Spanish battleship Jaime I

Jaime I, c. 1931

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Jaime I |

| Namesake | James I of Aragon |

| Builder | SECN, Naval Dockyard, El Ferrol, Spain |

| Laid down | 5 February 1912 |

| Launched | 21 September 1914 |

| Completed | 20 December 1921 |

| Fate | Wrecked by accidental explosion 17 June 1937; refloated, but discarded 3 July 1939 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | España-class battleship |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 140 m (459 ft 4 in) o/a |

| Beam | 24 m (78 ft 9 in) |

| Draft | 7.8 m (25 ft 7 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 19.5 knots (36.1 km/h) |

| Range | 5,000 nmi (9,300 km) at 10 knots (19 km/h) |

| Complement | 854 |

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

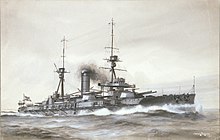

Jaime I was a Spanish dreadnought battleship, the third and final member of the España class, which included two other ships: España and Alfonso XIII. Named after King James I of Aragon, Jaime I was built in the early 1910s, though her completion was delayed until 1921 owing to a shortage of materials that resulted from the start of World War I in 1914. The class was ordered as part of a naval construction program to rebuild the fleet after the losses of the Spanish–American War in the context of closer Spanish relations with Britain and France. The ships were armed with a main battery of eight 305 mm (12 in) guns and were intended to support the French Navy in the event of a major European war.

By the time Jaime I was completed, the Rif War had broken out in the Spanish protectorate in Morocco and the ship was used to support Spanish forces fighting in the colony in the early to mid-1920s. She was placed in reserve in 1931 after the proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic, but was reactivated in 1933 to serve as the fleet flagship. Plans to modernize the vessel in the mid-1930s came to nothing after the start of the Spanish Civil War in July 1936. Jaime I and the bulk of the fleet remained loyal to the republican government, though her sister Alfonso XIII (by then having been renamed España), fell under rebel control. The Spanish Republican Navy nevertheless failed to make effective use of its naval superiority and Jaime I did not see significant action apart from bombarding Nationalist positions in North Africa. She was attacked twice by enemy aircraft during the war, and in June 1937, an accidental fire aboard the ship caused an internal explosion that destroyed the ship. Some of her guns were salvaged and mounted in coastal batteries after the war and remain extant, though no longer in use.

Design

[edit]

Following the destruction of much of the Spanish fleet in the Spanish–American War of 1898, the Spanish Navy made a series of failed attempts to begin the process of rebuilding. After the First Moroccan Crisis strengthened Spain's ties to Britain and France and public support for rearmament increased in its aftermath, the Spanish government came to an agreement with those countries for a plan of mutual defense. In exchange for British and French support for Spain's defense, the Spanish fleet would support the French Navy in the event of war with the Triple Alliance. A strengthened Spanish fleet was thus in the interests of Britain and France, which accordingly provided technical assistance in the development of modern warships, the contracts for which were awarded to the firm Spanish Sociedad Española de Construcción Naval (SECN), which was formed by the British shipbuilders Vickers, Armstrong Whitworth, and John Brown & Company. The vessels were authorized some six months after the British had completed the "all-big-gun" HMS Dreadnought, and after discarding plans to build pre-dreadnought-type battleships, the naval command quickly decided to build their own dreadnoughts.[1]

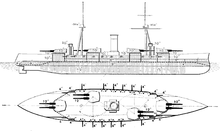

Jaime I was 132.6 m (435 ft) long at the waterline and 140 m (459 ft 4 in) long overall. She had a beam of 24 m (78 ft 9 in) and a draft of 7.8 m (25 ft 7 in); her freeboard was 15 ft (4.6 m) amidships. The ship displaced 15,700 t (15,500 long tons) as designed and up to 16,450 t (16,190 long tons) at full load. Her propulsion system consisted of four-shaft Parsons steam turbines driving four screw propellers, with steam provided by twelve Yarrow boilers. The engines were rated at 15,500 shaft horsepower (11,600 kW) and produced a top speed of 19.5 knots (36.1 km/h; 22.4 mph). Jaime I had a cruising radius of 5,000 nautical miles (9,300 km; 5,800 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). Her crew consisted of 854 officers and enlisted men.[2]

Jaime I was armed with a main battery of eight 305 mm (12 in) 50-caliber guns, mounted in four twin gun turrets. One turret was placed forward, two were positioned en echelon amidships, and the fourth was aft of the superstructure.[2] This mounting scheme was chosen in preference to superfiring turrets, as was done in the American South Carolina-class battleships, to save weight and cost.[3] For defense against torpedo boats, she carried a secondary battery that consisted of twenty 102 mm (4 in) guns mounted individually in casemates along the length of the hull. They were too close to the waterline, however, which made them unusable in heavy seas. She was also armed with four 3-pounder guns and two machine guns. Her armored belt was 203 mm (8 in) thick amidships; the main battery turrets were protected with the same amount of armor plate. The conning tower had 254 mm (10 in) thick sides. Her armored deck was 38 mm (1.5 in) thick.[2]

