Shane O'Neill (Irish exile)

Shane O'Neill Seán Ó Néill | |

|---|---|

| 3rd Earl of Tyrone | |

| Coat of arms |  |

| Tenure | 1616–1641 |

| Predecessor | Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone |

| Successor | Hugo Eugenio O'Neill[1] |

| Born | 18 October 1599 Dungannon, Ulster, Ireland |

| Died | 27 January 1641 (aged 41) Catalonia, Spain |

| Noble family | O'Neill dynasty |

| Spouse(s) | Isabel O'Donnell |

| Issue | Hugo Eugenio O'Neill[2] |

| Father | Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone |

| Mother | Catherine Magennis |

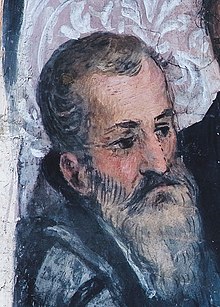

Colonel Shane O'Neill, 3rd Earl of Tyrone[3][a] (Irish: Seán Ó Néill; Spanish: Juan O'Neill; 18 October 1599 – 27 January 1641) was an Irish-born nobleman, member of the Spanish nobility and soldier in the Spanish army who primarily lived and served in Continental Europe.

A son of Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone, Shane and his family left Ireland in 1607 due to hostility from the English government. Shane grew up in the Spanish Netherlands and eventually moved to Spain to serve in the army. Though James I of England had attainted his father's title in 1613,[3][8] the Spanish court granted Shane the equivalent Spanish title El Conde de Tyrone.[3]

Family background

[edit]Shane O'Neill was born in Dungannon, Ireland[3] on 18 October 1599.[7][9][10] His father was Irish lord Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone,[3][11] Chief of the Name of the O'Neill clan, Tír Eoghain's ruling Gaelic Irish noble family.[12][13] His mother was Tyrone's fourth wife Catherine Magennis,[9][3][11][10] daughter of Sir Hugh Magennis, Baron of Iveagh.[14][15]

Shane had two full-brothers, Brian and Conn.[11][9] Shane was the eldest of Tyrone and Catherine's sons;[3] Brian was born c. 1604[9] and Conn was born c. 1602.[9][16][17] Conversely the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland claimed that Shane was Hugh's youngest son.[18]

Early life

[edit]

In September 1607, Shane left Ireland with his parents during the Flight of the Earls.[19][20] He was considered too young to accompany his father on the journey to Rome and was left in Flanders in the care of his elder half-brother Henry.[21][22] He was educated by Franciscans in St Anthony's College, Leuven,[23][24] in the company of his brother Brian and fellow nobles Hugh Albert O'Donnell (son of Rory O'Donnell) and Hugh O'Donnell (son of Cathbarr O'Donnell).[24]

A few years later, two of Shane's older half-brothers died in quick succession. Hugh died in Rome in 1609; Henry died in Aranda in 1610.[25][26] Henry had been a colonel of an Irish regiment in Archduke Albert VII's army, and his death left a vacant colonelcy. Henry and Archbishop of Tuam Florence Conry feared that the English would try to fill the vacancy with a colonel sympathetic to the English government.[10] Two weeks after Henry's death, Conry wrote to Philip III, urging him to immediately appoint Eugenio O'Neill, a cousin, to the colonelcy. Tyrone instead requested that Shane be appointed to the colonelcy. Philip III granted this request.[10][9]

In 1613, Shane went to the court at Brussels as a page to Isabella Clara Eugenia. His father continued to compel the Spanish government to grant Shane special privileges which could be of use to his exiled countrymen. In 1614 Shane's father sent another petition to Philip III asking him to make Shane a Knight of the Military Order of Santiago. Philip III refused this, stating that other individuals of merit must be attended to first, but that he would consider anything that could be done for Shane.[27]

Shane succeeded as Earl of Tyrone upon his father's death[3] in Rome on 20 July 1616.[13] Though James I of England had attainted his father's title in 1613,[3][8] the Spanish court granted Shane the equivalent Spanish title El Conde de Tyrone.[3]

