Steamboat Willie

| Steamboat Willie | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster[1] | |

| Directed by | |

| Story by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | Walt Disney |

| Music by |

|

| Animation by |

|

| Color process | Black and white |

Production company | |

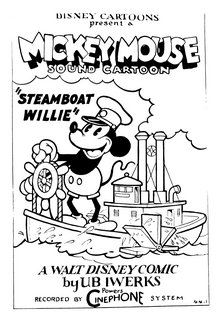

| Distributed by | Pat Powers (Celebrity Productions/Cinephone sound) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 7:47 |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $4,986.69 |

Steamboat Willie is a 1928 American animated short film directed by Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks.[2] It was produced in black and white by Walt Disney Animation Studios and was released by Pat Powers, under the name of Celebrity Productions.[3] The cartoon is considered the public debut of Mickey Mouse and Minnie Mouse, although both appeared months earlier in a test screening of Plane Crazy[4] and the then yet unreleased The Gallopin' Gaucho.[5] Steamboat Willie was the third of Mickey's films to be produced, but it was the first to be distributed, because Disney, having seen The Jazz Singer, had committed himself to produce one of the first fully synchronized sound cartoons.[6]

Steamboat Willie is especially notable for being one of the first cartoons with synchronized sound, as well as one of the first cartoons to feature a fully post-produced soundtrack, which distinguished it from earlier sound cartoons, such as Inkwell Studios' Song Car-Tunes (1924–1926), My Old Kentucky Home (1926) and Van Beuren Studios' Dinner Time (1928). Disney believed that synchronized sound was the future of film. Steamboat Willie became the most popular cartoon of its day.

Music for Steamboat Willie was arranged by Wilfred Jackson and Bert Lewis, and it included the songs "Steamboat Bill", a composition popularized by baritone Arthur Collins during the 1910s, and the popular 19th-century folk song "Turkey in the Straw".[7] The title of the film may be a parody of the Buster Keaton film Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1928),[8] itself a reference to the song by Collins. Disney performed all of the voices in the film, although there is little intelligible dialogue.[a]

The film has received wide critical acclaim, not only for introducing one of the world's most popular cartoon characters but also for its technical innovation. The short is often considered to be one of the most influential cartoons ever made. Animators voted Steamboat Willie as the 13th-greatest cartoon of all time in the 1994 book The 50 Greatest Cartoons, and in 1998, the film was selected by the United States Library of Congress for preservation in the National Film Registry.[10] The cartoon entered the public domain in the United States on January 1, 2024, alongside other works published in 1928.

Background

[edit]Mickey Mouse was created as a replacement for Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, an earlier cartoon character that was originated by the Disney studio but owned at the time by Universal Pictures.[11] The first two Mickey Mouse films produced, silent versions of Plane Crazy and The Gallopin' Gaucho, had failed to gain a distributor. According to Roy O. Disney, Walt Disney was inspired to create a sound cartoon after watching The Jazz Singer (1927). Disney believed that adding sound to a cartoon would greatly increase its appeal.[12] The character of Pete predates Steamboat Willie by multiple years, having appeared as the villain to both Oswald and Disney's first ever cartoon hero, Julius the Cat (an unlicensed derivative character of Felix the Cat) starting with Alice Solves the Puzzle (1925), though he was originally depicted as a bear.

Despite being recognized for it, Steamboat Willie was not the first cartoon with synchronized sound.[13] Starting in May 1924 and continuing through September 1926, Dave and Max Fleischer's Inkwell Studios produced 19 sound cartoons, part of the Song Car-Tunes series, using the Phonofilm sound-on-film process. However, the Song Car-Tunes failed to keep the sound fully synchronized, while Steamboat Willie was produced using a click track to keep his musicians on the beat.[14] As little as one month before Steamboat Willie was released, Paul Terry released Dinner Time, which also used a soundtrack, but Dinner Time was not a financial success.

In June 1927, producer Pat Powers made an unsuccessful takeover bid for Lee de Forest's Phonofilm Corporation. In the aftermath, Powers hired a former DeForest technician, William Garrity, to produce a cloned version of the Phonofilm system, which Powers dubbed "Powers Cinephone". By then, de Forest was in too weak a financial position to mount a legal challenge against Powers for patent infringement. Powers convinced Disney to use Cinephone for Steamboat Willie; their business relationship lasted until 1930 when Powers and Disney had a falling-out over money, and Powers hired away Disney's lead animator, Ub Iwerks.[citation needed]

Plot

[edit]Mickey Mouse is piloting a side-wheeler paddle steamer, cheerfully whistling "Steamboat Bill" and sounding the boat's three whistles. Soon, the captain, Pete, appears and orders Mickey off of the bridge. Annoyed, Mickey blows a raspberry at Pete who afterwards attempts to kick him, but Mickey rushes away in time and Pete accidentally kicks himself in the rear. Mickey falls down the stairs, slips on a bar of soap on the boat's deck, and lands in a bucket of water. A parrot laughs at him and Mickey throws the bucket on its head.