Service history

[edit]Construction and the Rif War

[edit]

Jaime I, named for the 13th century James I of Aragon,[4] was laid down at the SECN shipyard in Ferrol on 5 February 1912. She was launched on 21 September 1914, less than two months after the start of World War I. Spain remained neutral during the conflict, but because Britain supplied much of the armament and other building materials, work on Jaime I was considerably delayed. She was largely complete by early 1915, by which time she only lacked her main battery guns and mounts, which could not be delivered owing to the war. She underwent initial machinery testing in May 1915, and the ship was ready to go to sea by 1917, but she was not completed until well after the end of the war. She conducted sea trials in May 1921, slightly exceeding 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph) on speed tests, and work was finally finished on 20 December.[2][5] Upon her completion, she joined her two sister ships in the 1st Squadron of the Spanish fleet.[6][7]

Throughout the early 1920s, she provided fire support to the Spanish Army in its campaigns in Morocco during the Rif War that had broken out in mid-1921. Her sister ship España was wrecked during operations off Morocco in 1923. During this period, tensions over the European colonial holdings in North Africa—predominantly stoked by Italy's fascist leader Benito Mussolini over the perceived lack of prizes for Italy's eventual participation in World War I on the side of Britain and France—had led to a rapprochement between Italy and Spain in 1923, which was at that time ruled by the dictator Miguel Primo de Rivera. Primo de Rivera sent a fleet consisting of Jaime I, her sister Alfonso XIII, the light cruiser Reina Victoria Eugenia, two destroyers, and four submarines to visit the Italian fleet in late 1923. They departed Valencia on 16 November and stopped in La Spezia and Naples, arriving back in Barcelona on 30 November.[8]

Rif insurgents operating a coastal artillery battery damaged Jaime I in 1924.[9] By 1925, the Rif rebels had widened the war by attacking French positions in neighboring French Morocco. Spain and France planned a major landing at Alhucemas, consisting of some 13,000 soldiers, 11 tanks, and 160 aircraft, to attack the core rebel territory in September. The Spanish Navy supplied Jaime I, Alfonso XIII, four cruisers, a seaplane tender, and several smaller craft. The French added the battleship Paris, two cruisers, and several other vessels. Both fleets provided gunfire support as the ground forces landed on 8 September; the amphibious assault was a success, and after heavy fighting over the next two years, the Rifian rebels were defeated.[10] In the final days of the conflict in October 1927, Alfonso XIII, his wife, and a number of generals, including Primo de Rivera, Francisco Franco, Dámaso Berenguer, and Ricardo Burguete, traveled to Morocco to tour the pacified colony. They came aboard Jaime I at Algeciras, Spain and crossed to Ceuta in Morocco on 5 October. After completing their tour, they returned to the ship on 10 October to be taken back to Spain.[11]

Early 1930s

[edit]By the early 1930s, the effects of the Great Depression had spurred significant domestic opposition to the regime of Primo de Rivera, leading to his resignation on 28 January, and ultimately to Alfonso XIII's exile in April 1931. Immediately thereafter, the government of the Second Spanish Republic began a series of cost-cutting measures to offset the deficits that had been incurred during the Rif War, and as a result, both España and Jaime I were placed in reserve in Ferrol on 15 June. Jaime I was recommissioned on 20 April 1933 to serve as the fleet flagship. Plans to modernize the España-class battleships traced their origin to the 1920s, but the increased risk of conflict with Italy by the mid-1930s put increased pressure to begin the work.[12] One proposal, advanced in 1934, advocated rebuilding the ships into analogues to the German Deutschland-class cruisers with new oil-fired boilers. The ships' hulls would have been lengthened, and the main battery turrets rearranged so they would all be on the centerline. The ships' secondary batteries would have been replaced with dual-purpose (DP) 120 mm (4.7 in) guns. The plan ultimately came to nothing.[13]

The finalized plan for Jaime I and España involved increasing the height of the wing turrets' barbettes, improving their fields of fire and allowing them to fire over the new secondary battery, which was to consist of twelve 120 mm DP guns placed on the upper deck in open mounts. A new anti-aircraft battery of either ten 25 mm (1 in) or eight 40 mm (1.6 in) guns were to be fitted. Other changes were to be made to improve fire-control systems, increase crew accommodation spaces, and install anti-torpedo bulges, among other improvements. Work on both vessels was slated to begin in early 1937, but the scheduled modernization was interrupted by the Spanish coup of July 1936, which plunged the country into the Spanish Civil War.[14]