Shane became estranged from his mother due to arguments over the late Earl's will. They disputed over their shares of the late earl's pension as well as the maintenance of his dependents.[28][29] Hugh's unhappy retainers asked the late earl's secretary to inform Shane that his mother was refusing to give them the money bequeathed to them. The claimants asked for Shane's support and even suggested that Catherine be "enclosed in a convent of nuns". They cautioned Shane to send someone to Rome, to deposit his late father's money and valuable in a bank before his mother could.[30]

On 16 August 1617,[31][32] Shane's brother Brian was found hanged in his room in Brussels under suspicious circumstances,[19][29] possibly killed by an English assassin.[9][33] When Catherine died in March 1619, Shane was said to be greatly saddened.[34]

Military service

[edit]Once old enough, Shane took up service to the Spanish crown in one of the Irish regiments in Flanders. While there he, like his other O'Neill cousins, constantly planned the return of his father and the restoration of the Gaelic order in Ulster. He became titular colonel of the Regiment of Tyrone on the death of his half-brother Henry at the request of his father.[23][35] (O'Neill's cousin Owen Roe O'Neill, although he failed in a bid to assume command of the regiment, later served as second-in-command and acting commander of the regiment until Shane O'Neill was old enough to assume the role).[36] Shane started using the title El conde de Tyrone around the time he succeeded his half-brother Henry in the command of the Irish regiment in Flanders.[9] In 1613 he was at court in Brussels as the page of the Infanta Isabella.[23] After his father died in Rome in 1616, Shane assumed the title of Earl of Tyrone. His ascent was recognized by both the Pope Urban VIII and the Infanta Isabella of Spain, the Royal Governor of the Spanish Netherlands. His title, Conde, or Count, was recognised in Spain but no longer in England or Ireland.[23] The title had been granted to his great-grandfather Conn Bacach O'Neill, 1st Earl of Tyrone by Henry VIII of England, and confirmed to his father Hugh by Elizabeth I; it was forfeit by an act of attainder passed by the Irish Parliament in 1608.

He eventually held the rank of Colonel.[34]

A 1625 proposal to the Infanta by Irish expatriates in the Spanish Netherlands, notably Archbishop Conry and O'Neill's cousin Owen Roe O'Neill, for an invasion of Ireland by Spanish forces was rejected; the Archbishop and Owen Roe O'Neill made their way to Madrid to present the plan to the King of Spain, Philip IV of Spain, arriving in 1627. The proposal called for a landing at Killybegs, with the city of Derry to be taken to provide a defensible port. The proposal also called for the Spanish forces to be led by Shane O'Neill and Hugh O'Donnell, son of Rory O'Donnell, 1st Earl of Tyrconnell who had accompanied his father to Flanders during the Flight of the Earls. To ease tensions between the two families, it was proposed that both were to be appointed as generals of the invasion force and would be considered equals; O'Donnell would be in command of a second Irish regiment created from the existing regiment and the two new regiments would be supplemented with men drawn from other Spanish forces in the Netherlands.[37]

Although a fleet of 11 ships was assembled at Dunkirk, with the fleet anticipated to sail in September 1627, disagreements remained over the composition and leadership of the invasion force. The Infanta in Brussels, wishing to reduce the repercussions to Spain in the event of failure, wanted to reduce the number of Walloons and wished for Shane O'Neill to be in sole command. while Madrid favoured O'Donnell. The final plan proposed in December 1627 called for the establishment of new Irish parliament and that it would be known that O'Neill and O'Donnell were not undertaking the invasion for personal gain, but for the establishment of a "Kingdom and Republic of Ireland". In the end, the plan was abandoned by the King of Spain.[37]

O'Neill was considered as a threat to English supremacy in Ireland. A 1627 letter from the Lord Deputy of Ireland, Viscount Falkland, claimed evidence existed to the effect that the King of Spain planned to send O'Neill to Ireland at the head of a Spanish army to claim the throne of Ulster for O'Neill himself, and to be proclaimed as governor of Ireland on behalf of the Spanish monarch. (Falkland also claimed that a story was circulating among the Irish that O'Neill had already received a crown of gold, which he kept on a table beside his bed).[21]

Shane O'Neill approached Philip IV with another proposal for an invasion in 1630; this proposal was rebuffed. During his time in Madrid, O'Neill was made a Knight of Calatrava and a member of the Spanish Supreme Council of War.[37] In 1639, another request by O'Neill to the Spanish king Philip IV that he be allowed lead a Spanish army to Ireland was rejected.[38]