Pete, who has been watching the occurrence, pilots the steamboat himself. He bites off some chewing tobacco and spits into the wind. The spit flies backward and rings the boat's bell. Amused, Pete spits again, but this time the spit hits him in the face, to his dismay.

The steamboat makes a stop at "Podunk Landing" to pick up a cargo of various livestock. Mickey has trouble getting one of the slimmer cows with a FOB tag onto the boat attached to a harness. To solve this, Mickey fills the cow's stomach up with hay to fatten the slim cow into the harness. Just as they set off again, Minnie Mouse appears, running to catch the boat before it leaves. Mickey does not see her in time, but she runs after the boat along the shore calling out Mickey's name. Mickey hears Minnie's calls and he takes her on board by hooking the cargo crane to her bloomers.

Landing on deck, Minnie accidentally drops a ukulele and sheet music for the song "Turkey in the Straw", which are eaten by a goat. After a brief tug of war with the goat over the partially eaten ukulele, Mickey loses his grip and it lands inside the goat. The force from the ukulele makes the goat begin to play musical notes. Mickey, interested, orders Minnie to begin using the goat's body as a phonograph by turning its tail like a crank. Music begins to play which delights the two mice. Mickey uses various objects on the boat as percussion accompaniment, and later on begins to "play" the animals like musical instruments via pulling the tail of a cat, stretching a goose's throat, tugging on the tails of a nursing sow's piglets and using said sow as an accordion, and using a cow's teeth and tongue to play the song as a xylophone.[15][16][17]

Captain Pete is unamused by the musical act and puts Mickey to work peeling potatoes as a punishment. Out of spite, Mickey uses a knife to peel the potatoes wastefully, discarding most of the potato along with the skin. In the potato bin, the same parrot that laughed at him earlier appears in the porthole and laughs at him again. Fed up with the bird's heckling, Mickey throws a half-peeled potato at it, knocking it back into the river below. Mickey then laughs as he sits next to the potatoes and hears the parrot squawking.

Dialogue

[edit]Mickey, Minnie, and Pete perform in near-pantomime, with growls and squeaks but no intelligible dialogue. The only true dialogue in the film is spoken by the ship's parrot. When Mickey falls into a bucket of soapy water, the bird says, "Hope you don't feel hurt, big boy! Ha ha ha ha ha!".[18] After Mickey throws the bucket onto the parrot's head, it cries "Help! Help! Man overboard!". It repeats the phase at the end of the short, after Mickey throws a potato onto the parrot and it falls into the water.[19]

Production

[edit]

The production of Steamboat Willie took place between July and September 1928, which according to Roy O. Disney's personal notes had a budget of $4,986.69 (equivalent to $88,485 in 2023), including the prints for movie theaters.[20] There was initially some doubt among the animators that a sound cartoon would appear believable enough, so before a soundtrack was produced, Disney arranged for a screening of the film to a test audience with live sound to accompany it.[21] This screening took place on July 29, with Steamboat Willie only partly finished. The audience sat in a room adjoining Walt Disney's office. His brother Roy placed the movie projector outdoors and the film was projected through a window so that the sound of the projector would not interfere with the live sound. Ub Iwerks set up a bedsheet behind the movie screen behind which he placed a microphone connected to speakers where the audience would sit. The live sound was produced from behind the bedsheet. Wilfred Jackson played the music on a mouth organ, Ub Iwerks banged on pots and pans for the percussion segment, and Johnny Cannon provided sound effects with various devices, including slide whistles and spittoons for bells. Walt Disney provided what little dialogue there was to the film, mostly grunts, laughs, and squawks. After several practices, they were ready for the audience, which consisted of Disney employees and their wives.

The response of the audience was extremely positive, and it gave Walt Disney the confidence to move forward and complete the film. He said later in recalling this first viewing:

The effect on our little audience was nothing less than electric. They responded almost instinctively to this union of sound and motion. I thought they were kidding me. So they put me in the audience and ran the action again. It was terrible, but it was wonderful! And it was something new!

