Stinnes–Legien Agreement

| Part of a series on |

| Organized labour |

|---|

|

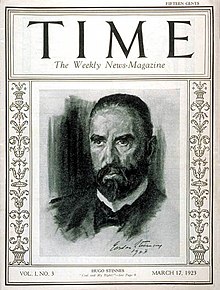

The Stinnes–Legien Agreement (German: Stinnes-Legien-Abkommen) was an accord concluded by German trade unions and industrialists on 15 November 1918.[1] Named after both parties' negotiators in chief, the heavy industry magnate Hugo Stinnes and the union leader Carl Legien, the agreement enshrined a set of workers' rights long coveted by the German labour movement.

Among the stipulations of the treaty were the introduction of the eight-hour working day, the recognition of the trade unions as the official representation of the workforce, and the permission to form workers' councils in firms with more than 50 employees. Since negotiations had been caused by the prospect of millions of soldiers returning from the First World War, the agreement contained a clause guaranteeing them a right to their former employment. While the trade unions were able to realise many of their long-standing demands, they all but acknowledged the private ownership of the means of production.

Background

[edit]Towards the end of the First World War, Germany's trade unions and industrial employers were faced with the prospect of millions of demobilised soldiers returning to the domestic labour market.[2] In the wake of the overthrow of the imperial administrations, the social-democratic provisional government under Chancellor Friedrich Ebert looked to co-operate with the elites in order to prevent an escalation of far-left revolutionary efforts.[3] In a development common across post-war Europe, German industrialists were prepared to make limited concessions to organised labour.[4]

In October 1918, representatives of key industries and the respective unions had met to decide upon joint action to manage the imminent challenge. It was decided that bipartisan committees should develop proposals for the future relationship between the two sides.[2] In early November, summit talks failed to yield a breakthrough because employers would not agree to shorter working hours and the abolition of anti-socialist clubs in their factories.[2]

Agreement

[edit]

On 15 November 1918, a settlement was reached. Named after both parties' negotiators in chief, the heavy industry magnate Hugo Stinnes and the union leader Carl Legien,[2] the pact was named the Stinnes–Legien Agreement (Stinnes-Legien Abkommen).[5] It stipulated that employers acknowledge trade unions as the official representatives of the workforce and recognise their right to collective bargaining. The agreement also introduced the eight-hour day, allowed for the creation of workers' councils in firms with more 50 employees, and issued a guarantee that returning soldiers would have a right to their pre-war job.[5] Future disputes were to be resolved through a newly created organisation named the "Central Working Group" (Zentralarbeitsgemeinschaft, or ZAG).[6]

Impact

[edit]For the trade unions, the agreement meant the realisation of many of their long-standing goals.[7] However, the implementation of the eight-hour day, one of the central achievements of the agreement, remained inconsistent and was challenged several times during the following decade.[8] The industrialists, on the other hand, had ended organised labour's demands for the socialisation of their factories:[7] by signing the Stinnes–Legien Agreement, the unions had all but acknowledge private ownership of the means of production.[5] The newly created ZAG collapsed in 1924 over a dispute about working hours.[5]

References

[edit]- ^ "Das Novemberabkommen". www.gewerkschaftsgeschichte.de (in German). Retrieved 2023-06-09.

- ^ a b c d Winkler 1993, p. 45.

- ^ Winkler 1993, pp. 44–45.

- ^ "Organized labour – From World War I to 1968: The institutionalization of unions and collective bargaining". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2002.

- ^ a b c d "Das Stinnes-Legien-Abkommen". Deutsches Historisches Museum. Retrieved 2021-03-29.

- ^ Winkler 1993, pp. 45–46.

- ^ a b Winkler 1993, p. 46.

- ^ "Der Kampf um den Achtstundentag". Deutsches Historisches Museum. Retrieved 2021-03-29.

Bibliography

[edit]- Winkler, Heinrich August (1993). Weimar: Die Geschichte der ersten deutschen Demokratie (in German). Munich: C.H. Beck. ISBN 978-3406726927.