Spanish Civil War

[edit]

In mid-July 1936, Jaime I was moored in Vigo; she was at that time the only battleship capable of going to sea, as her sister España was being repaired in Ferrol.[15] Franco, the leader of the Nationalist coup against the government, relied on defections from the Navy to carry the Army of Africa to Spain. The ships' crews in Ferrol already knew about the plans by 13 July, and many attended a meeting that day to discuss what course of action they would take if the officer corps joined Franco when he launched the coup. On the morning of 18 July, wireless operators in the navy headquarters Madrid intercepted radio messages from Franco to rebels in Morocco; they alerted naval headquarters, which in turn sent messages to every ship in the fleet to alert the crews to watch for rebellious officers. The crews in Cartagena, including Jaime I, mutinied after their commanders began to join the Nationalists, murdering many of them and ensuring the ships would remain under government control in the Spanish Republican Navy.[16][17] Jaime I avoided the worst of the bloodshed, as her commander opted to remain loyal to the government.[18]

Jaime I got underway on 19 July to attempt to block the crossing, joining other elements of the fleet off Gibraltar later that day.[19] Despite the fact that the Republican government had retained most of the fleet in the Mediterranean, it was unable to block the passage of the Army of Africa to Spain. The vessels were crippled by poor discipline for some time, as they had had few remaining officers and the crews distrusted those that were not killed. In addition, the German Kriegsmarine (War Navy) had sent the heavy cruisers Deutschland and Admiral Scheer to protect the convoys of transport ships that carried heavy weapons. And significant numbers of soldiers were carried by Junkers Ju 52 transport aircraft covertly supplied by the Nazis through the dummy corporation Sociedad Hispano-Marroquí de Transportes (Spanish-Moroccan Transport Company).[20]

In the first months of the war, Jaime I shelled a number of rebel strongholds, among them Ceuta, Melilla, and Algeciras. In Algeciras, she scored hits with her secondary armament on the Nationalist gunboat Eduardo Dato, which was burned down to the waterline,[21] although she was later repaired and returned to service.[22] On 13 August, Jaime I was damaged by a Nationalist air attack at Málaga; a pair of bombers from the German Condor Legion attacked the vessel early that morning. They scored a hit with a small bomb that struck the ship in the bow and caused minimal damage.[23][24]

The elements of the Spanish fleet that had been moored in Ferrol were seized by Nationalist forces at the start of the revolt; these ships included España, which was used to enforce a blockade of the northern Spanish ports of Gijón, Santander, and others. In response to these operations, the Republicans deployed a flotilla of five submarines from the Mediterranean, though one was sunk by Nationalist forces en route. They also briefly deployed Jaime I, a pair of light cruisers, and six destroyers to Gijón, arriving on 25 September.[25]

On 2 October, sailors from Jaime I, having learned that the destroyer Almirante Ferrándiz had been sunk by the Nationalists, took revenge by marching to the prison ship Cabo Quilates in the estuary of Bilbao and executing dozens of prisoners who had been arrested for sympathies with the rebels. Some of the sailors were in turn executed by the Basque Government and the battleship was ordered to leave the port of Bilbao.[26][27]

The squadron departed already on 13 October without having attacked España or any other elements of the Nationalist fleet. For their part, the Nationalists avoided confronting the Republican ships, owing in large part to the significantly better condition of Jaime I compared to España, the latter having only three of her four turrets in operation.[25] When the Republican ships departed, they left behind two of the submarines and one of the destroyers, and some of Jaime I's secondary guns were dismounted, later to be installed on four fishing boats.[28]

In early 1937, Jaime I was dry docked in Cartagena for repairs after a recent grounding. A group of five Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 bombers of the Italian Aviazione Legionaria attacked on 21 May after she had been re-floated. Republican anti-aircraft fire was ineffective and failed to prevent the bombers from making two runs on the ship, dropping around sixty 100 kg (220 lb) bombs in total. Reports of their success vary; Albert Nofi states that they scored three hits that caused only minor damage, while Marco Mattioli states that the attack resulted in two hits, two near misses on her starboard side and three more on the quay to which she was moored, disabling the ship.[23][29]

On 17 June, while at Cartagena, she was destroyed by an accidental internal explosion and fire, although sabotage was suspected.[2][30] Some 200 men were killed in the explosion.[31] She was refloated, but determined to be beyond repair. She was officially discarded on 3 July 1939 and was subsequently broken up for scrap.[2][30] All the guns were recovered from the wreck and were erected in coastal artillery batteries in 1940 near Tarifa to cover the Strait of Gibraltar. Four of her guns, from the fore and aft turrets, were mounted two apiece at the Vigia Battery (D-9) and the Cascabel Battery (D-10). Each battery consisted of a concrete emplacement that included a magazine and a separate command post. Both batteries were abandoned in 1985 but are still present, albeit in a state of degradation owing to a lack of maintenance.[32][33]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Rodríguez González, pp. 268–273.