Iwerks said: "I've never been so thrilled in my life. Nothing since has ever equaled it."[22]

Walt Disney traveled to New York City to hire a company to produce the soundtrack, since no such facilities existed in Los Angeles. He eventually settled on Pat Powers's Cinephone system,[23] created by Powers using an updated version of Lee De Forest's Phonofilm system, without giving De Forest any credit.[24]

The music in the final soundtrack was performed by the Green Brothers Novelty Band and was conducted by Carl Edouarde. Joe and Lew Green from the band also assisted in timing the music to the film. The first attempt to synchronize the recording with the film, done on September 15, 1928, was a disaster.[25] Disney had to sell his Moon roadster in order to finance a second recording. This was a success, with the addition of a filmed bouncing ball to keep the tempo.[26]

Release and reception

[edit]

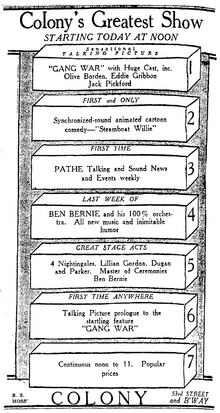

Steamboat Willie premiered at Universal's Colony Theater in New York City on November 18, 1928.[27] The film was distributed by Celebrity Productions, and its initial run lasted two weeks. Disney was paid $500 a week (equivalent to $8,872 in 2023).[26] In its first run, the picture was presented five times a day.[28] It played ahead of the independent feature film Gang War.[4] Steamboat Willie was an immediate hit, while Gang War has since been lost and all but forgotten today.

The success of Steamboat Willie not only led to international fame for Walt Disney but for Mickey as well.

Variety (November 21, 1928) wrote:

Not the first animated cartoon to be synchronized with sound effects, but the first to attract favorable attention. This one represents a high order of cartoon ingenuity, cleverly combined with sound effects. The union brought forth laughs galore. Giggles came so fast at the Colony [Theater] they were stumbling over each other. It's a peach of a synchronization job all the way, bright, snappy, and fit the situation perfectly. Cartoonist, Walter Disney. With most of the animated cartoons qualifying as a pain in the neck, it's a signal tribute to this particular one. If the same combination of talent can turn out a series as good as Steamboat Willie they should find a wide market if the interchangeability angle does not interfere. Recommended unreservedly for all wired houses.[29]

The Film Daily (November 25, 1928) said:

This is what Steamboat Willie has: First, a clever and amusing treatment; secondly, music and sound effects added via the Cinephone method. The result is a real tidbit of diversion. The maximum has been gotten from the sound effects. Worthy of bookings in any house wired to reproduce sound-on-film. Incidentally, this is the first Cinephone-recorded subject to get a public exhibition and at the Colony [Theater], New York, is being shown over Western Electric equipment.[30]

Special honors

[edit]In 1994, members of the animation field voted Steamboat Willie 13th in the book The 50 Greatest Cartoons, which listed the greatest cartoons of all time.[31] In 1998, the short was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[32] The Australian Perth Mint released a 1 kg gold coin in honor of Steamboat Willie in 2015.[33]

Copyright status

[edit]United States

[edit]

Prior to its entrance into the public domain, the film had been the center of a variety of controversies regarding copyright. Its copyright was extended by multiple acts of the United States Congress. Since the copyright was filed in 1928, three days after its initial release,[34] it was extended for nearly a century.[35]

Steamboat Willie could have entered the public domain in four different years: first in 1955,[36] at which point it was renewed to 1986,[37] then extended to 2003 by the Copyright Act of 1976,[38] and finally to 2023 by the Copyright Term Extension Act of 1998 (also known pejoratively as the "Mickey Mouse Protection Act").[39] It has been claimed that these extensions were a response by Congress to extensive lobbying by The Walt Disney Company.[40]

In the 1990s, former Disney researcher Gregory S. Brown determined that the film was likely in the U.S. public domain already due to errors in the original copyright formulation.[41] In particular, the original film's copyright notice had two additional names between Disney and the copyright statement. Thus, under the rules of the Copyright Act of 1909, all copyright claims would be null.[42][41] Arizona State University professor Dennis Karjala suggested that one of his law school students look into Brown's claim as a class project. Lauren Vanpelt took up the challenge and produced a paper agreeing with Brown's claim. She posted her project on the Internet in 1999.[43] Disney later threatened to sue a Georgetown University law student who wrote a paper confirming Brown's claims,[44] alleging that publishing the paper could be slander of title, but Disney chose not to sue after its publication.[45]