O'Neill used his influence with the Pope to have his former tutor Aodh Mac Cathmhaoil (anglicised as Hugh MacCaghwell) installed as Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland in 1626.[21] In 1630 he founded the College of San Pedro, y San Pablo y San Patricio in Alcala; it closed after his death.[39]

In 1638, the Irish regiments commanded by O'Neill and O'Donnell were transferred from the Army of Flanders to Spain to bolster forces there in the face of an expected French invasion. These regiments were involved in the Spanish attempt to put down the Catalan Revolt.[40] Shane died in January 1641, leading his regiment during the Battle of Montjuïc near Barcelona, dying from a musket-ball wound to his chest near the town of Castelldefels.[41][32] His regiment suffered catastrophic losses in the engagement.[40]

Henry O'Neill died in Catalonia[32] on 27 January 1641.[7][9][18] He left behind a son, Hugh/Hugo, 9 years of age.[9]

In 1641, Rory O'Moore, unaware of O'Neill's death, sought his assistance for the planned rebellion of 1641.[42]

Family

[edit]While in Madrid after 1630, he met Isabel O'Donnell and they had a child out of wedlock, Hugh Eugenio O’Neill, who was later legitimised by the King. (One suggestion to allay tensions between the O'Neills and O'Donnells during the planning of the aborted 1627 invasion was the marriage of Shane O'Neill to Mary Stuart O'Donnell, the daughter of Hugh Roe O'Donnell, sister of O'Neill's rival Hugh and cousin of Isabel).[37]

The family tradition of the O'Neills of Martinique is that Shane also had a legitimate son Patrick, and that Shane and Patrick both fought with Owen Roe O'Neill in 1642; according to this tradition, Patrick married and settled in Ireland. The Martinique family claims descent from his son Henry, who emigrated at some time during the reign of James II.

Owen Roe O'Neill, the famous Irish General of the 1600s, was asked whether he, upon the death of Shane O'Neill, was the Earl of Tyrone. He denied it, saying that the true Earl was Constantino O'Neill, then in Spain. Don Constantino or Conn O'Neill was cousin to both Shane and Owen O'Neill through both sides of his family. His great-grandfather was Conn McShane O'Neill, a son of the famous Prince Shane O'Neill of Ulster, through to his father Art McShane. His mother Mary, was the daughter of Art MacBaron O'Neill, the brother of Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone. Don Constantino lived in Ireland, but made his way to Spain to claim the title upon the death of his cousin in 1680. Unfortunately for Constantino, the King, thinking there was no heir, gave the title and command of the Irish regiment to the son of an illegitimate O'Neill cousin. Constantino went back to Ireland and was an active politician and military officer in the Williamite War as a supporter of King James II.

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Walsh 1974, pp. 321–325. If Shane died, the Earldom was to pass first to his cousin Conn, then to his illegitimate cousins, the sons of Art MacBaron, then to the descendant of Shane the Proud who should be nearest in blood.

- ^ Walsh 1974, p. 323.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Walsh 1974, p. 320.

- ^ McNeill 1911, p. 109.

- ^ Maginn, Christopher (January 2008) [2004]. "O'Neill, Shane [Sean O'Neill] (c. 1530–1567)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- ^ O'Byrne, Emmett (October 2009). "O'Neill (Ó Néill), Brian". Dictionary of Irish Biography. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ a b c Burke, John, ed. (2003). Burke's Peerage. Vol. 2 (107 ed.). p. 3006.

- ^ a b McNeill 1911, p. 110.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Walsh 1930, p. 31.

- ^ a b c d Walsh 1957, p. 10.

- ^ a b c Casway 2016, p. 73.

- ^ Morgan, Hiram (October 2005). "Gaelic lordship and Tudor conquest: Tír Eoghain, 1541–1603". History Ireland. 13 (5). Archived from the original on 10 June 2024.

- ^ a b Morgan, Hiram (September 2014). "O'Neill, Hugh". Dictionary of Irish Biography. doi:10.3318/dib.006962.v1. Archived from the original on 26 September 2023. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ Casway 2016, p. 69.

- ^ Walsh 1930, p. 20.

- ^ Casway 2016, p. 74.

