerata |

| Class: | Arachnida |

| Order: | Opiliones |

| Family: | Phalangodidae |

| Genus: | Texella |

| Species: | T. cokendolpheri

|

| Binomial name | |

| Texella cokendolpheri Ubick and Briggs, 1992

| |

Description

[edit]The adult Cokendolpher cave harvestman is pale orange and roughly textured. They have no eyes. However, they do have round bumps on their heads, called eye mounds, which are vestigial structures where their ancestors previously had eyes. The species’ body is oval shaped and ranges from 1.28 millimeters (mm) (0.05 inches) to 1.67 mm (0.07 inches) in diameter. The length of each of their eight legs ranges from 13.1 mm (0.52 inches) to 13.6 mm (0.54 inches) each. The species is a troglobite, meaning that it is adapted to the darkness of a cave environment. The Cokendolpher cave harvestman’s primary adaptations to its cave habitat are bright orange coloration and the loss of eyes.[1]

Other harvestmen of the Texella genus are dioecious. Males and females exhibit sexual dimorphism. For example, Texella males have more mounds on their hard shell, called a scutum, than females.[5]

Species within the harvestman family Phalangodidae, including T. cokendolpheri, are united by the position of spines on their pedipalps. However, distinguishing this species from closely related harvestmen, such as Texella tuberculata, can only be done by differences in adult male genitals.[1] Such small differences between species make identification of this harvestman challenging.

Life History

[edit]The life cycle of T. cokendolpheri and other species in the Texella genus is not well studied. However, T. cokendolpheri likely shares some characteristics with related, better studied harvestmen. Fertilization of harvestman eggs is internal. After mating, females lay eggs on the ground or inside cracks between rocks.[5] Harvestmen molt between 4 and 7 times during development but do not molt as adults.[5] The life span of harvestmen ranges from several months to several years,[5] but the life span of T. cokendolpheri is unknown.

Ecology

[edit]Diet

[edit]Information about the diet of the T. cokendolpheri is scarce. Other harvestmen species are primarily carnivorous. Many karst invertebrates rely on cave crickets such as Ceuthophilus spp, but it is unclear whether the Cokendolpher cave harvestman eats these insects.[3]

Behavior

[edit]Since identification of the Cokendolpher cave harvestman is difficult, information on the behavior of this species is scarce. While some cave harvestmen are nocturnal,[5] it is not known whether T. cokendolpheri follows this behavioral trend.

Habitat

[edit]The Cokendolpher cave harvestman is an obligate cave dwelling species; they require subterranean habitats with high humidity and stable temperatures.[6] Karst cave habitats in Texas fulfill these conditions and are suitable environments for the Cokendolpher cave harvestman. This species lives in the space between rocks in karst caves.

Range

[edit]T. cokendolpheri inhabits only the mile long Robber Baron cave located in Bexar County, Texas.[7] The 2011 Federal Register indicates that the area is privately owned but highly urbanized.[3] The Cokendolpher cave harvestman has also had one suspected sighting at the John Wagner Ranch #3. However, this individual was a juvenile, so researchers were unable to confirm the species.[1]

Conservation

[edit]Population Size

[edit]Researchers do not have an exact population number for T. cokendolpheri. There have been only three confirmed sightings of individuals of this species. All three specimens were located in the Robber Baron cave.[6] The US Fish and Wildlife Service has suggested that population surveys be conducted to assess the species’ population status.[8]

Past and Current Geographical Distribution

[edit]The Cokendolpher cave harvestman inhabits one cave: the Robber Baron cave in Bexar County, Texas.[6] The range has not changed since the discovery of T. cokendolpheri. However, there has been a lack of research on the distribution.[1]

Major Threats

[edit]The major threat to the Cokendolpher cave harvestman is habitat destruction. The Robber Baron cave where the species lives is highly urbanized, privately owned land.[9] In the past, the cave was a trash dump and a tourist attraction.[9][7] These uses of the cave can harm the Cokendolpher cave harvestman. Many karst organisms are also under threat from groundwater contamination and changes in water flow to karst caves.[3] Additionally, the invasive fire ant species Solenopsis invicta negatively impacts karst environments.[8][10] These ants compete with cave crickets, the primary source of food for many karst animals.[3] Climate change may also impact the species by causing changes in temperature and humidity inside the species’ karst habitats.[8] Cave harvestmen are not resistant to fluctuating environmental conditions.[5]

History of ESA Listing

[edit]A petition to place T. cokendolpheri on the Endangered Species Act was published on January 16, 1992.[2] At that time, the formal description of the species had not yet been released. T. cokendolpheri was officially listed under the Endangered Species Act on December 26, 2000, with a recovery priority of 2C, along with eight other Bexar County karst invertebrates.[6]