Beginning in 2022, several Republican lawmakers vowed to oppose any future attempt to extend the copyright term due to Disney's opposition of the Florida Parental Rights in Education Act. Legal experts noted that later versions of Mickey Mouse created after Steamboat Willie will remain copyrighted, and Disney's use of the Steamboat Willie version as a logo in its films since 2007 may allow them to claim protection for the 1928 version under trademark law, as active trademarks can be renewed in perpetuity (so long as the owner can prove using it).[47][48]

In April 2023, John Oliver announced his intention to use the Steamboat Willie version of Mickey Mouse as the new mascot for Last Week Tonight with John Oliver as soon as the cartoon entered the public domain in 2024, and debuted the "brand new character".[49]

Not affecting trademark status,[50] Steamboat Willie entered the US public domain on January 1, 2024, more than 95 years after its release.[51][52]

Although it was believed that only the black-and-white depiction of Mickey Mouse—which lacks the red shorts and gloves—would enter the public domain, it has been pointed out that a promotional poster created in 1928 features Mickey Mouse wearing red shorts and yellow gloves, meaning those attributes might also now be in the public domain and available for anyone to use.[53][54] However, while the poster was created in 1928, it is unclear whether it was published that same year; thus, its copyright status is unknown, and Mickey Mouse's red shorts and yellow gloves are not definitively in the public domain.[51]

The cartoon has been adapted into two horror films: The Mouse Trap, a slasher film where a mass murderer in a Mickey Mouse mask hunts down a group of teenagers inside an amusement arcade,[55] and Screamboat,[56] a comedy horror film where Mickey Mouse turns into a mutated creature that starts a murderous rampage on a ferry.[55]

Japan

[edit]The copyright status of Steamboat Willie has been more complicated in Japan. Many people believed that the copyright expired in May 1989, based on the regular copyright term of 50 years after publication plus the wartime extension of 10 years and 5 months. In 2003, Japan extended the copyright length for films to 70 years, but it did not revive already expired copyrights. However, films released before 1971 remain under copyright until 38 years after the director dies if it is longer than 70 years after publication.[57] Ub Iwerks, the last surviving director, died in 1971, and counting from 38 years after his death plus the wartime extension, Mickey Mouse entered the public domain in Japan in May 2020. Still, some people alleged that Mickey Mouse would remain protected until 2052 due to the complex nature of the protection for films. [58]

However, according to the Copyright Act of Japan, once the cinematographic work's copyright expires, the original work also loses copyright protection, and the protection for the author's life plus 70 years does not apply to anonymous, corporate or cinematographic works,[59] so it is most likely that the film entered the public domain in May 2020.

In other media

[edit]Television and film

[edit]The fourth-season 1992 episode of The Simpsons "Itchy & Scratchy: The Movie" features a short parody of the opening scene of Steamboat Willie, entitled Steamboat Itchy.[60]

In the 1998 film Saving Private Ryan, set in 1944, a German prisoner of war, nicknamed "Steamboat Willie", tries to win the sympathy of his American captors by talking about Mickey Mouse.[61]

In the 2008 film of the TV series Futurama titled The Beast with a Billion Backs, the opening is a parody of Steamboat Willie.[62]

As part of their 100-year anniversary, in July 2023, Disney released a The Wonderful World of Mickey Mouse special and series finale entitled Steamboat Silly featuring multiple copies of Mickey as he appears in this short.[63][64]

The first cinematic adaption of Steamboat Willie since its entry to public domain was the live-action art film Social Imagineering by multidisciplinary artist Sweætshops released at midnight on January 1, 2024, which was filmed on the PS Waverley paddle steamer.[65]

Video games

[edit]Steamboat Willie–themed levels are featured in the video games Mickey Mania (1994),[66] Kingdom Hearts II (2005),[67] and Epic Mickey (2010).[68] An alternate Steamboat Willie-themed costume of Kingdom Hearts' Sora was featured in Super Smash Bros. Ultimate (2018).[69] The Steamboat Willie versions of Mickey Mouse and Pete are featured as playable racers in Disney Speedstorm (2023).[70][71]

Other use by Disney

[edit]In 1993, to coincide with the opening of Mickey's Toontown in Disneyland, a shortened cover of the cartoon's music was arranged to be featured in the land's background ambiance.[72]

In 2007, a Steamboat Willie clip of Mickey whistling started being used for Walt Disney Animation Studios' production logo.[73][74]

In 2019, Lego released an official Steamboat Willie set to commemorate the 90th anniversary of Mickey Mouse.[75]

The whistle in the film has been used to make sound in the Mickey & Minnie's Runaway Railway attraction, which opened at Disneyland in January 2023.[76]