- ^ Casway 2003, p. 61.

- ^ a b Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland 1867, p. 459.

- ^ a b McGurk, John (August 2007). "The Flight of the Earls: escape or strategic regrouping?". History Ireland. 15 (4). Archived from the original on 18 April 2024.

- ^ Casway 2016.

- ^ a b c Meehan 1868, pp. 458–461.

- ^ Casway 2016, p. 75.

- ^ a b c d Walsh 1974.

- ^ a b Casway 2003, p. 66.

- ^ Walsh 1957, p. 9.

- ^ Casway 2016, pp. 70–72.

- ^ Walsh 1957, p. 11.

- ^ Casway 2003, pp. 62–63.

- ^ a b Casway 2016, p. 76.

- ^ Casway 2003, p. 63.

- ^ Walsh 1930, p. 9.

- ^ a b c Dunlop 1895, p. 196.

- ^ O'Hart, John (1892). "O'Neill (No.2) Irish genealogy". Irish Pedigrees; or the Origin and Stem of the Irish Nation. 1 (5 ed.). Retrieved 21 September 2024.

- ^ a b Casway 2003, p. 64.

- ^ Walsh 1957.

- ^ Jerrold I. Casway (1969). "Owen Roe O'Neill's Return to Ireland in 1642: The Diplomatic Background". Studia Hibernica (9). St. Patrick's College: 48–64. JSTOR 20495923.

- ^ a b c d Tomás Ó Fiaich (1971). Pádraig Ó Fiannachta (ed.). Léachtaí Cholm Cille II Stair (PDF). An Sagart.

- ^ Hillgarth, J. N (2000). The mirror of Spain, 1500–1700: the formation of a myth. University of Michigan Press. p. 432. ISBN 978-0-472-11092-6.

- ^ Patricia O'Connell. The Irish College at Alcalá de Henares: 1649–1785. p. 27. 1997

- ^ a b Moisés Enrique Rodríguez (31 August 2007). "The Spanish Habsburgs and their Irish Soldiers (1587–1700)". Society for Irish Latin American Studies. Retrieved 24 June 2011.

- ^ Manel Güell (1998). "Expatriació Militar I Mercenaris Als Exercits De Felip IV". Pedralbes (in Catalan). Vol. 18. Universidad de Barcelona. Departament d'Història Moderna. p. 78. ISSN 0211-9587. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- ^ Perceval-Maxwell, M. (1994). The outbreak of the Irish Rebellion of 1641. McGill-Queen's Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-1157-6.

Sources

[edit]- Casway, Jerrold (2003). "Heroines or Victims? The Women of the Flight of the Earls". New Hibernia Review / Iris Éireannach Nua. 7 (1): 56–74. ISSN 1092-3977. JSTOR 20557855.

- Casway, Jerrold (2016). "Catherine Magennis and the Wives of Hugh O'Neill". Seanchas Ardmhacha: Journal of the Armagh Diocesan Historical Society. 26 (1): 69–79. ISSN 0488-0196. JSTOR 48568219.

- Meehan, Charles Patrick (1868). The fate and fortunes of Hugh O'Neill, earl of Tyrone, and Rory O'Donel, earl of Tyrconnel; their flight from Ireland, their vicissitudes abroad, and their death in exile. University of California Libraries. Dublin, J. Duffy.

- Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland (1867). "PROCEEDINGS AND PAPERS". Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. 5: 459.

- Walsh, Micheline (1974). "The Will of John O'Neill, Third Earl of Tyrone". Seanchas Ardmhacha: Journal of the Armagh Diocesan Historical Society. 7 (2): 320–325. doi:10.2307/29740847. JSTOR 29740847.

- Walsh, Micheline (April 1957). The O'Neills in Spain (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 July 2024.

- Walsh, Paul (1930). Walsh, Paul (ed.). The Will and Family of Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone [with an Appendix of Genealogies] (PDF). Dublin: Sign of the Three Candles. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 May 2024.

- O'Neill, the Ancient and Royal Family

- McCavitt, John (2002). The Flight of the Earls. Gill & MacMillan.

Attribution

[edit]- Dunlop, Robert (1895). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 42. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 188–196.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: McNeill, Ronald John (1911). "O'Neill". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 107–111.