5-Year Reviews

[edit]2011

[edit]The first five year review suggested that the priority of the Cokendolpher cave harvestman be upgraded from its initial listing at 2C to 5C. While both priority listings have the same threat level, they differ in their ability to recover after disturbance. 2C species have a high threat level and a high recovery potential. 5C species are unlikely to recover from human disturbance due to extreme endemism. This species is highly endemic and falls under this category. Due to the suggestion of this review, T. cokendolpheri was changed to a recovery priority of 5C because of its limited range.[11]

2020

[edit]The second five-year review does not contribute any new information on the biology of the Cokendolpher cave harvestman. The priority listing for the species remains at 5C. The review suggests biota surveys as a strategy for gaining more information on the Cokendolpher cave harvestman. More data on the species will better inform future recovery plans. Additionally, the review designates habitat critical for the survival of seven of nine karst species in Bexar County. These other karst species include the Canyon Bat Cave spider and the Government Canyon Bat Cave meshweaver. Few protection and conservation strategies changed for T. cokendolpheri in this review.[8]

Recovery Plan

[edit]The US Fish and Wildlife Service published the recovery plan for the Cokendolpher cave harvestman in 2011,[3] the same year the first five year review was released.[11] T. cokendolpheri is currently designated with a recovery priority of 5C. This means that it is unlikely that they will recover in the future. This is due to the species’ small population size and the location of its habitat in a highly urbanized area. The major recovery strategy for T. cokendolpheri is to protect the environment where they live. This strategy will ensure that T. cokendolpheri populations can survive through urban development. Research to understand the biology and ecology of this animal will better inform conservation measures.

The necessary actions outlined by the recovery plan are:

- Habitat protection and management

- Creating a minimum of six protected reserves

- Controlling the spread of invasive fire ants

- Limiting human tourism of caves

- Preventing pollution of caves

- Monitoring and research on the species

- Studying the distribution and distinct populations of T. cokendolpheri

- Creating additional management plans based on research

- Education and outreach programs

- Providing information to the public on karst species, specifically endangered ones such as T. cokendolpheri

- Informing and helping landowners who own land that T. cokendolpher inhabits

- Monitoring plan post-delisting

- Defining gauges of the status of T. cokendolpheri

- Forming protocols for monitoring those gauges

- Consistently evaluating the species for relisting under the ESA[3]

According to the plan, the downlisting of the Cokendolpher cave harvestman could occur within 10 years if all recovery strategies are implemented. In addition, the delisting of the species could occur within 20 years with the appropriate actions.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Ubick, Darrell; Briggs, Thomas (December 1992). "The Harvestman Family Phalangodidae. 3. Revision of Texella Goodnight and Goodnight (Opiliones: Laniatores)" (PDF). Studies on the Cave and Endogean Fauna of North America II. Texas Memorial Museum: 155.

- ^ a b Petition to M. Spear, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Jan 9 1991,https://ecos.fws.gov/docs/tess/petition/219.pdf

- ^ a b c d e f g h U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, "Bexar County Karst Invertebrates Recovery Plan", August 2011, https://ecos.fws.gov/docs/recovery_plan/Final%202001%20Bexar%20Co%20Invertebrates%20Rec%20Plan_1.pdf

- ^ "Texella cokendolpheri". NatureServe Explorer An online encyclopedia of life. 7.1. NatureServe. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Pinto-da-Rocha, Ricardo (2007). Harvestman: The Biology of Opiliones. Harvard University Press.

- ^ a b c d Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Federal Register, Vol 65, No. 248, Dec 26 2000, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2000-12-26/pdf/00-32809.pdf#page=1

- ^ a b Mitchell, Joe. "Robber Baron Cave Preserve". TCMA. Retrieved 2022-04-26.

- ^ a b c d U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Cokendolpher Cave Harvestman (Texella cokendolpheri) 5-Year Review Summary and Evaluation https://ecos.fws.gov/docs/tess/species_nonpublish/3025.pdf

- ^ a b Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Federal Register, Vol. 77, No. 30, Feb 14 2012, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2012-02-14/pdf/2012-2195.pdf#page=2

- ^ Reddell, James; Cokendolpher, James (January 2001). "Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) From the Caves of Belize, Mexico, and California and Texas (U.S.A)" (PDF). Studies on the Cave and Endogean Fauna of North America III. Texas Memorial Museum.

- ^ a b U.S Fish and Wildlife Service, 5-Year Review, Austin TX, https://ecos.fws.gov/docs/tess/species_nonpublish/1789.pdf