Release history

[edit]Theatrical

[edit]- July 1928 – first sound test screening (silent with live sound)

- September 1928 – first attempt to synchronize the recording on the film

- November 1928 – original theatrical release with final soundtrack

- 1972 – The Mouse Factory, episode #33: "Tugboats" (TV)

- 1990s – Mickey's Mouse Tracks, episode #45 (TV)

- 1996 – Mickey's Greatest Hits

- 1997 – Ink & Paint Club, episode #2 "Mickey Landmarks" (TV)

- Ongoing – Main Street Cinema at Disneyland

Cuts

[edit]

In the 1950s, Disney removed a scene in which Mickey tugs on the tails of the baby pigs, and then picks up the mother and kicks them off her teats, and plays her like an accordion, since television distributors deemed it inappropriate.[77] A variant of this censored version is featured on the 1998 VHS/Laserdisc compilation special The Spirit of Mickey, where the first part of said scene with Mickey pulling on the piglets' tails is reinstated. Since then, the full version of the film was included on the Walt Disney Treasures DVD set "Mickey Mouse in Black and White", as well as on Disney+ and the Disney website,[78] as well as a plethora of re-uploads after entering the public domain in 2024.

Home media

[edit]- 1984 – Cartoon Classics: Limited Gold Editions: Mickey (VHS)

- 1998 – The Spirit of Mickey (VHS/Laserdisc)

- 2001 – The Hand Behind the Mouse: The Ub Iwerks Story (VHS)

- 2002 – Walt Disney Treasures: Mickey Mouse in Black and White[79]

- 2005 – Vintage Mickey (DVD)

- 2007 – Walt Disney Treasures: The Adventures of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit[80]

- 2009 – Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (Blu-ray)

- 2018 – Celebrating Mickey 90th-anniversary compilation (Blu-ray/DVD/Digital)

- Celebrating Mickey was reissued in 2021 as part of the U.S. Disney Movie Club exclusive The Best of Mickey Collection along with Fantasia and Fantasia 2000 (Blu-ray/DVD/Digital).[81]

- 2019 – Disney+ (streaming online)

- 2023 – Mickey & Minnie: 10 Classic Shorts – Volume 1 95th-anniversary compilation (Blu-ray/DVD/Digital)

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Gerstein, David (2015). Learn to Draw Mickey Mouse & Friends Through the Decades. Walter Foster Jr. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-60058-429-9.

- ^ "Ub Iwerks, Walt Disney. Steamboat Willie. 1928". Museum of Modern Art. Archived from the original on January 1, 2024. Retrieved January 1, 2024.

- ^ "The Mouse and the Maker: How Walt Disney Made Some Noise for the Animation Industry – StMU Research Scholars". Archived from the original on January 1, 2024. Retrieved January 1, 2024.

- ^ a b McGowan, Andrew (April 5, 2023). "Mickey Mouse's Debut Wasn't in 'Steamboat Willie' – It Was in This". Collider. Archived from the original on December 8, 2023. Retrieved January 1, 2024.

- ^ "Biographies of 10 Classic Disney Characters « Disney D23". February 12, 2012. Archived from the original on February 12, 2012. Retrieved September 21, 2024.

- ^ Smith, Dave. "Steamboat Willie" (PDF). Library of Congress. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 6, 2020. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- ^ Op Den Kamp, Claudy; Hunter, Dan, eds. (2019). A History of Intellectual Property in 50 Objects. Cambridge University Press. pp. 171–172. ISBN 9781108352024. Archived from the original on December 30, 2023. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ^ Uytdewilligen, Ryan (2016). The 101 Most Influential Coming-of-age Movies. Algora Publishing. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-1-62894-194-4. Archived from the original on March 20, 2022. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

Buster Keaton's...'last great film' which inspired Mickey Mouse's first cartoon in sound, Steamboat Willie.

- ^ Mouse Planet Archived May 6, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing | Film Registry | National Film Preservation Board | Programs | Library of Congress". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on October 31, 2016. Retrieved January 1, 2024.

- ^ Barrier, Michael (2008). The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney. University of California Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-520-25619-4.

- ^ Gabler, Neal (2006). Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination (1st ed.). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 116. ISBN 9780307265968. Archived from the original on December 26, 2023. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ^ Lazarescu-Thois, Laura (2018). "From Sync to Surround: Walt Disney and its Contribution to the Aesthetics of Music in Animation". The New Soundtrack. 8 (1): 61–72. doi:10.3366/sound.2018.0117. ISSN 2042-8855. Archived from the original on August 13, 2022. Retrieved January 1, 2024.

