Splenic infarction

| Splenic infarction | |

|---|---|

| |

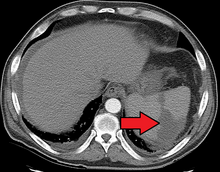

| Splenic infarct seen on CT | |

| Specialty | General surgery |

Splenic infarction is a condition in which blood flow supply to the spleen is compromised,[1] leading to partial or complete infarction (tissue death due to oxygen shortage) in the organ.[2] Splenic infarction occurs when the splenic artery or one of its branches are occluded, for example by a blood clot.[3]

In one series of 59 patients, mortality amounted to 5%.[3] Complications include a ruptured spleen, bleeding, an abscess of the spleen (for example, if the underlying cause is infective endocarditis) or pseudocyst formation. Splenectomy may be warranted for persistent pseudocysts due to the high risk of subsequent rupture.[4]

Diagnosis

[edit]Although it can occur asymptomatically, the typical symptom is severe pain in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen, sometimes radiating to the left shoulder. Fever and chills develop in some cases.[3] It has to be differentiated from other causes of acute abdomen.

An abdominal CT scan is the most commonly used modality to confirm the diagnosis,[3] although abdominal ultrasound can also contribute.[5][6][7]

Treatment

[edit]There is no specific treatment, except treating the underlying disorder and providing adequate pain relief. Surgical removal of the spleen (splenectomy) is only required if complications ensue; surgical removal predisposes to overwhelming post-splenectomy infections.[8]

Causes

[edit]

Several factors may increase the tendency for clot formation, such as specific infections (such as infectious mononucleosis,[9] [dubious – discuss][better source needed] cytomegalovirus infection,[10] malaria,[11] or babesiosis[12]), inherited clotting disorders (thrombophilia, such as Factor V Leiden, antiphospholipid syndrome), malignancy (such as pancreatic cancer) or metastasis, or a combination[13] of these factors.

In some conditions, blood clots form in one part of the circulatory system and then dislodge and travel to another part of the body, which could include the spleen. These emboligenic disorders include atrial fibrillation, patent foramen ovale, endocarditis or cholesterol embolism.

Splenic infarction is also more common in hematological disorders with associated splenomegaly, such as the myeloproliferative disorders. Other causes of splenomegaly (for example, Gaucher disease or hemoglobinopathies) can also predispose to infarction. Splenic infarction can also result from a sickle cell crisis in patients with sickle cell anemia. Both splenomegaly and a tendency towards clot formation feature in this condition. In sickle cell disease, repeated splenic infarctions lead to a non-functional spleen (autosplenectomy).

Any factor that directly compromises the splenic artery can cause infarction. Examples include abdominal traumas, aortic dissection, torsion of the splenic artery (for example, in wandering spleen) or external compression on the artery by a tumor. It can also be a complication of vascular procedures.[14]

Splenic infarction can be due to vasculitis or disseminated intravascular coagulation. Various other conditions have been associated with splenic infarction in case reports, for example granulomatosis with polyangiitis[15] or treatment with medications that predispose to vasospasm or blood clot formation, such as vasoconstrictors used to treat esophageal varices, sumatriptan[16] or bevacizumab.[17]

In a single-center retrospective cases review, people who were admitted to the hospital with a confirmed diagnosis of acute splenic infarction, cardiogenic emboli was the dominant etiology followed by atrial fibrillation, autoimmune disease, associated infection, and hematological malignancy.[18] In spite of those already had risk factors of developing splenic infarction, there were nine beforehand healthy people. And among them, 5 of 9 hitherto silent antiphospholipid syndrome or mitral valve disease had been identified.[18] Two remained cryptogenic.[18]

Therapeutic infarction

[edit]Splenic infarction can be induced for the treatment of such conditions as portal hypertension or splenic injury.[19] It can also be used prior to splenectomy for the prevention of blood loss.

References

[edit]- ^ Chapman, J; Bhimji, SS (2018), "article-29380", Splenic Infarcts, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 28613652, retrieved 2019-02-27

- ^ Jaroch MT, Broughan TA, Hermann RE (October 1986). "The natural history of splenic infarction". Surgery. 100 (4): 743–50. PMID 3764696.

- ^ a b c d Nores M, Phillips EH, Morgenstern L, Hiatt JR (February 1998). "The clinical spectrum of splenic infarction". Am Surg. 64 (2): 182–8. PMID 9486895.

