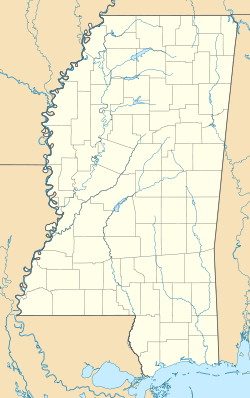

Skipwith's Landing, Mississippi

Skipwith's Landing, Mississippi | |

|---|---|

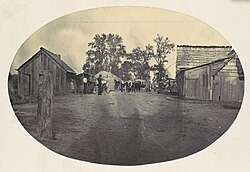

Skipwith's Landing, 1864 (Metropolitan Museum of Art) | |

| Coordinates: 32°58′58″N 91°05′20″W / 32.98278°N 91.08889°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Mississippi |

| County | Issaquena |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

Skipwith's Landing was a 19th-century boat landing and human settlement on the east bank of the Mississippi River, located in the county of Issaquena in the U.S. state of Mississippi.[1][2] Skipwith's Landing was situated about 55 mi (89 km) to 100 mi (160 km) north of Vicksburg, Mississippi, depending on mode of travel.[3][4]

History

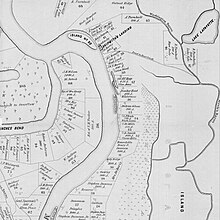

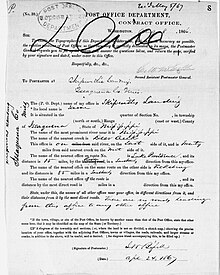

[edit]"General Hampton" (possibly Wade Hampton II) reportedly owned huge tracts of land in the vicinity of Skipwith's Landing and once had 200 slaves moved there.[5] Circa 1866, a witness at a U.S. Congressional hearing described Skipwith's Landing as being among the most sparsely populated sections of the state with no village or town in proximity.[6] Circa 1867, there were no roads leading to or from Skipwith's Landing; the only access was by the river.[3] For a time there was a cut made by the river that was known as Skipwith's Chute.[7] Another related placename was Skipwith Crevasse.[8] There was a U.S. post office at Skipwith's in 1870.[9]

Skipwith's Landing was used as an anchorage and crewing site for gunboats during the American Civil War.[10][11] The U.S. Navy also kept coal barges and eventually built a repair and carpentry shop there.[12] Skipwith's Landing was opposite Island 92.[8] The Sam Gaty sank nearby in 1863.[8]

Steamboats of the era were fueled by wood, and burned something like 70 cords of wood per day.[13] Therefore, there were "hundreds of wood yards" along the Mississippi during the steamboat era, "one every several miles on the busiest sections of the river."[14] According to The Half Has Never Been Told, the cotton empire of the Mississippi River valley opened a "new frontier" along the river above Vicksburg in the late 1840s, so Skipwith's Landing may have been established in the late 1840s or in the 1850s.[15] In addition to exporting cotton, the landing would have been used to import enslaved people who grew that cotton and made up roughly 80 percent of the percent of the antebellum population of the area.[15]

After the war, Skipwith Landing's major municipal advantage was that it had a store that sold liquor.[16] Then Duncansby Landing opened 100 yards above Skipwith's Landing and became the dominant settlement in the vicinity, and by 1887, Duncansby reportedly had a population of about 100 people and Skipwith had faded off the map.[16]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ United States War Department (1898). The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. U.S. Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-918678-07-2.

- ^ State of Mississippi (1857). Laws of the State of Mississippi. p. 96.

- ^ a b "Skipwith's Landing", Record Group 28: M1126 - Post Office Department Reports of Site Locations, 1837-1950. Roll 307 Mississippi: Hinds - Issaquena, 68464705

- ^ Main, E. M. (1908). The story of the marches, battles, and incidents of the Third United States Colored Cavalry: a fighting regiment in the War of the Rebellion, 1861-5. Louisville, Ky.: Globe Printing Co. p. 270. hdl:2027/loc.ark:/13960/t5j968p2r. Retrieved September 17, 2023 – via HathiTrust.

- ^ Bancroft, Frederic (1959). Slave trading in the Old South. Internet Archive. New York, Ungar. pp. 243–244.

- ^ U.S. House of Representatives (1866). House Documents. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ^ U.S. Mississippi River Commission (1884). Reports. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ^ a b c Bragg, Marion (1977). Historic Names and Places on the Lower Mississippi River. [Department of Defense], Department of the Army, Corps of Engineers, Mississippi River Commission.

- ^ U.S. Post Office Department (1870). List of Post Offices and Postmasters in the United States: Revised and Corrected to Sept. 1, 1870. p. 302.

- ^ "Particulars of the Destruction of the Steamer Clara Bell". NYT. August 9, 1864.

- ^ "Sailor Detail - The Civil War". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ^ Jr, Myron J. Smith (November 1, 2021). After Vicksburg: The Civil War on Western Waters, 1863-1865. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-7220-5.

- ^ Nicholls, John Ashton (1862). In Memoriam: A Selection from the Letters of the Late John Ashton Nicholls. Johnson and Rawson, printers. pp. 382–383.

- ^ Johnson, Walter (2013). River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 94. ISBN 9780674074880. LCCN 2012030065. OCLC 827947225. OL 26179618M.

- ^ a b Baptist, Edward E. (2016). The half has never been told: slavery and the making of American capitalism (paperback first published ed.). New York: Basic Books. ebook pp. 1,216–1,218 of 1,737. ISBN 978-0-465-04966-0.

- ^ a b "Issaquena County by W. E. Collins". The Weekly Democrat-Times. Greenville, Mississippi. October 1, 1887. p. 1. Retrieved July 25, 2024.