- ^ Finch, Christopher (1995). The Art of Walt Disney from Mickey Mouse to the Magic Kingdom. New York: Harry N. Abrahms, Inc., Publishers. p. 23. ISBN 0-8109-2702-0.

- ^ Salys, Rimgaila (2009). The Musical Comedy Films of Grigorii Aleksandrov. Intellect. ISBN 9781841502823. OCLC 548664422. Archived from the original on March 20, 2022. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ^ Gould, Stephen Jay (June 7, 1979). Dixon, Bernard (ed.). "Perpetual Youth". New Scientist. Vol. 82, no. 1158. pp. 832–834. ISSN 0028-6664. OCLC 964677385. Retrieved November 21, 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ The New Illustrated Treasury of Disney Songs (5th ed.). Hal Leonard. 1998. ISBN 0-7935-9365-4. OCLC 57245282.

- ^ Mickey Mouse – Steamboat Willie (1928) | Walt Disney | 4K Remastered [Full Movie], January 2024, archived from the original on January 1, 2024, retrieved January 1, 2024

- ^ Korkis, Jim (2014). "More Secrets of Steamboat Willie". In Apgar, Garry (ed.). The Mickey Mouse Reader. University Press of Mississippi. p. 333. ISBN 978-1628461039.

- ^ "Happy 90th Birthday Mickey Mouse: Fun Facts about 'Steamboat Willie'". Archived from the original on September 25, 2023. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- ^ Fanning, Jim (1994). Walt Disney. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 9780791023310.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard (1987). Of Mice and Magic: A History of American Animated Cartoons (Rev. ed.). New York: New American Library. pp. 34–35. ISBN 0-452-25993-2. OCLC 16227115. Archived from the original on March 20, 2022. Retrieved August 7, 2022.

- ^ Lipton, Lenny (2021). The Cinema in Flux: The Evolution of Motion Picture Technology from the Magic Lantern to the Digital Era. Springer Nature. p. 281. ISBN 978-1-0716-0951-4. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ^ Koszarski, Richard (2008). Hollywood on the Hudson: Film and Television in New York from Griffith to Sarnoff. Rutgers University Press. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-8135-4293-5. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ^ Smith, Dave. "Steamboat Willie By Dave Smith, Chief Archivist Emeritus, The Walt Disney Company" (PDF). Loc.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 15, 2017. Retrieved March 13, 2022.

- ^ a b "Steamboat Willie (1928) – The Internet Animation Database". Internet Animation Database. Archived from the original on March 27, 2008.

- ^ "The Broadway Theatre". The Shubert Organization. Archived from the original on November 12, 2012.

The most notable film that played there in the early years was Walt Disney's Steamboat Willie which opened in 1928, and introduced American audiences to an adorable rodent named Mickey Mouse.

- ^ "No Interruption". The Film Daily. Vol. 46, no. 43. New York, Wid's Films and Film Folks, Inc. November 20, 1928. p. 1305. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ^ "Talking Shorts". Variety. Vol. 93, no. 4. November 21, 1928. p. 13. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- ^ "Short Subjects". The Film Daily. Vol. 46, no. 47. November 25, 1928. p. 9. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- ^ Beck, Jerry (1994). The 50 Greatest Cartoons: As Selected by 1,000 Animation Professionals (1st ed.). Turner Publishing. ISBN 978-1878685490. OCLC 30544399.

- ^ "Hooray for Hollywood (December 1998) – Library of Congress Information Bulletin". Loc.gov. Archived from the original on January 12, 2017. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- ^ Mint, Perth (November 27, 2014). "Disney – Steamboat Willie 2015 1 Kilo Gold Proof Coin". Pert Mint. Archived from the original on November 28, 2014. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- ^ Motion pictures, 1912–1939. Library of Congress Copyright Office. 1951. p. 813.

- ^ Fleishman, Glenn (January 1, 2019). "For the First Time in More Than 20 Years, Copyrighted Works Will Enter the Public Domain". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on April 15, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- ^ "Catalog of copyright entries. Ser.3 pt.12–13 v.9–12 1955–1958 Motion Pictures". Catalog of Copyright Entries.musical Compositions. Library of Congress Copyright Office: 373. 1981. OCLC 6467863. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ^ "Titles in document V2207P476". Archived from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved April 19, 2022.