- ^ Pachter HL, Hofstetter SR, Elkowitz A, Harris L, Liang HG (September 1993). "Traumatic cysts of the spleen--the role of cystectomy and splenic preservation: experience with seven consecutive patients". J Trauma. 35 (3): 430–6. doi:10.1097/00005373-199309000-00016. PMID 8371303.

- ^ Görg C, Seifart U, Görg K (2004). "Acute, complete splenic infarction in cancer patient is associated with a fatal outcome". Abdom Imaging. 29 (2): 224–7. doi:10.1007/s00261-003-0108-9. PMID 15290950. S2CID 31332720.

- ^ O'Keefe JH, Holmes DR, Schaff HV, Sheedy PF, Edwards WD (December 1986). "Thromboembolic splenic infarction". Mayo Clin. Proc. 61 (12): 967–72. doi:10.1016/s0025-6196(12)62638-x. PMID 3773568.

- ^ Frippiat F, Donckier J, Vandenbossche P, Stoffel M, Boland B, Lambert M (1996). "Splenic infarction: report of three cases of atherosclerotic embolization originating in the aorta and retrospective study of 64 cases". Acta Clin Belg. 51 (6): 395–402. doi:10.1080/22953337.1996.11718537. PMID 8997756.

- ^ Salvi PF, Stagnitti F, Mongardini M, Schillaci F, Stagnitti A, Chirletti P (2007). "Splenic infarction, rare cause of acute abdomen, only seldom requires splenectomy. Case report and literature review". Ann Ital Chir. 78 (6): 529–32. PMID 18510036.

- ^ Suzuki Y, Shichishima T, Mukae M, et al. (June 2007). "Splenic infarction after Epstein-Barr virus infection in a patient with hereditary spherocytosis". Int. J. Hematol. 85 (5): 380–3. doi:10.1532/IJH97.07208. PMID 17562611. S2CID 36770769.

- ^ Rawla, P; Vellipuram, AR; Bandaru, SS; Raj, JP (2017). "Splenic Infarct and Pulmonary Embolism as a Rare Manifestation of Cytomegalovirus Infection". Case Reports in Hematology. 2017: 1850821. doi:10.1155/2017/1850821. PMC 5660763. PMID 29158925.

- ^ Bonnard P, Guiard-Schmid JB, Develoux M, Rozenbaum W, Pialoux G (January 2005). "Splenic infarction during acute malaria". Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 99 (1): 82–6. doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2004.06.005. PMID 15550267.

- ^ Florescu D, Sordillo PP, Glyptis A, et al. (January 2008). "Splenic infarction in human babesiosis: two cases and discussion". Clin. Infect. Dis. 46 (1): e8–11. doi:10.1086/524081. PMID 18171204.

- ^ Breuer C, Janssen G, Laws HJ, et al. (December 2008). "Splenic infarction in a patient hereditary spherocytosis, protein C deficiency and acute infectious mononucleosis". Eur. J. Pediatr. 167 (12): 1449–52. doi:10.1007/s00431-008-0781-3. PMID 18604554. S2CID 2702794.

- ^ Almeida JA, Riordan SM (2008). "Splenic infarction complicating percutaneous transluminal coeliac artery stenting for chronic mesenteric ischaemia: a case report". J Med Case Rep. 2: 261. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-2-261. PMC 2533016. PMID 18684317.

- ^ Langlois, V; Lesourd, A; Girszyn, N; Ménard, JF; Levesque, H; Caron, F; Marie, I (January 2016). "Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibodies Associated With Infective Endocarditis". Medicine (Baltimore). 95 (3): e2564. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000002564. PMC 4998285. PMID 26817911.

- ^ Arora A, Arora S (September 2006). "Spontaneous splenic infarction associated with sumatriptan use". J Headache Pain. 7 (4): 214–6. doi:10.1007/s10194-006-0291-5. PMC 3476041. PMID 16767537.

- ^ Malka D, Van den Eynde M, Boige V, Dromain C, Ducreux M (December 2006). "Splenic infarction and bevacizumab". Lancet Oncol. 7 (12): 1038. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70980-9. PMID 17138227.

- ^ a b c Ami, S; Meital, A; Ella, K; Abraham, K (2015-09-11). "Acute Splenic Infarction at an Academic General Hospital Over 10 Years: Presentation, Etiology, and Outcome". Medicine. 94 (36): e1363. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000001363. PMC 4616622. PMID 26356690.

- ^ Haan JM, Bochicchio GV, Kramer N, Scalea TM (March 2005). "Nonoperative management of blunt splenic injury: a 5-year experience". J Trauma. 58 (3): 492–8. doi:10.1097/01.TA.0000154575.49388.74. PMID 15761342.