- ^ a b c d e f Sturton, p. 378.

- ^ Fitzsimons, p. 856.

- ^ Rodríguez González, p. 282.

- ^ Hall, p. 504.

- ^ Sturton, pp. 375–376.

- ^ Garzke & Dulin, p. 438.

- ^ Rodríguez González, pp. 283–284.

- ^ Miller, p. 131.

- ^ Rodríguez González, p. 284.

- ^ Alvarez, pp. 205–206.

- ^ Rodríguez González, pp. 283–285.

- ^ Garzke & Dulin, pp. 438–439.

- ^ Rodríguez González, pp. 285–286.

- ^ Thomas, p. 231.

- ^ Beevor, pp. 71–73.

- ^ Salvadó, p. 224.

- ^ Thomas, p. 232.

- ^ Thomas, pp. 231–232.

- ^ Beevor, p. 73.

- ^ Alpert, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Sturton, p. 381.

- ^ a b Nofi, p. 32.

- ^ Proctor, p. 28.

- ^ a b Rodríguez González, pp. 287–288.

- ^ "Buque-prisión Cabo Quilates". Visit Barakaldo (in European Spanish). Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ^ Cortabarría Igartua, Germán. "CABO QUILATES". Auñamendi Encyclopedia (in Spanish). Eusko Ikaskuntza. Retrieved 15 July 2022. It puts the assault on 25 September.

- ^ Beevor, pp. 226–227.

- ^ Mattioli, p. 11.

- ^ a b Gibbons, p. 195.

- ^ Rodríguez González, p. 289.

- ^ McGovern, p. 179.

- ^ Alcázar García, p. 14.

References

[edit]- Alcázar García, César Sanchez (14 November 2007). "La Batería de Vigía" [The Vigia Battery] (PDF). Aljaranda: Revista de estudios tarifeños (in Spanish) (65). Ayuntamiento de Tarifa: 4. ISSN 1130-7986. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- Alpert, Michael (2008). La guerra civil española en el mar [The Spanish Civil War at Sea] (in Spanish). Barcelona: Editorial Critica. ISBN 978-84-8432-975-6.

- Alvarez, Jose (2001). The Betrothed of Death: The Spanish Foreign Legion During the Rif Rebellion, 1920–1927. Westport: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-07341-0.

- Beevor, Antony (2006). The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939. New York: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-297-84832-5.

- Fitzsimons, Bernard (1978). "España". The Illustrated Encyclopedia of 20th Century Weapons and Warfare. Vol. 8. Milwaukee: Columbia House. pp. 856–857. ISBN 978-0-8393-6175-6.

- Gibbons, Tony (1983). The Complete Encyclopedia of Battleships and Battlecruisers: A Technical Directory of All the World's Capital Ships From 1860 to the Present Day. London: Salamander Books Ltd. ISBN 978-0-86101-142-1.

- Garzke, William; Dulin, Robert (1985). Battleships: Axis and Neutral Battleships in World War II. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-101-0.

- Hall, R. A. (1922). Robinson, F. M. (ed.). "Professional Notes". United States Naval Institute Proceedings. 48 (1). Annapolis: Naval Institute Press: 455–506. OCLC 682045948.

- Mattioli, Marco (2014). Savoia-Marchetti S.79 Sparviero Torpedo-Bomber Units. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-78200-809-5.

- McGovern, Terrance (2009). "The Spanish Coast Artillery of the Strait of Gibraltar". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2009. London: Conway. pp. 177–182. ISBN 978-1-84486-089-0.

- Miller, David (2001). Illustrated Directory of Warships of the World. Osceola: MBI Pub. Co. ISBN 978-0-7603-1127-1.

- Nofi, Albert A. (2010). To Train The Fleet For War: The U.S. Navy Fleet Problems, 1923–1940. Washington, DC: Naval War College Press. ISBN 978-1-88-473387-1.

- Proctor, Raymond L. (1983). Hitler's Luftwaffe in the Spanish Civil War. London: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-22246-7.

- Rodríguez González, Agustín Ramón (2018). "The Battleship Alfonso XIII (1913)". In Taylor, Bruce (ed.). The World of the Battleship: The Lives and Careers of Twenty-One Capital Ships of the World's Navies, 1880–1990. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. pp. 268–289. ISBN 978-0-87021-906-1.

- Salvadó, Francisco J. Romero (2013). Historical Dictionary of the Spanish Civil War. Lanham: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8108-8009-2.

- Sturton, Ian (1985). "Spain". In Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 375–382. ISBN 978-0-85177-245-5.

- Thomas, Hugh (2001) [1961]. The Spanish Civil War: Revised Edition. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 978-0-375-75515-6.