163 Steamboat Willie / R162021 (1955)

- ^ Douglas, Jacob (January 14, 2021). "Free (Steamboat) Willie: How Walt Disney's Original Mouse Could be Entering the Public Domain: Pondering The Fate Of KC-Inspired Intellectual Property". Flatland. Archived from the original on February 26, 2022. Retrieved April 10, 2022.

- ^ Lessig, Lawrence. "Copyright's First Amendment". UCLA Law Review. 48 (5): 1057–1073. ISSN 0041-5650.

- ^ Lessig, Lawrence (2004). Free Culture: How Big Media Uses Technology and the Law to Lock Down Culture and Control Creativity. New York: Penguin Press. p. 220. ISBN 1-59420-006-8. OCLC 53324884.

- ^ a b Menn, Joseph (August 22, 2008). "Disney's rights to young Mickey Mouse may be wrong". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 21, 2009. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- ^ "An Act to Amend and Consolidate the Act Respecting Copyright" (PDF). 1909. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 27, 2017. Retrieved January 1, 2024.

- ^ Vanpelt, Lauren (Spring 1999). "Mickey Mouse – A Truly Public Character". Archived from the original on October 2, 2008. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- ^ Hedenkamp, Douglas A. (Spring 2003). "Free Mickey Mouse: Copyright Notice, Derivative Works, and the Copyright Act of 1909". Virginia Sports & Entertainment Law Journal (2). Archived from the original on July 25, 2008. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- ^ Masnick, Mike (August 25, 2008). "Turns Out Disney Might Not Own The Copyright On Early Mickey Mouse Cartoons". Techdirt. Archived from the original on October 23, 2020. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

Disney warned him that publishing his research could be seen as 'slander of title' suggesting that he was inviting a lawsuit. He still published and Disney did not sue.

- ^ Patten, Dominic (January 1, 2024). "Mickey Mouse Hits The Public Domain, But Don't Expect To Get A Free Ride On 'Steamboat Willie'". Deadline. Archived from the original on January 2, 2024. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ Martín, Hugo (May 11, 2022). "Republicans took away Disney's special status in Florida. Now they're gunning for Mickey himself". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 11, 2022. Retrieved January 22, 2023.

- ^ Barnes, Brooks (December 27, 2022). "Mickey's Copyright Adventure: Early Disney Creation Will Soon Be Public Property". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 25, 2023. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ^ Tinoco, Armando (April 2, 2023). "John Oliver Tests Disney's Lawyers By Staking Claim On Mickey Mouse Ahead Of 'Steamboat Willie' Version Entering Public Domain". Deadline. Archived from the original on May 22, 2023. Retrieved April 3, 2023.

- ^ Lee, Timothy B. (January 1, 2019). "Mickey Mouse will be public domain soon – here's what that means". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on January 2, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- ^ a b Jenkins, Jennifer. "Mickey, Disney, and the Public Domain: a 95-year Love Triangle". web.law.duke.edu. Duke Center for the Study of the Public Domain. Archived from the original on January 1, 2024. Retrieved January 1, 2024.

- ^ Delouya, Samantha (January 1, 2024). "An early version of Mickey Mouse is now in the public domain | CNN Business". CNN. Archived from the original on January 1, 2024. Retrieved January 1, 2024.

- ^ Bolling, Ruben (January 2, 2024). "Mickey Mouse's red shorts have entered the public domain". Boing Boing. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ "Mickey Mouse poster from 1928 sells for more than $100,000". Reuters. November 29, 2012. Retrieved September 3, 2024.

- ^ a b Maddaus, Gene (January 2, 2024). "'Steamboat Willie' Horror Film Announced as Mickey Mouse Enters Public Domain". Variety. Retrieved January 4, 2024.

- ^ "Untitled Steamboat Willie Horror Film – IMDb". IMDb. Retrieved January 4, 2024.

- ^ "Argument for the Extension of the Copyright Protection over Cinematographic Works". Archived from the original on February 4, 2008. Retrieved March 14, 2008.

- ^ https://xtrend.nikkei.com/atcl/contents/skillup/00009/00073/

- ^ [https://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/en/laws/view/4207 Copyright Act (Act No. 48 of May 6, 1970 amended up to Act No. 52 of 2021)

- ^ Martyn, Warren; Wood, Adrian (2000). "Itchy & Scratchy: The Movie". BBC. Archived from the original on September 4, 2014. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ^ Ryan, Jeff (2018). "36: Overlord". A Mouse Divided: How Ub Iwerks Became Forgotten, and Walt Disney Became Uncle Walt. Post Hill Press. ISBN 9781682616284. Archived from the original on December 30, 2023. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ^ "Futurama: 'Reincarnation' (6.26)". Paste. September 9, 2011. Archived from the original on June 6, 2023. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ^ Carter, Justin (July 29, 2023). "Disney's Beloved Mickey Mouse Shorts End Their Decade-Long Run". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on December 24, 2023. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ^ Mullinax, Hope (November 19, 2023). "Disney Celebrates Mickey Mouse's 95th Birthday With a Special Tribute Video". Collider. Archived from the original on December 26, 2023. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ^ "Mickey Mouse 'Steamboat Willie' feature filmed on Waverley". Greenock Telegraph. January 13, 2023. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ^ O'Neill, Jamie (December 14, 2010). "Mickey Mania Review (SNES)". Nintendo Life. Archived from the original on September 25, 2023. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ^ Mejia, Ozzie (April 15, 2018). "Kingdom Hearts 3 Goes Retro with Classic Kingdom". Shacknews. Archived from the original on July 23, 2018. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ^ Tong, Sophia (July 26, 2010). "Peter David penning Epic Mickey digicomic, graphic novel". GameSpot. Archived from the original on March 23, 2014. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ^ Kamen, Matt (October 5, 2021). "'Kingdom Hearts' hero Sora is the final 'Super Smash Bros Ultimate' DLC fighter". NME. Archived from the original on March 30, 2023. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ^ Ford, Suzie (May 26, 2023). "Steamboat Pete Cruising into Disney Speedstorm in Season 2". GameSpace. Archived from the original on January 2, 2024. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ Penwell, Chris (September 24, 2023). "All Disney Speedstorm characters so far". Destructoid. Archived from the original on January 2, 2024. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ Steamboat Willie (From "Toontown"), October 26, 2018, archived from the original on January 1, 2024, retrieved January 2, 2024

- ^ Osmond, Andrew (2022). 100 Animated Feature Films (rev. ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 3. ISBN 9781839024443. Archived from the original on December 30, 2023. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ^ Maddaus, Gene (December 22, 2023). "Mickey Mouse, Long a Symbol in Copyright Wars, to Enter Public Domain: 'It's Finally Happening'". Variety. Archived from the original on December 24, 2023. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ^ Anderton, Ethan (March 18, 2019). "Cool Stuff: Disney's Classic 'Steamboat Willie' Mickey Mouse Short Is Becoming A LEGO Set". /Film. Archived from the original on December 26, 2023. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ^ Palm, Iman (January 27, 2023). "What to expect with Mickey & Minnie's Runaway Railway ride at Disneyland". KTLA. Archived from the original on December 26, 2023. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ^ Korkis, Jim (November 14, 2012). "Secrets of Steamboat Willie". Mouseplanet.com. Archived from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- ^ Steamboat Willie, archived from the original on January 4, 2024, retrieved January 8, 2024

- ^ "Mickey Mouse in Black and White DVD Review". DVD Dizzy. Archived from the original on March 1, 2021. Retrieved February 19, 2021.

- ^ "The Adventures of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit DVD Review". DVD Dizzy. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ "The Best of Mickey Collection Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on May 23, 2021. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

External links

[edit]- Steamboat Willie on YouTube (edited version; official upload by Walt Disney Animation Studios)

- Steamboat Willie at IMDb

- Steamboat Willie at Disney A to Z

- Steamboat Willie at the TCM Movie Database

- Steamboat Willie at The Encyclopedia of Disney Animated Shorts

- Steamboat Willie at the Internet Archive

- The Test Screening of Steamboat Willie

Essays

[edit]- Steamboat Willie essay by Dave Smith, Chief Archivist Emeritus, The Walt Disney Company at National Film Registry

- Steamboat Willie essay by Daniel Eagan in America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry, A&C Black, 2010 ISBN 0826429777, pp. 152–153

- Mickey, Disney, and the Public Domain: a 95-year Love Triangle essay by Jennifer Jenkins, Director, Duke Center for the Study of the Public Domain

- 1928 films

- 1928 American animated short films

- 1920s Disney animated short films

- 1920s English-language films

- 1920s musical comedy films

- 1928 comedy films

- Internet memes introduced in 2024

- American animated black-and-white films

- American musical comedy films

- Animated films about mice

- Animated films about cats

- Animated films about birds

- Animated films set on ships

- Animated films without speech

- Early sound films

- Films directed by Ub Iwerks

- Films directed by Walt Disney

- Films produced by Walt Disney

- Films set on boats

- Mickey Mouse short films

- United States National Film Registry films

- English-language comedy short films

- English-language musical comedy films

- 1928 musical films

- American musical short films